The Czech Republic: From Liberal Policy to EU Membership

Since regaining its freedom in 1989 and peacefully splitting from the Slovak Republic in 1993, the Czech Republic has been transforming its former socialist/communist society into a democratic, parliamentary one based on a free-market economy. In 1999, the country joined NATO, and, in 2004, the European Union (EU), along with a number of other former communist states.

Like many other Eastern European countries, the Czech Republic has transformed in the last 15 years from a land of emigration to one of transit and immigration. Out of a total population of 10.2 million, 252,000 people (or 2.5 percent) in the Czech Republic in 2004 were legal immigrants. In 1993, this figure stood at just 0.8 percent. The number of illegal immigrants is estimated at 300,000 to 340,000.

The capital city, Prague, other big cities, and areas near the borders have attracted the most migrants, causing the labor market to fragment into sectors dominated by natives and immigrants.

Not surprisingly, the country is confronting a number of migration-related issues, including illegal migration, the need for high-skilled migrants, asylum seekers and refugees, discrimination against migrants, and trafficking. In addition, EU membership has made these issues more complex, especially since migration policies and practices are still developing.

Historical Migration Patterns

The first wave of people from what is now Germany arrived in the 13th and 14th centuries. They settled in newly established towns, villages in border zone areas, and in highlands, and they played an important role in Czech lands (Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia) until the end of the 1940s.

Prague, although a predominantly Czech city throughout its history, was also home to Germans and Jews. Prague was an important Jewish center in Europe for centuries despite periodic expulsions; about one-fourth of the city's population in the first half of the 18th century was Jewish. In the second half of the 18th century, the Hapsburg administration "Germanized" Prague, making the German language dominant.

The territory that now includes the Czech Republic was already under Austrian control when it became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1867. Between 1850 and 1914, approximately 1.6 million people, most of them agricultural and industrial workers, went to the United States, Canada, Argentina, Brazil, Austria, Hungary, Russia, and countries of the former Yugoslavia in search of economic opportunities.

After World War I, the state of Czechoslovakia — consisting of the present-day territories of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Carpathian Ruthenia (Carpatho-Ukraine) — was founded as one of the succession states of Austria-Hungary. The new parliamentary democracy established Czech and Slovak as official languages, and protected the rights of Germans and other ethnic minority groups, allowing them to have educational and cultural institutions.

According to the Czechoslovakian census, in 1921 there were about three million Germans, composing 30.6 percent of the population. In the interwar period, more Germans than Czechs worked in its booming industrial sector, mainly in light branches like glass and textiles. Few Germans left Czechoslovakia during this time; their share of the population stood at 29.5 percent in 1930 and 29.2 percent in September 1938.

Between the wars, the second largest, albeit much smaller, ethnic community in the Czech lands of Czechoslovakia were Poles, who composed one percent (92,689) of the population in 1930. There were also about 44,000 Slovaks living in the Czech lands at that time.

After the formation of Czechoslovakia, people continued to emigrate for economic and family reunification reasons, mainly to the U.S., France, and Germany. This emigration flow peaked in the early 1920s, but continued until the end of the 1930s. Following World War I, 40,000 Czechs returned from the U.S. and about 100,000 returned from Austria. The flow of returnees was smaller than the emigration flow, and the Czech Republic's population decreased in this interwar period.

In the fall of 1938, European leaders decided to appease Hitler and forced Czechoslovakia to cede the Sudetenland, the region where most ethnic Germans lived, to Germany; Poland and Hungary also claimed strategic territory.

In March 1939, Slovakia declared independence and came under the protection of Nazi Germany. Hitler then invaded Czech lands and proclaimed Bohemia and Moravia a German protectorate; the region remained under Nazi Germany's control until the end of World War II in 1945, when the pre-war Czechoslovakia was reestablished.

Although thousands of Czech Jews escaped, an estimated 80,000 perished in death camps and concentration camps. By 1945, only 13,000 Jews remained, and about half emigrated to Israel by 1950.

Between 1945 and 1946, approximately 2.8 million Germans (some 25 percent of Czechoslovakia's population of that time) were expelled from the country, with most "returning" to Germany. About 1.3 million Germans were sent to the American zone, which later became West Germany, and in a second, more organized wave, 800,000 went to the Soviet Zone (later East Germany). During this period, thousands of Germans died due to violence, hunger, and illness.

