Immigrants, Welfare Reform and the Coming Reauthorization Vote

The U.S. Congress faces the decision of whether or not to modify provisions of a 1996 welfare reform law that barred many noncitizen immigrants from accessing federally funded benefits such as Medicaid and food stamps. These discussions are part of the reauthorization process of the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), which denied federal welfare benefits to most legal immigrants during their first five years of U.S. residence and placed other restrictions on legal immigrants' eligibility for benefits.

The debate is certain to be heated. On one side are some lawmakers, many allied with immigrant advocates, who maintain that cutting federal funding has harmed new and often vulnerable populations. These proponents argue that the government unfairly changed the eligibility rules for legal immigrants who had not been denied access in the past.

The other side gathers those who believe that some immigrants come to the United States with the intention of taking advantage of a system that provides for immigrant families, as well as those who would like to limit immigrant use of benefits because of the excessive burden such programs and services allegedly place on the federal budget.

State and local governments, meanwhile, may throw their weight behind lawmakers opposed to the immigrant restrictions in the 1996 Act. Their stake in the debate is enormous. Ever since the change in federal funding rules, state authorities have grappled with whether and how to use their own limited revenues to meet the needs of their immigrant communities in general, and immigrant children in particular. State efforts to balance fiscal health with social responsibility, along with partial rollbacks of the Act at the federal level, have since 1996 produced a complicated patchwork of eligibility rules for various immigrant groups and programs.

The reauthorization issue plunges Congress into complicated political terrain. Understanding the current debate, and the likely consequences of the Sept. 30 vote for immigrants and their communities, requires a closer look at the history of welfare reform and immigrant eligibility.

|

|

Origins and Effects of the 1996 Act

The immigrant eligibility restrictions in the 1996 law were included largely at the urging of the Republican leadership that controlled both Houses of Congress after the 1994 elections. They had two goals: balancing the budget and devolving power to the states. Their efforts were successful largely because public and (partisan) political concerns about immigrants had peaked. The search for large budget cuts quickly closed in on immigrant benefit use.

Prior to 1996, legal permanent residents (LPRs) were generally eligible for federal benefits on the same basis as U.S. citizens. States were not permitted to restrict access to federal programs on the basis of citizenship status. However, the Act instituted several restrictions that served to fragment the eligibility of the immigrant population for public benefits. All citizens, including immigrants who had naturalized, retained eligibility for federally funded programs. Most noncitizens, however, including previously eligible legal immigrants who had not yet naturalized, became ineligible under the new rules.

With the exception of refugees and asylees, LPRs with 40 quarters of work, and those in the military, all noncitizens were barred from participation in most of the major means-tested federal benefit programs for which eligibility was based on need: TANF, food stamps, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and Medicaid. For the TANF and Medicaid programs, states were given the option to use federal funds to serve immigrants who had arrived before the Act took effect.

However, immigrants who entered the U.S. after the 1996 Act was signed into law were made ineligible for any assistance using federal funding for their first five years of residence -- a situation that remains today except for a restoration of food stamps to the children of legal immigrants regardless of date of entry.

These complicated rules created various classes of eligibility for benefits.

|

Post-1996 Federal Restorations

While many of the exclusionary conditions of the Act for noncitizens still stand, there have been several important restorations by Congress. The impetus for restoring eligibility came, in these cases, from advocates and bipartisan support. Even as President Bill Clinton signed the bill into law in August of 1996, he vowed to restore access to benefits to immigrants.

The Balanced Budget Act of 1997 (BBA) restored SSI payments to most legal immigrants who were residing in the United States before August 1996. The BBA also clarified that as long as an individual was receiving SSI, he or she remained eligible for Medicaid.

In 1998, the Agricultural Research, Extension, and Education Act of 1998 restored eligibility for food stamps to immigrant children, elderly immigrants and disabled immigrants who resided in the U.S. prior to the date of the passage of the 1996 Act. The law also extended the refugee exemption from the food stamp bar from five to seven years.

The Farm Security and Rural Investment Act of 2002, signed into law in May, reinstated access to food stamps for legal immigrants who have been in the U.S. for five years, and to legal immigrants' children and legal immigrants receiving disability benefits, regardless of their date of entry into the United States.

State and Local Response

The effects of the 1996 Act were strongly felt by state and local authorities. States had to decide whether they should continue to use federal funding to provide TANF and Medicaid to eligible legal immigrants who had arrived before the Act took effect. They were also faced with the decision of whether or not to create state-funded programs for immigrants who were no longer eligible for federally funded benefits.

