You are here

National Guard Heads to Southern Border Amid Differing Reality from Earlier Deployments

Arizona National Guard troops serve along the Southwest border in 2010. (Photo: Jon Soucy/U.S. Army)

Opening a new front in his campaign to crack down on illegal immigration, President Donald Trump in early April 2018 called for the deployment of up to 4,000 National Guard troops to the U.S.-Mexico border. The President seized on a seasonal uptick in illegal crossings and reports of a “caravan” of Central American migrants traveling toward the border in announcing his decision. While this is not the Guard’s first border deployment, it is unique given the absence of a clearly articulated need for troops, at a time when overall border apprehensions are near historic lows. Further, the move fails to take into account the changing nature of migration to the U.S. border, and has raised concerns about the potential foreign policy implications of appearing to involve the military in immigration enforcement.

Previous presidents, including Barack Obama and George W. Bush, directed the National Guard—a reserve division of the U.S. Army and Air Force that serves both federal and state missions, and typically must be activated by states—to deploy to the border in response to surges in violence, drug trafficking, or apprehensions of unauthorized migrants. However, these conditions are not present today, and President Trump’s order seems to be primarily driven by political and public relations concerns. The decision came just after the President signed the fiscal year (FY) 2018 omnibus spending bill, sharply criticizing it for lacking substantial funding for his proposed border wall, a key campaign promise. And unlike in previous deployments, neither state officials nor members of Congress from border states requested the placement of troops.

Though none had sought the deployment, all four states along the U.S.-Mexico border agreed to activate National Guard troops, who will be used in support roles and not in law enforcement. Texas immediately sent 250 members, and Governor Greg Abbott said he wanted to increase this number to 1,000; Arizona agreed to send 300; and New Mexico initially sent 80 but expects to deploy 250. California agreed to deploy 400 troops, though there was a brief dispute between the state and the Trump administration over the terms of their mission. In a statement, California Governor Jerry Brown said the troops would join an ongoing project to combat transnational crime and would not enforce immigration laws.

As of this writing, the deployment orders only extend through September 30, but the President has said he wants the troops to remain until the border wall is built.

History of National Guard Border Deployment

In his order to deploy the National Guard, Defense Secretary James Mattis used his authority under 32 U.S.C. 502(f), a statute allowing governors, with the approval of the President or the Defense Secretary, to order the Guard for full-time work in activities related to homeland defense. In this status, the Guard troops remain under the command of their respective states but are funded by the federal government.

Despite some reports to the contrary, when deployed under Title 32, the National Guard is in state, not federal service, and thus not subject to the Posse Comitatus Act. This 1878 law prohibits the use of the Army and Air Force to execute domestic laws, except where expressly authorized by the Constitution or Congress. However, the order issued by the Defense Secretary specified that Guard personnel “will not perform law enforcement activities or interact with migrants” without the approval of the Department of Defense, and that “arming will be limited to circumstances that might require self-defense.”

President Trump is not the first president to order deployment of the National Guard to the U.S.-Mexico border. In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson sent the Guard to respond to crossborder crime resulting from the Mexican Civil War. A small number of troops were stationed at the border under Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton to help build infrastructure.

Amid particularly high apprehensions of unauthorized border crossers, President George W. Bush in May 2006 called for the deployment of up to 6,000 National Guard troops to the border. Under Operation Jump Start, the troops relieved Border Patrol agents from performing duties unrelated to law enforcement, such as vehicle and facility maintenance, control room operation, and administrative support, allowing U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to focus on recruiting and training new agents. The operation ended in July 2008 once the number of agents had increased by almost 40 percent, to 16,700 agents from approximately 12,000 in May 2006. Over the course of two years, the deployment cost the U.S. government a total of $1.2 billion, according to a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report.

In May 2010, during a period of relatively low apprehensions but concern about border violence, including the killing of a prominent Arizona rancher, President Barack Obama mobilized 1,200 National Guard troops. The deployment came amid violence along the Mexican side of the border due to the Mexican government’s confrontations with powerful drug cartels and smuggling organizations. Mexico estimates that more than 15,000 people died in drug-related violence in 2010.

The National Guard’s duties were limited to surveillance and intelligence work to help Border Patrol agents track down immigrants. Slightly more than a year later, the administration reduced the number of troops assigned to the border from 1,200 to 300. Though the total cost is not publicly available, the first year of deployment cost $110 million, according to the GAO.