Germans were only allowed to stay if they could prove they had fought against Nazism during the war or if they came from a Czech-German marriage. According to the 1950 census, only 160,000 Germans remained in the Czech Republic, just 1.8 percent of the total population (8.9 million) that year.

During the communist era (1948 to 1989), highly skilled Czechs and Slovaks continued to leave the country despite the risks. From 1950 through 1989, it is estimated that more than 550,000 people emigrated. Emigration meant breaking all family ties and social networks because those who left were not allowed to return. In addition, emigration was considered a criminal offense. The consequences included confiscation of possessions and sometimes the persecution of relatives.

The two main emigration waves came in 1948, when the communists came to power, and in 1968, when the Soviet Union and its Eastern European allies invaded the country. Western European countries, in particular Germany, but also traditional immigration regions such as the U.S., Canada, and Australia, were the emigrants' destinations. They were considered refugees and were welcomed in these host societies.

Reasons behind this highly skilled emigration were mostly political and economic. Some people could no longer bear the anti-democratic and totalitarian regimes while others were dissatisfied with their general standard of living.

Although few people from other communist states permanently settled in Czechoslovakia, temporary workers from countries under Soviet influence — including Angola, Cuba, Vietnam, Mongolia, and Poland — came to gain skill and work experience. At the same time, they filled gaps in the Czech labor market.

This system of recruiting students, apprentices, and workers functioned via intergovernmental agreements and, to a much lesser extent, also through individual contracts (mainly with workers from Poland and Yugoslavia). These immigrants usually stayed several years and were involved in various branches of the economy, such as food-processing, textiles, shoe and glass industries, machinery, mining, metallurgy, and agriculture.

Migration Since 1989

When the Czech Republic split from Slovakia in 1993, it carried over some migration provisions from the 1989-1992 Czechoslovakia period.

More importantly, in 1993 the newly independent country established a liberal migration policy that, coupled with the country's geographic position, helped the Czech Republic become home to tens of thousands of migrants from Europe and Asia during the 1990s. The majority have been economic migrants and their families, but many quasi-legal migrants who made use of loopholes in the legislation have also entered.

Illegal immigrants include transit migrants seeking to reach a classical, "Western" country as soon as possible. In the early1990s, the UN estimated that between 100,000 and 140,000 transit migrants were in the Czech Republic. A smaller group were mostly skilled immigrants from North America and Western Europe who chose not to complete time-consuming registration procedures.

In the mid-1990s, thousands of Czech Roma applied for asylum in first Canada and then the UK. The Roma — an ethnic group spread across Europe that can be traced back to northern India — have faced high levels of discrimination, unemployment, and poverty.

Generally, few Roma from the Czech Republic and other Eastern European countries have received asylum based on the criteria of the 1951 Geneva Convention, which says refugees must have been persecuted or have a well-founded fear of persecution due to race, nationality, religion, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.

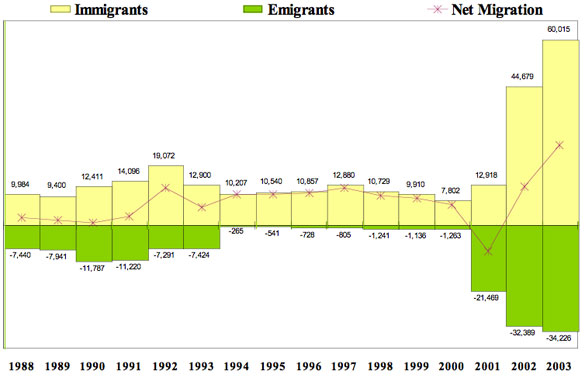

Emigration, which initially increased in the years just after independence in 1989, dropped significantly after 1993 to an average of about 850 emigrants per year, according to official records. In 2001, the government began to include short-term and temporary migrants in its immigration and emigration statistics, which is why those numbers have significantly increased (see Figure 1).

|

|

||

|

Experts from the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs estimated that before the Czech Republic joined the EU in May 2004, between 30,000 and 40,000 Czechs worked legally abroad, mainly in Western Europe and the U.S.. According to the Czech Statistical Office, about 23,000 Czech citizens sent remittances in 2003; the value of those remittances is not known.

"Push" and "Pull" Factors

Today, there are no strong political or economic "push" factors that would prompt large numbers of Czech citizens to seek a better life elsewhere. The current unemployment rate is on par with other EU Member States — between eight and 11 percent, depending on which methodology is used. Although living standards lag those in Western European countries, the difference is not tremendous and has been diminishing over time.

