You are here

Following the Money: Chinese Labor Migration to Zambia

Many Chinese workers enter Zambia in supervisory roles on major infrastructure projects. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Ching Kwan Lee)

Chinese migration to Zambia has increased in recent years following the development of a strong economic relationship between the two countries, and against a backdrop of rising Chinese migration to resource-rich areas of the world. China has invested billions of dollars in Zambia’s most profitable industries, and is responsible for most major infrastructure projects in the country. In 2014 it also began funding Mandarin instruction in Zambian government secondary schools. Flows of people have begun to follow the flows of investment capital: the number of Chinese nationals entering Zambia has increased by 60 percent since 2009.

The design of Zambia’s immigration system and its migration relationship with China offer insight into the migration policies and trends of developing countries, providing a more nuanced view of migration flows worldwide. Prevailing migration theory largely applies to conventional flows of people from poorer to richer countries (known as South-North migration). The Chinese flow to Zambia, characterized by highly skilled migrants, exemplifies the phenomenon of South-South migration, which represents more than one-third of global migration.

This article examines the newly emerging migration pattern from China to Zambia, a nontraditional destination, based on original research including the author’s coding of more than 25,000 Zambian entry permits for 2012 and 2013 and in-depth interviews with key officials and community members. Though the Chinese population in Zambia has received much negative media attention, mainly due to the anti-Chinese rhetoric of late President Michael Sata, the Zambian government now largely recognizes the importance of the economic relationship. While integration of Chinese arrivals into Zambian society has been minimal to date, continuing Chinese investment suggests the population is only going to grow further.

The Zambian Immigration System

All visitors require a visa to enter Zambia, with stays past 30 days requiring an additional permit. The six major permit types are: residence, visiting, study, employment, temporary, and self-employment (investor). Permitted length of stay varies from three months to ten years, with employment permits lasting for two years. Zambia does not have a separate permit for family reunion—family members enter on the same permit as the initial holder. This complicates collection of accurate statistics, as only the individual granted a permit is written into the immigration records.

The Zambian government prioritizes migrants with high socioeconomic status, and does not intend to provide social welfare to new residents, as indicated by the following four tenets of Zambian immigration policy, which are that an immigrant to Zambia:

- must have a contribution to make in the form of skills, profession, or capital

- should not deprive a Zambian of employment

- should not be a charge on the state

- must be in possession of a permit.

Zambia is not a traditional migration destination; ranking 141 of 187 on the United Nations’ Human Development Index, it has not historically attracted many aspiring newcomers. It therefore serves as a useful counterpoint to frequently analyzed destinations such as the United States and the United Kingdom.

Migration in Developing Countries

Zambia offers a strong example of developing-country policies. Nontraditional destinations are often left out of migration studies, due to the continued focus on archetypal low-skilled migration to high-income countries. However, almost half of the world’s estimated 321.5 million international migrants reside in a developing country; 36 percent (82.3 million) were born and still reside in the global South. This figure exceeds all other geographic migration patterns and is therefore crucial to understand.

To accurately assess the impact of these South-South flows, one must first understand the main characteristics of the South-North archetype, which has been characterized as flows of “low-skilled and culturally distinct people from poorer countries [to wealthy countries], increasingly perceived as a problem in need of control,” according to migration scholar Hein de Haas. While many prospective migrants look for greater economic opportunity abroad, traditional migration destinations are also attractive for their relatively higher levels of safety, employment, and social services. Receiving countries typically employ strict entry rules including extensive border enforcement to keep out these lower-skilled newcomers.

In contrast, immigration to developing countries tends to be characterized by higher admission rates and individuals with more diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. Immigration policies in developing countries may not necessarily be less stringent than elsewhere, but the capability to strictly enforce borders is often lacking. Much South-South migration is therefore unauthorized; almost 80 percent is estimated to take place between countries with contiguous borders and limited procedural formalities. Though most countries welcome skilled migration, developing-country policies in particular favor the admission of better-educated individuals to help improve the domestic economy. The combination of these two characteristics leads to a diverse migration system.

