You are here

A Warm Welcome for Some: Israel Embraces Immigration of Jewish Diaspora, Sharply Restricts Labor Migrants and Asylum Seekers

A gathering in Tel Aviv for asylum-seeker rights. (Photo: Ben Kelmer/Physicians for Human Rights)

Israel is an immigrant settler society based on an ethnonationalist structure, as defined both ideologically and institutionally. In a very different context than immigrant-receiving societies in Europe and North America, immigration is open to anyone who can prove Jewish ethnicity, but is extremely difficult for non-Jews. Israel, which views itself as the homeland of the Jewish diaspora, characterizes its Jewish newcomers as “returning ethnic immigrants”—in other words, legitimate members of the ethnic Jewish majority.

Embedded in the Law of Return of 1950 is the centrality of the idea of migration as a return of the diaspora. This law created the framework that grants Israeli citizenship to Jews and their children immediately upon immigration. According to the halakha (Jewish law), a Jew is a person who was born of a Jewish mother or has converted to Judaism and who is not a member of another religion. Since the 1970 reform of the Law of Return, the "right of return" has been extended to grandchildren of Jews too, and their nuclear families (even if not Jewish) (see Box 1).

Box 1. The Law of Return

Israel exclusively uses the system of jus sanguinis (law of blood) to determine the citizenship of immigrants and their descendants.

As the Law of Return outlines:

4A. (a) The rights of a Jew under this law …are also vested in a child and a grandchild of a Jew, the spouse of a Jew, the spouse of a child of a Jew, and the spouse of a grandchild of a Jew, except for a person who has been a Jew and has voluntarily changed his religion.

Source: Jewish Virtual Library, “Israel’s Basic Laws: The Law of Return (July 5, 1950,” accessed January 31, 2020. Available online.

Until the end of the 1980s, most of the arriving immigrants in Israel were of Jewish origin, strengthening the Jewish majority vis-à-vis the native Arab population. Since the middle of the 1990s, however, the ethnic composition of the migration flows has changed. Three groups of non-Jewish migrants have arrived in Israel:

- non-Jewish migrants, primarily from the former Soviet Union (FSU) and Ethiopia, arriving under the auspices of the 1970 amendment of the Law of Return

- temporary labor migrants, chiefly from Asia, who were recruited to replace Palestinian workers after the first Intifada (the Palestinian uprising in 1987), and

- asylum seekers from sub-Saharan Africa crossing the southern Egyptian border without authorization since the middle of the 2000s.

Thus, contemporary Israel provides a particularly illuminating setting to examine changes in the ethnic composition of migration flows and the challenges posed by the arrival of nonethnic migrants to an ethnonational state.

This article describes Israeli society and immigration flows under the Law of Return and examines labor migration and the rise in asylum seekers, reviewing the main challenges that have emerged within the last three decades. These challenges affect the modes in which new patterns of immigration interweave with stratification processes along the lines of nationality, ethnicity, and immigration status.

Israeli Society and Immigration Flows under the Law of Return

The Jewish majority is comprised of two major ethnic groups of distinct origin: those of European or American origin, and those of Middle Eastern or North African origin. Yet the most meaningful ethnic split in Israel is between Jews and Arabs. The Arab population constituted 21 percent of Israeli citizens as of 2017. Arab Israelis are disadvantaged relative to Jews in every aspect of life: education, occupational status and earnings, standard of living, and more.

Israel is a society of immigrants and their offspring: 23 percent of the Jewish majority as of 2018 was foreign born, 32 percent was comprised of the second generation (Israeli born to immigrant parents), and 47 percent was third generation (Israeli born to Israeli-born parents). As the self-defined homeland for the Jewish diaspora, Israel is committed to the successful integration of those arriving under the Law of Return. These newcomers not only have privileged access to citizenship and its benefits, but they also have access to specific integration policies and generous programs, including financial assistance during their first year in Israel. Other integration supports include free Hebrew instruction, loans for buying a house, grants for university students, assistance in finding employment, job retraining, and financial support for employers who hire immigrants.

Migration Flows under the Law of Return

The settlement of Jews in Palestine began at the turn of the twentieth century. Since then, Israel’s immigration history has been closely intertwined with the project of nation-state building and the unending conflict between Jews and Palestinians. Political and economic push factors in migrants’ countries of origin rather than pull factors account for most Jewish migration to Israel.

