You are here

Climate Migration 101: An Explainer

A woman and child walk in the Somali region of Ethiopia. (Photo: ©UNICEF/Mulugeta Ayene)

Human mobility linked to environmental drivers is not new, but global climate change is triggering more internal and international migration and displacement. Sometimes, the impacts of climate change are fairly direct. For instance, more than 1 million Somalis were displaced by drought in 2022, primarily within Somalia. Other times, impacts are more indirect, as it can be hard to trace how rising global temperatures threaten jobs and livelihoods that compel migration. In rural Honduras and Guatemala, for instance, these impacts have combined and amplified other drivers to prompt people to move to cities, the United States, and other destinations.

Popular discussions tend to start from startingly huge predictions of mass migration, yet the evidence points to a more nuanced reality. Most climate change- and natural disaster-related movement is internal rather than cross-border, and temporary rather than permanent. The likelihood of migration also depends on communities’ vulnerability to the impacts of climate change, which can be mitigated by adaptation measures such as building sea walls or other defenses, as well as individuals’ access to resources to move (including transportation, social networks, and legal pathways). There were 33 million natural disaster-related displacements in 2022, but the biggest displacement situations—from floods in Pakistan to droughts in East Africa—saw people move within their countries, at least at first. And by the end of the year, most disaster-displaced people went back to their homes.

Over time, a bigger issue may be migration prompted by slow, gradual climate change impacts. Hotter temperatures can threaten agricultural livelihoods, sea-level rise can make floods more severe, and desertification can foster conflict over water access, all of which can lead to migration. While rapid-onset disasters typically lead to short-term displacement, people may decide to move permanently or go farther away if events recur repeatedly or cause massive damage. The most vulnerable may end up with the fewest options to move or adapt if persistent climatic threats degrade their ability to respond. Thus, the core challenge is increasingly unpredictable mobility as climate change amplifies existing inequalities and insecurities across the globe.

Mobility is one response to the impacts of climate change, but not an inevitable one, nor is this movement always a negative development. As climate change makes livelihoods harder and disasters more severe, displacement is likely to grow and become more unpredictable, although government action can help individuals remain in place or move in safer, legal ways.

This article provides answers to basic questions about climate change and migration, starting with whether, how, and where climate change triggers migration and displacement. It also takes on questions such as who qualifies as a climate migrant and why there is no “climate refugee” designation.

Special Issue: Climate Change and Migration

This article is part of a special series about climate change and migration.

Click on the bullet points below:

- Is Climate Change a Major Driver of Migration and Displacement?

- Who Is a Climate Migrant?

- From Where Are People Leaving?

- Where Are People Going?

- What Legal Barriers Do Climate Migrants Face?

- What Are the Policy Responses to Climate Displacement?

- Can Migration Be Part of the Solution?

- Will Climate Change Drive Greater Movement?

Is Climate Change a Major Driver of Migration and Displacement?

Climate change is not the main reason why people move, but it is increasingly part of the story. Environmental issues are generally minor factors in people’s migration decisions, typically far behind economic imperatives even in highly climate-affected countries. For instance, in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, just 6 percent of migrant-sending households cited climate- and environment-related reasons for emigration, according to a 2021 report from the World Food Program, Migration Policy Institute, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Similarly, in Central Africa, just 5 percent of migrants reported they moved for environmental reasons, according to a Mixed Migration Centre survey published in 2022. However, when asked whether the environment affected their decision to move, 50 percent of Central African respondents agreed.

This reflects a key challenge in understanding how climate change affects migration. Environmental factors clearly play a role, but not a clear-cut one. In cases where disasters directly trigger displacement, the impacts of climate change may not be clear (some events such as earthquakes are not climate-related, and not all disasters can be attributed to climate change). Government policies are also equally important. Droughts in Syria have been linked to internal displacement that helped enable the Syrian civil war, but government decisions to cut rural subsidies, income security, and access to water resources have been found to be more critical.

