You are here

Overwhelmed by Refugee Flows, Scandinavia Tempers its Warm Welcome

Volunteers assist asylum seekers at a train station in Malmö, Sweden. (Photo: Johan Wessman/News Øresund)

Despite being geographically, culturally, and climatically more distant from the Middle East than the rest of Europe, Sweden took in more asylum seekers per capita than any other European Union Member State in 2015. And its neighbors Norway and Finland also saw major inflows of asylum seekers, bringing to Scandinavia vivid proof of the war and instability plaguing Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, as well as the repression and lack of economic opportunity marking parts of Africa.

More than 1 million asylum seekers and migrants reached the European Union by sea and land in 2015, in chaotic, unauthorized flows that taxed rescue and care operations, left policymakers with policy proposals inadequate to the enormity of the challenge, and hit some countries much harder than others. As hundreds of thousands of migrants and asylum seekers flowed through Greece and the western Balkans, many kept their eye firmly on reaching Germany or heading further to wealthy Scandinavia—bypassing destinations such as France or the Netherlands in favor of Sweden, Finland, and Norway.

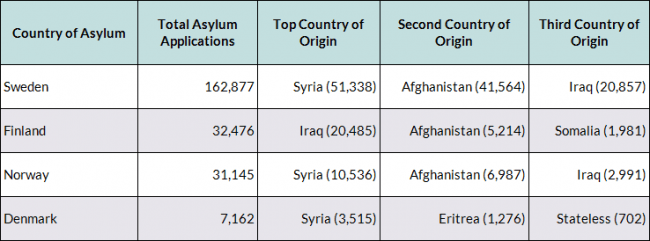

Sweden received more than 160,000 asylum applications in 2015, and was second only to Germany in absolute numbers, though first in numbers of arriving Syrians (see Table 1). Finland received more than 32,000 asylum applications, and ranked third in the European Union for Iraqi arrivals on the year. In October, at the peak of inflows, Finland was first in the European Union in total Iraqi arrivals. Norway and Finland ranked fourth and fifth in asylum receipts per capita in 2015.

In Norway (which is not an EU Member State but has signed on to the EU Dublin Regulation governing asylum), more than 31,000 asylum applications were lodged in 2015, and the country is bracing for as many as 60,000 new applicants this year. Meanwhile, Denmark, with its more restrictive immigration policies, proved less popular, receiving about 7,100 asylum applications in the first three quarters of 2015. Yet Denmark still managed to rank ninth per capita in asylum receipts for 2015.

Prior to this crisis, Scandinavian countries had some of the most generous refugee and asylum policies in Europe. Sweden, for example, began offering immediate permanent residence to all successful Syrian asylum applicants in 2013, while Finland provided some of the largest stipends to asylum seekers awaiting the outcome of their claims. Both still offer extensive integration programs for successful applicants.

As the continuing arrivals overwhelmed the asylum systems in these rich but small countries and once largely welcoming publics began to chafe at the growing burdens, policymakers began to recalibrate their policies.

The Nordic governments are aiming to reduce their desirability as destinations by tightening asylum benefits to the minimum standards. Sweden rolled back its permanent residence policy for all newly arriving Syrians, and has proposed granting only temporary status to successful asylum seekers of all nationalities, including Syrians. Sweden’s Interior Minister indicated 60,000 to 80,000 asylum applications likely will be rejected in 2016 based on past denial rates, and has asked several agencies to propose plans for increased deportations. Finland is also considering ways of swift and effective return for failed asylum seekers. Norway, meanwhile, has passed legislation making it easier to deport asylum seekers and migrants without valid claims, and Denmark has approved a controversial policy allowing authorities to confiscate valuables from new arrivals to help defray the costs of their accommodation.

This article examines how the migration and refugee crisis has affected Scandinavia, the role of the diaspora and social media in promoting the region as a desired destination, and changing attitudes among policymakers, publics, and asylum seekers.

Destination North: Why Scandinavia?

Beyond the headline-grabbing violence of ISIS and continued conflict in countries such as Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan, many migrants and asylum seekers have been driven to seek a better life in Scandinavia by a number of other, less dramatic factors that were present before but have intensified in recent years. Violence and oppressive regimes exacerbate systemic discrimination and repression of religious and ethnic minorities, resulting in grave societal inequalities. Closely linked to a vicious cycle of societal discrimination, poverty, and unemployment, the deterioration of social infrastructures has led to decreased public services and social mobility, while unsatisfactory economic environments for business and entrepreneurship hamper development and prompt migration. Furthermore, high population growth rates across the Middle East have accelerated the weakening of social supports, placing a heavy burden on government services such as education and health care in each country, while economic growth has not kept pace with the number of workers entering the labor market each year. Within this context and in the face of extreme violence and civil war, many have sought refuge, safer and better living conditions, or economic opportunities and greener pastures abroad.

