You are here

Building a Mosaic: The Evolution of Canada’s Approach to Immigrant Integration

Immigrants celebrate Canada Day by being sworn in as Canadian citizens at a ceremony in Edmonton. (Photo: Chris Schwarz/Government of Alberta)

Long one of the world’s most welcoming immigrant destinations, Canada is often held up as a model for how to craft sound immigration policy in a multicultural democracy, with more than one of every five Canadian residents foreign born. In 2016, it was home to 7.5 million immigrants, among the largest foreign-born populations in the world. Though economic considerations have largely driven Canada’s policy preference for highly skilled immigrant workers, the country has also recently become a leader in refugee resettlement. Nearly 47,000 refugees were resettled in 2016—the highest level in Canadian history.

The Canadian approach to immigration, settlement, citizenship, and multiculturalism did not happen by accident. Geography has played a role: Three oceans (one frozen most of the year) and a developed country to the south act as a buffer from large-scale uncontrolled migration. Furthermore, Canadian history—a complex and imperfect process of accommodation, entailing acceptance and compromise between indigenous peoples and French and British settlers—made the country more multinational in character from its start than a traditional nation-state.

The success story of Canadian immigration has its roots in this context. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, as the various English versus French “Canada crises” played out alongside efforts to assimilate indigenous peoples, the understanding that one group or culture could never completely dominate endured. The ongoing creative tension between groups produced a culture of accommodation, central to Canada’s ability to absorb and integrate newcomers. Further, the widely held perception among Canadians that immigrants are an economic boon and cultural asset to the country has made public opinion on the subject generally resilient, even as sharp backlashes have unfolded in the United States and Europe.

Over the years, Canada’s approach to immigration and integration has evolved to reflect shifting needs and considerations, as well as the increasing diversity in the foreign-born population. This article explores this approach, the unique result of a convergence of historical, geographical, political, and cultural factors. Following the selection process, which itself plays a key integration role, Canadian immigrant integration benefits from three sets of policies with distinct functions: helping immigrants settle through language and workforce training and other services, encouraging them to become citizens, and supporting their full participation in society through multiculturalism and related policies.

Canada: Built on Immigration

Canada has long been a country of immigrants, largely selected for their ability to contribute to economic development. Though the source countries have evolved, the focus on employment-based immigration has remained, while also allowing for family reunification and refugee admissions.

Overall, given Canada’s geography (and the Safe Third-Country Agreement with the United States, which bars asylum seekers from filing duplicate claims in both countries), its immigration is heavily managed. The recent trickle of unauthorized land crossings from the United States is tiny in relation to the much larger scale of irregular migration and asylum-seeker flows to Europe and the United States, and is also small compared to Canada’s total annual intake of refugees. However, these spontaneous arrivals have understandably provoked some concerns about immigration management.

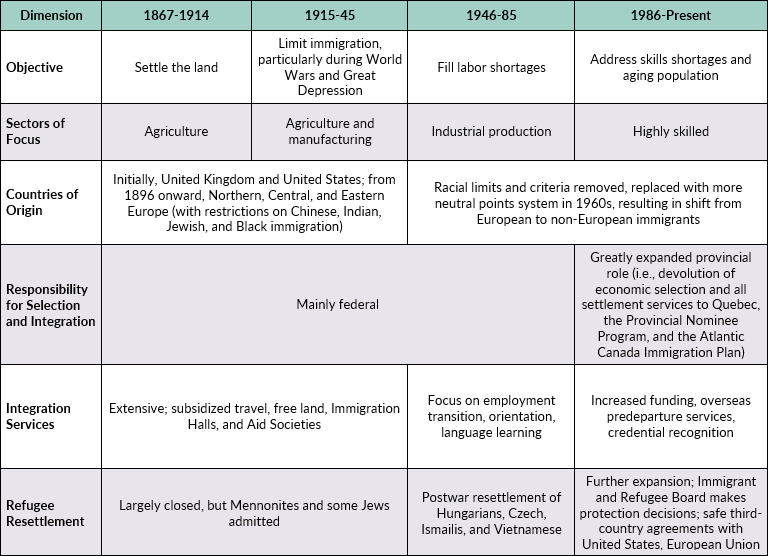

Competing priorities have driven shifts in Canadian immigration policy over the decades (see Table 1). Policies have generally moved toward greater skills-based immigration, diversification and removal of racial restrictions, expansion of the role of provincial governments, increased focus on integration services, and greater refugee resettlement.

