You are here

Dependent on Remittances, Tajikistan’s Long-Term Prospects for Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction Remain Dim

With one out of every three working-age men abroad, the agricultural workforce in Tajikistan is overwhelmingly female. (Photo: Luigi Guarino)

Driven by a lack of economic opportunities in a Central Asian country of approximately 9 million people, more than 1 million citizens from Tajikistan travel to Russia for work each year, according to the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs. But the actual number of Tajiks in Russia may be much higher, with as many as 40 percent working illegally and therefore not appearing within the official statistics. Surveys indicate that 30 to 40 percent of households in Tajikistan have at least one member working abroad. Only a handful of other countries have a greater reliance on remittances than Tajikistan.

The poorest of the former Soviet republics, Tajikistan experienced a devastating civil war following its independence in 1991, which left more than 20,000 dead and a significant number displaced during the fighting (1992-97), with estimates ranging from 500,000 to 1.2 million. In addition, between 60,000 and 75,000 Tajiks fled to Afghanistan. Devastated by the twin shocks of post-Soviet transition and civil war, Tajikistan’s economy contracted by 60 percent in the first five years of independence. It took until 2006 for the economy to return to the same size as it was pre-independence. Today, more than two decades after the conflict’s end, enduring poverty and instability, limited agricultural and industrial production, low wages, and a deeply corrupt economic system have contributed to Tajikistan’s rise as a major exporter of labor as a substitute for domestic production of goods or services.

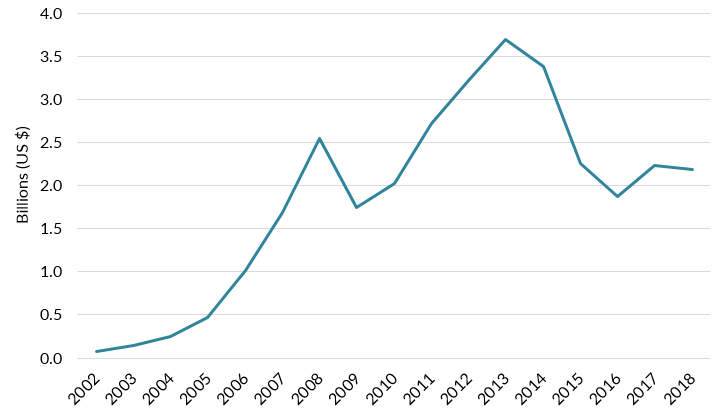

Migrants have become the country’s prime export and the single largest source of income. Remittances amounted to nearly half of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2013, according to the World Bank. This flow decreased following the collapse of the Russian ruble in December 2014 and ensuing economic crisis in Russia, with remittances representing the equivalent of 30 percent of GDP, or US $2.2 billion, in 2018. This fall in the value of remittances has created economic problems for Tajikistan, contributing to shrinking growth (from 7.4 percent in 2013 to 4.2 percent in 2015), slower poverty reduction, and a liquidity crisis within the banking sector.

Even as remittances have been a central pillar for Tajikistan’s economy, Russia has benefited greatly from Tajik migrants. Labor shortages and population shrinkages have pushed the country to accept foreign workers. According to official statistics, Tajiks made up one-fifth of labor migrants arriving in Russia in 2018. However, Russia has not developed a cohesive, consistent migration policy, and coupled with poor living conditions and xenophobia, life is difficult for Tajiks. Nevertheless, migration has come to define the relationship between Tajikistan and Russia. This article will explore challenges faced by Tajik migrants in Russia and the impacts such significant levels of emigration have on Tajikistan.

Life for Tajiks in Russia

Russia is the destination for more than 90 percent of Tajik foreign workers, sharing with Tajikistan a lengthy history of interaction, including regular flight connections, visa-free travel, a significant Tajik diaspora community, and many of the migrants having some degree of competency in Russian. Tajik workers are driven by lack of employment opportunities at home and higher wages in Russia, which are on average six times the monthly average income of workers in Tajikistan. Most migration is seasonal, with Tajiks traveling to Russia for work in spring and summer then returning home.

