You are here

Paying for Protection: Corruption in South Africa’s Asylum System

Asylum seekers and refugees line up at a refugee reception office in South Africa. (Photo: Lawyers for Human Rights)

South Africa’s 1994 transition to democracy ushered in a series of progressive laws, including those governing immigration and asylum, to reflect the country’s new rights-based constitution. These liberal-leaning laws quickly gave way to the practicalities of governing a country with high levels of poverty, unemployment, and socioeconomic deprivation. And as South Africa faced new levels of migration from the region, policy interests quickly diverged from legal obligations under the country’s Refugees Act of 1998.

South Africa hosts more than 576,000 refugees and asylum seekers, many of whom fled conflict and persecution in the region, including from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, Burundi, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Zimbabwe, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The government has recognized approximately 65,000 refugees, while 230,000 asylum seekers were awaiting decisions at the end of 2013, according to figures from South Africa’s Department of Home Affairs (DHA). Large backlogs and overwhelming demand have allowed systemic corruption to flourish in the asylum system. As asylum seekers and refugees have confronted barriers at multiple turns, some have lapsed into irregular status—making them increasingly vulnerable to detention and deportation in a climate of heightened immigration enforcement.

Drawn from a series of studies by the author, including a recent survey of 928 asylum seekers and refugees, this article examines the development and implementation of asylum and refugee policy in South Africa since democratization. While the law conforms to international and regional standards of protection, in practice daily operations are characterized by inefficiency, violations of administrative justice, and corruption, with asylum seekers and refugees often required to pay bribes just to enter a refugee reception office, let alone acquire proper documentation. Furthermore, the government’s view of all migrants, including asylum seekers, as security threats has led to increased detention and deportations, with implications for protection, individual rights, and good governance.

Post-Apartheid Asylum Policy

South Africa’s apartheid government had greatly restricted migration from Africa, with the exception of tightly controlled labor migration arrangements. The country lacked a refugee policy before the government entered into a memorandum of understanding in 1997 with UNHCR, which was followed by the passage of the Refugees Act the following year. The new refugee policy was progressive in many ways. It adopted the refugee definition found in the international Refugee Convention and incorporated the expanded understanding of the Organization of African Unity’s refugee convention, developed in response to large-scale instability in the region. The latter provision grants refugee status to individuals fleeing “events seriously disturbing or disrupting public order.” South Africa’s domestic legislation also explicitly included gender and sexual orientation in the definition of “social group” eligible for refugee protection. Finally, the new legislation departed from practice in the region by relying on urban integration of refugees rather than encampment, providing for detention only in exceptional circumstances. The urban integration approach entitles both refugees and asylum seekers awaiting final adjudication of their claims to legally reside, work, and study in the country.

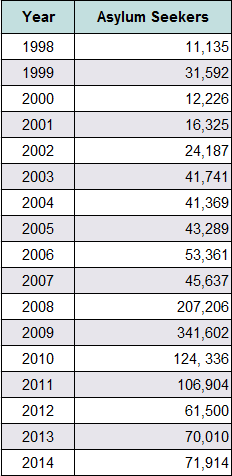

Table 1. Number of Asylum Applications Filed Annually in South Africa, 1998-2014

Source: Department of Home Affairs, Annual Asylum Statistics.

The new system, operating on the basis of individualized assessments, lacked the capacity to deal with rising asylum applications and became overwhelmed, particularly as the numbers began surging. From 2006-11, UNHCR identified South Africa as the top recipient of asylum seekers in the world. The number of new asylum seekers reported by DHA rose from about 11,000 in 1998 to more than 341,000 in 2009, stabilizing around 70,000 in 2013 and 2014 (see Table 1). Though annual inflows were initially fairly low, backlogs in the processing system began early on. Emerging from the closed apartheid system, the government had not anticipated the arrival of large numbers of asylum seekers, a situation that was exacerbated by deteriorating political and humanitarian conditions in neighboring Zimbabwe.