Table 1. Immigration to Canada, 1867 to Present

Sources: Information based on Valerie Knowles, Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy 1540-2015 (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2016); and Ninette Kelley and Michael Trebilcock, The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013).

In the 1960s, Canada made dramatic changes liberalizing immigration. It did away with race-based selection criteria in 1962, and subsequently established the more neutral points system in 1967 to assess potential immigrants based on their ability to integrate quickly into the workforce (e.g., language, education, experience, skills, and job offers). These changes paved the way for Canada’s current diversity, with the entry of greater numbers of non-European immigrants. Over the past decade, the Philippines, India, and China have been the top three source countries for new arrivals.

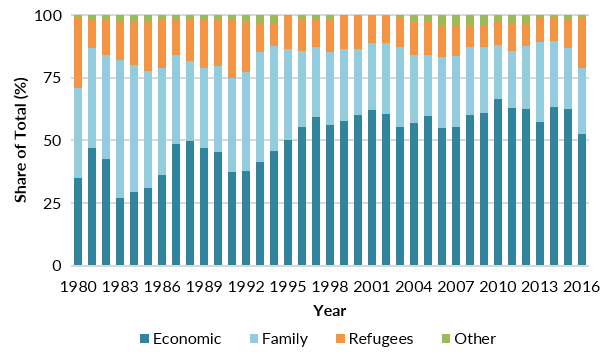

In addition to the changes in origins, the composition of immigrant arrivals based on the three classes—employment-based immigration, family reunification, and refugee resettlement—has evolved over the past 35 years (see Figure 1). More recently, immigrants admitted under economic preferences have consistently accounted for half or more of newly arrived immigrants. Taken together, these shifts have had important implications for Canadian integration policy and outcomes.

Figure 1. Permanent Resident Arrivals by Category, 1980-2016

Source: Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), “Admissions of Permanent Residents by Immigration Category,” accessed October 20, 2017, available online.

An Evolving Approach to Integration

During the 20th century, as immigration to Canada grew and diversified, the Canadian government worked to refine its approach to integration. The framework first developed in the context of mainly white, primarily Christian immigration. In one of the earliest enunciations, the 1959 Canada Year Book defined integration as distinct from assimilation (i.e., as entailing the retention of cultural identity), voluntary in nature, and the responsibility of the host society. It set the stage for a different approach to integration, compared to other immigration-based societies.

In 1969, the Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism further clarified the distinction between integration and assimilation, noting that “man is a thinking and sensitive being; severing him from his roots could destroy an aspect of his personality and deprive society of some of the values he can bring to it.”

Since then, a number of major policies have put this approach to integration into practice. Canada’s shift to prioritize employment-based immigration, with a points system favoring skilled workers who can speak English or French and integrate more easily, ensures integration considerations are built in from the earliest stage, at selection. The government has frequently adjusted the points system to further improve labor market integration, most recently with the 2015 introduction of the Express Entry system to fast-track those skilled workers deemed most likely to integrate successfully. Upon arrival, policies and programs targeting settlement, citizenship, and multiculturalism further facilitate integration.

Settlement Policies

Central to Canada’s approach to integration is the range of services provided to assist immigrants in settling and establishing themselves in their new country.

