You are here

Criminalization of Search-and-Rescue Operations in the Mediterranean Has Been Accompanied by Rising Migrant Death Rate

Sailors and marines on the HMS Bulwark help migrants ashore in Italy. (Photo: PO Carl Osmond/Royal Navy)

The deaths of more than 350 migrants in the 2013 sinking of an overloaded smuggling vessel off the Italian island of Lampedusa shocked the world and reignited debate over the European Union’s response to the increasing numbers of asylum seekers crossing the Mediterranean Sea. At first, frontline EU Member States moved swiftly to set up search-and-rescue operations, adopting an approach in keeping with international conventions such as the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, which require rescue of “persons in distress” in states’ territorial waters regardless of their legal status.

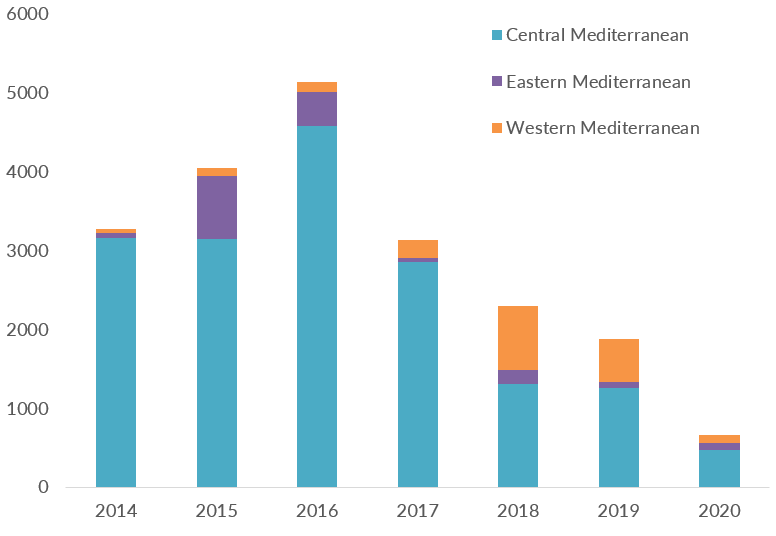

This response proved short-lived. The European Union changed its approach at the height of the 2015-16 migration crisis, when approximately 1.4 million asylum seekers and migrants reached Europe via the sea. Shifting from a decentralized system of national rescue operations, the bloc instead concentrated on border management via Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, and prioritized erecting obstacles to reaching its borders, increasing surveillance, and criminalizing search-and-rescue operations by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). This move towards securitization made the sea passage more dangerous and difficult but did not reduce migrant deaths. Instead, years after the crisis, the Central Mediterranean Route (CMR) has been responsible for more migrant deaths than any other waterway in the world, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Approximately half of the more than 38,000 migrant deaths and disappearances globally recorded by IOM between January 2014 and October 2020 occurred in the Mediterranean; of these, 82 percent have been in the Central Mediterranean. Moreover, even as overall crossings have declined, the death rate has been going up: in 2019, one in 21 people who attempted the crossing died, slightly more than double the rate of 2016. It is difficult to establish direct causation, but migrant advocates and humanitarian responders have linked the policy changes restricting NGO search-and-rescue activities to this increased death rate.

