France's New Law: Control Immigration Flows, Court the Highly Skilled

France's new immigration and integration law, adopted on July 25, 2006, aims to overhaul France's immigration system by giving the government new powers to encourage high-skilled migration, fight illegal migration more effectively, and restrict family immigration.

Although the new law does not take effect until early 2007, one of its pillars is already making itself felt. The number of people deported for not having the required documents reached nearly 13,000 by the end of July 2006, more than halfway to the Interior Ministry's 2006 goal of 25,000, inciting protests from tens of thousands of French citizens.

The unrest illustrates that France will not have an easy transition to a selective immigration system that 1) emphasizes employment-driven immigration at the expense of the 113,000 immigrants who arrive in France annually for family-related reasons and 2) that carries out a robust campaign against illegal migration.

Political Context and Debate

After years of debate, Nicolas Sarkozy, France's interior minister and leading presidential contender for the 2007 election, succeeded in passing a law that he argues will finally allow the government to control immigration. Addressing fellow government officials in July, Sarkozy argued that "selective immigration … is the expression of France's sovereignty. It is the right of our country, like all the great democracies of the world, to choose which foreigners it allows to reside on our territory."

However, immigrant rights organizations, African leaders, and many French citizens have criticized the law's limits on family reunification and its greater stringency in giving legal status to illegally resident immigrants. Politicians in France were not always in agreement either: The bill underwent over 300 amendments in the National Assembly and Senate before finally being passed.

Nevertheless, most policymakers agreed that France's immigration system is failing. Sarkozy argues that the failure can be traced to 1974, when migration inflows shifted from being worker-dominated to family dominated. The oil price shocks and resultant high unemployment in the early 1970s caused France to stop recruiting immigrant workers, yet migrants continued to enter France in large numbers to rejoin family members.

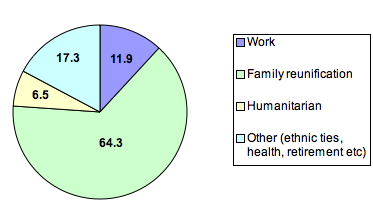

Today, family reunification accounts for nearly 65 percent of immigration to France — a major reason that the government wants to gain control over the numbers and types of migrants coming to the country (see Figure 1). Furthermore, the number of unauthorized migrants—an estimated 200,000 to 400,000 — fuels concerns over the rise in poverty, unemployment (8.9 percent), and social tensions.

As last fall's riots in the Paris suburbs illustrated, France has fallen short in its efforts to integrate its immigrants and their children, many of whom are French by birthright. More controlled migration, Sarkozy argues, will lead to better integration of migrants.

|

|

||

|

Finally, France is well-aware that it must compete with other global players for international talent. Countries such as Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia all actively recruit migrants and select them according to criteria that range from education and language skills to adaptability and age.

The July 24, 2006, Law

The new immigration and integration law has four main objectives:

- recruiting skilled workers;

- facilitating foreign students' stay;

- tightening the rules on family reunification; and

- limiting access to residence and citizenship.

Recruiting skilled workers

The new law authorizes the government to identify particular professions and geographic zones of France that are "characterized by recruitment difficulties." For those identified employers, the government plans to facilitate the recruitment of immigrant workers with needed skills or qualifications. However, this means employers who are not on the government-selected list may have more difficulty (or may face longer waiting periods) obtaining residence permits for migrant workers they wish to employ.

Under the new law, foreigners who possess skill sets of interest to French employers in the designated areas will be granted "skills and talents" visas, valid for three years. In a uniquely French twist, eligible candidates must be able to demonstrate that they will contribute to the economic or intellectual and cultural development of both France and their country of origin.

The new law's emphasis on "skills and talents" has already created tensions with those who are concerned that it will negatively impact developing countries, whose highest-skilled nationals will likely seek to emigrate.

In an attempt to ease fears about "brain drain," the government will only issue this visa to qualified immigrants from a developing country if the sending country has signed a "co-development" agreement with France or if the immigrants in question agree to return to their country of origin within six years. By doing so, the government aims to reframe the issue about the loss of some of sending countries' most skilled nationals by emphasizing the "circulation of skills."

Facilitating foreign students' stay

In addition to high-skilled workers, foreign students seeking to stay on in France after they complete their studies will also benefit from the new law by being given greater opportunities to do so.

With the new law, the government hopes to continue to attract foreign students coming to France to pursue higher education. Already, their numbers are growing. Between 2001 and 2003, the number of foreign students increased by 50 percent — a significantly larger increase than that which occurred in Italy, Germany, the United Kingdom, or the United States (see Figure 2).