Figure 1. Map of Tajikistan and Russia

Source: Wikimedia Commons, “Russia Tadzhikistan Locator,” accessed October 31, 2019, available online.

Migration from Tajikistan is overwhelmingly male-dominated—one in every three working-age men in the country is abroad. However, women now make up an estimated 18 percent of migrants. Tajik migrants are also young, with half between ages 18-35. Most engage in semiskilled or unskilled professions in Russia, with construction accounting for more than half of jobs. Other sectors include retail, household services, agriculture, and transportation.

Drawn by employment opportunities, half of all Tajiks in Russia live in Moscow and its surrounding regions, often in squalid, overcrowded conditions. Russia’s economic crisis and the ruble’s devaluation have led to a significant reduction in income for Tajik workers. Meanwhile, the cost of housing, food, and work permits (known as patents) has increased, leading to a fall in the value of remittances. In addition, in 2016, the National Bank of Tajikistan changed regulations on foreign exchange transactions, forcing migrants to send money back in the national currency, the somoni. Given that the exchange rate was weak, the value of remittances fell. Many Tajiks working abroad have responded by sending cash back informally, through friends and relatives going to Tajikistan.

Migrants Wanted, But Russian Policies Are Becoming More Strict

With its population aging and expected to shrink by 2.5 million people by 2035—and the labor force predicted to contract by 10 million people—Russia requires foreign workers to fill jobs and develop its economy. With a foreign-born population of about 12 million, Russia had the world’s fourth largest immigrant population in 2019. Despite this reliance on immigration, Russia has not developed a consistent migration policy, oscillating between permissive and restrictive policy regimes, both of which have been unevenly implemented. This is largely due to competing needs of placating a widely xenophobic population, while addressing the country’s very real labor shortages. But it is also linked to corruption. Migration management is selective in order to ensure that a large number of migrants remain in the informal labor market, generating a steady stream of bribes.

Recently, Russia has implemented more restrictive policies targeting immigrants from outside the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU)—including Tajikistan—as a way to pressure the country to join the EEU, where regulations for citizens of member states are more lax. While the incentives for Tajikistan to join the Russian-led economic bloc are mostly related to easing restrictions on migration, for Russia, Tajikistan’s membership would draw the country further under its influence.

Regulations introduced in 2015 (at the same time Kyrgyzstan joined the EEU) required that non-EEU migrants from the former Soviet Union register within 15 days of arrival and then apply for a one-year work permit one month after arriving. Not all who enter for the purpose of work receive a patent. In 2017, 4 million foreign workers entered and just 1.9 million patents were issued, indicating that a large number are working illegally in Russia. In addition, the 2015 reform introduced language, history, and culture tests for foreigners. It also ended the practice of allowing Tajik citizens to enter Russia on internal Tajik passports, a holdover from Soviet days. Further changes in June 2018 compel migrants to register at their place of residence, not work, and reduced to seven days after arrival, from 15, the deadline by which foreigners should register. These changes increase the likelihood of migrants breaking the regulations and place the burden on landlords, many of whom are unwilling, to file paperwork to register foreign nationals—leading to many foreigners paying bribes to be registered.

For migrants already present in Russia or intending to make the journey again, the country has made re-entry more difficult in recent years. In 2013, the Russian government introduced a re-entry ban for those who had committed two or more administrative violations (administrativnie narusheniia) ranging from driving without a license to smoking in no-smoking zones, jaywalking, or overstaying an earlier visa. The list of those banned from Tajikistan alone grew to 400,000 before a 2017 deal with Tajikistan secured the removal of 100,000 names from the list. Currently, there are an estimated 240,000 Tajiks who are unable to travel to Russia. Although the data are publicly accessible, many Tajiks are unaware they are banned until they attempt to travel to Russia. Between 2017 and 2018, 60,000 Tajiks were deported. Immigration hearings in a Moscow court witnessed by the author involved up to five individuals at a time, with less than two minutes spent per migrant.