Moreover, the Act explicitly limited state and local governments' authority to provide any benefits to undocumented immigrants. Doing so meant they had to enact a state law after Aug. 22, 1996, that "affirmatively provides for such eligibility." In other words, state governments must declare that they are making a choice to provide undocumented immigrants with benefits.

In response to these provisions, all 50 states have extended access to TANF benefits to legal noncitizens who arrived before the 1996 Act took effect. Every state except for Wyoming has also extended pre-enactment noncitizen access to Medicaid. It is not surprising that states largely took this pragmatic move since they can use federal funding for pre-enactment immigrants.

However, all but five states, including Texas, have decided to use their federal funding for TANF and all but seven states have decided to use their federal funding for Medicaid for post-enactment immigrants who have resided in the United States for at least five years. In addition, 23 states, including California and New York, have created state-funded TANF programs for some or all of the legal immigrants who are ineligible for federal TANF because of the five-year bar. At the same time, several states have provided state-funded health care or food stamp benefits to at least some immigrants who are no longer eligible for federal benefits.

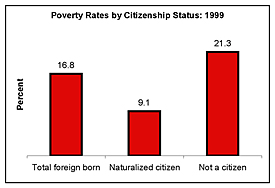

Another way local areas have adapted to the new reality of paying for the benefits of noncitizens has been to encourage the naturalization of eligible immigrants. Soon after the 1996 Act took hold, New York City and California's Santa Clara County both set up programs to encourage naturalization and assist immigrants with the process of becoming a U.S. citizen. Arguably, promoting citizenship meant that immigrants would move into a status that would make them eligible for federally funded programs, thus shifting the fiscal burden back to the federal sources of funding.

There was a surge in naturalization applications following the implementation of the welfare law; however, the rise in applications corresponded with several other programs that also affected the naturalization rate. For instance, the large cohort of legalization recipients who became eligible for naturalization under the 1992 Green Card Replacement Program and the 1995 Citizenship USA initiative also boosted naturalization applications.

The 2002 Debate

The current congressional debate is taking place against a backdrop of partial restorations of the eliminated benefits as well as a very busy period of congressional decision making.

In a sign that lawmakers could be moving toward further restorations, the Senate Finance Committee recently approved a bill to reauthorize 1996 legislation that restores some of the benefits stripped by the Act. The restorations for legal immigrants are for TANF-funded assistance and services as well as healthcare. While the Finance Committee proposal did not originally propose restoration of health benefits, the committee did approve an amendment by Senator Bob Graham (D-FL) to allow states the option of providing healthcare to legal immigrant children and pregnant women. The amendment will be included in the bill that will go to the Senate floor.

On the other hand, the recent House welfare reauthorization bill failed to include any restoration of eligibility for legal immigrants. In addition, the Bush administration did not include in its welfare reauthorization proposal TANF-funded benefits and services or healthcare coverage for recent immigrant families.

Votes and Outcomes

The difference between the House-passed bill and the bill that will go to the Senate floor sets up an inevitable clash on this issue in the conference committee. This year's heavy press of congressional business may mean that the reauthorization debate is extended past Sept. 30.

State and local governments are particularly concerned with the outcome of this process, for two important reasons.

First, currently, in order to provide assistance to post-enactment immigrant families, state and local governments must use funding from their already strapped budgets. A vote this fall to allow the use of federal funds for benefits and services would make it easier for states to cover these expenses. States use some TANF funds for cash assistance, but most funds are used for services such as childcare and transportation that help people get and keep jobs.

Second, immigrant rights advocates and their allies are concerned for the well-being of children in immigrant families. National-level data show declines in program participation among citizens and noncitizens alike. However, the declines have been steeper for noncitizens. It is relevant to note that many immigrant-headed families have members with differing legal statuses; about three-quarters of all children living in immigrant-headed households are U.S. citizens. There has been a demonstrated decline in benefit use by such families in the latter half of the 1990s, even though the children in these families are citizens, and thus qualify to receive benefits. Numerous studies have shown that confusion about eligibility among both caseworkers and immigrants has produced a "chilling effect." Other research shows that parents do not enroll eligible children when the adults in the family are ineligible. At this writing, there is bipartisan support for providing healthcare coverage for children in these families.

Given the crush of business in the Senate this year, it is possible the reauthorization vote may be delayed. However, assuming the Senate passes a bill this year, it is very likely to include restorations from the Senate finance bill, namely TANF and healthcare benefits for immigrants. After the Senate passes its bill, an appointed conference committee from both Houses of Congress is charged with negotiating a resolution of the differences between House and Senate versions of TANF reauthorization bills.

The recommendations of the conference committee are likely to constitute the bill that is passed by both chambers and signed into law by the president. However, it is impossible to predict the outcome of this process at this time.