Also during the Obama administration, though not the result of a federal order, Texas Governor Rick Perry in 2014 deployed 1,000 National Guard members to the border to help process the record numbers of unaccompanied children entering the United States. State lawmakers said in 2017 that the total cost of the deployment, including National Guard and Texas Military Forces expenses, was nearly $63 million.

Border Security: Then vs. Now

Compared to 2006 and 2010, today’s border reality differs according to several key metrics.

Apprehensions

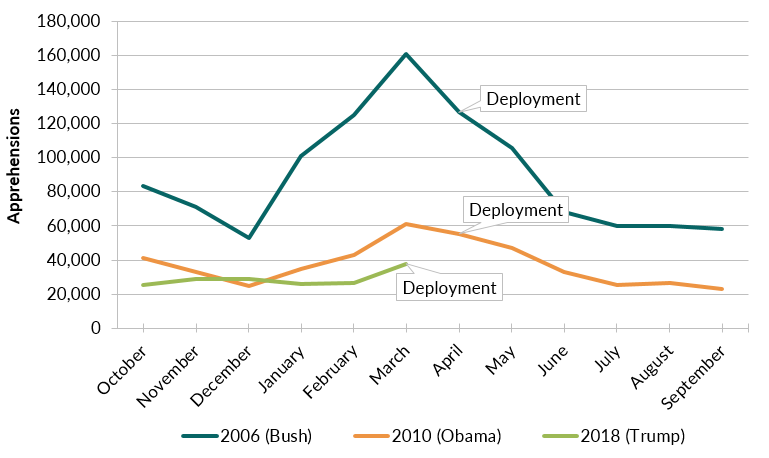

In FY 2017, border apprehensions dropped to the lowest levels seen since 1971. While they have trended slightly upward in FY 2018, apprehensions remain historically low. Other than in FY 2015-17, fewer people were apprehended in March 2018 than in March of any other year going back to FY 2000, including the years in which Presidents Obama and Bush ordered the National Guard to the border (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Southwest Border Apprehensions by Month, Fiscal Years (FY) 2006, 2010, and 2018

Note: FY 2018 data, which span October 2017 through March 2018, cover the first half of the fiscal year.

Sources: U.S. Border Patrol, “Total Illegal Alien Apprehensions By Month, 2000-2017,” accessed April 18, 2018, available online; U.S. Customs and Border Protection, “Southwest Border Migration FY 2018,” updated April 4, 2018, available online.

There were 32 percent fewer apprehensions in March 2018, the month before President Trump’s order, than in the month prior to President Obama’s 2010 order, and 70 percent fewer compared to the month before President Bush’s 2006 mobilization.

In addition, the composition of apprehended migrants is very different today. Those arriving at the border now are more likely to be asylum seekers from Central America, many of whom turn themselves in to agents or at official ports of entry rather than trying to cross without detection. In FY 2017, 58 percent of apprehended border crossers were from countries other than Mexico, compared to 11 percent in 2010 and 9 percent in 2006. And asylum applications are up by more than 900 percent since the National Guard was last deployed: In FY 2017, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) made nearly 80,000 credible fear determinations in asylum cases, compared to fewer than 8,000 in 2010.

While Trump has indicated that he recognizes the different composition of today’s border flows, he has not explained how the National Guard will help in these particular circumstances. Instead, Trump’s advisers said that he would seek legislation to block asylum seekers, including unaccompanied children, from entering the United States. To process arriving immigrants, the administration has dispatched additional asylum officers, immigration judges, and prosecutors.

Number of Border Patrol Agents

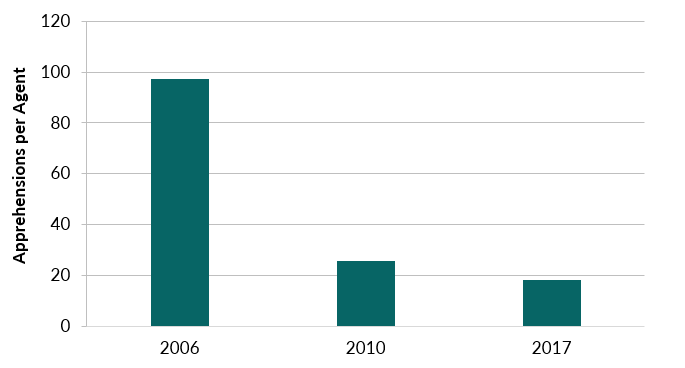

Today, even without the National Guard, the number of Border Patrol agents is more than 50 percent higher than in 2006, when Bush called in the Guard amid significantly higher apprehensions. In fact, the average number of apprehensions per agent in FY 2006 was about 97, while in FY 2017 it was roughly 18.

