From Horseback to High-Tech: U.S. Border Enforcement

A Customs and Border Protection officer uses advanced fingerprinting equipment to identify an individual being processed at the border.

Borders are a concrete representation of a nation's statehood, as each state seeks to control entries into its sovereign territory. Indeed, the ultimate responsibility of a government is to safeguard the security and well-being of its citizens.

In the minds of the American public, the term "border enforcement" conjures images of Border Patrol agents trying to prevent the entry of drugs, thugs, and illegal immigrants along a relatively uncontrolled, and, at times, chaotic U.S.-Mexico border. And for most of the 20th century, that was an accurate characterization, as enforcement resources were allocated in that manner.

Genuine border enforcement, however, consists of integrating the work, resource allocation, and information capacity of all ports of entry — including northern and southern land borders, airports, and seaports as well as the territory between official ports of entry and U.S. consulates abroad — in an effort to protect the country.

Though some components of this broader definition were in the minds of key policymakers by the mid 1990s, only in the last few years has this holistic approach to border enforcement become more widely accepted as a new paradigm for serious policy discussions.

Over the last 20 years, border enforcement has variously sought to prevent the smuggling of alcohol and drugs, the flow of illegal immigrants, criminal violence in the border region, and threats posed by terrorists.

At the same time, border control has also evolved from a low-tech, one-agency exercise focused strictly on the Southwestern border to a far more encompassing concept. It includes multiple agencies, the extensive use of technology, and a broad geographic focus that not only includes the entire U.S. border and coastline but also transit states and countries of origin.

|

Historical Background

Seventy-five immigration inspectors on horseback first began enforcing immigration laws on the U.S.-Mexico border in 1904. The U.S.-Mexico border was not even formalized until the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War.

Congress first established an independent Border Patrol as part of the restrictive Immigration Act of 1924; 450 employees were deployed along both U.S. land borders in response to illegal entries and alien smuggling. By 1930, the Border Patrol's size had nearly doubled, and additional growth ensued during World War II based on national security concerns.

The mission of the Border Patrol, working between official inspection stations, was to exclude "illegal aliens," including Asian and European immigrants trying to circumvent newly established entry quotas by illegally entering the United States through Mexico.

Yet as Prohibition went into effect, resources were diverted to stem the illicit flow of alcohol (particularly along the Canadian border). The 1933 repeal of Prohibition coincided with the Great Depression and reduced flows of undocumented labor into the United States, decreasing the demand for border enforcement during the 1930s.

With a few exceptions, border enforcement failed to rise again to national prominence in policy debates until the late 1970s. In part, this inattention reflected the fact that the majority of Mexico-U.S. migration from 1942 to 1964 was legal under the Bracero Program, which brought millions of Mexican workers to the United States to offset labor shortages, most of whom returned home seasonally.

Furthermore, Mexicans were able to enter the United States without quantitative limit prior to the 1965 amendments to the Immigration and Nationality Act (implemented in 1968). And it was not until 1976 that Congress extended the strict, 20,000 per-country limit and preference system to countries in the Western Hemisphere, including Mexico.

By the late 1970s, migration pressures mounted in Mexico due to the new numerical restrictions. Apprehensions and deportations increased dramatically from earlier in the decade to more than one million annually. President Carter introduced a plan in 1977 to address illegal immigration that included enhanced enforcement efforts at the U.S.-Mexico border.

By 1978, Congress had appropriated funds for 2,580 new Border Patrol staff, accounting for one-quarter of total Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) staff at that time. Although a stalemated Congress failed to act on President Carter's plan, it did create the Select Commission on Immigration and Refugee Policy (SCIRP) in 1979 to study and make recommendations on illegal immigration and immigration reform. The recommendations of the Select Commission became the basis of the policy debate and legislation throughout the 1980s.

IRCA and Its Effects: 1986 to 1992

After many years of debate, Congress passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA). The basic concepts of IRCA, as exemplified by the first three titles of the bill, were "Control Illegal Immigration," "Legalization," and "Reform of Legal Immigration." Based on the Select Commission's conclusions, the message was to "close the back door and open the front door."

IRCA's attempt to control and reduce illegal immigration focused primarily on imposing sanctions on employers who hired unauthorized workers and legalizing the existing undocumented, rather than on enforcement at the border.

