You are here

Pacific Island Nations, Criminal Deportees, and Reintegration Challenges

A harbor in Vanuatu (Photo: Peace Corps)

Pacific Islanders who have committed criminal acts abroad and are deported have become a concern for the receiving countries as a significant number of deportees struggle to reintegrate. Pacific Islanders have historically tended to migrate to three main destinations: Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. In recent years these countries have toughened their immigration enforcement policies, with rising deportations one of the key results. Each of these countries has placed a growing emphasis on deporting individuals with criminal convictions. As part of this general pattern, hundreds of criminal deportees have been repatriated to their Pacific Island countries (PICs) during the past decade, following conviction for crimes including aggravated assault, burglary, and drug-related charges.

The deportation experience has implications not just for the receiving countries, but for the deportees themselves. This article explores research on the effects of deportation among Pacific Islanders as well as reintegration initiatives. Research throughout the region has found that criminal deportees are stigmatized and have difficulty reintegrating into community networks. Deportation may be the end of the immigration enforcement activity for these individuals, but it is also the start of a new and ongoing dilemma for individuals, families, the wider Pacific, and the international community.

|

Box 1. Countries and Territories of the Pacific Island Region

|

|

|

Pacific Islander Migration

The Pacific Island region is comprised of 22 countries and territories in the subregions of Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (see Box 1). International migration from and within the Pacific region, which has a long history, is currently developing, particularly to Australia and New Zealand, amid a mix of contemporary issues including declining natural resources, low-lying geographies that find their future threatened by climate change, and employment opportunities such as seasonal worker schemes.

Australian Bureau of Statistics data indicated that approximately 125,500 Pacific Island immigrants resided within Australia’s states and territories as of the 2011 census. The largest populations were from Fiji (56,980), Papua New Guinea (26,789), and Samoa (19,093).

Approximately 151,500 foreign-born Pacific Islanders lived in New Zealand, according to 2013 Census data. The largest populations were from Fiji (52,755), Samoa (50,661), and Tonga (22,416).

The United States has approximately 127,000 immigrants from the Pacific Islands, with the largest populations originating in Fiji (40,370), the Marshall Islands* (22,400), and Tonga (20,800), according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates (from 2013 for Fiji and Tonga, and 2010 for the Marshall Islands).

Deportation Policies Affecting Pacific Islanders Abroad

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) defines deportation as “the act of a State in the exercise of its sovereignty in removing an alien from its territory to a certain place after refusal of admission or termination of permission to remain.” Within this context, criminal deportation refers to the removal of an adult noncitizen (alien) after a conviction or admission of having committed a criminal offense in the state. Removal can occur irrespective of an individual’s length of settlement or personal/professional ties, although these may be taken into consideration when assessing individual cases.

The procedure in Australia, New Zealand, and the United States for deportation is similar in most cases: the individual may be detained and issued with a notice of deportation; he/she may then have a limited timeframe to contest the notice before being deported. Arguments used to prevent individuals from being deported relate to the length of residency, social and emotional ties, and hardship to family members. A further common thread among all three states: the discretionary power of government departments or specific public servants in determining the cancellation of removal in particular cases.

Deportations from Australia

Noncitizens may be deported under section 201 of the Migration Act of 1958, if convicted within ten years of entry of a criminal offense that draws a sentence of 12 months or more. Noncitizens can also be removed by having their visa cancelled or refused under the character grounds section 501, making the person unlawful. Under section 198, the unlawful noncitizen must be removed.

Deportation is used infrequently in Australia. Most removals occur when noncitizens have committed a severe criminal offense that results in cancellation of their visa.

|

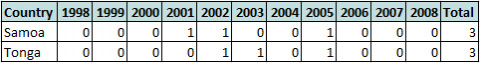

Table 1. Deportations from Australia to Samoa and Tonga, 1998-2008

|

|

Source: Australian Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) Program Integrity Risk Branch.

|

Deportation from New Zealand

New Zealand’s Immigration Act of 1987 provided for deportation for residence permit holders convicted of an offense, with removals occurring in the case of individuals who fail to leave New Zealand when their permit expired. Under the Immigration Act of 2009, the term deportation was broadened to describe all processes for requiring a foreign national who has no right to remain in New Zealand to leave (see Table 2).