During the 2004-2005 academic year, France admitted approximately 250,000 foreign students (in "degree/diploma track courses"), according to the Embassy of France in the United States. The French government reports that about half of France's foreign students come from francophone Africa.

|

|

||

|

The new law would require foreign students to receive approval to study in France from their country of origin. Once in France, foreign students who receive a masters or higher degree would be allowed to pursue a "first professional experience" that contributes to the economic development of both France and the student's country of origin. The student will be granted a six-month renewable visa to look for and take up work in France.

Tightening the rules on family reunification

The government's objective in modifying family reunification policy is three-fold: to ensure that immigrants respect French values, to promote their integration into French society, and to fight forced or polygamous marriages.

According to the president, the new law better defines conditions for family reunification. Accordingly, a family member of an immigrant who does not respect the basic principles of family life in France (recognition of the secular state, equality between a man and a woman, and monogamy) will not be allowed to enter France. Furthermore, an immigrant must now wait 18 months, instead of 12, to apply to bring a family member to France.

In an effort to prevent immigrant families from becoming dependent on France's welfare system, the law also requires immigrants to prove they can independently support all family members who seek to come to France. Specifically, they must earn at least the French minimum wage and not be reliant on assistance from the French state. Access to government assistance is also limited to European Union citizens. Those who reside in France longer than three months without working or studying must be able to support themselves without relying on social or medical benefits from the French government.

Another modification to the family reunification policy is that spouses of French citizens must wait three years (instead of two) before applying for a 10-year residence permit. Four years of marriage are required for the spouse of a French citizen to apply for French citizenship. Finally, an immigrant found to be practicing polygamy can have his or her visa revoked.

Limiting access to residence and citizenship

Sarkozy argued that the previous (1998) law "rewarded" immigrants who broke the law by offering them legal status after being residents for 10 years. The new law changes this by simplifying the procedure whereby the government can directly deport unauthorized migrants who are refused the right to stay in France.

Key exceptions were made for some illegal immigrants this summer when public outrage erupted over the deportation of immigrant families with school-aged children. In order to avoid deportation, these immigrants had to meet several criteria, including having a child enrolled in the French school system and demonstrating a "real will" to integrate.

Still, out of the 30,000 people who applied for regularization, less than 7,000 were granted legal status by mid-September 2006. Illegally resident immigrants who disturb the "public order" would also be vulnerable to deportation — a measure Sarkozy deems necessary to fight "delinquency" among foreigners.

Access to both citizenship and legal residence is dependent on the newly defined requirements of integration. For the first time in French history, a law explicitly states the integration responsibilities of immigrants.

Specifically, immigrants must sign a "welcome and integration" contract and take French language and civic courses. Before applying for permanent residence, immigrants must accordingly prove that they are "well-integrated" into French society. The government understands integration in this regard to mean that the immigrant respects and complies with the principles of the French Republic and has a sufficient knowledge of the French language.

Toward a Selective Migration System

As the French government prepared to pass the immigration and integration law in June, the Minister of Town and Country Planning, Christian Estrosi, appealed to fellow policymakers: "After 30 years of renunciation and blindness in front of the crucial challenge of immigration, after 30 years of uncertainty and non-choice, the moment has come to act!"

Sources:

Bennhold, Katrin Bennhold (2006). "Sarkozy shores up support." International Herald Tribune, September 3.

EU Observer (2006). "Migrants keep coming as EU seeks new border plans." September 4.

Embassy of France. "Studying in France (a few facts on...)" Available online

Expatica (2006). "France to amnesty 7,000 immigrant families." September 18.

Jamet, S (2006). "Improving Labor Market Performance in France." OECD Working Papers, No. 504.

Journal Officiel de la Republique francaise: Article 6, Chapter 1 of Lois nº 2006-911 du 24 juillet 2006.

Communique du Conseil des ministres du President de la Republique, March 29, 2006.

Journal Officiel de la Republique francaise: Article 18, Chapter 3 of Lois nº 2006-911 du 24 juillet 2006.

Journal Officiel de la Republique francaise: Chapter 5 of Lois nº 2006-911 du 24 juillet 2006.

La vie publique: loi du 24 juillet 2006 relative à l'immigration et à l'intégration (La documentation française).

Migration News (2006). "France, Germany, Benelux." Vol. 13, No. 3. UC Davis, July. Available online

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, France. "Welcoming foreign students to France — some figures."

Ministry of the Interior, Intervention de M. Nicolas Sarkozy, press conference, July 24, 2006.

Ministry of the Interior: Vote du projet de loi relative à l'immigration et à l'intégration, June 30, 2006.

INSEE, August 2006.

Ministry of the Interior, Intervention de M. Nicolas Sarkozy, July 24, 2006.

OECD International Migration Outlook 2006 (data approximated from 2004). UMP: Les grands discours, Nicolas Sarkozy à l'Assemblée nationale, June 9, 2005.