Migrants have been attracted to the Czech Republic because of its strong labor market and because foreigners are easily able to find jobs. In 2004, there were 173,000 immigrants in the country who held work-related permits, 62 percent for temporary working and 38 percent for doing business in the country (the latter is easier to obtain, however). A third of the economically active foreigners are in Prague.

The structure of the Czech economy allows illegal and quasi-legal migrants to find work in the country. Despite attempts to change the situation by making employment regulations stricter, it is still possible to work without permission.

Immigrant Numbers Today

Of the 254,000 legal immigrants in the Czech Republic in 2004, about 60 percent were economic migrants, meaning they possessed a visa for a stay of over 90 days mainly for the purpose of employment, renewable on a yearly basis. The remaining 40 percent were those who came because of family reunification or family creation (under the umbrella of permanent residence), or, in the case of EU citizens, simply those who asked for permanent residence. These categories provide a basic typology of the country's legally registered foreigners.

The main countries of origin were Ukraine (78,263), Slovakia (47,352), Vietnam (34,179), Poland (16,265), Russia (14,743), Germany (5,772), Bulgaria (4,447), and Moldova (4,085).

In addition to Germany, legal immigrants came from the following Western countries: the U.S. (3,750), Austria (2,080), the UK (1,813), France (1,362), Japan (994), the Netherlands (923), Greece (792), and Canada (571). These migrants tend to be temporary and are either students or are concentrated in prestigious government and private-sector jobs, serving as government advisers, university professors, secondary school or private teachers, managers, small business owners, etc.

People from Ukraine had the most work permits (22,052) in 2004, followed by Bulgarians (1,617) and Mongolians (1,581). Vietnamese dominated the business-related permits with 22,046, followed by Ukrainians (19,486) and Slovaks (8,757). Currently, about one-third of foreign employees work in manufacturing and more than one-fifth in construction. With the exception of Westerners, most foreign workers are in manual, unskilled, and underpaid jobs.

In terms of permanent residents, in 2004 there were 20,689 from Vietnam, 16,976 from Slovakia, 13,262 from Ukraine, and 11,511 from Poland. Permanent residents are generally those who have married Czech citizens, economic migrants who have lived in the country for a long time and have successfully integrated into society, or immigrants from EU countries who have asked for permanent-resident status.

Until recently, Slovaks, due to a shared history, had specific migration privileges in the Czech Republic. For example, Slovaks did not need work permits; they only had to register their jobs. As a result, there are more Slovaks in the Czech Republic than are represented in the statistics of legal foreigners. Since the Czech Republic and Slovakia joined the EU in 2004, Slovaks have had the same rights as other European Union citizens to live and work in the country.

The Vietnamese presence in the Czech Republic is the result of a specific form of international aid available to communist countries during the communist era. Within this program, Vietnamese were invited to the Czech Republic as early as the 1970s and 1980s. Since then, new Vietnamese immigrants have arrived via social networks with Vietnamese already established in the country.

Although not a traditional asylum country, the Czech Republic faces an increasing number of asylum seekers. Between 1999 and 2004, 77,330 foreigners asked for asylum in the Czech Republic, and 2,567 of them (3.3 percent) were granted asylum.

In 2004, 5,459 people filed asylum applications, a significant decrease from the 11,400 applications filed in 2003. The main reason for the decline is that the Czech Republic, along with seven other Eastern European countries, joined the European Union on May 1, 2004. As of that date, the Czech Republic began returning asylum seekers, in accordance with the Dublin Convention, to the first EU country they entered.

In the case of Chechen asylum seekers, most have been returned to Poland, their first entry point in the EU. Since the Czech Republic's accession to the EU, Chechens have changed their strategy, and fewer than before now make use of the country's asylum channel.

The largest number of asylum applications in 2004 came from Ukraine (1,600), followed by Russia (1,498), Vietnam (385), and China (324). Since 2000, the country has also received asylum applications from people fleeing India, Romania, Afghanistan, and other former Soviet-bloc countries.

Ukrainian asylum seekers compose the most important ethnic group among asylum seekers who asked for asylum during the last decade. They consider the Czech Republic a destination country, in contrast to others who often misuse the asylum channel while trying to move west.