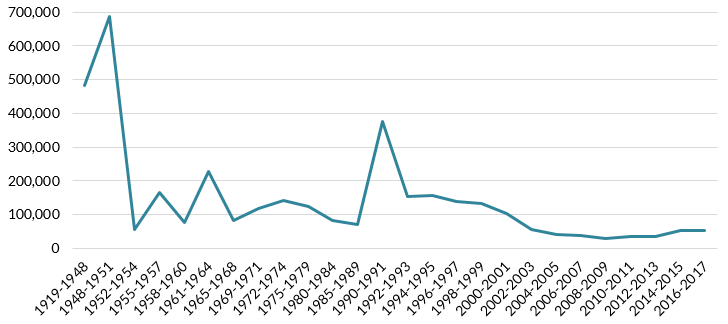

Jewish immigrants arrived in a series of waves: the pre-state era (1880–1948), the first peak of mass immigration shortly after the establishment of Israel (1948–51), and a second peak, mostly from the former Soviet Union after its collapse (1989–95) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Arrival of Immigrants under the Law of Return by Year, 1919-2017

Note: Labor migrants (officially referred to as foreign workers) and asylum seekers (which the state dubs “infiltrators”) are not counted in overall permanent migration statistics, which encompass only those arriving under the Law of Return.

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, “Immigration - Statistical Abstract of Israel, 2018 – No. 69, Table 4.2,” August 16, 2018, available online.

The first wave of Jewish immigrants arrived at the turn of the twentieth century, with more than three-quarters arriving mainly from European countries, particularly Poland, Romania, Russia and its satellites, and Germany. The second wave came shortly after statehood in May 1948. The years 1948-51 marked what sociologist Yinon Cohen called the “demographic transformation” of Israel. It involved two movements: the forced emigration of an estimated 760,000 Palestinians who fled or were expelled, and the immigration of about 678,000 Holocaust survivors as well as Middle Eastern Jews evicted from their homes in Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Yemen. This demographic transformation secured the Jewish majority in the new state, with the proportion of Jews rising from nearly 45 percent in 1947, the year before statehood, to 89 percent at the end of 1951.

Immigration during the 1960s to 1980s was less systematic. It was characterized by a slow but steady stream of immigrants from the Americas, as well as arrivals from South Africa, Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, Ethiopia, and Iran.

Winter 1989 marked a turning point, reversing the declining Jewish flows witnessed during the prior decade. Following the breakup of the Soviet Union, massive numbers of Jews began leaving the Soviet republics to settle in Israel. A country of 4.5 million residents at the beginning of the 1990s, Israel took in nearly 1.1 million immigrants from the former Soviet Union between 1990 and 2018 (about 400,000 of whom arrived between 1990 and 1991).

Immigrants from the former Soviet bloc (both those arriving in the 1990s as well as the earlier cohort from the 1970s) constitute nearly 16 percent of Israel’s general population and 21 percent of its Jewish population. Although immigrants from FSU countries, especially from the European republics, still comprise the bulk of migration flows today, Western Europe (mainly France), North America (chiefly the United States), and South America (Brazil and Argentina) also rank at the top of the list of source countries for flows arriving under the Law of Return.

Table 1. Top 15 Origin Countries for Immigration to Israel under the Law of Return, 2018

Source: Gilad Nathan, International Migration- Israel 2018-2019, The OECD Expert Group on Migration. SOPEMI Annual Report (Emek Hefer, Israel: Ruppin Academic Center, Institute for Immigration and Social Integration, 2019), available online.

Non-Jewish Migration under the Law of Return

Immigration during the 1990s included for the first time an increasing number of immigrants who were not Jewish according to Jewish religious law, but who entered under the 1970 amendment of the Law of Return. Since 1995, non-Jewish immigrants have been labeled "Other" (non-Jews) in official statistics to differentiate them from the native Arab population. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, the "Other" share increased from 1.5 percent of the overall population in 1995 to 4.6 percent in 2017, decreasing the Jewish share from 80.6 percent to 74.5 percent.