Other Obstacles

In addition to navigating tightening regulations, many Tajiks face societal discrimination and abuse in Russia. As in other parts of the world, foreign workers are viewed as an economic threat, accused of taking jobs from Russian citizens. Those from majority-Muslim Tajikistan are also viewed as a societal threat, undermining Russian culture and national identity by contributing to the Islamization of Russia. Finally, they are perceived as a security threat, linked to drug trafficking, terrorism, and organized crime. A 2018 Russian Public Opinion Research Center (WCIOM) poll indicated that 51 percent of respondents thought crime was increasing due to immigrants. In fact, official statistics indicate that the migrant crime rate is lower than average, with the foreign born committing just 3.5 percent of crimes in 2012 while representing nearly 8 percent of the overall population.

According to the Russian polling center Levada, hostility towards foreigners reached a peak in 2013, at the same time record numbers of Central Asian migrants were present. Then, 81 percent of Russians supported restrictions on immigration. Today, the figure stands at 71 percent. A 2016 WCIOM survey found that more than half of respondents thought that “there are a lot of or too many migrants in their area.” Two years later, a WCIOM poll found that only one-fifth of respondents supported easing restrictions on migration from the former Soviet republics.

Ill feelings surge during terror attacks, with blame placed on Muslim migrants from Central Asia and Muslims from the North Caucasus. Following the 2013 murder of a young ethnic Russian, anti-immigrant riots engulfed the Moscow suburb of Biryulyovo, resulting in hundreds of arrests. Politicians from both the government and opposition often appeal to anti-foreigner sentiment. In 2017, for example, Deputy Prime Minister Olga Golodets accused migrants of undermining the development of Russia by having “low qualifications and being a burden for social services with their families needing education and care.” Opposition leader Alexei Navalny has made several derogatory remarks about immigrants and supported moves to tighten restrictions on migration.

Despite xenophobic rhetoric, however, instances of racially motivated hate crimes have decreased in recent years from a peak of 603 incidents in 2007 to 56 in 2018, according to data collected by the SOVA Center. Two developments help explain this decrease. First, the Russian government has sought to co-opt and control discourses on Russian nationalism, purging it of some its more extreme elements, in what Luke March has called “managed nationalism.” In the wake of the so-called color revolutions (a series of movements in former Soviet countries during the early 2000s) and the mass demonstrations during the winter of 2011-12 in Russia, the government of Vladimir Putin acted to exert control over nationalist movements, utilizing them to pursue regime goals and suppressing them should they become a threat to stability. Second, Russian nationalists have been distracted by the ongoing conflict in Ukraine and occupation of Crimea.

Beyond hostility, Tajiks, who often have only a basic command of the Russian language, may also face problems with law enforcement: spot document checks by police represent an opportunity for extortion. In addition, foreign workers may be exploited by employers, who often cheat them of their wages, sometimes physically abuse them, or force them to work without pay.

For many Tajiks, practicing Islam helps them cope with life in Russia, providing a sense of solidarity and community. Where Islamic practice is severely curtailed by the government in Tajikistan—for example, young people and women are not permitted to pray in mosques and there are no Islamic religious schools except for one Islamic university—Russia offers an environment where migrants can explore their religious identity more freely, despite occasional Islamophobia.

Emigrants Are a Necessary, Yet Potentially Volatile, Social Group

Migration is the single most important external source of income for Tajikistan. Remittances have been a major engine of economic growth for more than ten years: as remittances have risen, economic growth has increased, and the poverty rate has halved since the start of the century.

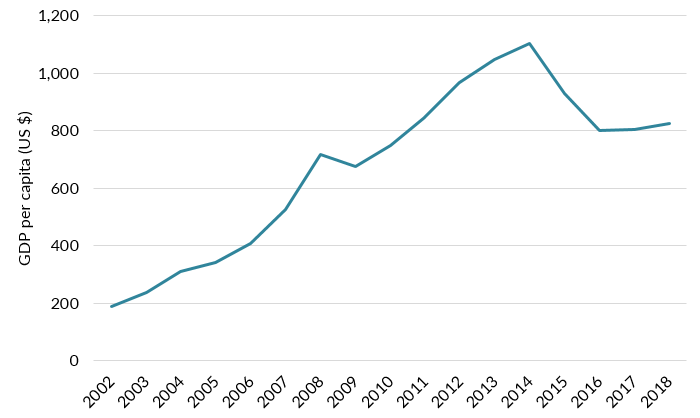

Figure 2. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per Capita in Tajikistan, 2002-18

Source: World Bank, “GDP per capita (current US$) – Tajikistan,” accessed November 11, 2019, available online.