In 2004, 39 percent of asylum applications (about 2,100) were dismissed because the applicant attempted to illegally cross from the Czech Republic, mostly into either Germany or Austria. From the government's point of view, an applicant who disappears before a decision is made and is then caught trying to leave the country has made it clear that the intention was never to gain political asylum in the Czech Republic.

The illegal migrant population is sizeable, with estimates ranging from 300,000 to 340,000. In 2004, 9,433 foreigners were caught trying to illegally enter or leave the country. Of that number, 3,725 were Russians and 1,009 were Chinese. Many were likely being smuggled or trafficked to other countries in Europe.

Early Migration Policy

In the early 1990s, the Czech Republic passed migration-related legislation that policymakers modeled on legal principles in other democratic, developed countries. Yet the policies and practices adopted for regulating the entry and presence of economic migrants were far more liberal than those of most developed countries since Czech policymakers believed it was better to be quick than thorough and slow.

A number of readmission agreements concerning asylum seekers, as well as some multilateral and bilateral agreements for the employment of foreigners, were signed. Also, cooperation with international institutions dealing with migration was established. Furthermore, the introduction of a state integration program for refugees, return migrants, and some other specific categories of migrants was relatively effectively and successfully implemented.

Nevertheless, the migration policy did not work well in practice because there were no control mechanisms. No general goals were defined, and there were no specific preferences made regarding the economic, demographic, cultural, and geographic backgrounds of migrants.

At the time, however, it must be said that migration issues were not the primary concern. The government faced numerous other tasks and challenges related to the transition from communist to democratic rule.

Migration Policy Today

In 2002, the government set out six goals for migration policy and practice. These can be summarized as:

- respect EU rules and strategies while also acknowledging a governing role of the state in the migration process;

- coordinate activities of all state bodies and involve a wide array of nongovernmental and other civil-society organizations when implementing migration policy;

- eliminate all forms of illegal/irregular migration and other related illegal activities;

- keep the door open to legal migration by not imposing restraints; support immigration that is an asset for the state and society in the long term;

- involve nongovernmental and other civil-society organizations in order to implement migration policy; and

- contribute to solving migration problems at a global level.

So far, the Czech government has anticipated the changes necessary to make Czech law compliant with EU-level migration standards. The national agenda is clearly focused on illegal and transit migration and, to a lesser extent, on attracting high-skilled workers.

Regarding the integration of permanent or long-term immigrants, the government calls for fair treatment in many spheres of life.

The integration of the Roma population, many of whom face open discrimination and hostility, is complicated and burdened with negative experiences from the communist era, when the government attempted a mandatory assimilation program that failed. Solving these particular integration issues will require long-term, effective cooperation between the Roma and the majority population.

Some of the major issues in more depth:

Border Control, Illegal Migration, and Trafficking

As of its accession in May 2004, the Czech Republic became an interior country of the EU, rather than its previous status as a buffer zone that directly bordered the EU.

Although the country has most of the standard, EU border-control processes in place, combating illegal migration, its related employment and business activities, and trafficking will likely require stricter controls, new laws, and amendments to existing laws.

Another solution would involve addressing the country's demand for low-skilled workers. If a possible plan to issue temporary work permits to Ukrainians goes through, about 200,000 Ukrainians would be affected, including those currently employed illegally.

The country has already stepped up its anti-trafficking measures, strengthening legislation in 2004 and expanding a victim-assistance program into a nationwide, government-funded program. The Czech police now have more resources to investigate and convict traffickers, though sentences remain weak.

Deportation measures will probably also become stricter in the coming years. In 2004, 2,168 foreigners were sentenced to deportation, 694 of whom (32 percent) the government removed. The majority were expected to leave the country voluntarily.

Labor Migration

As in many other European countries, the Czech Republic's population is aging due to low fertility and rising life-expectancy rates. The government strongly believes immigrants will help solve the need for more workers and is actively trying to recruit a skilled, foreign labor force.

In July 2003, the government launched a pilot program to bring foreign experts, specialists, and other highly skilled workers, as well as their families, to the Czech Republic. Called "The Active Selection of Qualified Foreign Workers," the program operates on a point system that assesses a candidate's present employment, work experience, education, age, previous experience in the Czech Republic, language ability, and family members. Accepted candidates may qualify to receive a permanent residence after just 2.5 years.

The government first targeted potential immigrants from Kazakhstan, Croatia, and Bulgaria. Since October 2004, would-be immigrants from Belarus and Moldova, along with fresh graduate students from Czech universities from any country (except those who received a scholarship from the Czech government), have been allowed to participate.