Yet the law also provided a significant infusion of resources to enhance the Border Patrol's existing approach to the detention and apprehension of illegal entrants, calling for a 50 percent increase in Border Patrol personnel in fiscal years (FY) 1987 and 1988. The Border Patrol also was tasked with assisting in employer sanctions, employer education, and the apprehension and removal of criminal aliens.

At the time of IRCA's passage, Congressional appropriations already had increased to fund nearly 3,700 Border Patrol staff, growing to over 30 percent of total INS staff. In compliance with the bill's growth requirements, though, that increased to more than 5,500 staff in 1987 with appropriations nearly double what they had been only five years earlier.

Moreover, the Border Patrol received an influx of new equipment, including 22 helicopters for all nine sectors (up from a total of two helicopters in one sector) and hundreds of night-vision scopes, night vision goggles, and surveillance systems. Additional Border Patrol stations, checkpoints, and new detention centers were also built.

In fact, given IRCA's emphasis on employer sanctions and legalization, border enforcement received a disproportionate percentage of the resulting financial resources: 57 percent ($70.5 million) of the supplemental funds for IRCA's implementation in fiscal year (FY) 1987 targeted border enforcement, compared to 27 percent for sanctions enforcement and 14 percent for alien removal.

Overall, the INS enforcement budget grew substantially following IRCA, with enforcement staffing increasing between 1986 and 1990 by 40 percent to 11,000 employees and the budget by 90 percent to $700 million. The Border Patrol accounted for approximately 40 percent of the INS's total enforcement budget and staff at that time.

A number of additional policy changes in 1986 highlighted a growing connection between border enforcement, the military, and counter-narcotics programs. Namely, in 1986, the Border Patrol was given the lead role in drug interdiction between ports of entry; its legal authority was formally expanded in 1987. In addition, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, enacted only 10 days before IRCA, enhanced INS's ability to deport aliens with drug convictions and provided additional funding to fulfill its role in drug interdictions. This increasing role of the Border Patrol in drug control resulted in qualitative changes in their equipment and approach, including use of military approaches and technology.

By 1989, the "War on Drugs" was an increasingly central feature of U.S. foreign policy. The second Anti-Drug Abuse Act was passed in 1988, requiring the INS to deport certain aggravated felons following the completion of their sentences. The focus on drug enforcement proved beneficial for the INS enforcement budget, as it received additional funding of equipment and personnel. In fact, this supplemental drug funding was the only discretionary funding INS received once IRCA-related budget increases declined.

By this time, anxieties regarding illegal immigration had receded slightly; illegal entries also had declined temporarily as a result of IRCA's deterrent effect, with Border Patrol apprehensions in 1989 only 53 percent of the 1986 levels (see Table 1). At the same time, the Border Patrol's responsibilities for employer-sanctions enforcement and removal of criminal aliens contributed to a decline in the amount of time spent patrolling the southern border.

|

Many of the Select Commission's other recommendations were addressed in the Immigration Act of 1990 (known as IMMACT). IMMACT focused on expanding legal immigration (ironically at a time in which the U.S. economy was in a downturn), but it also called for an additional 1,000 Border Patrol agents and allowed funds from increased penalties to be used for repairing, maintaining, and constructing border barriers. IMMACT also created the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform, with the mandate to examine and evaluate the legislation's impact.

In 1991, the U.S. Navy built a 10-foot high wall of corrugated steel between San Diego and Tijuana using surplus military aircraft landing mats. The wall stretched for seven miles along the border in the Chula Vista sector (in 1993 it was expanded to 14 miles, extending into the Pacific Ocean) and marked a momentous upgrade from the chain-link fences that had previously demarcated the border.

The wall was supposed to reduce drug smuggling, but its location overlapped with the most heavily trafficked crossing point for illegal immigrants. It drew significant political attention in the United States and Mexico, particularly given the two country's increasing economic and political integration.

Although perhaps the most visible, construction of this barrier was only one component of broader border upgrades during this time period, including the provision of additional helicopters and new technologies such as infrared radar equipment and a mobile surveillance system.

By the end of 1992, the Border Patrol's funding had reached over $325 million, and its staffing levels (just under 5,000) continued to represent over 40 percent of all INS staff. The simultaneous growth in cross-border business and in border enforcement led to what political scientist Peter Andreas called the paradox of "a barricaded border and a borderless economy."