New Zealand’s deportation policy follows similar priorities to those of the United States, with the removal of those involved in criminal offenses the “highest priority for deportation,” according to an Immigration New Zealand spokeswoman. Voluntary departure is the preferred method for removing those not convicted of criminal acts.

|

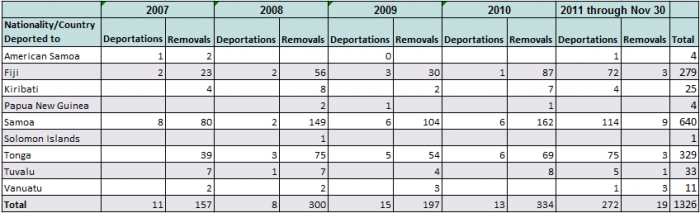

Table 2. Deportations and Removals from New Zealand to Pacific Island Countries, 2007-2011

|

|

Note: Department of Labour, Immigration New Zealand, Deportations and Removals (Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Labour, Immigration New Zealand, February 2012), www.immigration.govt.nz/NR/rdonlyres/FBE65871-110E-455A-9E6C-C8A349259DB7/0/Deportationsandremovals.pdf. |

Deportation from the United States

The range of criminal offenses for which noncitizens (unauthorized as well as those with lawful status) can be removed from the United States was substantially expanded in 1996 with passage of two federal laws: the Illegal Immigration Reform and Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) and the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA). Increased border and interior enforcement has resulted in approximately 400,000 annual formal removals since 2009. The government has placed greater emphasis on targeting unauthorized immigrants convicted of crimes in the United States, including those whose sole convictions are for immigration crimes or minor offenses. Criminal removals accounted for 80 percent of interior removals during fiscal years 2011-13.

Pacific Islanders have not been a particular target for removal, but individuals with criminal convictions have found themselves deported as part of the larger enforcement priorities (see Table 3).

|

Table 3. Removal of Criminal Aliens from Pacific Island Countries by the United States, FY 2004-13

|

|

Note: D indicates data withheld to limit disclosure. Beginning in 2008, criminals removed by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) are not included; the CBP ENFORCE database does not identify if aliens removed were criminals. Source: Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Immigration Statistics, 2013 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (Washington, DC: DHS Office of Immigration Statistics, 2014), www.dhs.gov/yearbook-immigration-statistics-2013-enforcement-actions. |

The Dearly Deported: Characteristics of Pacific Islander Criminal Deportees

Research published to date suggests that individuals deported for criminal offenses to Pacific Island countries are mostly males between 25 and 35 years of age. Most have spent more than 12 years away from their country of citizenship, making reintegration a significant issue. A substantial number are also separated from children and spouses/partners.

In Samoa and Tonga, individuals deported for criminal offenses were mostly males between 25 and 35 years of age (median age 28). The average length of time incarcerated in the host country (Australia, New Zealand, or the United States) was four years, with most serving less than two years in prison prior to deportation. The most common offenses were common/aggravated assaults, followed by aggravated robbery/burglary and theft/robbery/burglary, and third, drug-related charges. Thirty-seven percent have been investigated or charged following deportation; of those, almost half have served prison time, according to a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural (UNESCO) study.

The average length of time living outside of Samoa or Tonga prior to deportation was just over 20 years. Fifty-eight percent of criminal deportees interviewed in the UNESCO study indicated having spouses/partners residing overseas, while 50 percent said they had one or more children living abroad.

In the Marshall Islands, criminal deportees were mostly men between 25 and 30 years of age. The average length of time incarcerated in the United States (100 percent of participants in a forthcoming study by UNESCO and IOM were deported from the United States) was just over two years prior to deportation. Aggravated felony was the final charge description for most individuals deported to the Marshall Islands, followed by crimes involving moral turpitude. Sixteen percent reported being investigated or charged with a criminal offense following deportation; of those, 12 percent were incarcerated in the Marshall Islands.

The average length of time living outside of the Marshall Islands was 14 years. Of those who participated in the forthcoming study, 55 percent consider themselves to be single; 89 percent stated that their child/children do not live in the Marshall Islands, demonstrating a high rate of parent-child separation.

Barriers to (Re)Integration

Reintegration barriers for individuals deported for criminal offenses are significant, as social welfare programs are often unavailable. Community support networks developing from family ties and communal living provide the critical safety-net role in the Pacific. This community social net provides for people who cannot support themselves due to age, illness, or other circumstances through the redistribution of resources. Individuals who have been deported for criminal offenses have not, for the most part, grown up within these communities, and although family ties may exist, they do not guarantee access to this form of social support. Ill health, unemployment, and a lack of income may therefore be difficult issues for deportees who face limited or no access to social support networks.

Social dislocation upon arrival and throughout settlement is also a key factor affecting reintegration and the attainment of employment or education; many deportees, particularly those in Samoa and Tonga, reported poor local language skills and cultural connectedness.

A deportation record can be a tremendous disadvantage in gaining meaningful employment, particularly in a region with small labor markets and significant unemployment or underemployment. In addition, labor conditions and pay rates are lower than those in the deporting countries, thus limiting the opportunities for deportees to remit wages to children and/or spouses overseas.

Marginalization and discrimination from local communities that express shame, fear, and rejection of deported individuals represent another significant reintegration issue. There is a perception that individuals deported for criminal offenses are inherently corrupt and will continue their criminal activity. Deportees with tattoos and who may have belonged to gangs report being victimized, particularly through over-policing and discrimination when attempting to meet basic necessities such as securing accommodation.

