You are here

Open Wallet, Closed Doors: Exploring Japan’s Low Acceptance of Asylum Seekers

While Japan is one of the world's most generous contributors to humanitarian appeals, it approves very few asylum applications. (Photo: International Organization for Migration)

Even as forced displacement has reached an unprecedented scale globally, with war in Syria, violence and political instability in parts of Africa and the Middle East, and persecution in Asia and South America sending millions fleeing within and beyond their countries, Japan has remained largely untouched.

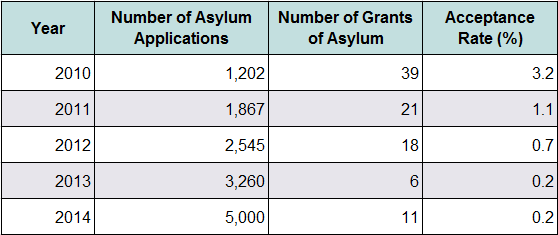

While Japan in 2014 witnessed a record number of asylum applications since its 1981 ratification of the 1951 Refugee Convention, the numbers remain small and the approval rate is extremely modest. Of the 5,000 individuals who filed for asylum in 2014, just 11 were granted refugee status—a 0.2 percent acceptance rate.

In total, Japan was home to nearly 12,500 refugees, asylum seekers, and stateless persons as of December 2014, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Asylum seekers with pending applications for refugee status comprised the vast majority.

While its acceptance of refugees and asylum seekers is very limited, Japan is one of the most generous countries in terms of financial contributions to support international humanitarian efforts. The world’s third largest economy, Japan in 2014 was the fourth largest donor to UNHCR, providing more than US $181 million. And Prime Minister Shinzo Abe pledged a further $1.6 billion at the UN General Assembly in September 2015 to fund new assistance for refugees and internally displaced persons in Syria and Iraq, as well as peace-building efforts in the Middle East and Africa.

Despite its financial generosity, Japan has gained a reputation as a closed country to refugees. Relatively few academic studies have examined the potential reasons behind Japan’s conservative attitude to granting asylum and hosting refugees. Drawing upon in-depth interviews with refugee experts including scholars, practitioners, and advocates in Japan conducted between June and September 2015, this article explores the reasons behind Japan’s low acceptance rate of asylum applications. Given the topic’s sensitivity in Japan, the names and organizational affiliations of the experts interviewed have been withheld. This article further examines both technical and institutional factors as well as government and public perceptions about asylum seekers and refugees that have potentially contributed to Japan’s stringent policy.

Barriers to Asylum

Japan’s reception of asylum seekers dates to the 1970s. Facing an influx of Indochinese refugees from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, Japan signed the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol in 1981 and 1982, respectively. In 1982, the government adopted the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act (ICRRA), which has been implemented by the Ministry of Justice’s Immigration Bureau. Since the end of the Indochinese refugee crisis, numbers of asylum applications have remained fairly low. Even as asylum claims have steadily increased since 2010, few cases have been approved (see Table 1).

Table 1. Asylum Applications and Accepted Cases in Japan, 2010-14

Source: Tabulations of data from the Immigration Bureau, Ministry of Justice.

While many refugee advocates say Japan’s recognition rate is extremely low, it is difficult to assess the level of acceptance as the Japanese government does not disclose all information to external parties regarding the determination process. Even UNHCR does not have full access to such information, as is normally granted to the agency in other industrialized countries with established refugee status determination systems.

This lack of transparency makes it difficult to evaluate Japan’s acceptance of asylum claims in 2014 from nationals from 73 countries (Nepal, Turkey, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar account for the largest numbers). Circumstantial evidence, however, indicates the Japanese government takes a stringent approach to asylum policy and implementation. Japan’s recognition rate stands out as tiny compared to other developed countries. The United States, for example, granted refugee status to 29.8 percent of cases in 2013 (25,199 approvals from 84,400 cases). In 2014, Germany gave refugee status to 21.7 percent of asylum seekers (37,640 of 173,070 cases), and the United Kingdom approved 37.2 percent (11,635 of 31,260 cases). During his 2014 visit to Japan, UN High Commissioner for Refugees António Guterres called on the government to review its asylum-recognition system, stating: “The numbers [of acceptance] are quite low. I think there is a reasonable presumption that the system is too rigid and too restrictive.”