Recent Zambian Migration Trends

The total volume of migration to Zambia is low, with approximately 16,500 permit applications submitted in 2011, the highest level in recent years. (It is also important to keep in mind that family members are admitted with the permit holder and not on their own separate permits; one permit thus does not necessarily equal one person.)

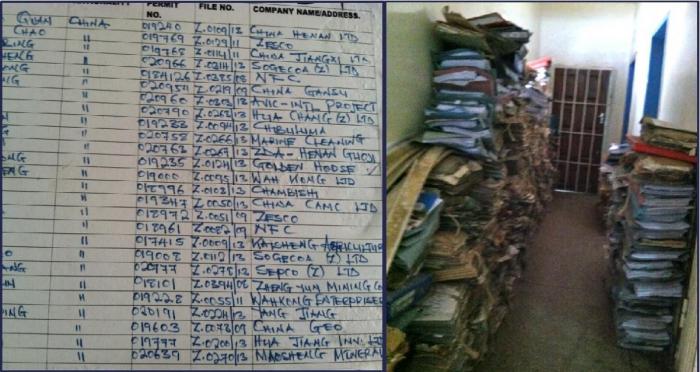

The author manually transcribed 25,000 Zambian immigration permits (Photos: Hannah Postel)

The author was granted access to employment permit data for 2012 and 2013 by the Zambian Department of Immigration, manually transcribing details from more than 25,000 permits. The 2012 records provided information on nationality, occupation, and employer of each permit holder. While the 2013 records did not include individual occupations, locational data were recorded for some of the permit-sponsoring employers, providing insight into patterns of residence in-country. The author also conducted interviews with Zambian government officials, Chinese government and industry representatives, and international organization staff. Total immigration numbers and important metadata for permit transcription were obtained from the Employment Permit Secretariat and Department of Immigration officials.

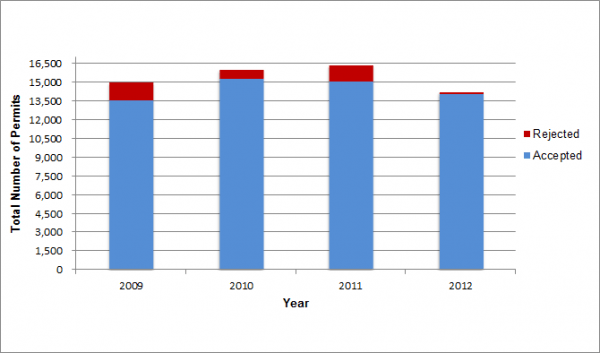

Zambia is quite open to foreigners: on average, just 5.8 percent of applicants were denied admission over the 2009-12 period surveyed (see Figure 1). Educated, investment-focused applicants were favored for their potential to contribute to the domestic economy.

|

Figure 1. Zambian Entry Permit Applications by Approval, 2009-12

|

|

Source: Zambian Department of Immigration, Immigration Permit Details (Lusaka: Department of Immigration), 2009-12. |

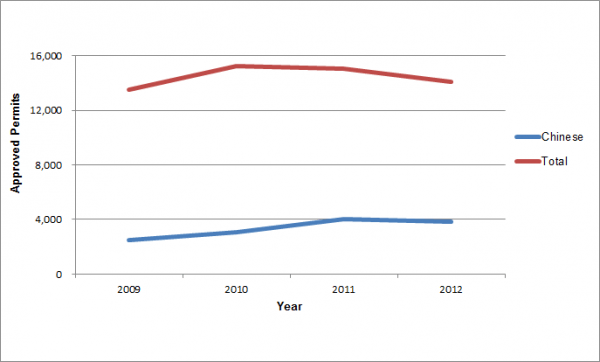

China, India, and South Africa supply the largest numbers of migrants to Zambia, followed by Zimbabwe, the United Kingdom, and the United States (see Figure 2). Migration to Zambia is diverse, with at least one-third of approved permits allocated to individuals from countries other than the top six senders.