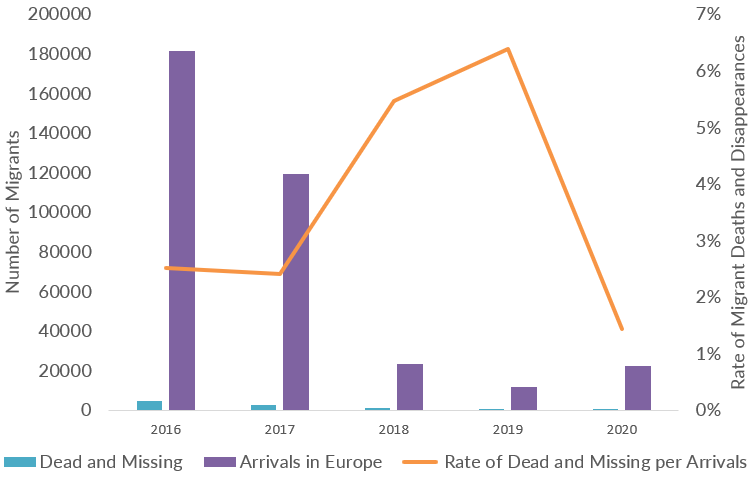

While paths across the Mediterranean can overlap, the CMR, which runs from North Africa to either Italy or Malta, is one of three main sea routes; others take migrants from Morocco to Spain, from Turkey to Cyprus, or across the Aegean from Turkey to Greece. Nearly 14,000 people successfully disembarked in Italy or Malta in 2019, many after spending days at sea, and often aided by a robust smuggling industry in Libya that has ballooned since the 2011 overthrow of leader Muammar Gaddafi. The national origins of asylum seekers and other migrants vary by route and time period, but in 2019 most travelers along the Central Mediterranean were from Tunisia, Pakistan, or Côte d’Ivoire. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that at least one-third of those who arrived in Europe via the Central Mediterranean in 2018 were in need of international protection, among them unaccompanied or separated children, who accounted for 15 percent of migrants arriving in Italy in 2019. Although fewer people traveled the CMR in 2019 than any year since 2012, the rate of migrant deaths and disappearances relative to arrivals along this route has steadily increased, more than doubling from 2016 to 2019, from 2.4 percent to 6.4 percent. This rate dropped dramatically in 2020, potentially due to higher numbers of migrants departing in sturdier vessels from Tunisia, changes in movement patterns due to the coronavirus pandemic, and other factors.

Figure 1. Number and Rate of Migrant Deaths and Disappearances along the Central Mediterranean Route, 2016-20

Note: Data for 2020 are for arrivals in Italy and go through September 20.

Source: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Europe: Dead and Missing at Sea,” fact sheet, UNHCR, Geneva, January 2020, available online; UNHCR, “Italy Weekly Snapshot: 20 Sept 2020,” fact sheet, UNHCR, Geneva, September 2020, available online.

This article evaluates the evolution of European policy regarding Central Mediterranean crossings, which initially was grounded in a search-and-rescue frame following the Lampedusa shipwreck but subsequently took on a hardened security lens. Europe’s approach shifted to prioritize enforcement against migrants at sea and criminalization of NGOs that launched their own search-and-rescue operations, sometimes to great publicity, as when the British artist Banksy financed a vessel in mid-2020. In the process, European leaders made the route more treacherous for migrants.

Initial Policy Response: Member State-Led Search and Rescue

Most migrants crossing the Central Mediterranean to Europe arrive in Italy. At the time of the Lampedusa shipwreck, Italian policy had largely taken a humanitarian approach to sea arrivals, rather than one focused on border enforcement. Officials often rescued asylum seekers and other migrants from vessels in distress, allowing them to disembark and undergo asylum processing in southern Italy. Following the Lampedusa shipwreck, the Italian government launched Operation Mare Nostrum, a search-and-rescue program with a monthly budget of 9 million euros, in an effort to decrease the number of deaths at sea. As a maritime security operation involving units from the Italian Navy and Air Force, Mare Nostrum spanned 70,000 square kilometers of the Mediterranean, including areas strategically positioned around the Libyan coast. The operation was equipped with two submarines, coastal radar technology, helicopters with infrared capability, drones, and 900 staff. Mare Nostrum proved to be highly effective in minimizing deaths at sea, rescuing nearly 156,400 people during its single year of existence. Moreover, the operation proved to be successful at identifying and apprehending smugglers; it was responsible for the arrest of more than 350 smugglers and the confiscation of nine ships.

Despite its objective success at minimizing maritime deaths, however, Mare Nostrum’s high cost and the refusal of other EU states to contribute to its funding eventually made the operation politically unsustainable. Increasing anti-immigrant sentiment and political pressure from within Italy and other Member States contributed to its termination in October 2014. Critics of Mare Nostrum cited it as a “pull factor” responsible for the uptick in migrant crossings in 2014. Within Italy, growing resentment of the lack of European support justified its dissolution; then-Interior Minister Angelino Alfano argued that “Italy could not and should not take charge of the Mediterranean border on its own.”

The end of Mare Nostrum heralded a dramatic decrease in Europe’s willingness and capacity to conduct search and rescue. In its place came a policy focused on centralized border management, characterized by border-control agreements with origin or transit countries such as Libya, the conditioning of development aid including the EU Trust Fund for Africa on migration management agreements, and the criminalization of civil-society rescue operations in its territorial waters. The consequences have been fatal.