A New Border-Control Strategy: 1993 to 2001

Concern about immigrants in general, and illegal immigrants in particular, reemerged as a national priority in the 1990s, beginning with the January 1993 shooting at CIA headquarters by a Pakistani who had entered the U.S. illegally and applied for political asylum. One month later came the bombing of an underground garage at the World Trade Center building in New York City, spearheaded by a Kuwaiti who had entered with a false Iraqi passport. In June 1993, Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman (the "Blind Sheikh"), who had been issued a visa to enter the United States despite his name being on a watch list of suspected terrorists, was arrested for his role in plots to blow up landmarks in New York and California.

In addition to the emerging connection between migration and terrorism, more emphasis was placed on border controls. In California, voters were considering California's Proposition 187 to deny social services, health care, and public education to illegal immigrants. Governor Wilson embraced the proposition as part of his successful reelection campaign, and the measure passed easily in 1994.

On September 19, 1993, newly arrived Border Patrol Sector Chief Silvestre Reyes initiated Operation Blockade along the El Paso/Ciudad Juarez border. The El Paso operation deviated from the traditional enforcement strategy of apprehension and removal by deploying more than 400 of the sector's 650 agents to 24/7 duty along the border line.

Later renamed Operation Hold the Line, this turned out to be the first step in what would become a major shift in Border Patrol and INS policy nationwide to prevent the illegal entries or intercept attempted entrants, rather than apprehending them after entry. The operation had an immediate and visible impact on the El Paso community. Illegal entries and apprehensions declined dramatically, as did petty crime and charges of human rights violations by Border Patrol agents.

Attorney General Janet Reno visited the Southwest border in August 1993 following a July presidential announcement regarding funding for agents and technology. In February 1994, she and INS Commissioner Doris Meissner announced a multiyear strategy to curb illegal immigration. The strategy's centerpiece was strengthening border control by focusing resources on the traditionally busiest crossing corridors for illegal immigration into the United States. It called for adding 1,000 Border Patrol agents in the areas of greatest need and expanding the use of infrared scopes, lighting, secondary fences, and upgraded sensors.

The policy shift was cemented and reflected in the Border Patrol's 1994 strategic plan, which can be summarized by two concepts — "prevention through deterrence" and "targeted enforcement." These concepts are crucial to understanding border control during the 1990s and represent a significant break from previous policies.

Recognizing that sealing the border was unrealistic, the Border Patrol instead aimed to concentrate resources in major entry corridors (rather than sprinkling them evenly across the border), establish control, and then sustain the resource commitment to maintain control as enforcement efforts moved elsewhere across the border. They hoped this approach would raise the risk of apprehension high enough to deter illegal entry or redirect traffic to areas that were harder to cross and more advantageous to enforcement efforts; disrupt existing entry and smuggling routes; and help restore confidence in the border's integrity.

The four-phase plan began in California and West Texas and, throughout the 1990s, was replicated in other sectors along the border. Operations included the addition of hundreds of agents and motion-detection sensors in the selected sectors; construction of high-intensity, stadium-type lighting, new roads, and miles of steel fencing; and installation of an automated fingerprint system to identify criminal aliens and repeat crossers (IDENT).

Many of these technologies originated from the military, and the military continued to assist with construction, maintenance, and operation of equipment. For instance, IDENT technology, unveiled in 1994, was based on the Navy's Deployable Mass Population Identification and Tracking System, and it serves as the underlying architecture of the post-9/11 tracking system known as US-VISIT (United States Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology).

In September 1994, the U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform issued its first interim report to Congress, asserting that the United States needed to restore credibility to its immigration policy. To do so, the commission called for improved border management to meet the twin goals of preventing illegal entries while facilitating legal ones.

In particular, the commission endorsed the strategy used in Operation Hold the Line and recommended increased resources for prevention (including staff, technology, data systems, and equipment), increased training for border officers, formation of a rapid response team, use of fences for the purposes of reducing border violence, and systematic evaluation of the effectiveness of new strategies through techniques other than apprehension rates. The commission also concluded that "border management alone will not deter unlawful immigration."

Furthermore, the commission supported efforts to address human rights complaints, to coordinate efforts with the Mexican government, and to improve operations at legal ports of entry, including the automation of arrival and departure records to enhance exit controls and better determine overstay rates.

As had been the case with the Select Commission, some of its recommendations became the basis of future legislative and policy changes.

By 1996, INS understood that if it was successful with patrolling the border, not only would illegal entry attempts shift to sectors that had not yet been addressed, but traffic might shift to other modes of entry, including the use of fraudulent documents at legal ports of entry. Thus, Congress authorized a doubling of inspectors at ports of entry between 1994 and 1997 precisely to combat the use of fraudulent documents. The additional 800 INS inspectors in the Southwest led to a total of 1,300 by March 1997.