|

Figure 2. Approved Permits by Nationality, 2009-12

|

|

Source: Zambian Department of Immigration, Immigration Permit Details. |

In general, the quality of official statistics is poor; this is especially true for exit records. Those leaving are supposed to turn in their permits and get their passport stamped upon exit; however, most people do not follow these requirements and it is unclear if exit stamps are recorded with any frequency. It is thus nearly impossible to determine either the overall size of the immigrant population or annual net inflows and outflows. Analysis of permit trends instead of short-term visa issuances focuses on migrants who indicate at least a three-month planned stay, but there is no way to know exactly how long permit holders remain in Zambia. Conversations with immigration officials and independent immigration consultants confirmed the impression that most permit holders from the United States and United Kingdom enter on short-term work permits and leave after the duration of their contract. Indians, South Africans, and Zimbabweans tend to migrate more permanently. Consensus on the Chinese was divided.

Though migrants from neighboring African countries (apart from those mentioned above) do not figure prominently in permit and visa data, this is likely because they do not enter Zambia through formal channels. Such data are collected manually and inconsistently at border posts, and there is no enforcement along the majority of the border. The Zambian government is largely unaware of the volume or characteristics of migrants crossing into the country informally, according to the Deputy Chief of Operations of the Department of Immigration. Though Somali and Congolese immigrants have built a sizeable community in Lusaka, Zambia is still mainly a transit point for Central and East African migrants traveling to South Africa; many do not choose to reside in Zambia permanently.

Chinese Migration to Zambia

Though Zambia has long been a hotspot for Sino-African economic relations, Chinese migration to the country remained minimal until 2008. Home to China’s first foreign aid project, the TAZARA Railway, Zambia also hosts China’s first operational “special economic zone” on the continent. As in much of Africa, China is responsible for most major infrastructure projects, and has invested billions of dollars—about 11 percent of Zambia’s estimated $26.8 billion in gross domestic product (GDP)—in copper mining, construction, and manufacturing. Chinese migration to Zambia exemplifies sociologist Stephen Castles’ statement that “migrations are not an isolated phenomenon: movements of commodities and capital almost always give rise to movements of people.”

The Chinese population in Zambia has been the focus of disproportionate media attention, largely due to late Zambian President Michael Sata’s infamous anti-Chinese platform in the 2006 elections. His alarmist claim of 80,000 Chinese residents in Zambia has pervaded coverage of the subject. The Chinese presence in Zambia has been continuously overstated due to this extreme overestimation. Others have previously suggested a population in the 4,000-15,000 range; a recent estimate conducted by the author using census and immigration data ranged from 5,000 to 18,000, with a likely center around 12,000-15,000. Even though developing a precise and accurate estimate is nearly impossible (due to unreliable statistics and high numbers of temporary migrants), it is important to maintain a sense of scale when discussing Chinese migration to Zambia. Even at a high bound of 18,000, the Chinese community represents just one-tenth of 1 percent of the Zambian population.