From Search and Rescue to Border Externalization and Criminalization

Following the termination of Operation Mare Nostrum, surveillance and enforcement activities at Europe’s external borders were taken over by Frontex. Established in 2004 as the European Agency for the Management of Operational Cooperation at the External Borders, Frontex was given an initial mandate to coordinate Member States’ border control, facilitate intelligence sharing, and assist in returning third-country nationals entering the bloc without authorization.

In November 2014 the agency launched Operation Triton, whose primary focus on border surveillance and enforcement illustrated the shift in priorities. With less than one-third the funding of its predecessor and only 65 personnel, Triton initially confined its area of operations to a mere 30 nautical miles beyond the Italian coastline, severely limiting its capacity to conduct search-and-rescue activities. Fabrice Leggeri, Frontex’s head since January 2015, insisted that Triton had not been designed to replace Mare Nostrum, whose activities he said had bolstered Libya’s smuggling trade. Search-and-rescue operations were “not in Frontex’s mandate, and this is in my understanding not in the mandate of the European Union,” he said in 2015. “We should not support and fuel the business of traffickers.”

After more than 1,200 migrants died in two shipwrecks in April 2015, Frontex expanded Triton’s reach to 138 nautical miles off the Italian coast and the European Union launched a military mission, European Union Naval Force Mediterranean (EU-NavFOR Med), also known as Operation Sophia, to more comprehensively address trafficking and smuggling. Sophia extended its patrol activities into Libya’s territorial waters and focused on targeting smugglers’ vessels. To evade these patrols, smugglers abandoned traditional wooden vessels in favor of cheaper, unseaworthy rubber dinghies without engines, which were often towed by skiffs and then left adrift. A 2017 European Commission joint communication noted the consequences of these changes, concluding that the large number of dinghies “contributes to making journeys increasingly dangerous and to the rise in the number of deaths at sea.” While the rhetoric of both missions suggested that humanitarian operations remained a core component of EU policy, neither operation had a specific search-and-rescue mandate, and the proportion of rescues conducted by Triton and Sophia steadily decreased during their tenures. For example, according to data collected by the Italian Coast Guard, Triton was responsible for 24 percent of total rescues in 2015, but for just 13 percent by 2017.

In December 2015, at the height of the migration and refugee crisis, the European Commission proposed expanding Frontex’s mandate, making it responsible for managing the entirety of the European Union’s borders and giving it executive powers similar to those of national border agencies. Many legal scholars and human-rights activists were quick to condemn what they saw as the potential for abuse of these executive powers. They were particularly concerned about agency accountability for human-rights abuses committed in remote locations such as on the high seas, during joint return flights, and in third-country detention centers, as well as the challenges associated with guaranteeing adequate mechanisms for reporting and addressing complaints by foreign nationals outside EU territorial waters.