Worldwide, natural disasters lead to more displacement than conflict, but this movement tends to be short term. Of the 71.1 million internally displaced people (IDPs) at the end of 2022, just 8.7 million (12 percent) were displaced by disasters. While insecurity and conflict often prevent residents from safely returning to their place of origin, in most cases people go back after natural disasters strike. The world recorded more than 20 million displacements due to natural disasters each year from 2019 to 2022, but most people did not stay displaced for long; fewer than 9 million remained internally displaced at the end of each year.

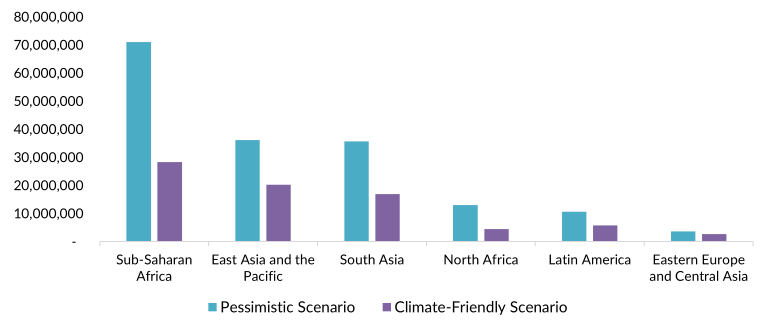

Most disaster-related displacement is short term, but migration related to slow-onset climate change may be more permanent and possibly large-scale. Sea-level rise, land degradation, coastal erosion, extreme temperature, and other gradual impacts of climate change can make entire areas (or in some cases, entire islands) unlivable, threaten the viability of rural livelihoods, and foster competition over resources. These types of changes can also make the repercussions of sudden disasters more severe, for instance when floods and storms layer on top of longer rainy seasons or higher sea levels. In a highly cited prediction, the World Bank’s worst-case estimate is that some 216 million people could move internally by 2050, as water becomes scarcer and agricultural livelihoods are threatened. However, if governments mitigate the pace of climate change and adapt to its impacts, the World Bank predicts this number could drop by as much as 80 percent, to 44 million (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Estimated Internal Climate Migration by 2050, by Select Region and Scenario

Note: Figure shows average number of internal climate migrants predicted under the different scenarios.

Source: Viviane Clement et al, Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration, (Washington, DC: World Bank, 2021), available online.

As a general rule, natural disasters force lots of people to flee, but mostly to nearby neighborhoods from where they quickly return, while slower-onset climate events may over time lead to more migration, including across borders. Yet there are signs this binary is dissolving as sudden and slow-onset events overlap, and as disasters become more frequent and their impacts more severe.

One recent example was the 2022 floods in Pakistan, which displaced an estimated 8 million people and caused approximately U.S. $30 billion in damages. Movement was at first internal, primarily of people evacuating to higher ground. But the floods hit a country already grappling with economic collapse and rampant inflation; just months later, thousands of Pakistanis migrated irregularly to Europe, a movement that captured headlines when a boat carrying approximately 350 Pakistanis and hundreds of other migrants capsized off the coast of Greece. Pakistanis were not among the top ten nationalities arriving irregularly in Europe in 2022, but jumped to fifth in the first half of 2023. Many of these migrants moved primarily because of economic reasons, but these factors were surely amplified by the floods.

Box 1. Problematic Numbers

In climate mobility discussions, misinterpretation of data often inflates fears of mass migration, typically in one of the following ways:

- Assuming all people exposed to climate change, or living in countries highly vulnerable to climate change, will migrate and do so internationally.

- Conflating short-term displacement with permanent migration, ignoring that most disaster-displaced people return to their place of origin.

- Using estimates of all displacement, rather than that linked to climate change and natural disasters.

A thoroughly debunked but nonetheless widely circulated estimate predicts there will be as many as 1.2 billion climate migrants by 2050, a number derived simply by reviewing annual displacement data and assuming all people will remain displaced forever. Other estimates, such as that 80 percent of climate migrants are women, simply circulate with no discernable analysis or methodology. These types of big numbers can be misrepresented for a variety of reasons, including to limit immigration or bring more urgency to the vulnerabilities of climate migrants.