About 70 percent of the Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) budget in 2016-17 was dedicated to settlement services, amounting to CA $1.2 billion. Of this sum, $345 million was allocated directly to Quebec, given it is responsible for administering services to newcomers. Of the remaining provinces, Ontario accounted for the largest share of federal funding for settlement services, roughly 55 percent, followed by British Columbia with 17 percent and Alberta with 15 percent. Language classes receive the largest proportion of funding, while employment and orientation services are also available to new arrivals.

About 400,000 individuals accessed these services in 2015-16 (including about 27,000 immigrants who participated in French classes in Quebec). Services are available free of charge for immigrants and refugees for as long as they meet basic eligibility requirements. Temporary workers and students, meanwhile, are not eligible.

Citizenship Policies

Underlying Canada’s immigrant selection is the assumption that most permanent immigrants will become citizens and integrate into the political, economic, and social fabric of Canadian life. As such, naturalization policy functions as a tool to support integration. Canada’s approach emphasizes accessibility, while balancing requirements for length of residency and basic integration measures, which have evolved over time.

Prior to the 1947 Citizenship Act, Canadian residents were either British subjects or aliens, with naturalization policies similar to those elsewhere in the British empire. This law marked the first articulation of the basic tenets of Canadian citizenship policy, including birthright citizenship, language and knowledge requirements, and required length of residency.

As with most other countries in the Western Hemisphere, birthright citizenship (jus soli) has long been a cornerstone of Canadian policy, in contrast to societies where ancestry and bloodline (jus sanguinis) determine an individual’s citizenship at birth. Immigration-based countries also generally have shorter required residency periods than other countries; Canada’s have varied between two and five years as governments oscillate between more facilitative and more restrictive approaches.

Language plays a critical role in integration, and fluency requirements for naturalization can vary depending on whether the country views citizenship as an endpoint of integration or a step in the process. Canada favors the latter approach, requiring only “adequate knowledge" of English or French, defined as basic fluency. In addition, since the 1947 Citizenship Act, factual knowledge has been required to obtain Canadian citizenship, although the content and modalities of assessment have varied.

The 1977 Citizenship Act made a number of changes liberalizing naturalization policy, including formally allowing dual nationality, dropping the “intent to reside” clause, and eliminating revocation of citizenship for terrorism or treason, given that the Canadian criminal justice system was deemed a more appropriate form of punishment. Several of these tweaks have been undone and redone by subsequent administrations; for example, a Conservative administration resurrected the terrorism revocation provision in the 2014 Citizenship Act, only to have it repealed by a Liberal administration in 2017.

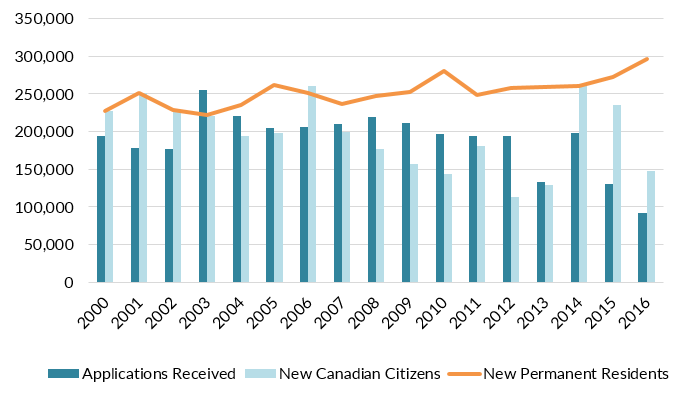

Since 2000, as the number of new permanent residents steadily increased, naturalizations have fluctuated (see Figure 2). Following changes in 2014-15 designed to make citizenship “harder to get and easier to lose,” including a quintupling of fees from $100 to $530, the number of applications fell from nearly 200,000 in 2014 to 92,000 in 2016. The change has disproportionately affected visible minorities, particularly family- and refugee-class immigrants.

Figure 2. New Canadian Citizens and Overall Applications by Year, 2000-16

Sources: Citizenship data from IRCC, “Citizenship – Quarterly IRCC Updates,” accessed October 20, 2017, available online; and permanent resident data from IRCC, “Admissions of Permanent Residents by Immigration Category.”

