You are here

Outsourcing Migration Management: The Role of the Western Balkans in the European Refugee Crisis

Asylum seekers board a train en route to Serbia from the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. (Photo: Mirjana Nedeva/UN Women Europe and Central Asia)

During the peak of the European migration and refugee crisis, hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers and migrants arrived in the European Union via the Western Balkans. In 2015, 600,000 registered at the Presevo camp alone, on the border of Serbia and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM). Key components of crisis management fell to non-EU states along the Western Balkans route, primarily Serbia and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, which paradoxically were not consulted on broader, European-wide responses.

The Western Balkans geographic region—comprised of Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia—is no stranger to refugee flows, having itself experienced massive displacement as a result of violence and ethnic cleansing during the 1990s. While Balkan countries at first opted to facilitate the movement of asylum seekers through their territories, to pass on responsibility for them, pressure from EU Member States ultimately led to a domino effect of border closures and increasing restrictions on movement as the crisis wore on.

As a series of cascading border restrictions in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Serbia, Croatia, and Slovenia closed the Western Balkans route, the number of people moving dropped dramatically. Migrants still wishing to travel north were pushed into more dangerous irregular channels in remote areas, and many became subject to police violence. Such practices are not unheard of within the European Union itself, but the trend carries worrisome implications for countries still consolidating democratically and developing the rule of law. Further, while many perceive the crisis in the Balkans to be over, thousands of migrants remain in limbo, stranded in countries along the route—nearly as many as in 2016. This article outlines the critical role played by countries along the Western Balkans route during the height of the crisis, charts the gradual closure of the route, and examines the political implications of migration for these countries and their EU accession aspirations.

The Western Balkans Route: Europe’s Back Door

The route north through the Western Balkans is not a new one, and has long been a pathway for those coming from the Middle East or Eastern Africa. Hundreds of thousands from within the Balkans also used this route to flee violence during the 1990s, when the region was primarily one of origin, not transit. In fact, an influx of Yugoslav refugees in the early part of the decade led to the development of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), which today finds itself under significant pressure. After the European Union opened up visa-free travel for Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, and Serbia in 2009-10, some from the region joined African and Middle Eastern flows seeking asylum further north.

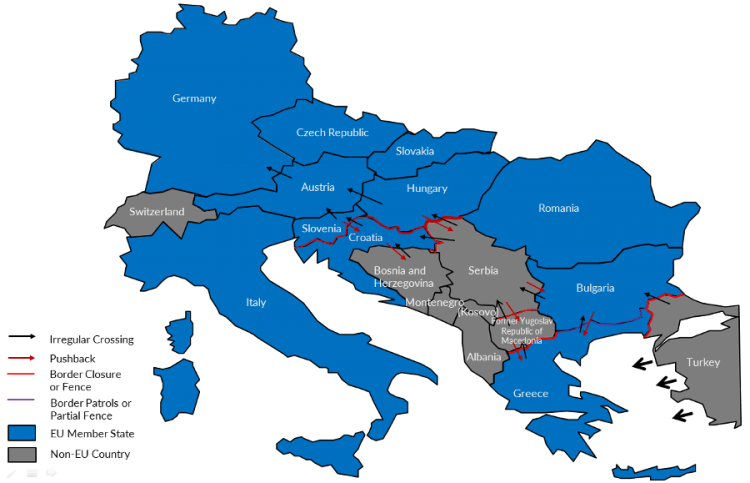

Figure 1. Main Irregular Migration Routes through Western Balkans, March 2016

Note: Border controls between Germany and Austria, and Austria and Slovenia, were introduced later, in 2017, and remain operational.

Sources: Route information from Senada Šelo Šabić and Sonja Borić, At the Gate of Europe: A Report on Refugees on the Western Balkan Route (Sarajevo: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Southeast Europe, 2016), available online. Map template from Presentation Magazine, “UK and Europe PowerPoint Maps,” available online.

In mid-2015, the number of irregular migrants passing through the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Serbia increased dramatically. Pressure on the two governments to address the flows grew, particularly amid reports of migrants suffering abuse at the hands of authorities and being struck by trains along railway lines. The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia responded by declaring a state of emergency at its borders. In November 2015, in an attempt to start managing and reducing flows, both governments enacted legislation allowing migrants to register “intent to seek asylum” upon entry and receive a 72-hour temporary permit to be in the country. This move created a fluid, hyper-temporary, semi-legal status that would become problematic later on.