A critical limitation is that it is nearly impossible to estimate how many people will be able to move internationally because of climate change-related impacts. The critical factor in this regard will likely be migration and border policies and how governments choose to manage and respond to environmental displacement, which cannot be captured by scientific projections.

There is no consensus around who counts as a climate migrant, which unlike other types of migrants is not a legally defined category. Since climate change often interacts with other drivers of migration—including economic factors, political unrest, and conflict—a broad swath of people could be said to be moving in part because of environmental degradation or climate impacts. The proliferation of terms about the topic has added to the confusion. Phrases such as “climate refugees” ignore that climate change is not itself grounds for refugee protection; although there are some regional or national migration policies designed for disaster-displaced people, these do not generally apply to all individuals who move because of the indirect impacts of climate change (see below). As such, climate mobility is perhaps the broadest umbrella term for the phenomenon, covering internal and international movement, whether forced or voluntary, temporary or permanent.

The flip side of this issue is that there are many people affected by climate threats who do not move, either by choice or because they are not able to do so. So-called trapped populations who want to flee from climate-affected areas but lack money or other resources are disproportionately marginalized people and often face greater harms staying in dangerous situations than migrants who leave.

From Where Are People Leaving?

The impacts of climate change are being felt all over the world, and thus climate-related migration occurs globally. But the impacts are unequal, and the most severe migration and displacement is often occurring in low- and middle-income countries that have made little historical contribution to warming the planet. This is why displacement is often described as the “human face” of the losses and damages caused by climate change.

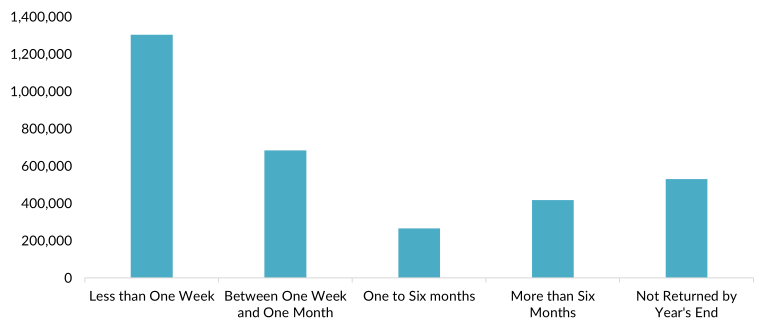

Yet even in high-income countries, climate change is already reshaping migration. According to U.S. Census Bureau data, 3.2 million U.S. adults were displaced or evacuated due to natural disasters in 2022, of whom more than 500,000 had not returned by the beginning of 2023 (see Figure 2). The U.S. government has also begun to assist relocation of entire communities, including Native American villages and neighborhoods highly vulnerable to sea-level rise. Public concerns over future displacement are significant in high-income countries. In a 2019-20 European Investment Bank survey, 24 percent of Europeans (and 41 percent of young Europeans) thought they would have to move because of climate change. In the United States, 30 percent of respondents in a 2022 Forbes Home survey cited climate change as one reason why they might move.

Figure 2. Adults Displaced by Natural Disasters in the United States, by Duration of Displacement, 2022

Notes: Figure shows outcomes for adults who reported being displaced by a natural disaster within the past year; survey was conducted from January 4 to January 16, 2023.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, “Week 53 Household Pulse Survey: January 4 - January 16,” January 25, 2023, available online.

Nonetheless, climate mobility disproportionately happens in lower-income countries, which tend to be more vulnerable to climate change but often contributed minimal historical climate emissions. In 2022, 21 percent of disaster displacements occurred in least developed countries and Small Island Developing States, which collectively made up less than 15 percent of the global population. For instance, that year, Bangladesh and Somalia each recorded over 1 million displacements due to cyclones and droughts, respectively. Models suggest the largest future internal climate migration will occur in sub-Saharan Africa and the Asia-Pacific region, both of which are highly populous and vulnerable to climate change.