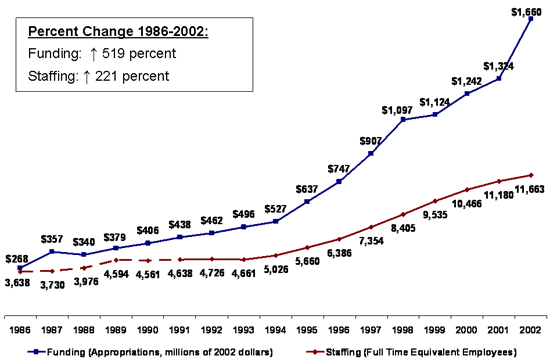

Similar support, however, was not initially extended to the State Department's role, which is the first line of defense in border enforcement since it issues visas. As a result, there was insufficient staffing at overseas consulates, ineffective interagency data exchange, and a lack of necessary technological improvements. This contrast between a dramatically growing INS and a stagnant State Department budget in the 1990s (as shown in Figure 1) was particularly sharp given that both were funded through the same appropriations bill, and, in many ways, competed for the same limited funding.

|

Yet in a sign that consular work abroad was becoming a more important component of border enforcement, the INS and State Department launched DataShare in the mid 1990s. Once fully deployed, the program electronically transferred an immigrant-visa applicant's full file with photo and fingerprints from consulates to ports of entry, allowing inspectors to compare the applicant with his or her application. After 9/11, the program was expanded to include nonimmigrants.

INS also expanded its enforcement efforts abroad, opening 13 new offices in Europe, Africa, Asia, and Latin America in "Operation Global Reach." The idea was to work with law enforcement officials and transportation authorities in various countries to address the growing problems of smuggling and trafficking within source and transit countries.

In 1996, Congress passed three major pieces of legislation that had immigration implications. Most important for border enforcement was the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), which effectively ratified aggressive border enforcement. In so doing, IIRIRA also planted the seeds of many future security efforts.

Perhaps most high-profile were IIRIRA's requirements for tracking entries and exits of foreign students in particular and foreign-born visitors more generally. Both programs became the basis of post-9/11 initiatives. INS had proposed a new automated system for information on international students and exchange visitors in 1995 in response to FBI concerns about the activities of foreign students following the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.

A pilot program began in the late 1990s but was delayed for a variety of reasons, including disagreements between lawmakers and the higher education establishment over fee collection and technical problems in the system. As part of IIRIRA, Congress mandated that such a system be fully operational by 2003 and be funded by fees collected from students.

Similarly, Section 110 of IIRIRA required by September 1998 the development of an automated entry-exit tracking system that would identify visa overstays by recording departures of non-U.S. citizens and matching them with entry records. It provoked strong reactions from communities and businesses along the Canadian and Mexican borders and, though modified by a 2000 law, has since been implemented as the US-VISIT program at air, sea, and land points of entry nationwide.

Defining border enforcement more broadly than before, IIRIRA also improved document security, authorized additional inspectors at ports of entry, and promoted measures meant to facilitate legitimate traffic. Although IIRIRA required the Border Patrol to increase its strength by 1,000 agents per year, such rapid growth was unrealistic for a number of reasons. It was especially difficult to recruit, train, and retain a sufficient numbers of agents in the dynamic economy of the 1990s.

By September 1998, the Border Patrol had grown to 8,000 employees (93 percent of whom were deployed on the Southwest border), and the number of inspectors at land ports of entry had grown to 2,000 (75 percent of them on the Southwest border).

In the mid 1990s, the United States signed formal agreements with the governments of Canada and Mexico that addressed border enforcement and legitimate travel issues. These cooperative agreements and deep relationships allowed all three governments to take many of the actions they did in the aftermath of 9/11 and laid the foundation for additional cooperative agreements and shared visions for the future with regard to border enforcement.

Consistent with the fourth and final phase of the 1994 border control strategy, INS announced its Northern Border Strategy in the fall of 2000, a year after an Al Qaeda operative was apprehended while attempting to cross the border into Washington state. Its primary objective was to enhance the security of the shared border (i.e., protecting against terrorists as well as cross-border crime and illegal immigration) while "efficiently and effectively managing the flow of legitimate travelers and commerce." It also specified that it would not replicate the strategies from the southern border.