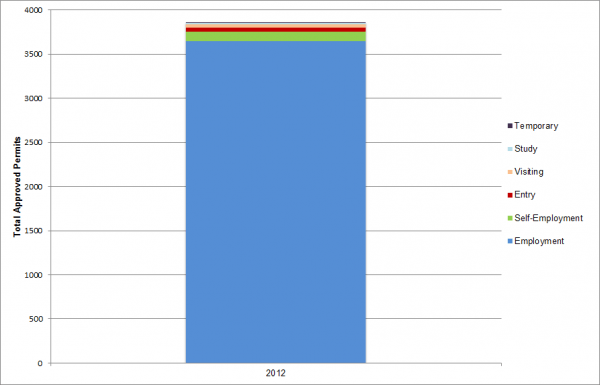

With this in mind, Chinese migration to Zambia has indeed increased in recent years. Figure 3 shows the number of approved permits for Chinese nationals against the total number of permits granted. Though the total number of Chinese entering the country decreased between 2011 and 2012, the percentage of permits granted to Chinese applicants has continued to grow. Approved work permits for Chinese immigrants jumped to 5,897 in 2013, according to a preliminary count. The overwhelming majority of Chinese move to Zambia to work (see Figure 4). Of the 9,067 total employment permits recorded in 2012, more than one-third (3,722) were granted to Chinese nationals.

|

Figure 3. Approved Entry Permits for Chinese and All Nationalities to Zambia, 2009-12

|

|

Source: Zambian Department of Immigration, Immigration Permit Details. |

|

Figure 4. Types of Zambian Entry Permits Granted to Chinese Nationals, 2012

|

|

Source: Zambian Department of Immigration, Immigration Permit Details. |

Roles and Integration of Chinese Immigrants in Zambia

Chinese migration to Africa is often categorized into three different types: temporary labor migrants, small-scale entrepreneurs, and transit migrants. The first category can be divided into two subgroups: semi-skilled laborers largely returning to China after completing their contracts, and a smaller group of managers and professionals often remaining in Africa as entrepreneurs. In her study of Chinese activities in Zambia, Solange Guo Chatelard also includes a “small number of expatriates sent over by central and provincial government agencies to fulfill diplomatic, managerial and consultant functions in different sectors.”

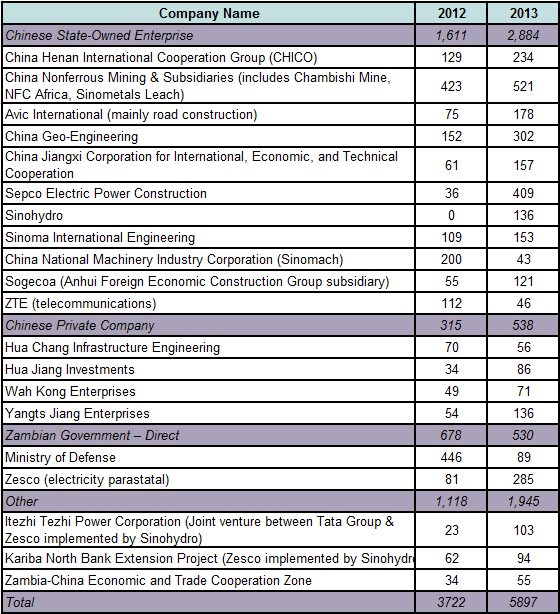

Quantitative evidence from Zambia largely supports these typologies. As shown in Figure 4, 95 percent of the Chinese entering Zambia in 2012 (3,722 permits) were labor migrants. All but a few were employed by Chinese-owned companies. National or regional Chinese state-owned enterprises sponsored 2,026 individuals. Zambian government ministries directly hired 678 Chinese, while many more were working on Zambian government contracts won by large Chinese construction companies (see Table 1). One particularly interesting example is the 446 individuals hired by the Zambian Ministry of Defense and Air Force. Though at first glance the possibility that Chinese nationals might be staffing Zambia’s military roster could be a cause for concern (especially given extensive media focus on the Chinese “takeover” of Africa), permit details show that most if not all of these individuals were working to build the new Air Force barracks on a government contract with the Chinese construction giant Sinomach.

|

Table 1: Zambian Employment Permits by Selected Companies, 2012-13

|

|

Note: Companies hiring smaller numbers of Chinese workers were not identified individually but are included in the totals for each category. Source: Zambian Department of Immigration, Immigration Permit Details. |

These figures illustrate how crucial government contracts are to the flow of Chinese labor migrants to Zambia. While not a single Sinohydro employee entered the country in 2012, this figure jumped to 136 in 2013 (direct employees; 333 when including their contract workers). The reverse is also true: while in 2012, 200 employees were hired by Sinomach and 446 by the contracting Ministry of Defense, after the project was completed the number dropped in 2013 to 43 and 89, respectively.