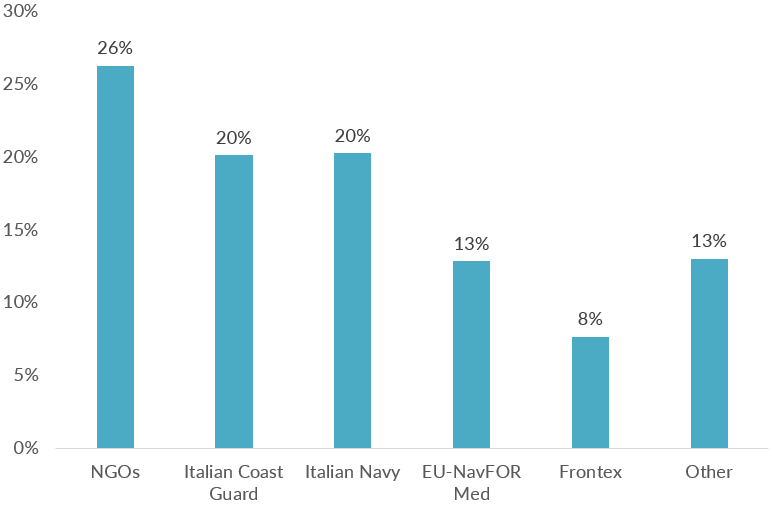

The number of migrants crossing the Mediterranean by sea into Europe reached a peak of more than 1 million in 2015, precipitated largely by upheaval from the Syrian civil war. This represented an almost six-fold increase in migrant arrivals since the previous year, and though this number dropped to about 360,000 by the end of 2016, it still constituted more than twice the previous average of annual arrivals. In response to this spike in crossings and the void left by changing EU policy, maritime NGOs began to expand their search-and-rescue operations. Between 2015 and 2016, the number of nongovernmental search-and-rescue vessels active along the CMR more than tripled, from four to 13, according to the Italian Coast Guard. Groups such as Médecins Sans Frontières, Sea-Watch, and Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS) became important search-and-rescue actors in the Mediterranean, accounting for 26 percent of all rescues in 2016. The Italian Navy (20 percent) and Coast Guard (20 percent) also accounted for significant operations, while EU-NavFOR Med accounted for about 13 percent and Frontex just 8 percent of total rescues that year. NGOs’ importance rose over time to account for 38 percent of total rescues in 2017 and 40 percent of rescues by the first half of 2018.

Figure 2. Proportion of Rescues in the Central Mediterranean by Actor, 2016

Source: Italian Coast Guard, Attività Sar nel Mediterraneo Centrale connesse al Fenomeno Migratorio (Rome: Italian Coast Guard, 2016), available online.

Italy-Libya Deal

In 2017, the Italian and Libyan governments signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) placing responsibility to intercept and return smugglers and migrants with the Libyan coast guard. In exchange, Libya received significant development funding from the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, border enforcement training for its coast guard, and financing and medical equipment for its migrant detention centers. Although Italy had negotiated with Gaddafi to curb migration and crack down on smuggling operations throughout the 2000s, this was the first externalization agreement the two countries signed since the outbreak of the Libyan civil war and the 2012 European Court of Human Rights verdict in Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy. The decision in that case found Italy responsible for violating the principle of nonrefoulement by returning asylum seekers from the Maltese area of responsibility back to Libya. The MoU was renewed in early 2020.

This redirection of responsibility for preventing migrants from reaching Europe to Libyan authorities has resulted in more instances of arbitrary detention and a spike in detention-related abuses in Libya. Human-rights groups have argued that the MoU directly implicates Italy and the European Union more generally in the large-scale violation of asylum seekers’ rights. Reports indicate that conditions in Libyan detention centers—where hunger strikes, overcrowding, riots, torture, lack of medical care, and physical and sexual abuse run rampant—consistently violate human-rights standards. Although Libyan authorities have been well funded by the European Union, the country remains in the midst of civil war, and coast guard leaders include an assortment of former smugglers and militia members.

Criminalization Takes the Lead

The Italy-Libya agreement and Frontex’s prioritization of anti-smuggling surveillance was accompanied by the increased criminalization of NGOs’ search-and-rescue activities. Until 2013, Member States in the Mediterranean had discouraged private vessels from fulfilling their international obligations to rescue people in distress but did not prosecute them for it. This changed after the expansion of Frontex’s powers in 2015, and EU members began actively prosecuting NGOs involved in rescue activities, seizing and impounding their vessels, and charging crew members with facilitating illegal immigration. Data collected by the EU Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) show that 17 NGO ships were involved in legal proceedings between 2017 and June 2020. NGOs have nonetheless continued to intervene in rescue activities at their own risk. In the process, some activists have emerged as unlikely celebrities, such as Sea-Watch ship captain Carola Rackete, who squared off against the Italian government, and Pia Klemp, who commands the Banksy-funded rescue boat Louise Michel.

In 2017, as a result of intense political pressure, NGOs operating in the Mediterranean agreed to sign a code of conduct, drafted by Italy in consultation with the European Commission, which prohibited search-and-rescue activities in Libyan territorial waters and enacted other restrictions. Because of the MoU with Libya, the new code of conduct effectively limited the NGO ships’ available scope of rescue to European territorial waters and redirected most responsibility for search and rescue to Libyan authorities.