There are several procedural, institutional, and societal obstacles that make seeking asylum in Japan particularly complex, and which potentially contribute to its low acceptance rate. The burden of proof falls heavily upon asylum seekers, who are responsible for providing tangible evidence to substantiate their asylum claim and prove to immigration officers the existence of persecution. According to an employee of a refugee-supporting organization in Japan, the documentation necessary to successfully substantiate a claim often amounts to several hundred pages, which also must be accurately translated into Japanese in order to be considered as evidence. Of course, those who flee in panic from violence or armed conflict are usually unable to carry or recover all the necessary legal or evidence documentation in advance of their flight.

Some experts interviewed said they suspected that the burden of proof placed on asylum seekers may be a result of the limited knowledge of government officials regarding current information on asylum seekers’ origin countries. The original information sources for these countries are almost always in English, and translating these documents into Japanese for official use takes substantial time. The limited access to updated material renders the asylum-information system outdated and results in more work for asylum applicants, who must fill in this knowledge gap by preparing additional evidence of persecution.

Furthermore, the Justice Ministry’s narrow interpretation of “persecution” presents a serious barrier to receiving refugee status. As stated in Article 1 of the 1951 Refugee Convention, people are considered refugees when unable to avail themselves of the protection of their country of nationality and unwilling to return to it owing to a “well-founded fear of persecution.” In Japan’s refugee status determination process, however, the phrase is interpreted as the “existence of an imminent threat to one’s life and body.” This restrictive interpretation removes from consideration those facing less immediate threats to their person or the possibility of future risks. While interpretation of the “well-founded fear” guideline generally encompasses an element of reasonable anticipation of future persecution, the Japanese requirement of an imminent threat refers strictly to a present risk, and is much more difficult to prove.

Implementation of the refugee status determination process is carried out solely by the Justice Ministry’s Immigration Bureau, presenting an institutional barrier to asylum, according to interviewees and the existing literature, as it functions essentially as an immigration-control body. With the mission of enforcing “proper immigration control,” the Bureau is responsible for preventing unauthorized migrants or “bogus” refugees from entering Japan through careful screening. On its website, the Immigration Bureau states its organizational mandates as follows:

By connecting Japan and the world through proper immigration control services under the motto "Internationalization in compliance with the rules," making efforts for smoother cross-border human mobility, and deporting undesirable aliens from Japan, the Immigration Bureau of the Ministry of Justice makes contributions to sound development of the Japanese society.

Experts on Japan’s asylum situation raised serious concerns that the immigration control mandate significantly affects the attitude of immigration officers towards asylum seekers. One academic long working on refugee issues in Japan commented:

In my view, many of [the] immigration officers have a bias that many asylum seekers are in fact economic migrants. They look through the asylum applications with such a view and try to detect these fake applicants as much as possible.

Other interviewees also pointed to a culture of denial among immigration officers, and highlighted that the refugee status determination system is in fact designed to reject as many applications as possible, not to save victims of human-rights abuse. As the Vienna Convention on treaties states, international agreements such as the 1951 Refugee Convention should be “interpreted in good faith,” in order to protect rights of refugees, for example. The current asylum system in Japan significantly compromises this principle.

Additionally, the system for appealing asylum rejections remains problematic. Appeals are heard by refugee examination counselors—Japanese professionals with backgrounds in humanitarian and refugee issues appointed by the Justice Ministry from a pool of experts recommended by external parties. The final decision resides with the Minister of Justice, who holds the power to overturn recommendations made by these professionals. Researchers and asylum experts have sharply criticized the concentration of power over refugee-status determination and appeals in a single governmental body. In fact, although rejected asylum seekers can resubmit their asylum application within seven days of receiving notice of rejection, experts interviewed said that there have been very few cases in which decisions were reversed on appeal.