As of July 1, 2005, citizens of Serbia and Montenegro and Canada are eligible; Ukrainians will be able to apply beginning in January 2006. In addition, the government has made it easier for previous foreign graduates from Czech secondary schools and universities to participate. Around 2008, the program is expected to be open to people from most countries.

Between the program's launch and April 2005, 279 people entered through the program, the majority of them Bulgarians in technical professions, the IT sector, health sector, and research/science. In addition, most of those accepted were already living in the Czech Republic when they applied.

Thus far, the program has failed to attract the number of applicants expected. Part of the problem is that would-be applicants have a difficult time finding a job and arranging a temporary work visa, prerequisites for applying to the program.

Also, few potential employers have been involved in the program, even though they need high-skilled workers. Furthermore, for the time being the government has opted to limit the potential pool of workers to a handful of countries, excluding such countries as India and China.

Asylum

In 1990, Czechoslovakia acceded to the 1951 Geneva Convention on Refugees and the 1967 Protocol, and, in 1993, the Czech Republic reaffirmed its accession following the split from Slovakia.

The Asylum Act of 2000, which gave many benefits to applicants, allowed asylum seekers to work as soon as they had filed their applications. But because of an increase in applications in 2001, the government passed an amendment in 2002 that introduced more restrictions. These included a ban on working legally for the first year of the asylum procedure.

Currently, the government is more concerned with economic migration than asylum. The country has benefited from the experiences of other EU Member States — Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, France, and others — in learning how to manage an asylum system. While the government is still in the process of harmonizing asylum procedures with EU standards, in general the system provides a level of service on par with other EU countries.

However, the current system could be strained if the number of asylum seekers were to dramatically increase.

Migration Policy and EU Membership

To join the European Union, the Czech Republic needed to strengthen migration control and to ensure it treated migrants according to EU standards and requirements.

The largest shift occurred via Act No. 326/1999, on the Stay of Aliens on the Territory of the Czech Republic (Aliens Act) and Act No. 325/1999, on Asylum (Asylum Act). Both acts passed in 1999 and entered into force in January 2000.

One of the most important changes was in regards to third-country nationals. Those who intend to come to the Czech Republic for a specific purpose, such as employment, now must first obtain a visa in their country of origin through Czech embassies or consular offices. Also, a new complex visa regime that contains provisions for the issuance, validity, and types of visa has been established.

In the last five years, several amendments to these acts have been adopted. Regarding the Asylum Act, the latest Amendment (No. 57/2005) transposes European asylum regulations into Czech law. These include minimal standards to apply when accepting asylum seekers, a right to family reunification, and criteria to decide which EU Member State is responsible for handling an asylum application. Due to a necessity to transpose other EU Directives relevant to asylum issues, more asylum-related amendments will have to be adopted soon.

The latest amendment to the Aliens Act's, passed in 2005, reflects the EU "Directive on Family Reunification of Third-Country Nationals," which protects the fundamental right to family life. The amendment makes conditions for migrants and unaccompanied minors who stay in deportation centers more "humane."

The amendment also stipulates that foreigners residing in the country must have health insurance; this requirement readies the Czech Republic for joining the Schengen Agreement, which permits non-EU nationals to travel freely within any EU country after receiving a visa from one of the Schengen countries. In addition, foreigners who would like to run their own business will be required to prove they have paid for the required insurance and taxes. Business employing illegal migrants will be charged for the cost of that migrant's deportation.

Thanks to the EU directive on family reunification, amendments to the laws on employment (No. 435/2994 Coll.) and small business (No. 455/1991 Coll.) are on the agenda, too. Thus, for example, the number of foreigners permitted to live in one apartment (measured in square meters) is now regulated.

Other amendments necessary for the transpositions of other directives are being prepared. These include directives on long-term residents, residence permits for victims of trafficking and smuggling, and the admission of students. In regards to the directive on long-term residents, the waiting period for a permanent residence permit is to be shortened from the existing 10 years to five years.

The next important step will be joining the Schengen Agreement. The Czech Republic should be able to meet all EU demands for Schengen membership by October 2007.

EU-Related Migration

As of May 2004, citizens of all EU countries are entitled to freely work in the Czech Republic under the same laws that protect national workers. The number of permanent residents from "old" EU Member States increased in 2004, mostly at the expense of long-term/temporary stays.