Paradoxically, the 1970 amendment to the Law of Return created a new oxymoronic category of “non-Jewish olim” (with olim meaning Jewish immigrants, from the Hebrew word aliya, literally “ascent”). The percentage of non-Jewish olim has risen over time, especially among those from the FSU and Ethiopia. While most FSU immigrants arriving in the early 1990s met the halakha definition of Jewishness, their share dropped from 96 percent in 1989 to 44 percent by 2006. High rates of out-marriage among Jews in the FSU might help account for rising non-Jewish migration. Also, most of the Ethiopians arriving since 1993 were converted Falas Mura, who are not considered Jews according to halakhic law.

Box 2. The Falas Mura

The Falas Mura are the descendants of Beta Israel communities in Ethiopia and Eritrea that converted to Christianity, either voluntarily or by force, during the 19th and 20th centuries. While the Falas Mura view themselves as belonging ethnically to the Beta Israel community, with many practicing Jewish faith rituals and seeking to rejoin the Jewish people in Israel, they are not recognized as Jews under the halakha definition of Jewishness.

Because their ancestors converted out of Judaism to Christianity, the Falas Mura do not enjoy the right of return, but are allowed to immigrate under the 1952 Entry into Israel Law that regulates the right of non-nationals who are not olim to enter and reside in Israel.

Source: Joseph Feit, “Are the Falas Mura Jews? A View from Tradition,” Sh’ma: A Journal of Jewish Ideas, April 2000, www.bjpa.org/content/upload/bjpa/feit/Feit30.pdf.

Non-Jewish migrants arriving under the Law of Return and the Falas Mura are encouraged by the state to convert to Judaism. Yet just 5 percent of FSU migrants have undergone conversion, which is long, difficult, and monopolized by the Orthodox rabbinical authorities. By contrast, rates of conversion are high among Ethiopians, as it is a condition for immigrating to Israel.

Several findings suggest that most non-Jews arriving under the Law of Return are socially integrated. Asher Cohen and Bernard Susser coined the term “sociological conversion” to describe the integration of non-Jewish FSU olim in Israeli society that is not dependent on adopting the Jewish religion but on embrace of the culture, identity, and practices of the Jewish majority at varying paces and degrees.

Non-Jewish Labor Migration

The first noncitizen workers in Israel were Palestinians from the occupied territories (in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank), who came under Israeli military rule after the 1967 Six Day War. Noncitizen Palestinians were recruited for jobs mainly in construction, agriculture, and services. These workers—mostly daily commuters—comprised about 8 percent of the Israeli labor force by the end of the 1980s. As a distinct social group, they were clearly located at the bottom of the Israeli labor market and the ethnic system.

The deterioration of the political and security situation with the first Intifada in the occupied territories in 1987 resulted in a severe labor shortage in construction and agriculture. The entry of Palestinian workers was impeded by periodic strikes organized by the Palestinian leadership and the systematic border closures imposed by the Israeli government as a reaction to attacks. The government’s unwillingness to improve wages and introduce technological changes in construction and agriculture, the increasing demand for housing due to massive immigration flows at the beginning of the 1990s, and rising violence between Palestinians and Israelis all set the stage for the government’s decision in 1993 to recruit overseas labor migrants in sizeable numbers.

Temporary labor migrants are formally recruited mainly for three main sectors: agriculture, construction, and domestic caregiving. Unlike the construction and agriculture sectors, where labor migrants replaced Palestinian workers, the recruitment of foreign workers for the domestic caregiving sector created an entirely new employment niche staffed exclusively by non-nationals. The Long-Term Care Insurance Act, implemented in 1988, marked the first large-scale arrival of caregiving workers. The law permits those in need of geriatric care to hire non-Israeli workers to provide round-the-clock care, allowing the elderly to continue living at home. The Israeli government sets quotas for labor migrants in agriculture and construction (approximately 29,000 workers in each sector in 2019); work permits for non-Israeli caregivers are not capped.

Labor Migration Flows

Caregiving has accounted for an increasing share of overall labor migration, currently representing 60 percent (see Figure 2). The agricultural sector has remained quite stable over the last two decades, accounting for roughly one-fourth of work permits. While in 1996 the construction sector was the largest employer of migrant workers, its share has fallen from 58 percent of all permits to 13 percent.

Figure 2. Number of Legal Labor Migrants in Israel by Sector of Employment, 2010-18

Source: Population, Immigration, and Border Authority (PIBA). “Data on Foreigners in Israel, Table 6,” available online.