Figure 2. Average Apprehensions per Border Patrol Agent, FY 2006, 2010, 2017

Sources: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) analysis of U.S. Border Patrol, “Total Illegal Alien Apprehensions By Month, 2000-2017,” accessed April 18, 2018, available online; United States Border Patrol, “Border Patrol Agent Staffing by Fiscal Year,” 1992-2017, accessed April 18, 2018, available online.

Broader Political Context

The factors that triggered prior deployments—the spike in apprehensions in 2006, and violence in 2010—pushed governors and state military officers of Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas to request placement of the Guard. In 2018, while some governors have responded enthusiastically to President Trump’s decision, none sought a deployment.

Pressure from Congress also precipitated the earlier deployments. Many Republicans had criticized Bush for paying insufficient attention to the border and immigration enforcement. He also pursued the deployment partly in the hope that it would win him enough congressional support to pass comprehensive immigration reform.

Before Obama made his decision, he met with Senate Republicans who had backed a measure introduced by Arizona Republican Senators John McCain and Jon Kyl to deploy up to 6,000 National Guard troops.

Meanwhile, Trump and Congress have repeatedly butted heads on border security. There has been little appetite on Capitol Hill to appropriate the $20-25 billion dollars estimated necessary to build the border wall. And though the White House demanded $1.6 billion for the wall in the most recent omnibus spending bill, Congress instead gave the administration $1.375 billion for fencing, specifying that it could not be used for walls.

Foreign Policy Implications

There have also been concerns about the foreign policy implications of sending the Guard to the border with Mexico—a U.S. ally and partner in many areas, including criminal and immigration enforcement. Though the federal government assured Mexico that Guard units would not be armed, the deployment prompted the Mexican Senate to demand that President Enrique Peña Nieto suspend cooperation with the United States on border security, until Trump decides to “conduct himself with the civility and respect that the Mexican people deserve.” Peña Nieto subsequently gave a speech condemning Trump’s decision and ordered a review of all forms of cooperation with the United States, ranging from border security and migration to trade and the fight against drugs.

This is not the first time during the Trump administration that Mexico has had to be assured that U.S. immigration enforcement activities are not military operations. In February 2017, Trump called his administration’s moves to deport unauthorized immigrants a “military operation,” prompting former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and former Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly to assure their Mexican counterparts that there was in fact no plan to use the military to enforce immigration laws.

However, Mexico has since taken a similar action along its own southern border, perhaps in response to the U.S. move and the attention that a “caravan” of more than 1,200 Central American migrants has received. On April 10, Mexican Interior Minister Alfonso Navarrete Prida announced that he would direct an unknown number of federal police officers to the Mexico-Guatemala border. The move appears to be symbolic, as these agents are already active in immigration enforcement activities in the country’s southern border region.

Considering Trump’s standoff with Congress over the border wall, and his determination to keep the Guard at the border until his signature initiative is realized, the Guard’s posting may be indefinite, no matter the lack of obvious need for their presence or its potential implications for the country’s relationship with Mexico.

- California Governor’s General Order and terms for deploying the California National Guard

- GAO report on costs and benefits of an increased Department of Defense role at the Southwest border

- National Guard fact sheet on Operation Jump Start

- Homeland Security Secretary’s statement on the Central American “caravan”

- Presidential Memorandum on securing the southern border

- Presidential Memorandum on ending “catch and release”

National Policy Beat in Brief

Federal Judge Orders Potential Resumption of DACA. A federal judge in the District of Columbia has ruled that the Trump administration’s process to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program was unlawful, but has given the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) 90 days to better explain its reasoning behind ending the program. If DHS fails to convince the judge, the order will become final and DHS will have to resume the program in its entirety, including accepting new applications. The order came as a result of two cases, NAACP v. Trump and Princeton v. United States. While this is the third judge to order the government to continue the Obama-era program, the order is the first that would require the government to consider new applicants.