But why did Sweden, Finland, and Norway—with vastly different climates, both physically and mentally—become such significant destinations?

Table 1. Asylum Applications Filed in Scandinavian Countries by Top Countries of Origin, 2015

Note: Figures for Denmark include the first three quarters of 2015.

Sources: Finnish Immigration Service, “Asylum applicants 1/1-11/30/2015,” available online; Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (UDI), “UDI-direktøren oppsummerte asylåret 2015 (med video),” [UDI director summed asylum year 2015 (with video)] (press release, January 7, 2016), available online; Statistics Denmark, “Asylum applications and residence permits,” accessed February 2, 2016, available online; Swedish Migration Agency, “Applications for asylum received, 2015,” available online.

The Tradition of Generous Asylum Policies

Well known for having some of the world’s highest living standards and respect for the rule of law and equality, Scandinavian countries have long prided themselves on playing responsible, constructive roles on the world stage. Sweden, a champion of high global morals, has been historically refugee-friendly, receiving resettled refugees through the United Nations since 1950. Finland adopted a legalistic approach to immigration and humanitarian issues, with a focus particularly on peace keeping and conflict resolution abroad. Norway has long considered itself the global peace facilitator, whereas Denmark elaborated policies to enhance the well-being of its resident population, including newcomers. With this approach to humanitarian affairs, Scandinavia has been largely welcoming to refugees and asylum seekers from diverse origins. All four countries have long traditions of participation in refugee resettlement from countries of first asylum and have developed comprehensive humanitarian protection policies.

The result has been that Scandinavian countries had some of the most generous refugee and asylum policies in Europe—until 2015, when their governments began adopting stricter legislation and policy reforms to narrow benefits (discussed in more detail below).

Scandinavia’s welcoming reputation thus acted as a major pull factor, contributing to the decisions of many asylum seekers to lodge their claims in Nordic countries rather than elsewhere in Europe.

Examples of the now changing, but in some ways still expansive policies (cash benefits offered in Sweden and Finland, for example, although decreased remain higher than in other European countries) are many. In Sweden, all asylum seekers who are granted full refugee status receive permanent residence permits, while those granted a subsidiary protection status receive temporary residence. In 2013, Swedish migration authorities decreed that all Syrians granted any form of protection would receive permanent residence. Previously, only about half were given permanent status, the remainder getting three-year permits. Asylum seekers are guaranteed accommodation if they need it, though due to shelter limitations, alternative locations including schools, sports halls, and even a theme park are being utilized. Asylum seekers have access to free health services, and those in need of financial benefits receive deposits in a bank account directly after lodging their claim. Cash stipends are distributed for food (if not already provided in accommodation) and basic necessities. If their claims are recognized, refugees and protection beneficiaries are entitled to participate in a two-year integration program that offers language classes, help finding a job, and a monthly stipend.

In Finland, a supplementary reception allowance depends on applicants’ special needs, such as health care or transportation. Cash allowances are provided throughout each phase of the asylum procedure. In addition to free accommodation and health and social services, asylum seekers who need to buy food receive monthly cash grants. Asylum seekers also have the right to work three months after submitting their applications. If approved, refugees receive state-financed housing for three years, welfare, education, and child benefits, language classes, and help finding a job.

Asylum seekers in Norway are entitled to live in reception centers where they receive stipends for basic necessities and can apply for further financial assistance. They have access to health care, can apply for a work permit, and their children have the right to go to school. Those granted refugee protection are given a renewable residence permit, typically valid for three years. Those granted subsidiary protection are also given a residence permit, but of a more limited duration.

In Denmark, most asylum seekers are required to live in asylum centers while their applications are being processed. The Immigration Service provides cash allowances for clothes and personal hygiene, necessary health care and social services, and child education. Asylum seekers who meet certain conditions can work while waiting for a decision on their claim.

A lengthy asylum procedure is another important pull factor. Swedish authorities have often considered the total period of stay (from arrival to return), rather than the processing time of applications, to be of influence as a factor attracting asylum applicants from the Middle East and North Africa. A lengthy procedure may be particularly appealing to migrants due to the cash and other benefits received during the period in which applications are being processed.