About two-thirds of labor migrants come from Southeast Asia, mainly female caregivers from the Philippines, India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. Migrants from Thailand (mostly men) come to work in the agriculture sector and male migrants from China work in the construction sector. (See Table 2.)

Table 2. Labor Migrants by Selected Countries of Origin, 2018

Source: Central Bureau of Statistics, “Statistical Abstract of Israel, No. 70, Table 2.6,” September 26, 2019, available online.

Labor migrants from Europe come mainly from countries in the FSU (14,900 arriving in 2018), particularly from Moldova, with women working in the caregiving sector and men in construction. Another 800 labor migrants came from Romania that year, nearly three-quarters of them women working in caregiving and men working in construction.

Similar to what happens in other countries, the official figures do not reflect the real number of labor migrants in Israel. Many labor migrants arriving with work permits leave their legal employers and work without a permit or do not depart at the end of their contracts, thus residing illegally in Israel. This phenomenon is more accentuated among caregivers, with an estimated 17 percent working in the sector in irregular fashion, as compared to 7 percent in agriculture and 5 percent in construction. Other irregular migrant workers enter the country on a tourist visa, which forbids them to work, and overstay.

About three-quarters in 2019 were from Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia, with another 10 percent from Mexico, Venezuela, Peru, Colombia, and Uruguay. Due to an extensive immigration enforcement campaign and stepped-up deportations, the numbers of irregular migrants decreased from 95,000 in 2011 to 56,000 in 2019.

Labor Migration Policy

Labor migration in Israel is temporary in nature and based on contractual labor, with no path to permanent settlement or citizenship. In order to prevent extended stays, the government does not allow workers to remain for more than 63 months. Furthermore, labor migrants are not permitted to enter with their spouses or any other first-degree relatives, to prevent them from establishing permanent residence or starting a family in Israel. Employers, not migrants, are the ones who receive work permits, thereby maximizing employer and state control over the migrants. The state does not allow residence without a work permit and has a stringent deportation policy permitting the arrest and expulsion of irregular migrants at any time by administrative decree. Migrant workers are exposed to a high degree of regulation and labor market control that employers do not have over citizens, thus creating a precarious noncitizen workforce.

While Israel has progressive laws protecting workers’ rights for all residents, citizen or not, in practice, there is a huge gap between the laws on paper and their implementation. The violation of migrant workers’ social and civil rights owes more to the lack of infrastructure around the laws, compounded by the state’s unwillingness to enforce them. The precarious status of foreign workers confines them to the margins of the Israeli economy and society.

Recruitment of Labor Migrants: From Privatization to Bilateral Agreements

From the outset, the recruitment of foreign workers through official channels has been privatized and conducted through recruiting agencies at origin and destination, enabling profit-seeking private agents to dominate this field. Until 2006, these agents were prohibited from charging the migrants recruitment fees. Since then, agencies have been permitted to collect fees of no more than 3,479 Israeli shekels (about U.S. $1,000) per worker, in addition to travel expenses. Despite these regulations, manpower agencies were charging migrants significantly higher fees—as high as $22,000 for Chinese workers, and averaging $8,720 for Thai agricultural laborers and $6,000 to $7,000 for Filipino, Nepalese, and Sri Lankan care workers, according to a study conducted by the author and a colleague in 2011-12.

To combat these practices, the Israeli government in 2005 began to negotiate and sign bilateral agreements with countries from which workers would be recruited. Yet because of political pressure exerted by the agricultural lobby and manpower agencies in the agriculture sector in Israel and in Thailand, it took until 2010 for the first bilateral agreement to be signed. The Thai agreement was followed by bilateral agreements to recruit migrant workers for the construction sector with Bulgaria (in 2011), Moldova (2012), Romania (2014), Ukraine (2016), and China (2017).

The switch to bilateral agreements resulted from a push by Israeli NGOs and advocacy networks for adoption of international standards and tools in labor migration control. This intervention has been crucial in prompting changes that incorporate international conventions and normative standards in national legislation.