Dominoes Begin to Fall

Following German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s “wir schaffen das” (“We can do it”) proclamation in August 2015 signaling asylum seekers would be welcomed in Germany, countries further south were more than happy to help migrants move along the route. Aided by international humanitarian organizations, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Serbia started facilitating transportation, sending migrants northward through their territories by train or bus. Particularly after Hungary erected border fences with Serbia and Croatia, countries focused on shuttling migrants northward into Croatia as quickly as possible to avoid responsibility for them. A Serbia-Croatia agreement organized six to seven trains daily, enough to transport 7,000 people.

Again and again the states along the Western Balkans route stressed that they were only transit countries, not ultimately responsible for migrants and asylum seekers. Leaders justified this stance by pointing to the migrants’ choice of destinations. The mayor of a Slovenian border town stated, “Here it is expected that we will provide for these people, in those hours they are with us, before they go to their final destination, which is not Slovenia [emphasis added].”

While facilitating transit, countries along the route introduced new national legislation and interpreted EU law in a manner that reduced the numbers traveling north. As candidates for EU membership (Slovenia and Croatia have been EU Member States since 2004 and 2013 respectively), these countries were also obliged to adopt EU-style asylum laws as part of accession negotiations. Because there were multiple routes north, if one country adopted restrictions others quickly followed suit to avoid responsibility for trapped migrants, resulting in a de facto coordination tacitly encouraged by EU Member States. In November 2015, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Serbia, and others enacted border controls to allow only migrants from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan to pass through, creating a hierarchy of “deservingness” based on nationality—which did not go unnoticed by migrants.

At the start of 2016, a number of EU Member States, often led by Austria and Germany, began imposing their own restrictions, unleashing a ripple effect of responses further south. Slovenia and Croatia adopted quotas to limit passage, aggravating the situation at the Greek-FYROM border. Meanwhile, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia had begun constructing a fence while periodically closing its border with Greece, going so far as to use tear gas to counter protests and barrages.

EU-Turkey Deal and the Closure of the Route

In April 2016, a deal between the European Union and Turkey took effect, seeking to curb migrant flows across the Aegean Sea by returning to Turkey those who had newly crossed into Greece. In exchange, the European Union agreed to give Turkey 6 billion euros and speed up visa liberalization for Turks. While the deal has been highly credited with stemming flows, the actions of countries along the Western Balkans route also played a significant and perhaps less-appreciated role. The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia responded to the deal by effectively closing its Greek border, again setting off a domino effect of restrictions. Any remaining migrants became trapped in the bottleneck, where they were ushered into reception camps.

Those who pressed on with their journey north now moved in clandestine fashion. Travel became more difficult, expensive, and dangerous due to strict police checkpoints and the threat of theft, assault, or kidnapping by gangs and smugglers. As the Balkan approach to migration turned hardline, police guarding borders into the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Hungary began using detention, violence (including use of dogs and beatings), or theft of migrants’ belongings to intimidate and deter people from attempting to cross. Further, those who successfully crossed could still be pushed back across the border, even if they applied for asylum, according to media and human-rights group reports. In February 2017, Hungary passed a law saying that pushbacks were legal within the entire country, not just in the border transit zones.

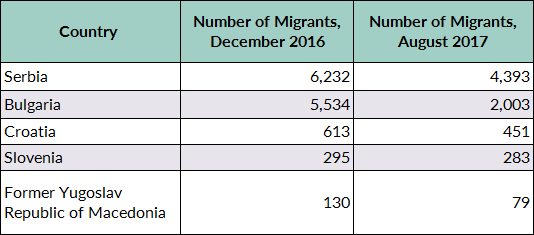

Table 1. Migrants Stranded along Western Balkans Route, December 2016 and August 2017

Source: International Organization for Migration, “Migration Flows – Europe,” updated August 9, 2017, available online.

Lives in Limbo

Rapid waves of border closures through the region have left thousands of migrants stranded in under-resourced camps and reception centers along the borders, primarily in Serbia and Bulgaria. Camps often have poor sanitation and hydration facilities, and in 2016 were ill-equipped to handle the particularly harsh winter, when nightly temperatures fell below 0° F on average. Many remain stuck in the region today, including a number living on city streets or in abandoned warehouses near train stations. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and charities are confined to providing aid to those living in state-controlled camps; as a result, far less help is available to the many resident outside the camps. In some cases unrest has broken out between migrants and locals, including summer-long protests in Serbia and Bulgaria and clashes with police, causing delays in registration and departure.