Diaspora Presence and Social Media

With decades of refugee resettlement from diverse countries, significant diaspora communities have grown in Scandinavia, including Syrians in Sweden and Kurds from northern Iraq in Finland. The presence of these diaspora groups may have contributed to increased flows of their countrymen and women to Scandinavia in recent years. As new arrivals become more established in the host country, they share word with their families and networks, and a destination or route that may not have been widely accessed suddenly receives much greater interest. Social media and migrant networks played an important role in disseminating the desirability of Scandinavia as an asylum destination. Many of those contemplating the journey to Europe use social media platforms to gain information on routes and reception policies, and in some cases, access to smugglers offering to facilitate their movement.

Globalization and the expansion of modern communication technology have allowed for much closer networking and rapid information sharing—even among people who have only just arrived at destination. Therefore the presence in Scandinavia of newly arrived individuals has been enough to trigger communication and create further information channels with communities of shared origin.

As is the case with much information passed by migrants, however, some of it can be erroneous. As members of the established Syrian and Iraqi diaspora and early arrivals shared their positive experiences and details of Scandinavia’s generous policies on social media, the information at times became distorted or manipulated to present Finland and Sweden as “Eldorados,” where anyone could pursue a fine life, work, a good salary, and a house.

Prospective migrants were told that anyone expressing the word “asylum” would get it, with no questions asked. The asylum process, however, is not that simple, and asylum seekers face many challenges in first getting approved, then in integrating into Nordic societies. As increasing numbers arrived and governments struggled to accommodate them, conditions worsened, with many asylum seekers confined to reception centers in remote towns and temporary tents in the midst of cold winter. Locals in these small towns were more often than not ill at ease with the suddenly established reception centers and the presence of hundreds of mostly young Middle Eastern men. And the drastic cultural differences, reduced service provision due to capacity shortages, and long wait times for asylum decisions created a sense of uncertainty and resentment among some of the refugees.

It is possible there was little direct contact between the established Iraqi and Syrian diasporas and the newcomers to indicate these changes or relay accurate information on reception conditions. Without knowing the huge numbers of their countrymen who would ultimately seek asylum, diaspora members were perhaps overconfident about the probability of the Nordic countries to accept the asylum seekers. Or newcomers may have been overconfident about their ability to stay, even with warnings from their countrymen already on site. This possible overconfidence was likely due to the loud and appealing misinformation propagated on social media long before the decision was made to set off on the journey.

Facilitated Routes and New Sources of Syrians and Afghans

Smugglers in the countries of origin and along the way exploited the emerging interest in Scandinavia, facilitating access to the region through new routes. In addition to the Balkan route by land, and the risky boat routes across the Aegean and Mediterranean seas, Russia has become an important origin and transit country. There is a large migration potential of Syrians and Afghans already present in Russia, with about 12,000 Syrians (mainly workers, about one-third of whom have received a legal protection status) and estimates of 150,000 Afghans (most of whom arrived as refugees in the 1990s, now mostly without work) in the country. Russia’s declining economy has strained living standards for immigrant workers, while few refugees have received protection status through the corrupt and inefficient asylum system.

Smugglers have facilitated the movement of Syrian, Afghan, and other Middle Eastern migrants to border crossings with Finland and Norway north of the Arctic Circle. Because Russia does not allow border crossings by foot in those locations, and Norwegian and Finnish antitrafficking laws prevent asylum seekers from being driven across, smugglers provided bikes, often sold at inflated prices and not fully functional, for migrants to make the crossing. In December, Finland closed the Lapland border to bicycle entries, citing the dangers of such travel in winter conditions. And in January, Norway attempted to deport approximately 5,500 Middle Eastern asylum seekers to Russia, at first threatening to send them by bicycle in the manner they arrived. Russia has refused to re-accept most of the migrants, and the three countries continue to dispute who is responsible for accommodating them and processing their asylum claims.

Changing Attitudes and Stricter Policies

Public Opinion and Rise of the Far Right

Despite the initially welcoming climate among the public for those in need and fleeing danger, a fundamental change in public attitudes is taking place in Scandinavia from historically welcoming—or at least neutral—to increasingly hostile, as reflected in rise of populist parties including the Sweden Democrats, Finns Party, Danish People’s Party, and Norway’s Progress Party. From the fringe of Scandinavian politics, these parties have grown over the last decade, gaining substantial public support. The Sweden Democrats continue to steadily rise in the polls, reaching a record 19.9 percent support in polling conducted by the country’s statistics agency in November. The Finns Party won 17.7 percent of the Finnish vote in 2015 elections and joined the government coalition as the second-largest party in Parliament. Though the Finns Party has dropped in the polls (to 9.6 percent in January 2016) and softened its stance within the coalition, the anti-immigrant rhetoric and sentiment of some of its members of Parliament has now spread to members of other parties in Finland.

