As Congress Tackles Immigration Legislation, State Lawmakers Retreat from Strict Measures

AZ Governor Jan Brewer in Washington in 2012 during the Supreme Court’s deliberations in the Arizona SB 1070 case. Enactment of high-profile laws affecting unauthorized immigrants has markedly dropped since the ruling. (MPI Staff Photo)

As national attention focuses on the immigration reform debate currently unfolding on Capitol Hill, state legislatures are retreating from their pursuit of restrictive immigration measures. Indeed, this retreat which began in 2012, is being accompanied by a rise in immigrant-friendly laws — a development that few would have predicted even just a year ago, as some states were racing to implement strict measures aimed at unauthorized immigrants.

A few factors have converged to contribute to this shift, notably the Supreme Court's decision in mid-2012 to strike down key parts of a restrictive Arizona immigration law, SB 1070, that had served as a model for other states. More broadly, the political climate and the tone surrounding immigration changed after the 2012 general election — both at the federal and state level.

The Slowdown and a Reversal

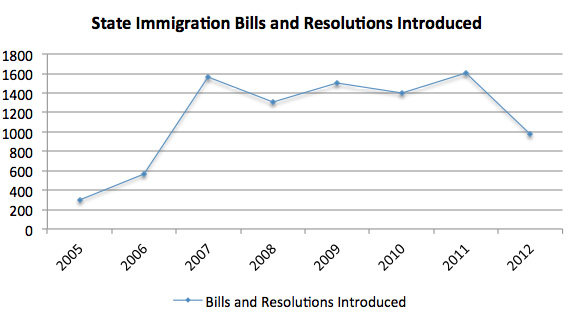

The flurry of immigration bills moving through state legislatures that began in the mid-2000s has abated. The number of immigration-related measures introduced by state lawmakers peaked in 2011. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 1,600 such measures were introduced in 2011, dropping by 39 percent to 983 in 2012. In 2012, 267 of these measures were enacted.

More importantly, enactment of high-profile omnibus immigration laws, like Arizona's SB 1070, has all but halted. After five states — Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, Utah, and Indiana — followed Arizona's lead in the passage of its 2010 law, just one such related bill — an amendment to Alabama's existing immigration enforcement law, was enacted in 2012. Omnibus immigration enforcement bills, intended to address the presence of unauthorized immigrants, typically span multiple areas, including immigration law enforcement, employment verification, and public benefits.

Figure 1. State Immigration Laws and Resolutions Introduced, 2005-12 | ||

|

In a significant reversal, Colorado, the first state to pass an omnibus immigration enforcement law in 2006, on April 26 repealed important provisions of that law — including one that required local police to alert federal authorities about immigrants suspected of being unauthorized.

Perhaps more striking, mandatory E-Verify laws, popular in the late 2000s and given a green light by the Supreme Court in May 2011, have slowed to a trickle. Such laws require some or all employers to use the federal government's electronic employer verification system, E-Verify, to determine whether new hires are authorized to work. In 2007, Arizona became the first state to require all employers to use E-Verify by enacting the Legal Arizona Workers Act (LAWA). Even after the Supreme Court upheld LAWA in Chamber of Commerce v. Whiting and opened the door for states to enact blanket mandatory E-Verify laws, Alabama was the only new state after Arizona to do so. Ten states passed more narrow E-Verify laws in 2011, and just three enacted such legislation in 2012.

Federal and State Courts Weigh In

The shift in direction by state legislators, perhaps not surprisingly, has coincided with various federal and state court decisions that have blocked key provisions of existing state laws. While the Supreme Court's ruling against key portions of Arizona's SB 1070 is perhaps the most notable, other federal and state courts also have rebuffed some state efforts to wade into an immigration enforcement territory that heretofore was almost entirely the province of the federal government.