Multiculturalism Policies

Multiculturalism, the recognition of cultural and ethnic identities as a means to facilitate integration, is a key feature of Canadian immigration policy. A Liberal government formally articulated it for the first time in the Multiculturalism Policy of 1971, and a Conservative government subsequently codified it in the 1988 Multiculturalism Act.

The Multiculturalism Policy was a response to earlier integration thinking and to political pressure for official recognition by Ukrainian Canadians and similar groups. Thus, multiculturalism emerged largely in the context of Caucasian and Christian ethnic groups, who were more readily accepted by the host society than the more diverse groups that would follow. Its main objectives were to:

- Promote the recognition, retention, and fostering of identities to facilitate integration;

- Help immigrants and minorities overcome barriers to participation to ensure that all can contribute to society;

- Promote exchanges between minorities and the broader local community to reduce the risk of segregation; and

- Facilitate language acquisition to support participation.

Subsequently, the Multiculturalism Act required the government to provide an annual report on its efforts to implement multiculturalism.

The policy and law were more aspirational than prescriptive, leaving governments relatively free to adjust the focus as appropriate to the times. The Canadian Constitution’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms, enacted in 1982, and the Employment Equity Act of 1986 provided a more prescriptive framework for implementation.

The program included a small grant initiative for organizations in support of these objectives. In addition, it acknowledged historical immigration restrictions (e.g., against Chinese and Indians) and war-time internment (e.g., of Ukrainians and Japanese) by providing funding to community organizations, to recognize these injustices and improve broader public knowledge of them.

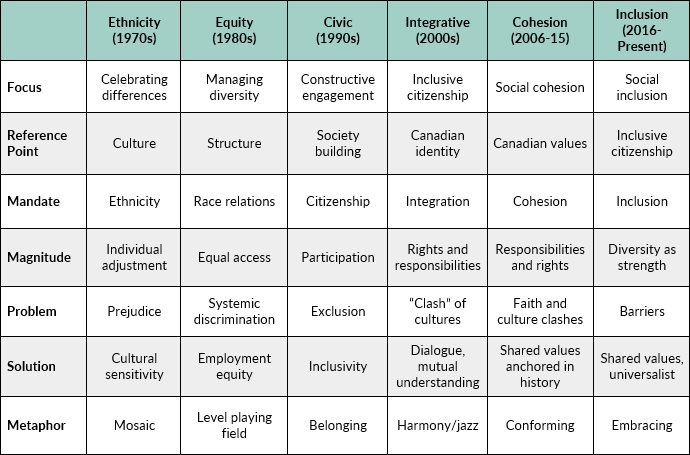

In practice, multiculturalism has evolved over time (see Table 2).

Table 2. The Evolution of Canadian Multiculturalism by Era

Source: Adapted from Augie Fleras and Jean Lock Kunz, Media and Minorities: Representing Diversity in a Multicultural Canada (Toronto: Thompson Education Publishing, 2001).

The initial focus of multiculturalism was to recognize the cultural contributions of various ethnic groups by celebrating difference and diversity. While activities and funding emphasized ethnic group identities, the policy focus was on how the host society could reduce prejudice and discrimination through greater cultural sensitivity.

Following the Charter in 1982, the emphasis shifted to managing diversity and creating a level playing field for all by addressing structural issues. The government implemented policies to accommodate diversity and address systemic discrimination. For example, the Employment Equity Act aimed to increase workforce participation of women, members of indigenous groups, persons with disabilities, and racial and ethnic minorities, with strong reporting requirements for the federal public service and federally-regulated sectors (e.g., banking, communications, and transportation). This approach has been largely successful. Further, a new program provided funding to organizations that wished to bring equality challenges before the courts.