In elections in June 2015, the anti-immigration Danish People’s Party came in second, with 21 percent of the vote. The party’s stringent policies on immigrants and refugees have also spread throughout Danish politics as the ruling right-wing Venstre Party has taken a hardline stance on accepting new inflows of asylum seekers and acted on campaign promises to tighten asylum regulations. In December, Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen suggested the 1951 Geneva Convention on Refugees might need to be revised.

Beyond politics, Sweden, Finland, and Norway have also witnessed some physical attacks against asylum seekers, including suspected arson attacks on reception centers. In Sweden, at least a dozen buildings marked for asylum accommodation have been set on fire since summer 2015.

Reasons for this crucial shift towards a more negative climate on immigration are many. The rise of social media has offered an anonymous platform to express previously unpopular or politically incorrect ideas. Amid this diversified expression of public opinion, latent, more extreme ideas have seen daylight and gained popularity.

These often xenophobic and nationalist sentiments have been fueled in part by economic downturns experienced over the last decade, and by a rise in immigration—both of migrant workers from the European Union and new refugees from farther abroad. Asylum seekers and refugees with their well-publicized benefits and poor levels of integration have often become the scapegoat for many domestic social ills.

The extensive asylum immigration experienced in 2015 sparked further xenophobia and anti-immigrant sentiment. The influx of largely young men from different cultures and religions, and the costs associated with their accommodation, sparked protests and in some cases physical attacks. Hence, in reaction to voters’ sharpening tones, politicians are making asylum legislation more restrictive across Scandinavia.

However, it would be incorrect to say that such skepticism is based solely on latent xenophobia rising to the surface. It is also a question of the ability and agility of these rich—although very small countries of a few million citizens each—to carry the burden and costs of integrating tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of would-be Swedes and Finns.

Tighter Policies, Smaller Stipends, and Swifter Returns

As migration continued unabated into November and December 2015, Scandinavian governments began to tighten their asylum and border policies in an effort to reduce their appeal as destinations. In Sweden, the government proposed offering recognized refugees three-year temporary residence instead of permanent status, while those granted subsidiary protection would get one-year temporary residence. If the Swedish Parliament approves the proposal, it will go into effect in April 2016 and remain in force for three years. In addition, Sweden proposed restricting access to family reunification to immediate family members of recognized refugees. Refugees must also apply to bring family members within a much tighter timeframe. The government “wants to temporarily adjust the asylum regulations to the minimum level in the EU so that more people choose to seek asylum in other EU countries,” according to a press release on the new measures. Sweden also reintroduced border controls with Denmark, starting a domino effect as Denmark then reinstated controls on its border with Germany.

As the new Danish government took office in June, it slashed cash benefits available to asylum seekers by 45 percent. Further, over the summer Denmark launched an ad campaign in Lebanon telling potential asylum seekers not to come as benefits were being reduced and that rejected applicants would be swiftly returned. And in January 2016, the government passed controversial legislation allowing authorities to confiscate migrants’ valuables to offset their accommodation costs.

Finnish President Sauli Niinistö, whose position is largely that of opinion leader rather than executive, pondered in a February 2016 address to Parliament whether the 1951 Geneva Refugee Convention is outdated. According to Niinistö, there needs to be a more effective legal tool to rapidly sort out the needy and persecuted from those misusing the asylum system for economic purposes. Finland has sought to establish new bilateral agreements with origin countries on returns, as well as to find ways to better facilitate returns. Finland is also implementing a new law denying rejected asylum seekers eligibility for any kind of residence permit or reception benefits. To address the unprecedented number of asylum seekers and enforce the new regulations, Finnish authorities have recruited hundreds of new officials.

And in Norway, which also introduced border controls with Sweden, newly appointed Immigration Minister Sylvie Listhaug in December unveiled a draft bill with a series of stricter asylum regulations that will be voted on later in February. The measures include allowing family reunification only after the applicant has worked or gone to school in Norway for four years, issuing vouchers instead of cash for basic needs to prevent money being sent out of the country, and requiring older asylum seekers (ages 55 to 67) to learn the Norwegian language and social customs. The bill also denies asylum to migrants who arrived on transit visas from Russia and to applicants who fail to present valid ID. Further, those who are granted temporary residence status will not automatically be put on a path to permanent residence.

“Unrealistic Perceptions” and Voluntary Return

With the tightening of policies, increasingly negative public opinion, and worsening reception conditions due to capacity shortages, significant numbers of asylum seekers have chosen to withdraw their applications and leave Scandinavia or take advantage of assisted voluntary return programs.