Alabama's HB 56, arguably the nation's most strict state-level immigration law, was almost entirely enjoined by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit in August 2012. In April, the Supreme Court declined to hear the state's appeal, effectively leaving intact the lower court's decision. If not blocked, Alabama's law would have been more far-reaching than Arizona's SB 1070.

Last month, a U.S. district court in Atlanta permanently enjoined a key provision of Georgia's Illegal Immigration Reform and Enforcement Act of 2011, HB 87. In late March, a U.S. district court in Indiana also permanently enjoined parts of SB 590, the state's immigration enforcement law. Indiana state government officials have said they will not appeal the decision. Challenges to similar immigration laws in Utah and South Carolina are still before courts.

State courts have also begun to act. Most recently, a state district court in Montana struck down critical parts of LR 121, a ballot measure approved by voters in November 2012 that sought to bar noncitizens who entered the country illegally from accessing state services such as driver's licenses, employment, benefits, and financial aid. It is the first time that a Montana state court has ruled on the constitutionality of a state immigration measure.

The Shift

Not only have state lawmakers seemingly taken a hiatus from pursuing restrictive state-level immigration bills, in recent months, a number of them have also taken up pro-immigrant legislation — primarily facilitating unauthorized immigrants' access to in-state college tuition rates and driver's licenses.

In late April, Colorado reversed another element of its 2006 omnibus law, and allowed unauthorized students who graduate from Colorado high schools to attend public universities at the tuition rate that other in-state students pay.

Earlier that month, Oregon, on Democratic lawmakers' seventh attempt, joined the ranks of 13 other states that have enacted such tuition-parity laws. The others are: Texas and California in 2001, Utah and New York in 2002; Washington and Illinois in 2003; Kansas in 2004, New Mexico in 2005; Nebraska in 2006; Wisconsin in 2009; Maryland and Connecticut in 2011; and Colorado this year. Currently, five states — Alabama, Arizona, Georgia, South Carolina, and Indiana — affirmatively bar unauthorized immigrants from paying in-state tuition rates.

Allowing unauthorized immigrants to apply for driver's licenses, until recently considered politically hazardous, has found new acceptance in 2013. This year alone, the number of states allowing unauthorized immigrants to apply for driver's licenses has doubled, with Illinois, Maryland, and Oregon joining New Mexico, Utah, and Washington. In the case of Maryland, lawmakers reversed a 2009 law that barred driver's licenses for unauthorized immigrants. Legislation granting driving privileges to unauthorized residents is in various stages of development in a number of other states, including Colorado, Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Nevada, and Vermont. These developments are in sharp contrast to the climate of the late 2000s, when seven of the ten states that had originally allowed unauthorized access to driver's licenses reversed their policies.

Factors Responsible for the Shift

More than one factor is responsible for this shift in the winds from state capitals.

First, and perhaps most important, was the Supreme Court's landmark decision in Arizona v United States, striking down all but one of SB 1070's provisions. In the months before the high court's ruling, many states that had shown an eagerness to pass Arizona-type laws put those plans on hold, awaiting guidance from the justices. And as Arizona v United States was winding its way through the judicial system, the federal government challenged similar laws in all five states that passed them — Alabama, Utah, Indiana, South Carolina, and Georgia. In so doing, the federal government sent states a clear signal that similar laws would be challenged. One by one, the courts upheld the challenges — with the Supreme Court using its ruling in the Arizona case to forcefully affirm federal primacy in immigration law enforcement.

While the Supreme Court's ruling frustrated many states, it also prompted lawmakers to question the legal viability of their measures and the cost of bankrolling expensive and perhaps futile legal battles in a tightening fiscal environment.

The results of the 2012 presidential elections made lawmakers reassess the political viability of state activism in immigration politics. Post-election analysis suggested that Latino voters provided a crucial margin of victory for the Obama campaign in a number of contested states. With pundits describing the election results as a national rejection by Latino voters of restrictive immigration enforcement policies associated with the Republican Party and its standard bearer, Mitt Romney, the GOP began a post-election debate over its tone and policies regarding immigration.