Italy and Malta have prevented civil society search-and-rescue vessels from disembarking at their ports since 2018. The following year, with the backing of then-Interior Minister Matteo Salvini, Italy’s Parliament adopted a law imposing fines of up to 1 million euros and automatically impounding private vessels found to be conducting rescue activities. European states affected by irregular sea arrivals, including Italy, Greece, Spain, and Malta, since 2015 have pursued legal cases against individuals and NGOs for their humanitarian intervention, alleging crimes such as facilitation of irregular immigration, human smuggling, membership in a criminal organization, and money laundering. According to FRA, more than 40 criminal investigations have been initiated by European states since 2017, of which a dozen remain pending. For example, in 2017 Italy pressed charges against the crew of the German NGO Jugend Rettet’s Iuventa for their activities off the Libyan coast; the Italian NGO Mediterranea Saving Humans had two vessels impounded for several months starting in mid-2019. Frontex’s Operation Sophia was ended in March 2020, after a year of operating without naval vessels, a change made under pressure from Salvini. It was replaced with Operation Irini, which focuses solely on enforcing an arms embargo against Libya.

NGOs, meanwhile, have directly blamed the European Union and its Member States for the increased rate of migrant deaths in the Mediterranean. Their leaders have criticized governments for scaling back search-and-rescue operations while targeting private rescuers. Médecins Sans Frontièrs stated: “Not only has Europe failed to provide search-and-rescue capacity, it has also actively sabotaged others’ attempts to save lives.”

Figure 3. Number of Recorded Deaths Along Different Mediterranean Migration Routes, 2014-20

Note: Data for 2020 are through October 4.

Source: International Organization for Migration (IOM), “Missing Migrants Project,” accessed October 4, 2020, available online.

The Humanitarian Consequences of the Deterrence Strategy

These policies reflect a broader trend towards border securitization that has served to distance the European Union from its obligation to protect migrants and asylum seekers. Government leaders often justify the scaling back and criminalizing of search-and-rescue activities by claiming that the availability of rescue acts as a pull factor for migration, and therefore as an incentive for smuggling. This argument relies on the assumption that increasing border surveillance and securitization deters migration. However, this has mostly not been supported by scholarship. Regression modeling on irregular migration from Libya to Italy conducted by scholars Eugenio Cusumano and Matteo Villa found that the only statistically significant indicators of increased migration were weather conditions and Libya’s political stability, while NGOs’ presence had no significant effect.

Restrictive migration policies may serve as a deterrent in the sense that they reroute irregular traffic from the Central Mediterranean to other routes. However, survey data and migrant interviews do not suggest that policy restrictions generally deter individuals from their decisions to migrate. Research by the interagency Mixed Migration Hub conducted in 2018 found that, compared to the CMR, the Western Mediterranean—which at the time was experiencing a surge in migrant traffic—was “perceived as safer, less expensive, and relatively ‘easier’ by those traveling on this route.” Although maritime arrivals to Italy dropped by 80 percent between 2017 and 2018 and then by another 51 percent between 2018 and 2019, overall traffic through the Mediterranean did not decline at the same rate, suggesting that deterrence-focused measures only served to redirect traffic to less-restricted routes.

The externalization of border management and the increasing criminalization of search-and-rescue interventions by maritime NGOs has had significant negative humanitarian consequences for migrants both at sea and upon return to third-country points of departure, particularly Libya, where lack of oversight and indiscriminate detention practices threaten their basic human rights. Human-rights experts affiliated with the United Nations have expressed concern that restrictions on NGOs’ search-and-rescue operations “put the lives of thousands of migrants attempting to cross the sea at risk,” and that criminal charges “could have a chilling effect on migrant-rights defenders and on civil society as a whole.”

These policy changes have already resulted in fatal consequences and are likely to continue to seriously endanger the rights and lives of migrants transiting through the Central Mediterranean. As long as border management policies continue to ignore the systemic causes of irregular migration in favor of exclusionary border securitization, Europe’s commitment to international obligations to migrants and asylum seekers will continue to ring hollow and deaths will continue to rise. These deaths are not inevitable. Yet by failing to take meaningful action to reduce them, Europe is effectively sending the message that migrant deaths at sea are an unfortunate but acceptable consequence of irregular migration.

Sources

Borger, Julian. 2015. EU under Pressure over Migrant Rescue Operations in the Mediterranean. The Guardian, April 15, 2015. Available online.

Cusumano, Eugenio. 2017. Straightjacking Migrant Rescuers? The Conduct on Maritime NGOs. Mediterranean Politics 24 (1): 106-14. Available online.