President Trump in September 2017 began a phaseout of DACA, which provides work authorization and protection from deportation to unauthorized immigrants brought to the United States as children. Since then, Congress has considered several legislative measures to make the program permanent or provide a path to legal status for DACA recipients, but none have come to fruition. The two other cases ordering the government to continue the program are currently on appeal before the Ninth and Second Circuit Courts of Appeals.

- U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia order in NAACP v. Trump and Princeton v. United States

- Migration Policy Institute Data Tools on DACA

Commerce Department Adding Question on Citizenship to 2020 Census, States Sue. The U.S. Commerce Department announced it will add a question on citizenship to the 2020 Census. The change comes at the request of the Trump administration and was immediately attacked by experts and advocacy groups, who expressed concern that including the question would result in a substantial undercount by dissuading immigrants, particularly unauthorized immigrants, from taking part in the Census. A resulting undercount could affect the number of congressional seats designated to each state and allocation of certain federal funds. The Commerce Department said it weighed this concern and found that the need for accurate citizenship data outweighed fears about a lower response rate.

The decision prompted a swift backlash. California immediately challenged the administration’s decision in federal court, and a group of 17 states and seven cities, led by New York State, later filed a separate lawsuit. The lawsuits allege that the addition of the question undermines the constitutional requirement that each person in the country be counted in a decennial census.

- New York Times article on the addition of the citizenship question

- U.S. Commerce Department press release announcing the addition of the citizenship question

- Commerce Department memo directing the Census Bureau to add the question

- Complaint in State of New York et al. v. Department of Commerce et al.

- Complaint in State of California v. Ross

Justice Department Creates Quotas for Immigration Judges. The Justice Department set performance metrics for immigration judges as part of a broader effort to speed up deportations and shrink the backlog of immigration cases. Judges now must meet new measures to obtain a “satisfactory” rating, such as clearing at least 700 cases per year and having fewer than 15 percent of their decisions overturned on appeal. Critics of the move, including the National Association of Immigration Judges, warned that the metrics could undermine judicial independence and erode due process. At the end of February 2018, almost 685,000 immigration cases were pending, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) at Syracuse University.

- Executive Office for Immigration Review memo outlining the performance metrics

- Wall Street Journal article on the quotas

Justice Department Halts Legal Program for Those in Deportation Proceedings. The Justice Department announced that it would suspend the Legal Orientation Program for detained immigrants in removal proceedings, pending a substantive review of the program’s cost-effectiveness. Launched in 2003 to provide support to immigrants who lack legal representation, the program is run by the nonprofit Vera Institute of Justice, which receives federal funding. Vera Institute employees and volunteers conduct information sessions for detained immigrants and help connect them with lawyers. In 2017, the program served more than 53,000 immigrants.

The Justice Department says the temporary suspension is necessary to “conduct efficiency reviews which have not taken place in six years." Advocates argue the move will curtail the due-process rights of detained immigrants, the vast majority of whom navigate the immigration court system without an attorney.

- Justice Department description of the Legal Orientation Program

- Vera Institute statement on program suspension

- NPR article on the suspension

Supreme Court Strikes Down Criminal Ground for Deportation. The Supreme Court struck down a provision of immigration law that allowed the government to deport lawful permanent residents (LPRs, or green-card holders) and nonimmigrants who commit certain crimes, ruling it unconstitutionally vague. In the case, which began during the Obama administration, the government sought to deport green-card holder James Dimaya, arguing his residential burglary conviction constituted a “crime of violence” and made him deportable. The Supreme Court struck down one of the definitions of “crime of violence” for being too vague, ruling it violated Dimaya’s due-process rights.

The vote was 5 to 4, with the swing vote cast by Trump appointee Neil Gorsuch—who surprised some by siding with four liberal justices. However, others have argued that his vote was not a surprise given his prior positions on vagueness of statutes.

DHS and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) released statements opposing the decision, claiming it limits the government’s ability to deport some types of criminals. The government may still deport legal immigrants and visitors for committing crimes not covered by the court’s decision.

- Supreme Court order in Sessions v. Dimaya

- Washington Post article on the decision

- DHS Press Secretary statement on Dimaya

- ICE Deputy Director statement on the court ruling

ICE Conducts Largest Workplace Operation in Recent History. On April 5, ICE officers arrested 97 people at a meatpacking plant in rural Tennessee, in what appears to be the largest worksite enforcement operation since the George W. Bush administration. Working in conjunction with the Tennessee Highway Patrol and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), officials arrested 86 individuals on suspicion of unlawful presence and issued criminal charges against another 11. Of the former, 32 were released and 54 are being held in detention centers.