As with other types of migration, most people moving amid climate impacts will travel relatively short distances, typically within their country. Climate mobility varies widely, but migrants often go to cities. There is no universal pattern of how a single type of climate event affects displacement—one study by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre found extreme temperatures are associated with increasing displacement in North and West Africa, but not in East or Southern Africa. And within countries, climate change will make some cities attractive destinations—often for people coming from rural regions dependent on agriculture—while others will be sources of out-migration, as people leave neighborhoods vulnerable to flooding and other climate-related threats.

A related challenge is understanding how climate change will affect migrants already at their destinations. Migrants moving for economic opportunity, to flee conflict, to reunite with family, or any other non-climate reason can find themselves affected by climate change. For instance, thousands of Central Americans have moved to Belize in recent decades, often fleeing political instability, and live in informal settlements that become isolated during floods and when dirt roads are wiped away. In places such as Jordan, Syrian refugees have strained an already limited supply of water.

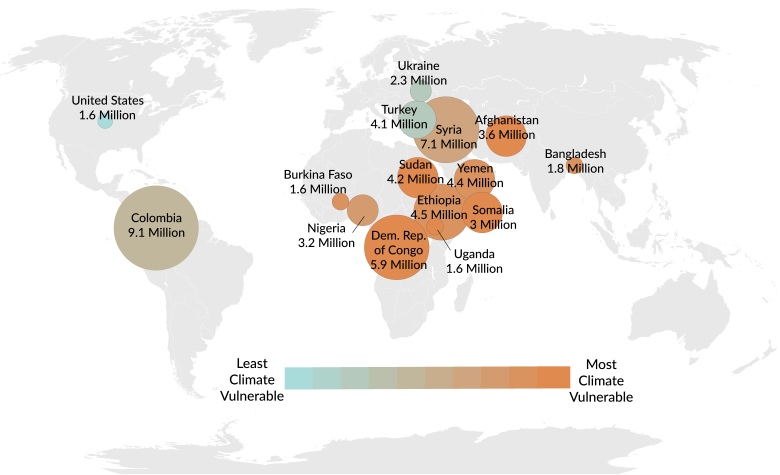

Refugees and others with protection needs are disproportionately hosted by countries highly vulnerable to climate change. For instance, Somalia is the world’s most climate-vulnerable country, according to the Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative’s ranking, and it hosts approximately 3 million humanitarian migrants. Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Sudan, Uganda, and other countries host millions of people primarily fleeing war and violence, and all are among the most vulnerable to climate change (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Top Humanitarian Migrant-Hosting Countries, by Population of Concern and Climate Vulnerability Level, 2021

Note: Population in figure refers to refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced people (IDPs), stateless people, and others identified by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to be in need of international protection or to be of concern.

Sources: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) artist rendering based on UNHCR, “Refugee Data Finder,” accessed November 15, 2023, available online; Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN), “Vulnerability,” accessed November 4, 2023, available online.

What Legal Barriers to Movement Do Climate Migrants Face?

There is no international legal category for climate refugees, and climate change is not grounds for international protection. The 1951 Refugee Convention conditions refugee status on fleeing persecution on one of five grounds—race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group—and makes no mention of environmental factors. Theoretically nations could reopen the convention to modify the definition, but the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and others fear doing so would more likely result in weaker protections for currently recognized refugees rather than expanded grounds for climate refugees, since there is limited political appetite in many countries to expand asylum and resettlement generally.

There are also logistical challenges with any plan to accommodate climate migrants in particular. For one, it is nearly impossible to determine who precisely would qualify, given the impacts can be hard to disentangle from other migration drivers and all communities feel some effects of climate change. People fleeing disasters may be a clear case of climate displacement, but they also can number hundreds of thousands at a time and be displaced with little warning.

What Are the Policy Responses to Climate Displacement?

Despite these challenges, there have been a series of initiatives since the mid-2010s to try and create pathways for people displaced by natural disasters and climate change, with mixed success.