Almost from the start, politicians and the public alike questioned the liberal refugee framework as migration to the country increased. Lesser-skilled migrants from neighboring countries also began entering South Africa in search of economic opportunity. The new immigration policy did not provide them with legal channels for work, so these lesser-skilled economic migrants turned to the asylum system alongside genuine asylum seekers, capitalizing on the minimal barriers to entry and the work entitlement granted to asylum applicants while their claims are being processed. The high demand crippled the system. The situation benefited economic migrants, who could continue to work during the long adjudication and appeals process, even as those genuinely in need of protection lived in uncertainty for years as their claims worked their way through the inundated and backlogged system. Often, those in the latter category were also hastily labelled economic migrants by officials struggling to disqualify individuals as quickly as possible. DHA routinely claimed that 95 percent of those in the asylum system were economic migrants, but a 2011-12 survey of 1,417 asylum seekers conducted by the author called this number into question—with roughly 50 percent reporting that they had left their countries of origin solely for economic reasons (in a 2007-8 survey by the author, this number was 29 percent).

The high number of applicants sparked calls to tighten the asylum system, with formal efforts to amend the Refugees Act beginning in 2008. The most recent amendments, proposed in 2015, would greatly restrict the rights of refugees and asylum seekers. The government has long claimed that economic migrants are exploiting the permissive asylum system and are largely responsible for the country’s socioeconomic ills. Even before specifically targeting the asylum system, policymakers for years have warned of an influx of migrants. In 1997, the first Minister of Home Affairs—the department in charge of immigration and asylum—invoked an exaggerated number of 2.5 million to 5 million irregular migrants whom he accused of having a dire effect on “housing, health services, education, crime, drugs, transmittable diseases,” and “undermining the welfare of the country.” Similar sentiments were soon applied to an increasingly unwieldy asylum system, with policymakers and the public often conflating asylum seekers, economic migrants, and irregular migrants.

As anti-migrant views prevailed, asylum policy and practice increasingly diverged from the promise of the refugee legislation, while the government continued to rely on inflated migrant numbers to justify departures from the law in order to exercise a stronger hand in removing migrants. Legal cases and research by the author reveal that the DHA often deports asylum seekers extra-legally, without adherence to the required legal procedures, defending these practices on security grounds while failing to provide details. Migrants deported from the border are often not recorded in official deportation statistics. State policy has increasingly engaged with asylum issues in security terms, rather than in the humanitarian terms espoused by the Refugees Act. This policy regards asylum seekers as potential threats and abusers of the system as opposed to a population in need of protection. In 2012, the ruling African National Congress (ANC) released a policy document calling for a “risk-based approach” to asylum to ensure the country’s stability and national security based on the government’s belief—not substantiated by evidence—that criminal syndicates and human smugglers were exploiting the overburdened asylum system. The approach included plans to increase detention of “high-risk” asylum seekers, introduce monitoring mechanisms for all applicants, and refuse asylum to individuals who transited other safe countries en route to South Africa. The document faulted the unconditional adoption of international and regional instruments during the democratic transition in the 1990s for failing to take into account migration realities and to recognize migration as a national security issue.

Box 1. Rights of Asylum Seekers and Refugees in South Africa

Asylum seekers and refugees are entitled to most of the same human rights under the constitution as South African citizens. This includes the right to seek employment, move freely within the country, and access primary education and medical care, but excludes the right to vote or form a political party.

Once individuals’ asylum applications are approved, they are granted refugee status and issued a renewable permit valid for two years. Individuals with refugee status may apply for permanent residence after five years of continuous residence following certification that they will remain refugees indefinitely.