The implementation of bilateral agreements in agriculture and construction eliminated the role of private recruiters, with recruitment now monitored by national offices in Israel and origin countries. As a result, migration costs have declined dramatically. Costs (including travel) now range from $400 for Moldovan migrant workers to $1,500 for Chinese migrants, and $2,100 for Thai laborers (the latter includes a payment of $800 to the manpower agency that provides services to the workers during their stay). Consequently, the debts migrants incur to finance their move have been dramatically reduced, and so has the time needed to repay them. If before the bilateral agreements it took on average 1.5 years to repay the recruitment debt, post-agreement, the time takes on average five months, according to research this author and a colleague did last year.

The same cannot be said for the caregiving sector. While agreements for pilot programs were signed with Nepal (2015) and Sri Lanka (2016), only an estimated 130 migrant workers have arrived under these accords, recruited by government offices. Most labor migration in the caregiving sector is conducted through private recruitment agencies, and migrants still pay exorbitant fees and illegal fees. A bilateral agreement was signed with the Philippines in 2018, but has yet to be implemented due to political instability in Israel (three elections in the last year).

Asylum Seekers

Since the middle of the 2000s, significant flows of sub-Saharan African asylum seekers, mainly from Sudan and Eritrea, have reached Israel through the Egyptian border. Many lived in Cairo after fleeing war and political persecution in their countries. After protestors were shot by Egyptian police during the Mustafa Mahmud demonstration in 2005, many asylum seekers felt Egypt was no longer safe and sought refuge in Israel. In addition, as Libya clamped down on maritime departures from its shores to Europe, migrants looking for alternative routes saw Israel as a destination because it could be reached through the Sinai. Migrants, especially Eritreans, were smuggled through the Sinai desert and were often victims of human trafficking.

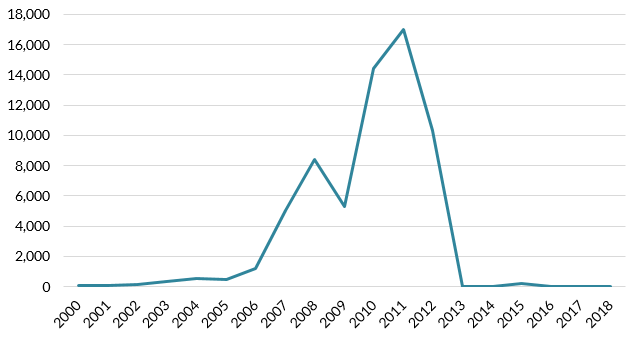

The asylum flows showed a dramatic increase in 2007, but were most marked in 2010-12, when 42,000 asylum seekers arrived (see Figure 3). Since the erection of a fence along the Egyptian border in 2012, only a tiny number have been able to cross the border.

Figure 3. Arrival in Israel of Asylum Seekers from Africa by Year, 2000-18

Source: PIBA, “Data on Foreigners in Israel, Table 2,” updated December 31, 2018, available online.

By the end of 2018, just under 34,000 asylum seekers resided in Israel, with women comprising 17 percent. These numbers do not include the estimated 5,000 to 8,000 children born in Israel to asylum seekers. Seventy-one percent of asylum seekers originate from Eritrea and 20 percent from Sudan, countries known for severe human-rights violations. Most live in the southern neighborhoods of Tel Aviv, but also in impoverished neighborhoods of cities such as Eilat, Arad, and Jerusalem, where labor market demands allow them to find jobs in hotels and restaurants.

Although Israel is a signatory to the 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol, and is a member of the Executive Committee of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the state has failed to create an appropriate legal infrastructure to address asylum conditions. Prior to the arrival of African asylum seekers beginning in the 2000s, Israel had granted refuge to small groups of asylum seekers, from Vietnam (around 400, in 1977 and 1979), Bosnia (84 in 1993), Kosovo (112 in 1999), and in 2000 Southern Lebanese soldiers who cooperated with the Israeli Defense Forces. These cases were exceptional humanitarian cases that did not derive from the legal commitment to the 1951 UN Refugee Convention and did not lead to the creation of an orderly system for determining refugee status.

Asylum seekers in Israel, especially those who are Eritrean and Sudanese, are given temporary group protection status, which grants them immunity from deportation, in accord with the principle of nonrefoulement endorsed by the Refugee Convention. Under this status, until 2013 asylum seekers were not permitted to submit individual applications for asylum and have their case heard. Between 2014 and 2018, 21,000 asylum applications were submitted by sub-Saharan Africans, but recognition rates remain exceptionally low—less than 1 percent.