In many ways, the Northern Border Strategy's focus on intelligence, information, and coordinated intergovernmental efforts to push the border outward foreshadowed enforcement approaches that would gain in primacy following the attacks of 9/11.

By September 30, 2000, the Border Patrol had reached over 9,000 agents, with 93 percent of them deployed along the Southwest border, and a budget in excess of $1 billion per year. The number of hours those agents spent on border-enforcement activities also increased, as had the number of remote video surveillance systems. Moreover, the Southwest border included 76 miles of barrier fences, and the Border Patrol's five-year plan called for additional technology along both the northern and southern borders.

September 11, 2001, to the Present

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, raised political and public attention on border enforcement to unprecedented levels. Given the modes of entry of the 9/11 hijackers, the majority of policy changes that followed focused on temporary visitors to the United States who entered through legal means at official ports of entry such as airports, rather than by crossing the Southwest border. Post-9/11 reforms thus had a relatively modest impact on the day-to-day operations and responsibilities of the Border Patrol.

Yet the attacks solidified the notion that immigration functions must be treated as a key aspect of national security, and that border enforcement should not be limited to the U.S.-Mexico land border alone.

Building on programs initiated in the 1990s, security gaps were addressed through new laws, such as the 2001 USA Patriot Act and the 2002 Enhanced Border Security and Visa Entry Reform Act, which have led to greater information sharing; modifications to visa policies and procedures overseas, including expanded international cooperation; enhanced document security and documentary requirements; accelerated implementation of nonimmigrant tracking programs; and institutional changes. The 2002 National Homeland Security Strategy included border and transportation security as one of six critical mission areas in securing America from terrorist attacks.

Institutional changes have been among the most visible shifts since 9/11, including the creation of a major new actor on border enforcement issues. INS was abolished in March 2003, and all its immigration-related functions of were transferred into the newly created Department of Homeland Security (DHS), in a merger of some 180,000 employees from 22 different agencies.

Border Patrol agents and port of entry inspectors from Customs, INS, and the Agriculture Department's Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service fell within the purview of the new Bureau of Customs and Border Protection (CBP). The other two components of DHS with legacy INS responsibilities are Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

CBP's priority mission is "preventing terrorists and terrorist weapons, including weapons of mass destruction, from entering the United States," but CBP is also responsible for the missions of its legacy agencies, including "stemming the tide of illegal drugs and illegal aliens, securing and facilitating legitimate global trade and travel, and protecting our food supply and agriculture industry from pests and disease."

The primary mission of the Border Patrol remained unchanged until a new strategy statement issued in March 2005 formally prioritized preventing terrorists and terrorist weapons from entering the United States. The statement also reaffirms the agency's traditional mission of preventing the entry of "illegal aliens, smugglers, narcotics, and other contraband."

The new strategy specifies a goal of establishing and maintaining "operational control" of the border, particularly the northern and southern borders, recognizing that failure to do so poses a security threat. The Border Patrol defines "operational control" as "the ability to detect, respond, and interdict border penetrations in areas deemed as high priority for threat potential or other national security objectives."

Although the strategy does not specify a timeline and acknowledges that it is difficult to measure success, the Border Patrol aims to achieve its objectives through a combination of personnel, technology, equipment and infrastructure, enhanced mobility, deployment, intelligence efforts, partnership with other federal and local law enforcement agencies, and an improved command structure.

Yet, even as the 9/11 attacks provided the high-level political support necessary to advance a broader understanding of border enforcement, policymakers have pushed to do "more of the same." Even greater financial, personnel, and technological resources have been directed toward the border, including the northern border.

In 2004, the Intelligence Reform Act specified an annual increase of at least 2,000 full-time Border Patrol agents from FY 2006 through FY 2010, an increase of at least 800 full-time immigration and customs enforcement investigators annually during the same time period, and an increase in detention space and expedited removal (the Patriot Act had already expanded detention and deportation authority, created new grounds of inadmissibility, and limited judicial review).

By the end of 2002, Border Patrol staffing had climbed to over 11,000, and there were over 6,000 immigration inspectors (the ranks of inspectors at ports of entry were soon supplemented by the 10,000 former customs and 1,500 former agriculture inspectors who were also merged into DHS) (see Table 2).

|

The government has been reluctant to halt the traditional response of personnel and barrier enhancements along the border line despite a competing desire to undertake a broader approach to border enforcement. For instance, DHS Secretary Chertoff has articulated that a border-wide approach — such as the department's "Secure Border Initiative" (SBI), a comprehensive, multiyear plan to secure America's borders and reduce illegal migration — is necessary to address enforcement challenges.