Restricting Access to the Asylum System

Asylum seekers must lodge an asylum claim at one of three refugee reception offices (RROs) open to new applicants. Management and capacity issues at these offices have hindered daily operations, as documented by previous research and investigations by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and acknowledged to a certain extent by the government. However, rather than reforming the immigration policy that contributed to unmanageable queues and backlogs in the tens of thousands of claims, or devoting greater resources to improving the system’s capacity, DHA has concentrated on greater immigration enforcement and has targeted the migrants themselves. The department embarked upon a variety of practices and legal interpretations aimed at restricting access to the asylum system, limiting who qualifies as an asylum seeker, and increasing the barriers to maintaining documentation for both asylum seekers and registered refugees. Without this documentation, asylum seekers and refugees are barred from accessing jobs, bank accounts, education, health care, housing, and other services. They also risk detention and deportation, despite the principle of nonrefoulement (which forbids the return of refugees to a state in which they have good reason to fear persecution).

In defiance of the high demand, DHA closed three of the country’s seven urban RROs. This move prevented many would-be asylum seekers from obtaining or maintaining documentation and accompanying legal protections. Applying at another office would necessitate returning to that office roughly every three months to renew asylum documents. Many existing asylum seekers also lost their status, amid difficulties traveling to more distant RROs before their documents expired. The travel requirement poses a particular burden for asylum seekers, who often work in precarious positions and must take several days off to not only reach an RRO but to gain entry to the office, as there are often long lines outside, specified days for nationals of certain countries, and corrupt actors barring access. In addition to the financial burden, many lack flexibility to schedule time away from work and risk losing their jobs. Children must also travel with their parents to renew their documents. The financial burden is compounded by DHA’s practice of imposing prohibitive fines on individuals who seek to renew their permits after the expiration date, even in cases when the delay was caused by long queues that prevented access to the RRO.

Alongside these barriers, DHA has adopted restrictive legal interpretations in defense of its efforts to prevent access to the asylum system. Despite legal guarantees and judicial rulings to the contrary, DHA has disqualified individuals arrested before they reach an RRO from applying for asylum even if they state an intention to apply. The department has claimed that it has no obligation to assist an individual it deems an “illegal foreigner” to apply for asylum, a view that flouts judicial interpretations and ensures exclusion. These and other legal interpretations have worked to categorize a growing number of existing and would-be asylum seekers as illegal foreigners in order to remove them from the purview of the asylum system.

Daily operations at RROs are characterized by procedural irregularities and corruption, creating further obstacles to the acquisition and maintenance of asylum and refugee status and documents, according to academic research and periodic investigations by journalists and NGOs working with the affected population. The failure to address growing demand at the RROs has led to a slate of well-documented problems around access, service, and administrative fairness. Individuals are often forced to wait in line overnight or return multiple times before gaining entry. Once inside, asylum seekers confront arbitrary and capricious decision-making by officials, including the sudden withdrawal or cancellation of documentation, refusal to accept appeal requests, denial of entry for appeal hearings, and appeal rejections following hearings held in absentia without notification of the hearing date. Asylum seekers may undergo status-determination interviews on the first day they apply and often do not understand the process or their rights. Many remain similarly unaware of their rights of appeal.

The status-determination process itself is also highly flawed. Surveys of asylum seekers and refugees and a review of hundreds of status-determination decisions by the author show that status-determination officers conduct short, cursory interviews and issue rote, often cut-and-pasted decisions that invariably contain legal and factual errors. These include reliance on the wrong burden and standard of proof and the exclusion of many of the legal bases for refugee status found in the Refugees Act. Decisions routinely contain inaccurate or outdated country information. Some decisions detail country information that supports the asylum claim followed by a rejection without explanation. Many decisions lack reasons altogether, or refer to the wrong claimant or country. Status-determination officers often issue identical decisions to a number of claimants without addressing their individual claims. Asylum seekers who recount tales of torture, sexual and gender-based violence, or other forms of persecution are rejected on the grounds that they suffered no harm and did not have a well-founded fear of persecution. Roughly 90 percent of asylum claims are rejected amid these problematic procedures. Despite the fact that there is generally no link between an individual’s asylum claim and the decision rendered, DHA characterizes these claimants as economic migrants and uses this figure to justify further restrictions on the asylum process.