In absolute terms, however, the figures for EU citizens are not very high. Between December 2003 and December 2004, the number of Austrian permanent residents went from 787 to 1,068, British from 505 to 833, and German from 2,670 to 3,530.

Similarly, the same trend was visible in relation to Slovaks (11,499 versus 16,976), who, as already mentioned, had special migration privileges before both countries joined the EU.

Slovak immigration to the Czech Republic includes Slovak Roma, who have strong social ties to the Roma in the Czech Republic. Indeed, just after World War II and in the 1960s there were organized migration waves of Slovak Roma to the Czech Republic. It is estimated that in the beginning of 2000, between 10,000 and 14,000 Roma came to the Czech Republic from Slovakia.

Mobility for Czech Nationals

Before the accession of eight new post-communist Central/Eastern European countries to the EU on May 1, 2004, many existing EU Member States, particularly Germany and Austria, made it clear they did not want accession-state nationals to "flood" their labor markets.

The temporary barriers to labor mobility have meant that Czech nationals still need a work permit in all EU Member States except for Ireland, the UK, and Sweden, which all have kept their doors open to accession-state nationals. The UK and Ireland, bowing to concerns that thousands of Roma would come just for social benefits, decided to deter supposed "welfare migrants" by restricting benefit access.

Data on Czechs in the EU is very difficult to gain. So far, one may deduce that only a very limited number of Czechs have migrated and started working in countries that have allowed them to do so. It is estimated that between May and December 2004, some 3,000 Czechs registered in Ireland.

Issues on the Horizon

While the present coalition government, led by social democrats, has a pro-immigration stance, few political parties express their views on international migration issues. Accordingly, migration is not a priority and, in fact, has not yet been a high priority for political elites.

Nevertheless, media coverage has recently heightened public awareness, and attitudes towards the government's policies and practices have become more crystallized. As opinion polls show, most people in the Czech Republic oppose immigration, and if they accept immigrants, they prefer assimilation to the multicultural model. In this regard, it is clear that any governmental programs and policies that can be considered pro-immigration will have to be convincing and well-founded.

In the near future, the government should define and specify its "main migratory vision" — its economic, demographic, but also cultural and social diversity goals — and clearly link them to immigration and the country's needs and EU obligations.

As more people settle in the Czech Republic, the government will also need to refine its integration policies and practices. High-quality language and culture courses for new arrivals, common in many European countries, might be one approach.

The larger question is still how to effectively combat illegal migrants who come to work while simultaneously making use of their human capital. In addition, the government will have to more intensively and systematically address and combat discrimination, xenophobia, and racism. So far, the majority of Czech people are not ready to accept immigrants as equals.

Sources:

BARŠOVÁ, A.: Integrace přistěhovalců v Evropě: od občanské integrace k multikulturalismu a zpět? Příspěvek přednesený na konferenci Soudobé spory o multikulturalismus a politiku identit, 24. ledna 2005.

Czech Republic, Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2005). "Plans to introduce temporary work permits for Ukrainians." June 15. Available online.

DRBOHLAV, D.: Immigration and the Czech Republic (with a Special Focus on the Foreign Labor Force). International Migration Review, Vol. 37, 2003, No. 1, pp 194-224.

DRBOHLAV, D.: Migration Trends in Selected EU Applicant Countries; Volume II – The Czech Republic; "The Times They Are A-Changin". (European Commission Project: "Sharing Experience: Migration Trends in Selected Applicant Countries and Lessons Learned from the New Countries of Immigration in the EU and Austria). Vienna, International Organization for Migration (IOM) 2004.

BENEŠ, Z. et al.: Rozumět dějinám. Vývoj česko-německých vztahů na našem území v letech 1848-1948. Praha, Gallery 2002.

KUČERA, M.: Populace české republiky 1918-1991. Praha, česká demografická společnost, Sociologický ústav AV čR 1994.

KRIŠTOF, R.: Závěrečná zpráva k projektu Analýza soudobé migrace a usazování příslušníků romských komunit ze Slovenské republiky na území české republiky – pro odbor azylové a migrační politiky MV ČR. Praha, IOM 2003.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2004). "Background Note on the Protection of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in the Czech Republic." Regional Office for the Benelux and European Institutions. Available online.

Zpráva o situaci v oblasti migrace na území české republiky za rok 2004, 2005. Praha, MV ČR 2004, 2005.