And yet, dependence on migration has made Tajikistan’s economy vulnerable to exogenous shocks. Remittances fell dramatically in 2009 following the global economic crisis, recovering their value in 2012, only to fall again after the Russian ruble collapsed in late 2014 as a result of plummeting oil prices and Western sanctions imposed subsequent to the invasion of Crimea. By the end of 2015 the actual value of transferred funds from Russia to Tajikistan had halved, resulting in inflation and a liquidity crisis within the Tajik banking sector. Further, the fall in the value of remittances has led to a slowing of the poverty reduction rate, according to the World Bank.

Figure 3. Remittances to Tajikistan, 2002-18

Source: World Bank, “Personal remittances received – Tajikistan,” accessed November 6, 2019, available online.

Led by President Emomali Rahmon (who has been in power since 1992), Tajikistan is an authoritarian state that has never held a free and fair elections. Although government officials almost never publicly acknowledge the key role migration plays in the economy, they do benefit from it politically. The departure of working-age men—and some women—forms a safety valve, allowing the country to export excess labor and preventing them from staying to grow further discontented with the regime. At the same time, Tajik migrants are viewed as a potential threat to the regime, which perceives Russia as a space where Islamic extremist organizations and domestic opponents in exile can more easily recruit individuals to the opposition. As such, the government has taken steps to minimize the voice that migrants can exercise.

For example, while domestic turnout for the 2015 parliamentary election was claimed to be 88 percent, the government made few accommodations to allow its diaspora to vote. It arranged for just three polling stations in Russia, to accommodate nearly 1 million Tajiks, who represented 25 percent of the electorate. This was a marked decline from the 2013 presidential election, when the government provided 24 polling stations in Russia.

Although the Rahmon regime views the diaspora as a potential threat, it has taken steps to develop policies to help support emigrants before departure. In 2010, the government established the Tajik Migration Service, based on recommendations from the International Organization for Migration (IOM), among other civil-society organizations. At the same time, it published a strategy on labor migration, which envisages providing professional training to its nationals before their departure. Diaspora associations have been established in Russia to provide free legal assistance to Tajik migrants. But there remains a lack of mechanisms to facilitate migrant return, reintegration into the domestic job market, and investment in the local economy.

While migration offers Rahmon a key tool to keep power, it also gives Russia tremendous influence over Tajikistan. In 2011, when Russian pilot Vladimir Sadovnichy was detained by Tajikistan and accused of smuggling aircraft parts, Russian authorities responded by detaining hundreds of migrants. Some State Duma deputies demanded that Russia introduce visa requirements for Tajik nationals. The Rahmon government quickly backed down and released the pilot. But the specter of Russia sending back thousands of migrants to a domestic market that has little capacity to absorb them still haunts Tajikistan.

Socially, one of the major impacts of mass migration is absence. One survey found that 30 percent of Tajik households had one member who had migrated, leaving children to be cared for by their mothers or grandparents. Traditionally, women are responsible for family care and do not work outside the home, relying on income generated by their husbands and children. Yet this is changing. The lack of men in the summer months has led to an increasing feminization of agriculture, the female share of the agricultural labor force increasing from 59 percent in 1999 to 75 percent today. The strain placed on families by long-term migration has also contributed to family breakdown, with some men divorcing their wives and remarrying in Russia. Divorce rates doubled between 2005 and 2010, according to the Tajik government. With a shortage of men, polygamy is becoming more commonplace even though it is illegal.

Disincentivizing Leaders from Investing in Tajikistan’s Future

In the long term, emigration will bring more harm than good to Tajikistan’s economy. Migration has been a lifeline for the Tajik population, providing a means for households to survive and, in some cases, lift themselves out of poverty. Yet very little of the capital accumulated through migration is re-invested in Tajikistan in ways that help the domestic economy develop beyond assisting individual households. According to survey data, more than 80 percent of remittances go towards essential household consumption such as food, clothes, weddings, education, and maintenance.