According to the IRS, the company that owns the plant has evaded paying millions of dollars in taxes. The operation in Tennessee comes after recent worksite operations carried out in January against dozens of 7-Eleven stores suspected of hiring unauthorized workers. ICE leadership promised to radically scale up the scope and frequency of its workplace enforcement actions in 2018.

- Associated Press article on the enforcement operation

Court Orders DHS to Provide Notice of One-Year Asylum Filing Deadline. A federal district court in Seattle ruled that DHS must appropriately notify certain immigrants of their deadline to apply for asylum. Under U.S. immigration law, individuals have one year from the time they enter the United States to file an asylum application. Unauthorized immigrants detained at the border are often released and ordered to appear in immigration court; however, many are never informed about the asylum filing deadline or that they may need to apply before their court hearing, which as a result of backlogs, could be scheduled more than a year later.

The federal judge ordered DHS to begin providing information about the deadline to all asylum seekers within 90 days of their release, and said DHS must accept late applications of individuals not previously given notice of the deadline.

- U.S. District Court Western District of Washington at Seattle order in Mendez-Rojas et al. v. Johnson et al.

- Associated Press article on the case

ICE to Detain Pregnant Women. ICE announced it would begin detaining pregnant women up to their third trimester. The change reverses an Obama administration policy issued in August 2016, which said that “absent extraordinary circumstances or the requirement of mandatory detention, pregnant women will generally not be detained by ICE.” The new internal memo, released in December 2017, reversed the policy, asserting that ICE will detain pregnant women unless “special factors” warrant otherwise. The memo clarified, however, that women in the third trimester will generally be released.

The move is consistent with the Trump administration’s efforts to prioritize detaining individuals in removal proceedings. Immigration advocates and some politicians condemned the new policy, calling it “inhumane” and “cruel and unusual.” ICE Deputy Executive Associate Director Philip Miller claimed that the period between the memos was intended to allow ICE to build its capacity to detain pregnant women, and that it now must detain those women in the same way it detains anyone else.

- ICE memo describing the new pregnant detainee policy

- The Hill article on the new detention policy

- 2016 ICE memo describing the now-defunct pregnant detainee policy

Court Prevents Office of Refugee Resettlement from Blocking Abortions. On March 30, a federal district judge in Washington, DC blocked an Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) policy that inhibited detained unaccompanied immigrant minors from accessing abortions. Officials from ORR, which takes temporary custody of unaccompanied immigrant children, were instructed under the now-blocked policy to discourage girls from seeking abortions by taking them to anti-abortion resource centers and declining to transport them to abortion clinics. In Garza v. Hargan, Judge Tanya S. Chutkan of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia found that this policy violated the Constitution because it placed “undue burden” on a woman’s right to an abortion. The judge issued a preliminary injunction on the ORR policy pending a full hearing in several months.

- U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia order in Garza v. Hargan et al.

U.S. Travel Ban Lifted for Chad, Remains for Seven Other Countries. After conducting a six-month review of security standards, the Trump administration lifted the U.S. travel ban on nationals of Chad. A presidential proclamation stated that Chad had taken steps to make its passports more secure and had improved information sharing on known or suspected terrorists.

The administration added Chad to the third iteration of its travel ban in September 2017, after courts struck down the first two versions. Nationals of seven countries are still subject to the ban: Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela (limited to certain government officials), and Yemen. The U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments on the travel ban’s legality on April 25, with a decision expected in June.

- Presidential proclamation terminating entry restrictions for nationals of Chad

- Reuters article on the decision to remove Chad from the travel ban

State Department Proposes Regulations Expanding Information Required for Visa Applications. The State Department proposed a new regulation that would require most visa applicants to submit up to five years of social media information. Previously, the State Department only scrutinized the social media accounts of applicants who had traveled or lived in parts of the world with high levels of terrorist activity. Under the new policy, the State Department would require almost all visa applicants to hand over records from their social media accounts for “identity resolution and vetting purposes.” The proposed rule has been posted on the Federal Registry for 60 days of public comment, after which the Office of Management and Budget will decide whether to permit implementation.