State policies do not consider the needs of asylum seekers and instead deal mainly with forced geographical allocation, detention (at the Saharonim and Holot facilities near the border with Egypt), and deportation and coerced “voluntary” departure.

In order to avoid the concentration of asylum seekers in the central part of the country, the government set up “Gedera-Hadera” geographical restrictions in February 2008. This restriction demarcated a prohibited area for residence and employment north of Gedera or south of Hadera, leaving the central part of the country off limits. This policy created immense social and economic pressure on Israel’s peripheral cities, and after complaints from mayors of these communities, the restrictions were cancelled in July 2009.

Asylum seekers are defined by the Israeli state as “infiltrators,” a term that has two meanings. The first regards asylum seekers as economic migrants instead of genuine refugees. Therefore, under this view, they do not deserve to be treated as asylum seekers who can make legitimate claims for refuge in Israel. The second use is political and related to the border crossings in the 1950s of Palestinian Fedayeen who attempted to enter the country to commit terrorist attacks. Asylum issues have been closely linked with Israeli security concerns because of the fear that the recognition of African refugees “will open up the Pandora’s box of Palestinian refugees’ claims for territory, compensation, and the right of return,” argued Yonathan Paz.

The issue of asylum touches deeply on the perception of the existence of different degrees of membership and the relative position assigned to ethnic and nonethnic migrants in Israeli society. Speaking of the deportation of asylum seekers from South Sudan in 2012, Israeli Interior Minister Eli Yishai said: “In having to choose between being called ‘enlightened and liberal’ but not having a Jewish and Zionist state, and being called ‘endarkened and racist’ but being a proud citizen, I choose the second option. The era of slogans has ended, now the era of actions has begun."

Asylum Policy

The legal basis upon which the state determines its policy towards sub-Saharan asylum seekers is the 1954 Anti-Infiltration Law, originally designed to stop the entry of Palestinians and other Arab nationals in the wake of the 1948 war—and particularly to prevent the re-entry of Palestinian refugees. Intended to secure Israel’s right to protect itself, the law authorizes severe measures against individuals from enemy states who enter Israel unlawfully.

The Netanyahu government in 2012, 2013, and 2014 attempted to introduce several amendments to the Anti-Infiltration Law that would allow the state to hold asylum seekers in administrative detention, without trial or even indictment. The Israeli Supreme Court of Justice quashed the first two amendments “for violating the constitutional rights to liberty, and human dignity to which every person is entitled in Israeli law." Regarding the 2014 amendment, the court ordered the shortening of the detention period, but did not rule it out entirely as a measure to discourage unauthorized migration.

Asylum seekers are denied welfare and social rights, except for emergency health care. They do not have the right to work in Israel. Yet there is no enforcement against employers who hire asylum seekers. Therefore, de facto, many asylum seekers work in Israel, especially in hotels, restaurants, and domestic work.

Beyond formal labor market restrictions, legislation enacted in recent years prohibits asylum seekers from sending money home. Employers are required to deduct 20 percent of asylum seekers’ salary and deposit it in a separate account to which they are obliged to deposit a further 16 percent of the salary. These funds are to be released only upon the asylum seekers’ departure from Israel. This effectively reduces asylum seekers' disposable income and further exacerbates their precarious status in Israeli society.

These and other laws and policies have hidden and damaging effects on asylum seekers' lives. Their uncertain and liminal status in Israel affects all aspects of their lives, such as labor market opportunities, access to and use of health services, family dynamics, and community organization. As prospects for the regularization of their status are dim, there has been a dramatic decline in the number of asylum seekers residing in the country: from 52,961 in 2013 to 33,627 by the end of 2018. Approximately 12,700 asylum seekers departed under a so-called voluntary repatriation program and many others were granted refugee status in countries such as Canada, Sweden, the Netherlands, and the United States.

After launching a campaign of forced deportation contested by civil society, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in 2018 announced that an agreement had been reached with UNHCR. Under the deal, the UN agency agreed to resettle 16,250 asylum seekers to Western countries; in exchange, the remainder would be allowed to remain in Israel with work authorization, with the government committing to relocating most of them to other areas of the country. However, in response to a right-wing backlash, Netanyahu suspended the deal seven hours after it was announced and later cancelled it. The refusal to grant legal status and rights leaves asylum seekers in a permanently vulnerable and precarious position, in the shadow of the continuous threat of detention and deportation.