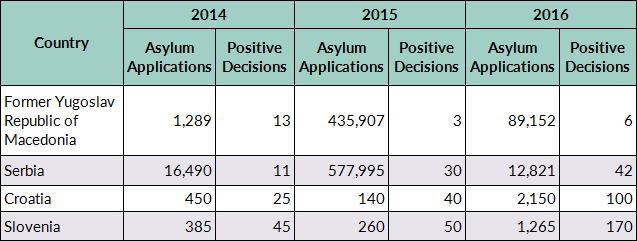

Despite a dramatic surge in asylum applications in the region in 2015, the majority of applications during the crisis were withdrawn or otherwise closed. This indicates that asylum seekers registered intent to apply and filed an application, but then presumably left the country before the case was processed, or intentionally abandoned it to pursue one elsewhere. Tiny numbers of asylum claims were approved in each country (see Table 2).

Table 2. Asylum Applications and Positive Decisions by Country, 2014-16

Note: Macedonia and Serbia require migrants to register “intent to seek asylum” in order to pass through their territory; nearly all moved on and abandoned these claims.

Source: Bodo Weber, The EU-Turkey Refugee Deal and the Not Quite Closed Balkan Route (Sarajevo: Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung in Southeast Europe, 2017), available online.

Further, legal routes for asylum in these countries can work against applicants. Migrants who attempt to leave are seen as abusing the asylum system, and become ineligible to apply for asylum there. Under safe third-country rules, travel along legal routes sometimes results in forced return or pushback to the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Greece, or Turkey. Meanwhile, assessments by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) point to gaps in implementation of asylum policy in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Serbia.

Even those few who are granted asylum in the Balkans face a difficult road ahead. These states lack the integration programs and financial benefits more common in Western Europe. In addition, the European Court of Justice in July 2017 ruled the Dublin Regulation could be applied to arrivals during the migration crisis, meaning those who made it to any EU Member State other than Germany can be sent back to their point of entry into the European Union, in most cases Croatia, which could further challenge limited processing capacity in the region.

Implications for a Fragile Region

While most of the migrants have moved on from the region, the impacts of the crisis on the Western Balkans are still felt today. The movement of hundreds of thousands of people has renewed dormant tensions between and within individual Balkan countries, while exacerbating strains between the Balkans as a region and the European Union. Responses to the crisis also hold important lessons for the still-uneven development of democratic institutions in the region, as well as for migration management in Europe more broadly.

Current economic growth is not enough to guarantee ample jobs in the region, and the transition to modern market economies remains incomplete. While regional unemployment has declined since 2010, it remains at 21 percent, with inactivity particularly high among women, the less educated, and youth. Combined with always-simmering ethnic tensions, these trends provide fertile ground for populism.

The hope of EU accession, following the example of other post-communist countries, was a powerful beacon and motivator of initial democratic reform in the Balkans. The European Union has long played an important carrot-and-stick role through conditionality policies promoting democratization in the region. Running interference for the European Union on migration management may give these countries additional leverage in negotiations.

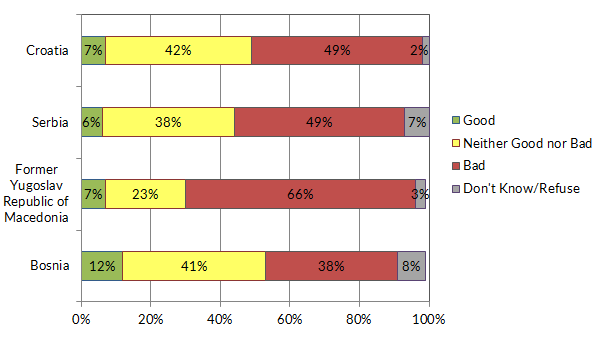

For Serbia, the crisis happened alongside the opening of its first EU accession chapters, perhaps a contributing factor in its willingness to register asylum seekers (though always predicated on the assumption they would soon leave). Yet as borders started closing and the temporary nature of the migrants’ presence ended, public opinion in Serbia and its neighbors grew more negative. Asylum seekers and migrants were increasingly seen as a security threat and financial burden on already strained economies, despite the fact that most of the transportation and reception costs were covered by NGOs or the European Union. Expressing a view common in the region, Serbian Prime Minister Aleksandar Vučić stated: “Serbia must not become a parking lot for Afghans and Pakistanis whom no one else in Europe wants.”

Migration has complicated the precarious political and economic situation in individual Balkan countries. Although Serbia has extended labor market access to migrants, the lack of host-country language skills and difficulty getting academic and professional credentials recognized present high barriers to finding suitable employment. Balancing the integration of the newcomers who remain with the need to improve job prospects for disaffected local youth will be difficult and could cause tensions. In addition, the profits derived from migrant smuggling have brought old drug-smuggling networks back to life, which threaten to hamper the region’s democratization and rule of law development.