In the 1990s, the focus broadened to include civic engagement, society building, and shared citizenship. Policymakers aimed to increase participation in all aspects of society as a way to reduce actual or potential exclusion. The previous emphasis on removing economic barriers was expanded to inclusivity, with the metaphor shifting in turn to one of belonging.

Following 9/11, policymakers began to view integration through a security lens, and linking inclusive citizenship to Canadian identity became a strategy to reduce the threat of extremism. Policy emphasized the responsibilities of individuals in the integration process. To address the “clash of cultures” discourse, policymakers promoted greater dialogue to foster mutual understanding. The metaphor of harmony reflected Canada’s common legal and constitutional framework (responsibilities), while jazz symbolized the ad hoc improvisation of accommodation requests (rights, primarily encompassing religious requests such as time off for holidays, space for prayer at work or school, and allowance for kosher or halal food).

When Prime Minister Stephen Harper took office in 2006, his Conservative government’s skepticism of multiculturalism and preference for the term “pluralism” resulted in a redefinition toward more prescriptive integration objectives. Responsibilities took precedence over rights. Faith and culture clashes (e.g., radicalized Canadians, accommodation issues) would be addressed by emphasizing shared values, anchored in Canadian history, as exemplified in the Discover Canada citizenship guide.

The 2015 election of Liberal Party leader Justin Trudeau brought the introduction of a government-wide diversity and inclusion agenda that aimed at mainstreaming and embracing multiculturalism. Political appointments grew increasingly diverse, for example, with respect to Cabinet members (e.g., Ministers of Defense and Innovation, and Science and Economic Development), senators, and judges. The Trudeau administration has portrayed diversity as a Canadian strength, with shared, universalist values crucial to overcoming barriers to inclusion.

Ongoing and Emerging Challenges

The Canadian model of integration, based on coherent immigration selection, settlement, citizenship, and multiculturalism policies, has been largely successful in terms of integrating newcomers to Canada. While the native born remain better off economically than immigrants, this gap decreases over time and generations. Overall, a higher share of immigrants and their children are university-educated compared to native-born Canadians, and members of the second generation with university degrees have similar median incomes to their peers with native-born parents. The largest public and private employers in Canada are generally representative of the populations they serve. Similarly, federal political representation of immigrants and their children largely reflects the proportion that are Canadian citizens (provincial government representation varies, however).

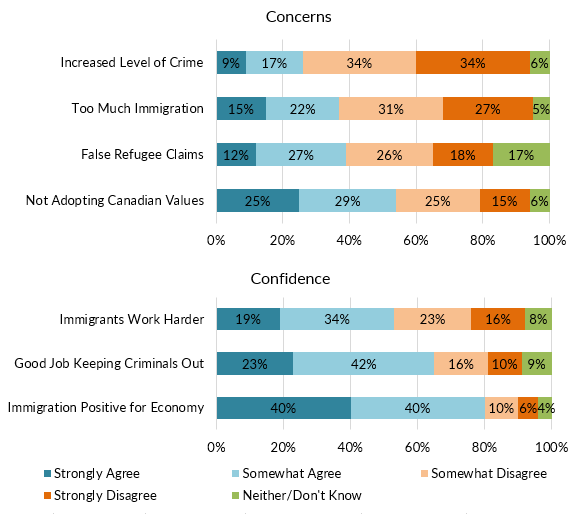

At the same time, the model has maintained host-society support for continued high levels of immigration (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Public Attitudes on Immigration in Canada, 2016

Source: Environics Institute for Survey Research, Canadian Public Opinion About Immigration and Citizenship (Toronto: Environics Institute for Survey Research and Canadian Race Relations Foundation, 2016), available online.

Central to Canada’s success has been its commitment to stay true to the early definitions of integration, while being flexible and open to policy change and refinement. Policymakers and bureaucrats regularly evaluate programs; systematically collect data on integration; analyze commissioned and noncommissioned research; consult with nongovernmental organizations and provinces for their expertise; assess experiences of other countries; and monitor mainstream and ethnic media to identify issues related to integration outcomes. This evidence-based approach forms the basis of advice to the government, with respect to ongoing and emerging issues as well as political priorities.