A De Facto Multiculturalist Society without Prospect for Multiculturalism?

The changing ethnonational composition of post-1990 immigration flows poses new challenges to the Israeli state and society, one of which is dealing with non-Jewish immigrants and relatives who arrive under the Law of Return. This new status of non-Jewish olim has substantial stratifying effects on the materialization of various rights in the context of an ethnonational state. Such immigrants face difficulties over rights such as marriage, burial, and family unification, due to the monopoly of religious institutions over family and burial issues. Non-Jews marrying Jews in Israel, for example, must bypass the official institutions, sometimes traveling abroad to formalize their union. Non-Jewish burial grounds have only recently been introduced, and many immigrants have experienced great difficulty when seeking to lay their loved ones to rest. Non-Jewish citizens also face difficulties in seeking citizenship for their non-Jewish spouses, children, or parents. This inability to sponsor the immigration of an immediate relative is a source of great distress for many. Given that Israel is unlikely to separate religion and state in the near future, the chances of full legal and political equality for the new (non-Jewish) immigrant population seem slight.

The presence of migrant workers and asylum seekers also challenges the basic definition of Israeli society as an ethnonational polity that encourages the permanent settlement of Jewish immigrants and discourages that of non-Jewish migrants. The migration regime is highly exclusionary regarding non-Jews not covered by the Law of Return amendment; it also denies any possibility of incorporation for foreign workers and asylum seekers. The unwillingness to accept non-Jewish immigrants is expressed through exclusionary immigration policies (especially the limitations of family reunion and refusal to provide residence status), restrictive naturalization rules, and a double standard: an exclusionary model for non- Jews vs. an "acceptance-encouragement" model for Jews. In that sense, Israel’s migration policy for non-Jews reflects official concern that a changing ethnoscape could threaten its Jewish character.

These exclusionary attitudes and policies towards nonethnic migrants should be understood within the general context of an ethnonational state like Israel. The ethnic-religious nature of nationalism (and incorporation regime), the absence of egalitarian rules and citizenship for non-Jews, and a highly restrictive naturalization policy all make Israel a de facto multicultural society with few prospects for multiculturalism.

Sources

Afeef, Karin Fathimath. 2009. A Promised Land for Refugees? Asylum and Migration in Israel. New Issues in Refugee Research, Working Paper No. 183, Geneva, UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Available online.

Central Bureau of Statistics. 2018. Population – Statistical Yearbook for Israel 2018 – No. 69, Population, by Population Group. Available online.

---. 2019. Statistical Abstract of Israel 2019 – No. 70. Last updated September 19, 2019. Available online.

Cohen, Asher and Bernard Susser. 2009. Jews and Others: Non-Jewish Jews in Israel, Israel Affairs 15 (1): 52-65.

Cohen, Yinon. 2002. From Haven to Heaven: Changing Patterns of Immigration to Israel. In Challenging Ethnic Citizenship: German and Israeli Perspectives on Immigration, 36-56, eds. D. Levy and Y. Weiss. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books.

DellaPergola, Sergio. 1998. The Global Context of Migration to Israel. In Immigration to Israel: Sociological Perspectives, 51-92, eds. Elazer Leshem and Judith T. Shuval. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Fisher, Netanel. 2013. A Jewish State? Controversial Conversions and the Dispute over Israel’s Jewish Character, Contemporary Jewry 33 (3): 217-240.

Gershon, Shafir and Yoav Peled. 2002. Being Israeli: The Dynamics of Multiple Citizenship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guthmann, Anat and Sigal Rozen. 2019. Immigration, Detention in Israel 1998-2018. Tel Aviv: Hotline for Refugees and Migrants. Available online.

Kalir, Barak. 2015. The Jewish State of Anxiety: Between Moral Obligation and Fearism in the Treatment of African Asylum Seekers in Israel, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (4): 580-98.

Kemp, Adriana and Rebeca Raijman. 2004. “Tel-Aviv Is Not Foreign to You”: Urban Incorporation Policy on Labor Migrants in Israel, International Migration Review 38 (1): 26-52.