While Pacific-wide statistical data are not available for the number of women deported to the region, the small number of female deportees who participated in national studies represents a vital source of information. These women indicated being exposed to sexual and physical violence from an early age. Their crimes were most often drug-related, and upon return to the Pacific Islands they reported experiencing unstable or insecure living arrangements, separation from children and/or spouses, and in some instances mental health issues.

Women deported for criminal offenses have been identified as an at-risk group by international organizations such as UNESCO, due to their increased vulnerability to gender-based violence and sexual or labor exploitation (particularly in unprotected informal sectors such as domestic work). Female deportees may also face restricted access to income-generation activities due to limited familial or community links.

The Pacific Approach to Deportee Reintegration

The strategy to reintegrate criminal deportees has been two-fold: at one end, a law enforcement approach that sees programmatic aid tied to specific law and justice outcomes, and at the other, an approach based on social integration. National governments, civil-society organizations (CSOs), and regional and international organizations have undertaken various initiatives within these approaches. At the country level, Tonga and Samoa have led the way, establishing government-mandated initiatives to coordinate and provide services to individuals deported for criminal offenses.

Tonga paved the way in 2008 with a high-level workshop on deportation that resulted in support for social welfare activities such as income generation, counseling, and family reunification to assist with reintegration. However, limited financial assistance, lack of community support, and internal restructuring ceased the operations of the two CSOs providing reintegration services: the Ironman Ministry Inc. and the Foki ki ‘Api Deportation Reconnection program organized through the Tonga Lifeline Crisis Ministry of the Free Wesleyan Church.

In 2010, Samoa advanced work on the issue through the Office of the Attorney General, which established a Criminal Deportee Task Force to coordinate national law enforcement activities. With the government’s endorsement and assistance from regional partners such as UNESCO, the task force established the Samoan Returnee Charitable Trust. The Trust’s aim is to provide reintegration services such counseling and a range of community awareness activities. Currently, it is engaging donors and other partners to seek further funding for its activities.

Regional organizations, including the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat (PIFS) and the Pacific Islands Chiefs of Police (PICP), have also shed light on reintegration concerns through the provision of internal reports for member states and members of the Forum Regional Security Committee. In 2007-8, a PIFS scoping study found a lack of national policies and coordination mechanisms among governments for managing criminal deportations, the stigmatization of deportees by receiving communities, and a lack of community services for deported individuals. In 2010, the PICP undertook a Criminal Deportees Project to determine the impact of deported individuals on criminal activity; internal recommendations on how this could be minimized were made to PICP member countries.

Deported individuals in UNESCO-led national consultations in Samoa and Tonga identified specific programs that would assist in their reintegration, with the top three being requests for assistance in employment, job training and educational courses, and counseling/therapy.

The Future

The phenomenon of criminal deportation to the Pacific is likely to continue into the foreseeable future as noncitizen populations of Pacific Islanders remain in Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, and host countries continue to prioritize criminal removals. As a result, the Pacific region will continue to receive individuals who have been deported for criminal acts.

Continuing financial and technical provision to build mechanisms that support deportees through the period of arrival and (re)integration in Pacific Island countries will assist in enabling individuals to become responsible, contributing members of their communities, and in preventing possible continued involvement in criminal activities.

* Marshall Islanders are admitted to the United States to live, work, and study as nonimmigrants, and generally do not have a path to permanent residency or citizenship. They are thus not formally considered immigrants.

Sources

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). 2011. 2011 Census of Population and Housing. ABS TableBuilder. Available Online.

Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Immigration Statistics. 2014. 2013 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Washington, DC: DHS Office of Immigration Statistics. Available Online.

Department of Labour, Immigration New Zealand. 2012. Deportations and Removals. Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Labour, Immigration New Zealand. Available Online.

Duke, Michael. 2014. Marshall Islanders: Migration Patterns and Health-Care Challenges. Migration Information Source, May 2014. Available Online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2004. International Migration Law: Glossary on Migration. Geneva: IOM. Available Online.

Leask, Anna. 2012. Samoa, India and China top deportation list. The New Zealand Herald, October 25, 2012. Available Online.

Pereira, Natalia. 2010. Return[ed] To Paradise: The Deportation Experience in Samoa and Tonga. Apia, Samoa: UNESCO. Available Online.

Pereira, Natalia and Siobhan McNamara. 2012. Working with Deported Individuals in the Pacific: Legal and Ethical Issues. Suva, Fiji: UNDP Pacific Centre. Available Online.

Pereira, Natalia, Isabel Inguanzo-Ortiz, Kate McDermott, Tim Langrine, and Angela Saunders. Forthcoming. "Kem Ej Ri-Majol Wot" "We are still Marshallese": The Deportation Experience in the Republic of Marshall Islands. Bangkok, Thailand: UNESCO and IOM.

Rosenblum, Marc R. and Kristen McCabe. 2014. Deportation and Discretion: Reviewing the Record and Options for Change. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available Online.

Statistics New Zealand. 2013. 2013 Census of Population and Dwellings. NZ Stat. Available Online.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2013. 2013 American Community Survey. American Fact Finder. Available Online.