Most famously, in 2017 New Zealand announced its intentions to experiment with a “climate refugee” visa scheme for around 100 Pacific Islanders each year. The policy failed, primarily because Pacific Islanders did not want to take advantage of it; individuals chose to stay in place rather than participate in a visa program they saw as admitting their ancestral and spiritual homes would succumb to sea-level rise. In November 2023, Australia and Tuvalu announced plans for a bilateral treaty to allow 280 Tuvaluans (more than 2 percent of the national population) to migrate to Australia each year, in addition to Canberra providing funding for Tuvaluan climate adaptation and having significant control over Tuvalu’s international security agreements. This effort, while not yet implemented, could allow a small but meaningful number of people to move specifically because their island faces sea-level rise, which would be unprecedented policy.

Some countries have tweaked existing policies, such as by integrating climate considerations into refugee status determinations (for instance by looking for cases of minority groups facing persecution by being excluded from scarce water supplies). In Africa and Latin America, the Organization for African Unity (OAU) Convention and Cartagena Declaration provide a more expansive refugee definition that includes “people fleeing serious disturbances to public order,” which some have taken to include environmental degradation and climate events. In 2010 and 2011, Kenya and Ethiopia gave Somalis fleeing famine and drought protection under the OAU Convention definition.

Other legal tools focus primarily on disasters:

- Free movement protocols: In Eastern Africa, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development’s (IGAD) free movement protocol includes provisions allowing people displaced by disasters to enter other Member States and stay if return is impossible or unreasonable.

- Protections against return: The UN Human Rights Committee found in 2020 that immigrants have a right not to be returned to their places of origin if doing so would pose a risk to their right to life. This ruling has not been used to prevent deportation (the right to life threshold is quite high), but legal provisions in Canada, Italy, the United States, and other countries prevent deporting migrants to countries recently affected by severe disasters.

- Humanitarian protection: Argentina has adopted a small humanitarian visa program for disaster-displaced people from the Caribbean, Central America, and Mexico who could be sponsored to move and stay in the country. However, critical question remain around who qualifies, how they would be sponsored, and how they might obtain permanent legal status.

Other proposals include efforts to integrate climate-displaced people into existing labor, family, education, and other migration pathways, but these have not been well developed.

Can Migration Be Part of the Solution?

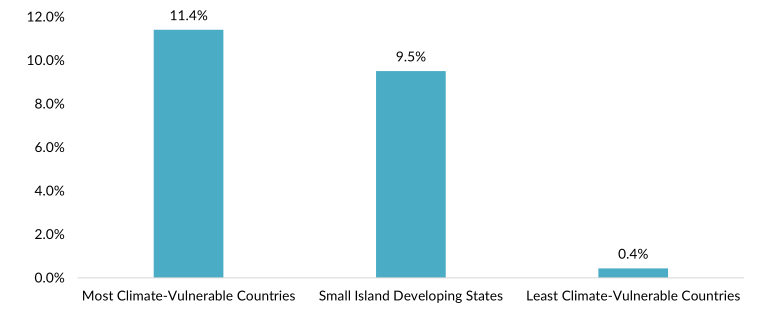

Mobility is not only a consequence of climate change but can be a strategy to adapt to it. The notion of migration as adaptation seeks to turn forced displacement into planned, voluntary migration that helps communities of origin and destination adapt to and mitigate the impacts of climate change. Migrants leaving climate-impacted communities who move to places where they earn higher wages can eventually help their origin communities adapt through the financial remittances they send back as well as the networks and ideas they acquire. Many climate-vulnerable countries are highly remittance-dependent, as are Small Island Developing States (see Figure 4). In 2021, Tonga was ranked the sixth most climate-vulnerable country, and remittances made up 46 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP).

Figure 4. Average Remittances as a Share of GDP, by Category, 2021

Notes: “Most Climate-Vulnerable Countries” are the ten with the highest vulnerability scores according to ND-GAIN for which remittance data are available (Somalia, Niger, Guinea-Bissau, the Federated States of Micronesia, Tonga, Sudan, Liberia, the Solomon Islands, Mali, and Afghanistan); “Least Climate-Vulnerable Countries” are the ten with the lowest vulnerability scores (Switzerland, Norway, Czechia, Finland, the United Kingdom, Germany, Austria, Canada, New Zealand, and Sweden); among Small Island Developing States, remittance data were not available for the Bahamas, the Cook Islands, Cuba, Nauru, Niue, or Singapore.