Negative Perceptions toward Hosting Refugees

In addition to the procedural and institutional obstacles discussed above, societal perceptions of refugees may indirectly impact Japan’s asylum acceptance rate. First, there seems to be a widespread perception among the Japanese government and municipalities that refugees are an increasing burden on the host country and communities. Once granted refugee status, individuals are able to benefit from integration support provided by the Japanese government and civil-society organizations. However, some Japanese experts noted that even with access to integration assistance, the central government and municipalities do not believe refugees will be able to become economically self-sufficient. Because refugee status entails permanent residency, work authorization, and access to the same entitlement programs available to Japanese nationals, the Immigration Bureau is concerned that receiving cities and towns will be permanently responsible for taking care of refugees through public expenses.

Moreover, the vast majority of the Japanese general public lacks basic understanding about refugees. Refugee issues have been largely regarded as “something which takes place in far-away lands,” according to research conducted by the UNHCR Tokyo office. Consequently, most Japanese fail to distinguish refugees from economic migrants. One expert interviewee working for a refugee-supporting organization lamented:

Refugees are such a foreign concept for the Japanese public. Most people are mixing “refugees” with “immigrants” They don’t know why refugees left [their] country and seek asylum in Japan. In Japanese media, “economic refugees” is a frequently used term, which is evidence to show the lack of understanding of refugees in [the] general public.

The impact of this limited understanding on Japanese asylum policy remains debatable, however. Previous research points to a public perception that migrants, particularly those from other Asian countries, have contributed to the country’s rising crime rate and general deterioration of public security. Although unfounded—the number of crimes involving foreigners peaked in 2005—some experts interviewed said they think that a considerable number of Japanese are unaware of the official statistics and remain imbued with negative images towards migrants, including refugees. On the other hand, others commented there are a growing number of people who understand the need for humanitarian assistance and are more proactively engaged in attempting to host and support refugees in Japan.

More broadly, many observers have noted a deep cultural aversion to any form of immigration in Japan, despite an aging population and growing need for new workers. And while the foreign-born population in Japan has significantly increased in recent decades even without major changes to immigration policy, the concept of a homogenous culture and Japanese identity remains pervasive in popular discourse. It is possible this sentiment extends to all newcomers including refugees and asylum seekers. Prime Minister Abe reflected these attitudes in his address at the United Nations:

I would say that before accepting immigrants or refugees, we need to have more activities by women, elderly people and we must raise our birth rate. There are many things that we should do before accepting immigrants.

Furthermore, news coverage of a phenomenon deemed Gisou Nanmin, or fake refugees, might have shifted public perceptions in a negative direction. In early 2015, Japanese media sensationally reported that the country’s asylum application system had been abused by Nepalese brokers and bogus asylum seekers as a means of finding economic opportunities in Japan. Even though identified cases are relatively few, as reported by the media it appeared the entire asylum system was commonly manipulated by these “abusers,” generating grave concern among a number of experts interviewed for this article. The public buy-in and emphasis on Gisou Nanmin offers a possible justification for the Immigration Bureau to further tighten its screening of asylum applications. Alarmingly, with the increasingly restrictive attitudes toward asylum, genuine refugees might be labeled “bogus” and thus subject to immigration-control measures including deportation or detention.

Opening the Door

The multitude of procedural and institutional barriers to asylum and negative public perception have established a high hurdle to gaining refugee status in Japan. Several experts interviewed expressed concern that stringent policies have significantly compromised Japan’s humanitarian obligations.

Although Japan’s financial and material support has been widely recognized in the international community, some are urging the Japanese government to take further steps toward providing protection and making the asylum system “more in line with what are the best practices in international refugee status determination,” as UN High Commissioner for Refugees António Guterres said.