In the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, an unrelated political crisis related to corruption scandals meant that the migration flows did not receive as much media attention as in other places. And if anything, the government’s ability to close the border and act on internationally brokered agreements shored up its legitimacy against the opposition party.

Figure 2. Responses to the Question “What Do You Think about Refugees Coming to Live and Work in Your City? Is It Good or Bad for Your Economy?” by Nationality, 2016

Source: Regional Cooperation Council (RCC), Balkan Barometer 2016: Public Opinion Survey (Sarajevo: RCC, 2016), available online.

Pressures on state capacity to host the new arrivals have also reopened fissures between Balkan countries. Croatia’s imposition of border restrictions sparked a trade war with Serbia, representing the most significant dispute between the two countries since former Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević was deposed in 2000. In a sign of the suspicion and animosity, Croatian Prime Minister Zoran Milanovic said: “Until I see the Budapest–Belgrade axis stop burdening Croatia with refugees, I will remain convinced that [Serbia is] doing something behind our back.”

In Search of Stability

After years of political and economic crises, the European Union appears to place high priority on maintaining stable governance and establishing control over migration. The European Commission has responded cautiously to Poland’s refusal to participate in the refugee quota system, though it has reacted more harshly to revisions to its judicial system. Further, EU leaders reacted positively to Vučić’s clear and convincing victory in the Serbian elections in April 2017, despite accusations by the opposition of his involvement in stifling free press and civil society. Meanwhile, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina are flirting with illiberalism, and renewed ethnic tensions in the latter could embolden minorities in neighboring countries. A February 2017 poll showed that 38 percent of Serbians report fearing war will break out in the Balkans in the next five years. The actual likelihood of this aside, any renewed conflict would create an entirely different migration crisis for the European Union—one it undoubtedly would prefer to avoid.

During the height of the migration crisis, border closures and other hardline policies in the region were either ignored by the European Union or praised by Member States—some of which, such as Bulgaria and Hungary, employed these practices themselves. Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and Austrian Foreign Minister Sebastian Kurz both visited the region and thanked the Balkan governments for their role in managing the crisis. The irony of this is not lost on Serbians: They are tasked with guarding the Schengen free movement zone without being a part of it, much less the European Union, which has relied on external actors for migration management amid its inability to rally all EU Member States to agree upon burden-sharing and necessary reforms to the CEAS and other policies. As a result, EU handling of the crisis has only fueled euroskeptic debate and criticism in the Balkans.

With many EU Member States souring on the idea of expansion and EU credibility waning in the wake of the migration and eurozone crises, Brexit, and rising populism, Balkan leaders may grow less likely to view the European Union as a club they want to join. Seeking to capitalize on this, actors including China, Russia, and Turkey have expanded their influence in the region. Russia has the most overt influence, especially in Serbia, Bosnia, and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, which rely on it for oil and gas. Serbia’s military conducted more than ten times as many exercises with Russian troops than with Western forces in 2016. No stranger to playing the spoiler, Russia could easily encourage nationalist groups and feed euroskepticism with its anti-West narrative, while serving as an example for how to stay in power amid weak economic results.

The Price of Migration Management

Though migration flows through the Western Balkans were largely transitory, they have illuminated cracks in the European system of border management and may have lasting effects on the region. The lesson from the Balkan experience is that in the absence of common policy to deal with an influx of asylum seekers, countries may compete to be the lowest common denominator, with no one wanting to be saddled with ultimate responsibility. This knowledge could inform future proactive policy development ahead of the next crisis.

Balkans countries pulled into a broader border management role may try to cash in by pushing for EU accession: In fact, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia has already lobbied EU leaders to set a date to open membership negotiations. However, for Balkan autocrats who have given up on EU accession, the powerful example of Turkey, where President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has cracked down on democratic principles while retaining leverage with the European Union, may represent an attractive alternative.

Ultimately, the worry is that these countries will become further entrenched “stabilocracies” under a façade of democracy. After consolidating power through cronyism, nationalism, and a touch of socialist nostalgia, these leaders may eventually be able to skirt independent scrutiny and judicial review. It remains to be seen what effects the EU quest for migration management, which has led to approval of a much-criticized EU-Turkey deal and the tacit approval of Balkan leaders’ slide toward authoritarian rule, will ultimately have on the shaky democratic institutions of its partners.