Sources: Author’s calculations based on World Bank/Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD), “Remittance Inflows,” June 2023 update, available online; ND-GAIN, “Vulnerability.”

Capturing the full potential of remittances has proven tricky. Movement partly depends on migration pathways, which are not always available to the most climate vulnerable. Moreover, remittances are not always reliable (they tend to surge after disasters, but not consistently) and often must be spent on food, education, and other immediate priorities, rather than longer-term adaptation measures such as raising houses to avoid flooding or acquiring drought-resistant crops.

Migration can also help destination countries move away from fossil fuels to green energy and toward more sustainable business practices. Many high-income countries that are among the largest greenhouse gas emitters lack necessary workers to build, install, and maintain solar panels and offshore wind farms, or retrofit buildings to be more energy efficient. The Boston Consulting Group has estimated there will be a gap of 7 million workers in the global green economy by 2030. Immigration is likely part of this solution, and immigrants already work in many jobs critical to the green transition such as chip manufacturing and solar installation. But there have been few policies to bring in migrant workers to fill green jobs.

Will Climate Change Drive Greater Movement?

Climate change is not the primary reason why most people move, nor is it the world’s most pressing migration challenge at present. But as disasters become more recurrent and severe, they can combine with economic and other troubles to trigger increased international migration. And as impacts of slower-onset climate change events affect livelihoods, more people might look to move.

Whether climate change triggers a spike in unsafe, unplanned, irregular migration will depend in large part on governments’ decisions to adapt to climate change and provide legal pathways and systems to help people move. Policies that seek to address climate migration are still in their infancy but are gaining attention as the ramifications of climate change become increasingly clear.

The author thanks Natalia Banulescu-Bogdan, Tosin Durodola, and Tino Tirado for their research support and review.

Sources

Ahmed, Munir. 2023. About 350 Pakistanis Were on Migrant Boat that Sank Off Greece and Many May Have Died, Official Says. Associated Press, June 23, 2023. Available online.

Allen, Samantha. 2023. 30% of Americans Cite Climate Change as a Motivator to Move in 2023. Forbes, October 9, 2023. Available online.

Boston Consulting Group. 2023. Will a Green Skills Gap of 7 Million Workers Put Climate Goals at Risk? September 14, 2023. Available online.

Clement, Viviane et al. 2021. Groundswell Part 2: Acting on Internal Climate Migration. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online.

European Investment Bank. N.d. 2019-2020 EIB Climate Survey (1/3). Accessed November 3, 2023. Available online.

Ficcarelli, Francesco Teo, Jane Linkear, and Roberto Forin. 2022. Climate-Related Events and Environmental Stressors’ Roles in Driving Migration in West and North Africa. Mixed Migration Centre briefing, Brussels, January 2022. Available online.

Forin, Roberto and Peter Grant. 2023. Pakistani Nationals on the Move to Europe: New Pressures, Risks, Opportunities. Mixed Migration Centre, July 31, 2023. Available online.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). 2023. Global Internal Displacement Database. Updated March 11, 2023. Available online.

Margesson, Rhoda. 2022. Pakistan’s 2022 Floods and Implications for U.S. Interests. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

McMahon, Simon et al. 2021. Population Exposure and Migrations Linked to Climate Change in Africa: Evidence from the Recent Past and Scenarios for the Future. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online.

Nash, Sarah and Caroline Zickgraf. 2020. Stop Peddling Fear of Climate Migrants. OpenDemocracy, September 23, 2020. Available online.

Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative (ND-GAIN). N.d. Vulnerability. Accessed November 4, 2023, Available online.

Ruiz Soto, Ariel G. et al. 2021. Complex Motivations and Costs of Central American Migration. Washington, DC: World Food Program, Migration Policy Institute, and the Civic Data Design Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Available online.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. Week 53 Household Pulse Survey: January 4 - January 16. January 25, 2023. Available online.