While the distinction between different categories of Chinese labor migrants to Africa largely holds true in Zambia, a number of Chinese managers said that staying in Zambia would end their careers. Personal connections are central to successful business networking in China and are impossible to maintain from such a distance. Those who do remain to begin their own companies often in turn hire more Chinese employees. For example, an individual granted an investor’s permit in 2011 to establish the company Camland Construction sponsored 11 work permits for Chinese migrant employees in 2013. It is likely that most of the migrants falling into the “other” category work for small Chinese-owned businesses (typically restaurants, import-export shops, and spin-off construction companies). Due to the imprecision of Zambian data and the degree of state influence on “private” Chinese businesses, it is impossible to determine the exact nature of many of these enterprises. However, after accounting for joint ventures and third-country corporations, among others, a conservative estimate of 60 percent of these “other” workers are in Zambia on small-time private interests. Chinese entrepreneurs accounted for 237 investment permits from January 2012 to June 2014. These new businesses were largely concentrated in the construction, manufacturing, and mining industries.

Chinese transit migrants are likely quite few. It is impossible to estimate the number due precisely to their transient nature and poor immigrant exit records, but a large majority of the Chinese community as observed and self-described either planned to remain in Zambia or return to China in the medium term.

Employment data on Chinese nationals in Zambia illuminate the economic and social role they play in-country. Many aspiring Chinese migrants fit Zambian immigration policy aims of admitting highly educated, investment-seeking foreigners to combat the local skills gap. This is demonstrated by extremely high admission rates: less than 1 percent of Chinese work-permit applicants were rejected in 2012. Coding for terms such as “manager,” “director,” and “senior,” 2,754 permit holders were identified in managerial occupations. Chinese nationals accounted for 923 of these managerial permits, entering Zambia to play a supervisory role.

Importing Chinese Labor

One of the most contentious aspects of the Chinese presence in Africa is Chinese labor imports. Many major Chinese companies are said to hire almost entirely from China to the exclusion of local workers, citing language and cultural differences. One of late President Sata’s major accusations in 2006 was that the Chinese “infesters” were taking jobs away from Zambians. The data support this claim to some extent: Chinese companies were the most likely to pad their employment rolls with individuals not necessarily bringing specific education and expertise to the table. Almost every large company hired at least one “Chinese chef,” while 628 permits (17 percent of the total) in 2012 were granted to people with vague titles like “constructor” and “skilled worker.”

Increasing Diversity

The Chinese population in Zambia shows that emigration from China is increasingly diverse. The typical Chinese migrant is no longer a 20- to 30-something male from coastal regions such as Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Fujian. Though no formal data on gender, age, and other demographics exist, women especially are present in much higher numbers than the prevailing literature would suggest. Women account for an estimated 10-20 percent of the Chinese population in Zambia, though observation suggests this figure could be even higher. Importantly, many of these women are in Zambia of their own right rather than accompanying a permit holder. Geographic diversity is also quite broad, with increasing representation from central and northern China. Though a departure from the traditional demographics, this can be largely explained by the employment-driven nature of Chinese migration. Most large companies hire workers from their home regions; for example, the Chengdu-based Lusaka Pan Brick Company hires workers from the same province of Sichuan.

Though outsiders often refer to “the Chinese” as a homogenous group, the Chinese population in Zambia is relatively disjointed. Multiple long-term residents described how the community has splintered as numbers have grown. In the 1990s, the approximately 200 Chinese residents of Lusaka all knew each other and united around their shared identity. As the Chinese migrant population has grown and diversified, individuals now self-segregate into smaller, more specialized groups, illustrated by the expanding numbers of Chinese community organizations. Twenty years ago only the Chinese Embassy existed; two new regional migrant associations were created in 2014 alone.