But Canada’s success depends as much on luck (i.e. geography) and history (i.e. early accommodation), as on conscious policy decisions favoring integration over assimilation. Today’s diversity reflects all three elements, and contributes to the ongoing development of these policies in a more inclusive approach than most other countries. As a result, there are limits to exporting or promoting the Canadian model abroad. Further, ongoing challenges including the gap in economic outcomes, bias and discrimination in hiring practices, impacts on housing and public services, and debates over accommodation issues (i.e., Quebec’s niqab ban) show that Canada’s system is not perfect, and that it may stand to learn from the experiences of other countries.

At the same time, with growing calls and efforts around the world—including just across the border in the United States—to place new restrictions on immigration, policymakers can reduce the influence of foreign discourse on the Canadian political debate by asserting, clearly, the value of multiculturalism in Canada. While multiculturalism may be a dirty word elsewhere (e.g., in Europe), it has been enshrined in the Canadian Constitution and decades of policymaking. Moreover, multiculturalism in Canada is essentially a civic integration approach, one that has worked reasonably well.

Given the international environment, is Canada sufficiently resilient to withstand what appears to be at least a short-term trend toward anti-immigrant sentiment and an at least rhetorical retreat from more inclusive policies? One key element to Canada’s resilience thus far is the confidence of Canadians that their government controls and manages immigration. However, the recent influx of asylum seekers crossing the border from the United States risks undermining that confidence, as Canada begins to experience the kind of spontaneous migration seen elsewhere (albeit on a much smaller scale).

Notwithstanding this risk, Canada’s high levels of overall support for immigration, the widespread belief that immigration leads to economic growth, and the role of large numbers of new Canadian voters in the political system impart a certain degree of protection from populist inclinations, according to researcher Keith Banting. In addition, noted Canadian pollster Michael Adams, in his book Could it Happen Here? Canada in the Age of Trump and Brexit, reviews the range of data available and comes to the same conclusion.

Therefore, while Canadian policymakers and the public at large would do well to remain attentive to signs of populism and anti-immigrant sentiment, Canada is likely to remain strong in the face of threats to social cohesion and inclusion.

This article was adapted from a presentation given by the author at an integration seminar sponsored by the Canadian Embassy and the Centre for Migration Studies at the University of Copenhagen and at the Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity, and Welfare. The author thanks Dan Hiebert and Rob Vineberg for their feedback and suggestions.

Sources

Adams, Michael. 2017. Could it Happen Here? Canada in the Age of Trump and Brexit. Toronto: Simon & Shuster.

Banting, Keith. 2017. Immigration, Multiculturalism and Populist Backlash: Is Canada Exceptional? Presentation given in Ottawa, March 21, 2017.

Environics Institute for Survey Research. 2016. Canadian Public Opinion About Immigration and Citizenship. Toronto: Environics Institute for Survey Research and Canadian Race Relations Foundation. Available online.

Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). 2017. Admissions of Permanent Residents by Immigration Category. Accessed October 20, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. Citizenship – Quarterly IRCC Updates. Accessed October 20, 2017. Available online.

Fleras, Augie and Jean Lock Kunz. 2001. Media and Minorities: Representing Diversity in a Multicultural Canada. Toronto: Thompson Education Publishing.

Kelley, Ninette and Michael Trebilcock. 2013. The Making of the Mosaic: A History of Canadian Immigration Policy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Knowles, Valerie. 2016. Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy 1540-2015. Toronto: Dundurn Press.

Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism. 1970. Volume IV: The Cultural Contribution of the Other Ethnic Groups. Ottawa: Privy Council Office.

Statistics Canada. 1959. Canada Year Book 1959. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

---. 2017. 2016 Census Topic: Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity. Updated October 27, 2017. Available online.