Sources

ACAPS. 2017. Serbia: Winterisation for Refugees. Short note, ACAPS, January 14, 2017. Available online.

ACAPS and Start Network. 2015. Briefing Note Update: The Balkans – Asylum Seekers, Migrants, and Refugees in Transit. Briefing note, ACAPS and Start Network, November 17, 2015. Available online.

Austin, Robert. 2017. The Balkans: Bad News Rising. Commentary, European Council on Foreign Relations, March 24, 2017. Available online.

BMI Research. 2017. Balkans’ Rising Instability to Exacerbate European Security Concerns. Country Risk Report, February 1, 2017. Available online.

De Borja Lasheras, Francisco. 2016. Return to Instability: How Migration and Great Power Politics Threaten the Western Balkans. London: European Council on Foreign Relations. Available online.

Denti, Davide. 2015. Serbia, the Unexpected Friend of Syrian Refugees. Boulevard Extérieur, September 3, 2015. Available online.

Dernbach, Andrea. 2017. “Die Balkanroute ist nicht dicht.” Der Tagesspiegel, March 11, 2017. Available online.

European Western Balkans (EWB). 2017. Balkan Migration Route: Ongoing Story. News release, February 22, 2017. Available online.

European Commission. 2016. Implementing the European Agenda on Migration: Commission Reports on Progress in Greece, Italy, and the Western Balkans. Press release, February 10, 2016. Available online.

Eurostat. 2017. Asylum and First Time Asylum Applicants by Citizenship, Age, and Sex: Annual Aggregated Data. Updated July 21, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. Final Decisions on Applications by Citizenship, Age, and Sex: Annual Data (rounded). Updated July 7, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. Asylum Applications Withdrawn by Citizenship, Age, and Sex: Annual Aggregated Data. Updated July 17, 2017. Available online.

Frontex. 2017. Risk Analysis for 2017. Warsaw: Frontex. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2017. Migration Flows - Europe. Updated August 9, 2017. Available online.

Katsiaficas, Caitlin and Ariel G. Ruiz Soto. 2016. Top 10 of 2016 – Issue #7: Migrants and Smugglers Get Creative to Circumvent Immigration Enforcement. Migration Information Source, December 8, 2016. Available online.

Kilibarda, Pavle and Nikola Kovačević. 2017. Country Report: Serbia. Belgrade: Belgrade Centre for Human Rights and AIDA. Available online.

Mandić, Danilo. 2017. Anatomy of a Refugee Wave: Forced Migration on the Balkan Route as Two Processes. Europe Now Journal, January 5, 2017. Available online.

Moving Europe. 2016. On the Situation of Migrants in Serbia in Autumn 2016. Moving Europe, November 9, 2016. Available online.

---. 2016. Report on Push-Backs and Police Violence at the Serbo-Croatian Border. Moving Europe, February 2, 2016. Available online.

Nallu, Preethi. 2017. Europe’s Outsourced Refugees. Refugees Deeply, March 2017. Available online.

Pantovic, Millivoje et al. 2016. Balkan War Crime Suspects Maintain Political Influence. Balkan Insight, December 7, 2016. Available online.

Regional Cooperation Council (RCC). 2016. Balkan Barometer 2016: Public Opinion Survey. Sarajevo: RCC. Available online.

Sardelić, Juija. 2017. From Temporary Protection to Transit Migration: Responses to Refugee Crises along the Western Balkans Route. EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2017/35, European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, July 2017.

Šelo Šabić, Senada and Sonja Borić. 2016. At the Gate of Europe: A Report on Refugees on the Western Balkan Route. Sarajevo: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Southeast Europe. Available online.

Teffer, Peter. 2015. Balkan Countries Close Borders to ‘Economic Migrants’. EU Observer, November 20, 2015. Available online.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). N.d. Population Statistics, Asylum-Seekers (Refugee Status Determination). Accessed July 14, 2017. Available online.

UNHCR and IOM. 2013. Refugee Protection and International Migration in the Western Balkans: Suggestions for a Comprehensive Regional Approach. Geneva: UNHCR and IOM. Available online.

Vasovic, Aleksandar and Ivana Sekularac. 2015. Serbia Bans Croatian Goods as Ties Hit Low Over Migrants. Reuters, September 23, 2015. Available online.

Weber, Bodo. 2017. The EU-Turkey Refugee Deal and the Not Quite Closed Balkan Route. Sarajevo: Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung Southeast Europe. Available online.

World Bank Group and Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies. 2017. Western Balkans: Labor Market Trends 2017. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online.