This diversity is also politically significant, as Chatelard asserts: “Individuals and families have their own agenda which is often quite separate from the concerns of the Chinese government…it is not a homogeneous community of agents collectively working to forward a coherent government agenda.” Chinese government representatives freely admit to maintaining contact almost exclusively with the large state-owned enterprises seeking Zambian government contracts, and rarely, if ever, interacting with the sizeable group of individuals pursuing private interests. In fact, they reported they are unable to even estimate the size of the Chinese community. The growing Chinese presence in Africa continues to set off global alarm bells, often viewed as a coherent neocolonialist strategy fully planned and implemented by the Chinese state. This new Chinese migration, however, is typified by a multitude of both public and private actors with independent motives, similar to other global population flows.

Migrant Assimilation

In some countries, “migrants...are virtually indistinguishable from the receiving population,” according to Castles. This is true in Zambia, where South African, Zimbabwean, and British immigrants share many cultural, occupational, and physical similarities with native Zambians. Due to the strong colonial and regional ties among these countries, it can be impossible to discern an individual’s nationality. India and Zambia also have a long migration and shared cultural history as former British colonies; many Indian migrants have so assimilated into Zambian society that they identify as Zambian.

Chinese migrants are more conspicuous and less assimilated into Zambian society than other migrant groups, at least partially due to the sheer newness of their presence. They also attract disproportionate attention due to their work on high-profile projects in visible industries such as construction, and a distinct appearance relative to most Zambian residents. Though no Zambian integration initiatives exist for any migrant population, the Chinese have remained by far the most segregated. Many attribute this to persistent language and cultural differences. Though an increasing number of Chinese migrants speak English, few Zambians are proficient in Chinese. However, the Chinese-sponsored introduction of Mandarin instruction in Zambian government secondary schools in 2014 has the potential to close this language gap.

Some Zambians praise the Chinese for living and working side-by-side with locals, rarely seen amongst other groups of expatriates. Others, however, are angered by what they view as Chinese migrants’ perceived sense of superiority, exploitation of local workers, and unwillingness to learn local languages. Cultural differences drive misunderstandings on both sides: the Chinese consistently complain about Zambians’ work performance, calling them lazy, while Zambians are mystified by the Chinese tendency to migrate without their families, feeling this signals a cold and unapproachable temperament.

The Chinese straddle a visible divide in the foreign populations in Zambia. More permanent migrants, mainly from other African countries such as South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Somalia, but also Indians and Lebanese, tend to interact on a peer-to-peer level with local Zambians. They are more established and integrated in-country. Expatriates are the second major group, mainly Americans and Europeans on contract with international organizations, governments, or religious organizations. It is highly unusual for anyone from this demographic to remain in Zambia longer than two years. The fact that Chinese both bridge and challenge these paradigms further makes them an enigma to observers.

Mirror of Larger Emigration Patterns

Since Zambia admits the majority of permit applicants, selection policies do not play a major role in determining immigrant demographics. Therefore, Zambian immigration data can provide insight into emigration patterns from major sending countries. Chinese immigration was negligible until “the influx” began around 2008, according to the Deputy Director of Operations at the Zambian Department of Immigration. This trend tracks with the overall growth in the stock of Chinese emigrants worldwide, which increased by 128.6 percent between 1990 and 2013—from around 4.1 million in 1990 to 9.3 million in 2013. China’s bid to join the World Trade Organization (WTO) necessitated reform of the country’s entry-and-exit procedures; simplification of the passport application process enabled many more Chinese nationals to travel and move abroad. Beijing’s increased attention to the continent—demonstrated by the establishment of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation in 2000—including investment and trade promotion likely spurred increased migration to Africa in particular.