---. 2008. “Workers” and “Foreigners”: The Political Economy of Labor Migration in Israel. Jerusalem: Van-Leer Institute and Kibbutz Hamehuhad. (In Hebrew)

Mesgena, Hadas Yaron and Oran Ramati. 2017. Where Time Stands Still: Holot Detention Facility and the Israeli Anti-Infiltration Law, Hagira 7: 67-82. Available online.

Nathan, Gilad. 2019. International Migration- Israel 2018-2019: The OECD Expert Group on Migration SOPEMI Annual Report. Emek Hefer, Israel: Ruppin Academic Center, Institute for Immigration and Social Integration. Available online.

Paz, Yonatan. 2011. Ordered Disorder: African Asylum Seekers in Israel and Discursive Challenges to an Emerging Refugee Regime, Research Paper No. 205. Geneva: UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Available online.

Population, Immigration and Border Authority (PIBA). 2019. Data on Foreigners in Israel. Accessed January 23, 2020. Available online. (In Hebrew)

Prashizky, Anna and Larissa Remennick. 2014. Gender and Cultural Citizenship among Non-Jewish Immigrants from the Former Soviet Union in Israel, Citizenship Studies 18 (3-4): 365-83.

Raijman, Rebeca. 2010. Citizenship Status, Ethno-National Origin and Entitlement to Rights: Majority Attitudes towards Minorities and Immigrants in Israel, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (1): 87-106.

Raijman, Rebeca and Anastasia Gorodzeisky. 2016. We and the Others: Majority Attitudes towards Non-Jews in Israel. In Handbook of Israel: The Major Debates vol.1, 324-44, eds. Eliezer Ben-Rafael (coordinator), Julius H. Schoeps, Yitzhak Sternberg, and Olaf Glöckner. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Raijman, Rebeca and Adriana Kemp. 2007. Labor Migration, Managing the Ethno-National Conflict, and Client Politics in Israel. In Transnational Migration to Israel in Global Comparative Context, 31-50, ed. Sarah S. Willen. Plymouth, UK: Lexington Books.

---. 2010. The New Immigration to Israel: Becoming a De-Facto Immigration State in the 1990s. In Immigration Worldwide, 227-43, eds. Uma A. Segal, Doreen Elliott, and Nazneen S. Mayadas. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

---. 2016. The Institutionalization of Labor Migration in Israel, Arbor 192 (777): a289.

Raijman, Rebeca and Nonna Kushnirovich. 2012. Labor Migration Recruitment Practices in Israel. Jerusalem: Center for International Migration and Integration. Available online.

---. 2019. The Effectiveness of the Bilateral Agreements: Recruitment, Realization of Social Rights, and Living and Employment Conditions of Migrants Workers in the Agriculture, Construction, and Caregiving Sectors in Israel: 2011-2018. Emek Hefer and Jerusalem: Ruppin Academic Center, Center for International Migration and Integration, and Population and Immigration Authority. Available online.

Raijman, Rebeca and Yanina Pinsky. 2011. Non-Jewish and Christian: Feelings of Discrimination and Social Distance of FSU Migrants in Israel, Israel Affairs 17 (1): 125-41.

---. 2013. Religion, Ethnicity and Identity: Former Soviet Union Christian Immigrants in Israel, Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (11): 1687-1705.

Remennick, Larissa. 2007. Russian Jews on Three Continents: Identity, Integration and Conflict. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

---. 2003. Immigration and Ethnicity in Israel: Returning Diasporas and Nation Building. In Diasporas and Ethnic Migrants: Germany, Israel and Post-Soviet Successor States in Comparative Perspective, eds. Rainer Muenz and Rainer Ohliger. London: Frank Cass.

Shapira, Assaf. 2019. Israel’s Citizenship Policy since the 1990s—New Challenges, (Mostly) Old Solutions, British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 46 (4): 602-21.

Weiss, Yfaat. 2002. The Golem and its Creator, or How the Jewish Nation-State Became Multiethnic. In Challenging Ethnic Citizenship: German and Israeli Perspectives on Immigration, 82-104, eds. Daniel Levy and Yfaat Weiss. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Ziegler, Reuven. 2015. No Asylum for “Infiltrators”: The Legal Predicament of Eritrean and Sudanese Nationals in Israel, Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Law 29 (2): 172-91. Available online.