To be sure, remittances play an important role in improving life for Tajiks. Still, these money transfers could play a more significant role in economic growth and job creation, provided that the major portion is channeled into developing small and medium enterprises. Yet most households do not have enough disposable income to dedicate to investments. And those hoping to start their own business face serious challenges. Tajikistan’s business sector is deeply corrupt and dominated by members of the president’s family, who use their links to the levers of power to extort money from successful entrepreneurs. The country’s tax system is also prohibitively complex. As such, the government has yet to create favorable conditions for the investment of remittances, in fact creating a hostile environment. Its National Development Strategy for the Period up to 2030 places emphasis on diversifying emigrant destinations beyond Russia and developing programs to protect worker rights abroad but does not outline any strategies to make remittances more productive.

Economically, while in the short term remittances have helped some households out of poverty, dependence on migration has led to stagnation, reducing incentives for the government to create programs to develop the domestic economy. Politically, migration renders Tajikistan dependent on Russia, forming an important tool through which the Kremlin can retain influence over the poorest former Soviet republic. Therefore, Tajikistan appears set to remain one of the world’s most economically migration-dependent countries in the decades to come.

Sources

Asia Development Bank. 2002. The Country Classification of Tajikistan. Available online.

Babagaliyeva, Zhanna, Abdulkhamid Kayumov, Nurullo Mahmadullozoda, and Nailya Mustaeva. 2017. Migration, Remittances, and Climate Resilience in Tajikistan. Almaty, Kazakhstan: Regional Environmental Center for Central Asia (CAREC). Available online.

Bahovodinova, Malika. 2016. Tajikistan’s Bureaucratic Management of Exclusion: Responses to the Russian Reentry Ban Database. Central Asian Affairs 3 (3): 226-48.

---. 2018. Representing the Social Costs of Migration: Abandoned Wives or Nonchalant Women. Central Eurasian Studies Society, the CESS Blog, November 12, 2018. Available online.

Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2018. Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018 Country Report – Tajikistan. Gütersloh, Germany: Bertelsmann Stiftung. Available online.

Bhutia, Samten. 2019. Russian Remittances to Central Asia Rise Again. EurasiaNet, May 23, 2019. Available online.

Cleuziou, Juliette. 2016. “A Second Wife Is Not Really a Wife:” Polygyny, Gender Relations, and Economic Realities in Tajikistan. Central Asian Survey 35 (1): 76-90.

Daly, John C. K. 2014. Russia’s New Passport Regulations Impose Additional Hardships on Tajik Migrant Workers. Eurasia Daily Monitor 11 (212). Available online.

Dodarkhujaev, Rahmonali. 2015. Tajik Labor Migration Boosts Divorce Rates. Institute of War and Peace Reporting, January 27, 2015. Available online.

Erlich, Aaron. 2006. Tajikistan: From Refugee Sender to Labor Exporter. Migration Information Source, July 1, 2006. Available online.

Eurasian Development Bank, United Nations Development Program (UNDP). 2015. Labor Migration, Remittances, and Human Development in Central Asia. Almaty, Kazakhstan: Eurasian Development Bank. Available online.

Golunov, Serghei. 2014. Dangerous Immigrants or Dodgy Perceptions? The Correlation between Immigration and Crime in Russia. PONARS Memo, 321. Available online.

Government of Tajikistan. 2016. National Development Strategy of the Republic of Tajikistan for the Period up to 2030. Available online.

Human Rights Watch (HRW). 2009. “Are You Happy to Cheat Us?” Exploitation of Migrant Construction Workers in Russia. HRW, February 10, 2009. Available online.

Ibañez-Tirado, Diana. 2019. “We Sit and Wait:” Migration, Mobility, and Temporality in Gulistan, Southern Tajikistan. Current Sociology 67 (2): 315-33.

International Labor Organization (ILO). 2010. Migration and Development in Tajikistan – Emigration, Return and Diaspora. Moscow: ILO. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2009. Abandoned Wives of Tajik Labor Migrants. Dushanbe, Tajikistan: IOM. Available online.