Possible voter backlash against tough immigration enforcement measures also factored into state lawmakers' political calculus. After rising to national prominence as the champion of Arizona's SB 1070, state Senator Russell Pearce, who was Arizona Senate President, in November 2011 became the first Arizona lawmaker ever to be recalled by voters. The recall campaign, led by the grassroots organization Citizens for a Better Arizona, arose largely over Pearce's role in the passage of the state's controversial law.

A Lasting Trend?

The 2012 election created a new imperative for both parties to enact a major immigration overhaul — with Democrats recognizing the necessity to give back to a constituency that helped elect President Obama, and a growing cadre of establishment Republicans making the case that the GOP must recognize evolving demographic shifts and position itself to appeal to a growing bloc of Latino voters. Amid this new dynamic, the movement for strong action on immigration within the states has been slowed as state legislators wait to see if their frustrations with immigration policy will be addressed by Washington.

They also are bracing to understand the impacts that comprehensive immigration reform, which would include legalization for many of the nation's estimated 11 million unauthorized immigrants, would have on all 50 states. Among the issues for states to consider: how to address a newly legalized population. Among the considerations would be state actions to address integration measures, such as increasing access to English as a Second Language classes and workplace training, as well as to determine immigrants' eligibility for state benefits.

However, if Congress fails to pass immigration reform legislation, the states will once again find themselves witnesses to federal inaction, and will perhaps acquire a renewed appetite to pass immigration laws of their own.

- See the National Conference on State Legislatures' report on 2012 Immigration-Related Laws and Resolutions in the States.

- Learn more about Alabama v. United States journey through the courts.

- Read a copy of the Supreme Court's opinion in Arizona v. United States.

- Learn more about in-state tuition and unauthorized immigrant students through NCSL.

- Read Stateline's article on recent pro-immigration victories in states.

- Read a copy of Colorado's Community And Law Enforcement Trust Act here.

- Read a copy of Oregon's new law, H.B. 2787.

- Read the permanent injunction against Georgia's law, HB 87.

- Read Indiana's SB 590.

- Read the ruling on Montana's law.

Policy Beat in Brief

Immigration Reform Bill Clears Senate Judiciary Committee. On May 21, the Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act (S. 744) passed out of the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee on a vote of 13-5 after the markup process on the bill was completed. The bill was supported by all ten committee Democrats and three Republicans — Orrin Hatch (UT), Lindsey Graham (SC), and Jeff Flake (AZ).

Of the some 300 amendments submitted before consideration of the bill began, more than 200 were debated over the course of five days. The four senators on the committee — Sens. Richard Durbin (D-IL), Flake, Graham, and Charles Schumer (D-NY) who are also part of the so-called Gang of Eight, the bipartisan group that negotiated and crafted the bill — coordinated their votes to defeat any amendment seen as threatening to the bill's key principles and to accept those they felt strengthened the legislation. Some key changes to the bill adopted during markup included more ambitious border security goals, revised H-1B provisions that address business concerns, stricter treatment of criminals, more rigid asylum policies, increased congressional oversight, and numerous new information-sharing requirements.

S. 744 is expected to move to the Senate floor sometime in June. A large number of amendments are sure to be offered before it is put to a vote. The bill may face a filibuster, which requires 60 votes to overcome. The sponsors of the bill are aiming for at least 70 yes votes. S. 744 proposes to reform the U.S. immigration system by strengthening border security and workplace enforcement, offering an earned legalization program for the estimated 11 million unauthorized immigrants living in the country, and revamping the permanent and temporary legal immigration systems.

- Read S. 744 (the manager's amendment).

- See which amendments were debated, adopted, withdrawn, and not agreed to.