- Proposed rule for nonimmigrant visas

- Proposed rule for immigrant visas

- Associated Press article on proposed rule

U.S. Expands Program Collecting Biometric Data of Arrested Migrants in Mexico. The U.S. government intends to expand a cooperative agreement with Mexico through which Mexico’s National Migration Institute (Instituto Nacional de Migración) shares data on migrant detainees with DHS. Officially implemented in 2014, the program operates at two detention centers in Mexico, and provides biometric data to DHS on people who may potentially arrive in the United States. According to U.S. officials, the program is set to expand in the coming months to detention centers in Tijuana, Mexicali, and Reynosa along the U.S.-Mexico border. Some officials worry, however, that increasing tensions between the Trump administration and Mexico could put the cooperative program in jeopardy.

- Washington Post article on the program

H-1B Visa Cap for Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 Reached within Five Days. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) announced it had received enough visa petitions to reach the annual statutory cap of 85,000 high-skilled temporary H-1B visas within five days of first accepting petitions on April 2. Within those five days, USCIS received 190,098 petitions, and will use a computer-generated lottery to select the 85,000 petitions to be considered for adjudication.

This is the sixth consecutive year that demand for H-1B visas outstripped supply within the first week that applications were accepted. However, H-1B applications decreased for the second year in a row, prompting some to suggest that the Trump administration’s looming changes to the H-1B program may have dampened employer interest. The administration has ramped up scrutiny for H-1B visa applications, and has announced several upcoming changes, including redefining eligible jobs.

- USCIS news release on the FY 2019 H-1B cap

- Migration Policy Institute brief on the H-1B visa program

Administration Ends Protection Program for Nationals of Liberia, and Potentially Nepal. President Trump declined to extend a protection program for Liberian nationals, giving recipients one year to exit the United States. Due to armed conflict and civil unrest, Liberia was originally designated for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) in 2002 but the designation ended in 2007 after country conditions improved. Since then, former Liberian TPS holders have been protected from deportation under Deferred Enforced Departure (DED), which offers work authorization and protection from deportation, benefits similar TPS. Because of the President’s announcement, Liberians who do not have a separate legal basis to remain in the country past March 31, 2019 will become subject to deportation and lose work authorization.

On April 25, the administration is due to decide whether or not to extend TPS for Nepal. The country was designated for TPS in June 2015 after a severe earthquake hit the country. Between 9,000 and 15,000 TPS holders from Nepal live in the United States.

- Presidential Memorandum on ending DED for Liberians

- USCIS information page on TPS for Nepal

- MPI Source article on TPS

State Policy Beat in Brief

Iowa Enacts Law Prohibiting Sanctuary Cities. On April 10, Iowa Governor Kim Reynolds signed a bill that prohibits cities and counties from restricting or discouraging cooperation with federal immigration authorities and mandates the withholding of state funds from those that do. The law is designed to prevent policies like a 2017 Iowa City resolution, which barred the use of local resources to enforce immigration laws in most cases. Republican legislators who voted for the state law said it will enhance public safety, while opponents argued it would undermine safety by discouraging immigrants from cooperating with local authorities. The Iowa bill comes as the Trump administration has been attempting a broader crackdown on sanctuary jurisdictions.

- Des Moines Register article on the Iowa law

- Cedar Rapids Gazette article on the Iowa City resolution, including text of the resolution

- MPI Source article on sanctuary cities

Arizona Supreme Court Rules DACA Holders Ineligible for In-State Tuition. The Arizona Supreme Court ruled April 9 that state universities and community colleges are not permitted to offer in-state tuition rates to DACA recipients. The ruling upheld a 2017 appeals court decision, which held that schools could not offer in-state tuition because Arizona had not passed legislation explicitly permitting it; DACA recipients will now have to pay full tuition. Some DACA recipients may still be able to access lower rates by taking advantage of an Arizona Board of Regents policy granting a tuition discount to nonresidents who attended Arizona high schools.

- Arizona Republic article on the court decision

Virginia Governor Vetoes Bill Prohibiting Sanctuary Cities. Virginia Governor Ralph Northam vetoed a bill that would have banned cities and counties in Virginia from restricting cooperation with ICE. The bill, proposed by Republican Delegate Ben Kline, would have barred jurisdictions from adopting policies or procedures restricting enforcement of federal immigration laws. While Kline claimed that the bill was merely designed to prevent localities from interfering with ICE investigations, Northam expressed concern that it would force local authorities to expend scarce resources on enforcing immigration laws.

- Washington Post article on Virginia bill