Kislov, Daniil and Ernest Zhanaev. 2017. Russia: Xenophobia and Vulnerability of Migrants from Central Asia. Foreign Policy Centre, December 4, 2017. Available online.

Laruelle, Marlene and Caress Schenk, eds. 2018. Eurasia on the Move. Washington, DC: The George Washington University, Central Asia Program. Available online.

Levada Center. Левада-центр о ксенофобии в 2019 году [Levada Center on Xenophobia in 2019]. Updated September 18, 2019. Available online.

Lipman, Maria and Yulia Florinskaya, 2019. Labor Migration in Russia. PONARS. Available online.

Maier, Alexander. 2013. Tajik Migrants with Re-Entry Bans to the Russian Federation. Dushanbe, Tajikistan: IOM. Available online.

March, Luke. 2012. Nationalism for Export? The Domestic and Foreign-Policy Implications of the New “Russian Idea.” Europe-Asia Studies 64 (3): 401-25.

Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Russian Federation. 2019. Selected Indicators of the Migration Situation in the Russian Federation for January-December 2018, with Distribution by Country and Region. Updated January 24, 2019. Available online.

Moscow Times. 2018. Xenophobia on the Rise in Russia, Poll Says. Moscow Times, August 27, 2018. Available online.

Mughal, Abdul-Ghaffa. 2007. Migration, Remittances, and Living Standards in Tajikistan. Dushanbe, Tajikistan: IOM. Available online.

Mukhamedova, Nozilakhon and Kai Wegerich. 2018. The Feminization of Agriculture in Post-Soviet Tajikistan. Journal of Rural Studies 57: 128-39.

Mukomel, Vladimir. 1997. Demograficheskie Posledstviia etnicheskikh i religional’nikh konfliktov v SNG. Naselenie & Obshchestvo 27 (April 1997).

Murakami, Enerelt, Eiji Yamada, and Erica Sioson. 2019. The Impact of Migration and Remittances on Labor Supply in Tajikistan. Working Paper No. 181, JICA Research Institute, Tokyo, January 2019. Available online.

Olimova, Saodat and Igor Bosc. 2003. Labor Migration from Tajikistan. Dushanbe, Tajikistan: IOM. Available online.

Popov, Dmitry. 2015. Трудовая миграция из Таджикистана в цифрах [Labor Migration from Tajikistan in Figures]. Russian Institute of Strategic Studies, May 29, 2015. Available online.

Radio Free Europe. 2007. Tajikistan’s Civil War. June 26, 2007. Available online.

Roche, Sophie. 2014. The Role of Islam in the Lives of Central Asian Migrants in Moscow. CERIA Brief No. 2, Central Asia Program, The George Washington University, October 2014. Available online.

Schenk, Carress. 2018. Russian Immigration Control: Symbol Over Substance. PONARS Policy Memo 518. Available online.

Troitsky, Konstantin. 2015. Административные Выдворения из России: Судебное Разбирательство или Массовое Изгнание? [Judicial Expulsions from Russia: Judicial Hearing or Mass Exile?]. Moscow: Civic Assistance Committee. Available online.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). 2011. Impact of Labor Migration on “Children Left Behind” in Tajikistan. Dushanbe, Tajikistan: UNICEF. Available online.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA), Population Division. 2019. International Migration 2019: Wall Chart. Accessed October 20, 2019. Available online.

Wikimedia Commons. 2008. Russia Tadzhikistan Locator. Accessed October 31, 2019. Available online.

World Bank. 2019. Tajikistan Country Economic Memorandum: Nurturing Tajikistan’s Growth Potential. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online.

---. N.d. GDP per Capita – Tajikistan. Accessed November 11, 2019. Available online.

---. N.d. Migrant Remittance Inflows. Accessed October 23, 2019. Available online.

---. N.d. Personal Remittances Received – Tajikistan. Accessed November 6, 2019. Available online.

World Politics Review (WPR). 2019. Russia Needs Immigrants but Lacks a Coherent Immigration Policy. WPR, May 14, 2019. Available online.