Migration to Zambia as an example of South-South migration does not fit the prevailing global model of low-skilled migration to high-income countries. Zambian labor immigration is largely characterized by educated foreigners offering sectoral expertise and management experience. Dual labor market theory, which argues that cheap immigrant labor at the “secondary” end of the labor market will always be in demand since “primary” workers do not take such undesirable jobs, thus applies to the Zambian case—in reverse. Labor migrants enter the country not to occupy low-skilled jobs undesirable to “first-tier” natives, but instead to manage and share expertise with a relatively uneducated Zambian populace.

The global reach of multinational firms, worldwide demand for certain specialties, and formal treaty arrangements contribute to the function of migration systems as international labor markets. These elements are key to Chinese migration to Zambia, which has arisen from a growing history of political and economic cooperation between the two countries. Migration systems theory also applies to the Zambian immigration system more broadly, explaining many migrant flows through prior links including colonization, trade, and investment. The theory’s main weakness—its sheer breadth—can also be its strength, rendering it applicable to a larger spectrum of migration patterns.

Chain Migration from China?

Chinese migration to Zambia (and Africa more broadly) will likely continue to increase over the short- to medium term. China’s population pressures and recent international business expansions drive this trend. Chinese emigration historically follows a chain migration pattern, with pioneer migrants creating opportunities in the destination country for friends and family to follow behind. The Chinese population in Zambia is still quite new; as life in Zambia is publicized and further business opportunities are created, more migrants will surely follow.

Despite the highly publicized anti-Chinese rhetoric in Zambia, local officials are very aware of the important role the Chinese play in-country. Chinese influence is evident in the number of individuals present when stepping into any major government office, and extends beyond the official sphere into public life via daily vegetable markets and the recent proliferation of Chinese restaurants. The Zambian government’s recent commitment to fund public school Chinese-language instruction is only one example of its long-run dedication to the bilateral relationship. Despite the temporary nature of many Chinese migrants, the community as a whole will only continue to grow.

Editor's note: This article was amended on February 23, 2015 to clarify that not all companies hiring Chinese workers were listed individually in Table 1, but are included in the totals for each category. The values cited in the text have been amended to reflect this.

Sources

Castles, Stephen and Miller, Mark J. 2009. The Age of Migration. 4th ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Chatelard, Solange Guo. 2011. Unpacking the new “scramble for Africa”: a critical and local perspective of Chinese activities in Zambia. In States, regions and the global system: Europe and Northern Asia-Pacific in globalized governance, eds. Andreas Vasilache, Reimund Seidelmann, and Jose Luis de Sales Marques. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

de Haas, Hein. 2011. The determinants of international migration: Conceptualizing policy, origin and destination effects. IMI Working Paper 32, DEMIG Project Paper 2, University of Oxford, International Migration Institute, April 2011. Available Online.

Liu, Guofu. 2009. Changing Chinese Migration Law: From Restriction to Relaxation. Journal of International Migration and Integration 10 no. 3 (2009): 311-33.

Massey, Douglas S., Joaquin Arango, Graeme Hugo, Ali Kouaouci, Adela Pellegrino, and J. Edward Taylor. 1998. Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mung, Emmanuel. 2008. Chinese Migration and China's Foreign Policy in Africa. Journal of Chinese Overseas 4 no. 1: 91-109.

Park, Yoon Jung. 2009. Chinese Migration to Africa. SAIIA Occasional Paper 24, South African Institute of International Affairs, Johannesburg, 2009. Available Online.

Piore, Michael J. 1979. Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor and Industrial Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ratha, Dilip and William Shaw. 2007. South-South Migration and Remittances. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available Online.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Office. 2013. International Migration 2013: Migrants by Origin and Destination. New York: United Nations. Available Online.

Wang, Huiyao. 2014. Recent Trends in Migration between China and Other Developing Countries. Presentation at the International Organization for Migration, South-South Migration: Partnering Strategically for Development conference, Geneva, March 24-25, 2014. Available Online.

Zambian Department of Immigration. 2014. Immigration Permit Details. Lusaka: Department of Immigration.