---. 2019. Migrant Rescue as Organized Hypocrisy: EU Maritime Missions Offshore Libya Between Humanitarianism and Border Control. Cooperation and Conflict 54 (1): 3-24. Available online.

Cusumano, Eugenio and Matteo Villa. 2020. From “Angels” to “Vice Smugglers”: The Criminalization of Sea Rescue NGOs in Italy. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research: 1-18. Available online.

Cuttitta, Paolo. 2017. Repoliticization Through Search and Rescue? Humanitarian NGOs and Migration Management in the Central Mediterranean. Geopolitics 23 (3): 632-60. Available online.

Dearden, Kate, Marta Sánchez Dionis, Julia Black, and Frank Laczko. 2020. Calculating “Death Rates” in the Context of Migration Journeys: Focus on the Central Mediterranean. Berlin: International Organization for Migration, Global Migration Data Analysis Centre. Available online.

European Commission. 2017. Migration on the Central Mediterranean Route: Managing Flows, Saving Lives. Joint Communication to the European Parliament, the European Council, and the Council, January 25, 2017. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). N.d. Missing Migrants Project. Accessed October 5, 2020. Available online.

Italian Coast Guard. 2016. Attività Sar nel Mediterraneo Centrale connesse al Fenomeno Migratorio. Rome: Italian Coast Guard. Available online.

---. N.d. Attività S.A.R. (Search and Rescue) nel Mediterraneo Centrale Dal 1 Gennaio al 31 Diciembre 2018. Accessed October 2, 2020. Available online.

Kingsley, Patrick and Ian Traynor. 2015. EU Borders Chief Says Saving Migrants’ Lives ‘Shouldn’t Be Priority’ for Patrols. The Guardian, April 22, 2015. Available online.

Last, Tamara and Thomas Spijkerboer. 2014. Tracking Deaths in the Mediterranean. In Fatal Journeys: Tracking Lives Lost During Migration, eds. Tara Brian and Frank Laczko. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. Available online.

Libyan Government of National Accord and Italian Government. 2017. Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation in the Fields of Development, the Fight against Illegal Immigration, Human Trafficking and Fuel Smuggling and on Reinforcing the Security of Borders between the State of Libya and the Italian Republic. February 2, 2017. Available online.

Mestchersky, Sophie. 2019. Investigating Evolving Profiles, Intentions, Experiences and Vulnerabilities of People on the Move on Central Mediterranean and Western Mediterranean Routes in 2018. Cairo: Mixed Migration Hub. Available online.

Migration Data Portal. N.d. Migrant Deaths and Disappearances. Last updated 17 March, 2020. Available online.

Mixed Migration Hub. 2018. The Central Mediterranean Route: The Deadliest Migration Route. In Focus, March 2018, Mixed Migration Hub, Cairo, March 2018. Available online.

Palm, Anja. 2017. The Italy-Libya Memorandum of Understanding: The Baseline of a Policy Approach Aimed at Closing All Doors to Europe? EU Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy, October 2, 2017. Available online.

Patalano, Alessio. 2015. Nightmare Nostrum? Not Quite: Lessons from the Italian Navy in the Mediterranean Migrant Crisis. The RUSI Journal 160 (3): 14-19. Available online.

Restelli, Gabriele. 2019. The Policy Tap Fallacy: Lessons from the Central Mediterranean Route on How Increasing Restrictions Fail to Reduce Irregular Migration Flows. Policy Paper No. 1, Mixed Migration Centre, Cairo, June 2019. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2015. UNHCR Central Mediterranean Sea Initiative. Action Plan, March 2015. Available online.

---. 2019. Desperate Journeys: Refugees and Migrants Arriving in Europe and at Europe’s Borders, January-December 2018. Geneva: UNHCR. Available online.

---. 2020. Europe: Dead and Missing at Sea. Fact Sheet, UNHCR, Geneva,January 2020. Available online.

---. 2020. Italy Weekly Snapshot 20 September 2020. Fact Sheet, UNHCR, Geneva, September 2020. Available online.

United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR). 2019. Italy: UN Experts Condemn Criminalisation of Migrant Rescues and Threats to the Independence of Judiciary. Press release, July 18, 2019. Available online.