First DACA Denials are Issued by USCIS. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) began issuing its first denials under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. According to a USCIS report, as of April 30, the agency has denied 2,352 cases. USCIS has accepted a total of 497,960 applications, 291,859 of which have been granted. The DACA program, which President Obama announced last June, allows certain unauthorized immigrant youths who arrived in the United States as children to apply for work permits and temporary protection against deportation. The average number of applications accepted daily in April was 1,181 — down from 1,414 in March. The average peaked in September and October at over 5,000 applications accepted per day, but has since dropped to under 2,000 from January forward, suggesting that demand for the program has leveled off.

- See the most recent DACA statistics.

Extra Screening for Foreign Students Ordered. In early May, Homeland Security (DHS) Secretary Janet Napolitano issued an internal memorandum ordering Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) officers to verify the visa validity of all foreign students entering the United States, effective immediately. The new policy comes in response to the revelation that a friend of one of the Boston marathon bombing suspects, charged with obstruction of justice after tampering with case evidence, had been able to re-enter the United States in January even though his student visa had been terminated. The memo seeks to facilitate the sharing of information between DHS' student visa database SEVIS and the databases used by CBP to make admissions decisions. CBP officers are now required to manually verify through SEVIS that foreign students seeking entry still hold valid student visas.

- Read about the CBP memo.

Unaccompanied Minors on the Rise. During the first six months of FY 2013, DHS officials detained over 6,500 unaccompanied minors at the U.S.-Mexico border, nearly double the number detained during the same time period last year. The majority is from Guatemala, Honduras, or El Salvador, and is between the ages of 14 to 17. While the entire southwest border has seen increasing numbers of unaccompanied minors, South Texas has experienced a particularly substantial influx, leading the federal government to open five temporary shelters in the region. Experts speculate that a new immigration law in Mexico that permits Central American youth to stay in the country without a visa for humanitarian reasons has contributed to the surge, as it has made it easier for these youth to reach the U.S.-Mexico border. The rise in arrivals of unaccompanied minors has occurred while overall estimated unlawful entries are on the decline.

- See the Wall Street Journal article on unaccompanied minors.

Mexico Becomes the Second Leading Source for Asylum Claims. Asylum claims by nationals of Mexico brought before U.S. immigration courts have tripled in the last five years, making Mexico the second largest source of asylum seekers after China. In 2012, the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) received 9,206 asylum applications from Mexican nationals, compared to 10,985 from Chinese nationals. There are two ways that noncitizens may request asylum: affirmatively, by applying with a DHS asylum officer; or defensively, by requesting asylum before an immigration judge. DHS and EOIR data indicate that grants of asylum to Mexicans remain low, but have increased in recent years, from 103 affirmative and 73 defensive approvals in 2008 to 337 affirmative and 126 defensive approvals in 2012. In total, 11,978 individuals from all countries were granted asylum defensively and 17,506 were granted asylum affirmatively in 2012. To be granted asylum in the United States, a noncitizen must demonstrate past persecution or a well-founded fear of future persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

- Explore asylum data in EOIR's 2012 Statistical Yearbook.

- Find data on refugees and asylees from the Office of Immigration Statistics.

- Read the article from The Dallas Morning News about asylum seekers from Mexico on HeraldNet.

Southern Texas Overtakes Arizona for Largest Number of Immigration Prosecutions. According to a new Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) report on prosecutions for immigration offenses for the first six months of FY 2013, the Southern District of Texas (Houston) tops all other regions with 17,022 immigration prosecutions to date this year. The Western District of Texas is the next leading source of immigration prosecutions with 13,379, followed by Arizona with 11,476. Arizona, which saw the highest number of prosecutions in FY 2012, fell to third place with a 22 percent decline, the largest drop of any district. For FY2013, so far, the number of prosecutions is 9.8 percent higher than last year for a total of 50,468. If such prosecutions continue apace, FY 2013 will see a record number of prosecutions for immigration offenses, which have already occurred at historically high levels since 2008. Common immigration offenses include improper entry, re-entry after deportation, and bringing in or harboring certain noncitizens.

- Read the TRAC report.