The world is experiencing one of the worst refugee crises and the UN regime has called for global solidarity in addressing the daunting magnitude of forced displacement. In the meantime, the Japanese government has thus far rejected almost all asylum applications by Syrians, granting refugee status to three out of more than 60 applications submitted as of mid-September 2015. The Justice Ministry provided 38 of the rejected Syrian applicants a temporary permit to stay in Japan on humanitarian grounds but this rare arrangement is only for one year and with no right to bring their family members to Japan. While Japan’s financial generosity was on display at the UN General Assembly, the government has not indicated any intention to accept more Syrian refugees.

If Japan intends to live up to its reputation as “a prestigious leader in humanitarian support,” according to UNHCR’s description, the government will need to strengthen its national asylum system and ensure that people in need of international protection have access to their rights, as enshrined in the 1951 Refugee Convention. Without reform, Japan will remain vulnerable to accusations that it fails to respect or uphold the obligations placed upon it as a signatory to international refugee and human-rights instruments.

Sources

Akashi, Junichi. 2014. New aspects of Japan’s immigration policies: Is population decline opening the doors? Contemporary Japan, 26 (2): 175-96.

Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network (APRRN). 2015. Japan’s review of their refugee status determination system raises new concerns. Rights in Exile Newsletter, July 1, 2015. Available Online.

Burgess, Chris. 2014. Japan’s ‘no immigration principle’ looking as solid as ever. The Japan Times, June 18, 2014. Available Online.

Dean, Meryll. 2006. Japan: Refugees and Asylum Seekers. United Kingdom: WRITENET Independent Analysis. Available Online.

The Economist. 2015. Japan’s asylum laws: No entry. The Economist, March 14, 2015. Available Online.

Eurostat. 2015. Asylum decisions in the EU: EU Member States granted protection to more than 185,000 asylum seekers in 2014. News release, May 12, 2015. Available Online.

Ito, Masami. 2014. Japan helps too few refugees: UNHCR Chief. The Japan Times, November 18, 2014. Available Online.

Kashiwazaki, Chikako and Tsuneo Akaha. 2006. Japanese Immigration Policy: Responding to Conflicting Pressures. Migration Information Source, November 1, 2006. Available Online.

Matthews, Chris. 2014. Can immigration save a struggling, disappearing Japan? Fortune, November 20, 2014. Available Online.

McCurry, Justin. 2015. Japan says it must look after its own before allowing in Syrian refugees. The Guardian, September 30, 2015. Available Online.

---. 2015. Japan takes no Syrian refugees yet despite giving $200m to help fight Isis. The Guardian, September 9, 2015. Available Online.

Ministry of Justice, Immigration Bureau. N.d. Wagakuni ni okeru nanmin higo no jōkyō-tō [Status of Refugee Asylum in Japan]. Accessed October 5, 2015. Available Online.

---. N.d. Nanmin nintei shinsei-sū no suii [Trends in Asylum Numbers]. Accessed October 5, 2015. Available Online.

Obi, Naoko. 2013. A Review of Assistance Programmes for Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Japan. Tokyo: UNHCR. Available Online.

Tarumoto, Hideki. 2004. Is state sovereignty declining? An exploration of asylum policy in Japan. International Journal on Multicultural Societies, 6 (2): 224-42.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2015. Asylum Trends 2014. Geneva: UNHCR. Available Online.

---. 2015. Japan. Accessed September 17, 2015. Available Online.

---. 2015. Points of Consideration Related to Global and Domestic Refugee and Statelessness Issues. Tokyo: UNHCR Representation in Japan. Available Online.

Yomiuri Shimbun. 2015. Gisou Nanmin: Fukusu brokers anyaku [Fake refugees: Multiple brokers engaged in nefarious plots]. Yomiuri Shimbun, February 11, 2015.

---. 2015. Gisou Nanmin: Tekihatsu no otoko 100 nin shinan [Fake refugees: Broker accused of instructing 100 Nepalese asylum seekers]. Yomiuri Shimbun, February 4, 2015.