In Norway, 805 of the 31,145 individuals who filed for asylum in 2015 chose to withdraw their claims, according to the Directorate of Immigration (UDI). Though the agency does not interview those who withdraw to determine why, Katinka Hartmann, head of UDI’s returns unit, said “we assume many of them had an unrealistic and erroneous perception of the types of opportunities they would have in Norway.” It is likely, however, that many of those from war-torn countries such as Syria do not return home, but go instead to a third country.

Iraqi migrants in particular have reversed course, as “there are thousands of Iraqis who have come back and thousands more that want to,” according to Sattar Norwuz, a spokesman for the Iraqi Ministry of Displacement and Migration. Norwuz pointed to the influence of television coverage of the migrant flows, suggesting they encouraged other young Iraqis to try their luck in Europe. In 2015, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) assisted more than 3,000 Iraqis to return to Iraq from 14 different European countries, including significant numbers from Finland.

Future Migration Deterred or Rerouted?

The numbers of asylum seekers from the Middle East and Afghanistan to Scandinavia appear to have slowed in January 2016—though whether a brief winter season pause or a fundamental realignment remains to be seen. The current tendency to deploy passport controls and to limit application of the 1951 Refugee Convention to the minimum standards, combined with strong measures to encourage voluntary repatriation and decrease cash assistance, may prevent as large an inflow of asylum seekers in 2016. However, the foundations for significant future migration remain: The civil war rages on in Syria, while conflict in Afghanistan and Iraq continues and intensifies. In the Middle East, few efforts to halt population growth have been initiated, while efforts to establish or expand economic infrastructures and to manage youth unemployment have proven largely ineffective in the face of such turmoil. As there is now both an established and a very recent diaspora of Syrians, Iraqis, and Afghans in Scandinavia, it remains to be seen whether and how the Russian source and transit route will evolve. Many migrant workers and former refugees already present in Russia, and those who would avoid the risky journey to Europe by boat, may look to the experiences of their countrymen across the Arctic border and see better economic opportunities despite the border closures. Such flows have added—and may continue to do so—a layer of complexity to Scandinavian politics, public atmosphere, and government reactions.

Sources

Brabant, Malcolm. 2015. New Danish law to discourage refugees. Deutsche Welle, August 31, 2015. Available Online.

Danish Immigration Service. 2015. Asylum. Last updated October 16, 2015. Available Online.

Deutsche Welle. 2015. Norway’s Listhaug unveils tighter asylum rules. Deutsche Welle, December 29, 2015. Available Online.

European Asylum Support Office (EASO). 2015. Latest Asylum Trends – November. Malta: EASO. Available Online.

Finnish Immigration Service. 2016. Asylum applicants 1/1-11/30/2015. Available Online.

---. 2016. International Protection and Asylum in Finland. Accessed February 2, 2016. Available Online.

Government of Sweden. 2015. Government proposes measures to create respite for Swedish refugee reception. Press release, November 24, 2015. Available Online.

Henley, Jon. 2016. Danish PM counts on popular support in tackling refugees. The Guardian, January 18, 2016. Available Online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2016. IOM Helps Iraqi Migrants Voluntarily Return Home from Belgium. Press release, February 2, 2016. Available Online.

Local Denmark, The. 2015. Denmark to reduce asylum benefits. The Local Denmark, July 1, 2015. Available Online.

Local Norway, The. 2016. Asylum seekers leave Norway over ‘unrealistic perceptions.’ The Local Norway, January 25, 2016. Available Online.

Local Sweden, The. 2015. Swedish nationalists cheer record poll support. The Local Sweden, December 1, 2015. Available Online.

Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (UDI). 2016. UDI-direktøren oppsummerte asylåret 2015 (med video) [UDI director summed asylum year 2015 (with video)]. Press release, January 7, 2016. Available Online.

---. N.d. Have Applied: Protection (asylum). Accessed February 2, 2016. Available Online.

Reuters. 2015. Factbox: Benefits offered to asylum seekers in European countries. Reuters, September 16, 2015. Available Online.

Statistics Denmark. N.d. Asylum applications and residence permits. Accessed January 15, 2016. Available Online.

Swedish Migration Agency. 2016. Applications for asylum received, 2015. Available Online.

---. 2016. While you are waiting for a decision. Last updated January 21, 2016. Available Online.

YLE. 2016. President Niinistö: Migrants pose challenge to Western values. YLE, February 3, 2016. Available Online.