Yet the Arizona Border Control Initiative, begun in March 2004, has deployed hundreds of additional Border Patrol agents and doubled air support. Of the 1.1 million apprehensions in 2004, 52 percent occurred in Arizona, evidence that illegal flows have shifted away from well-protected urban areas in California and Texas to terrain that is less populated and more dangerous to cross.

More generally, the Border Patrol launched another hiring campaign in 2005 because the Border Patrol chief stated the agency was overwhelmed and needed to gain control of the border to stop illegal immigration. After August 2005 declarations of states of emergency by the governors of Arizona and New Mexico, Secretary Chertoff acknowledged a need to strengthen border control efforts. But he also asserted, "A strategy that simply hires a lot of border patrol agents and puts them on the line is not an effective strategy."

Conclusion

This historical review indicates that border enforcement generally has reflected the political priorities, legislative changes, and context of the broader economic and political environment. The Border Patrol — and border enforcement — have adapted to the threat of the period, be it countering the smuggling of alcohol or drugs, the flow of illegal immigrants, criminal violence, or the threat posed by terrorists. Indeed, Border Patrol agents supported law enforcement efforts in New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Perhaps for these reasons, the Border Patrol has fared better than many other agencies from a resource perspective (see Figure 2). With the border consistently portrayed as a security vulnerability, turning to law enforcement agencies and military measures has been quite predictable.

|

This tendency to target ever more resources (staffing, funding, and technology) toward the traditional approach to border enforcement at times conflicts with a counter-trend — the ongoing efforts, usually originating within executive branch enforcement agencies, to adopt more expansive approaches to border enforcement. These approaches incorporate legal points of entry, overseas consulates, international cooperation, and border enforcement more completely into a broader policy framework.

Yet, to the extent that these broader notions of border enforcement imply a shift of resources away from the border area, they confront significant political barriers. Border enforcement may be the only component of immigration policy that consistently garners a broad political consensus, which explains the tendency to continue directing additional resources toward these traditional approaches regardless of agency capabilities and policy outcomes.

As a result, economic disparities and other fundamental factors underlying illegal migration, drug smuggling, and the threat of terrorism have often been overlooked in favor of an overwhelming focus on border-area interdiction of illegal immigrants and drugs, which, in the final analysis, are the symptoms, not the causes, of deeper problems.

Intrinsically, the nature of borders means people will try to violate them. Terrorists and others will always probe vulnerabilities to take advantage of or circumvent any weak points. Thus, regardless of other events and policy decisions, border-enforcement issues need to be grappled with, as they are likely to remain a front-burner issue for the foreseeable future.

This article is based on Deborah Waller Meyer's Insight published in November 2005 as part of the research prepared for the Independent Task Force on Immigration and America's Future. The PDF version is available here.

Sources:

Andreas, Peter (1998-1999). "The Escalation of U.S. Immigration Control in the Post-NAFTA Era." Political Science Quarterly 113, no. 4.

Andreas, Peter (2000). Border Games: Policing the U.S.-Mexico Divide. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Bean, Frank et. al (1994). Illegal Mexican Migration and the United States/Mexico Border: The Effects of Operation Hold the Line on El Paso/Juarez. Austin: Population Research Center. Available online.

Dunn, Timothy J. (1996). The Militarization of the U.S.-Mexico Border, 1978-1992: Low-Intensity Conflict Doctrine Comes Homes. Austin: Center for Mexican American Studies, University of Texas at Austin.

General Accounting Office (2001). INS's Southwest Border Strategy: Resource and Impact Issues Remain After Seven Years. GAO-01-842, August. Available online.

Juffras, Jason (1991). Impact of the Immigration Reform and Control Act on the Immigration and Naturalization Service. Santa Monica: The Rand Corporation and the Urban Institute Press.

Massey, Douglas (2003). Beyond Smoke and Mirrors: Mexican Immigration in an Age of Economic Integration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks (2004). The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. Available online.

Storrs, K. Larry (1998). Mexico's Counter-Narcotics Efforts Under Zedillo, December 1994 to March 1998. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, March 4.

Tichenor, Daniel J (2002). Dividing Lines: The Politics of Immigration Control in America. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform (1997). "Border Enforcement," December 1993 Briefing Paper in the Appendix, Curbing Unlawful Migration. Washington, DC: U.S. Commission on Immigration Reform.