Corruption at the Refugee Reception Offices

Rather than address RRO service issues and capacity limitations, DHA has maintained a steadfast focus on decreasing the number of individuals entering the asylum system. The current conditions in which individuals struggle to access services at RROs and cannot obtain a status-determination decision that truly reflects their protection needs create a fertile ground for corruption. As a result, corruption has become endemic. Office closures have increased demand pressures, further narrowing the space for obtaining documentation while increasing the incentives and demand for payments. In its response to corruption, DHA has not taken into account the link between the quality and management issues described above and the flourishing of corruption.

Following the publication of a report by the author showing rampant corruption at the RROs, DHA announced the launch of Operation Bvisa Masina (“throw out the rot”) in summer 2015 to target corrupt Home Affairs officials, including a multidepartmental response team to target the most corrupt office. At this office—the Marabastad RRO in Pretoria—62 percent of respondents reported experiencing corruption. As of September 2015, DHA reported 26 arrests as part of this operation, but no convictions. DHA has not publicized any additional details on the operation. Meanwhile, the systemic conditions leading to corruption at the RROs continue.

In the corruption study—a survey of 928 individuals waiting outside the country’s five remaining RROs (the Cape Town office remains open to existing asylum seekers, but not new ones)—close to one-third of respondents reported experiencing corruption at some stage of the asylum process—more than four times on average. Asylum seekers and refugees experienced corruption at multiple stages, beginning with entry into the country and continuing once they arrived at an RRO. They reported corruption, in the form of demand for bribes, at every point of the process: queuing, obtaining and renewing asylum documents, and obtaining and renewing refugee documents. The corruption did not stop even after an individual obtained refugee status, with refugee-status renewals and other services also linked to a demand for unofficial payments. The respondents implicated various actors in the asylum system, including security guards, interpreters, refugee reception officers, refugee status-determination officers, police officers, and private brokers with links to DHA officials. Many respondents reported that they had at some point been unable to access the office or renew their documents because of an inability to pay. Many remained undocumented because they could not pay, placing them at risk of detention and deportation. One respondent described the situation: “The people don’t care who you are, where you come from, what your story is. They just care about money. If you have got money, everything is good for you.”

The survey results show that corruption is systemic, but DHA has been largely reactive and responded only to individual allegations of corruption rather than contemplating systemic change. In dealing with individual allegations of corruption, DHA places much of the investigatory burden on the asylum seekers themselves; the process occasionally results in the removal of a corrupt individual, but more often the investigation is abandoned. Asylum seekers who complain are often greeted with indifference and may themselves be targeted for investigation. Thus DHA’s anticorruption efforts have done little to alleviate the structural problems that allow corruption to flourish. The ineffectual response has left asylum seekers and refugees with the stark choice of paying for access and services, or remaining undocumented at great personal risk. Even those who are in the system legitimately may ultimately be forced to turn to illegitimate means to obtain protection.

The Implications of Corruption

The wide-scale corruption and administrative irregularities at RROs are the product of a deliberate government choice to target demand for asylum in isolation, at the expense of improving services or addressing broader migration issues. The situation, however, has implications not only for asylum seekers, but also for migration policy, a rationally functioning public service, and for governance itself.

While South Africa’s migration policy remains focused exclusively on the restrictive measures of border control, detention, and deportation, the failure to address corruption has thwarted these efforts by providing an incentive for irregular migration. The delinking of refugee status from protection needs has undermined the government’s migration management goals and provided a mechanism for economic migrants to enter the country and take advantage of corrupt practices to regularize their status, even as the government devotes greater resources to border control and deportation to prevent just this type of migration. While the government continues to point to the scourge of economic migrants abusing the asylum system, it does little to combat the corruption that enables individuals without protection needs to claim asylum even as it denies protection to the system’s intended beneficiaries.

The government’s singular focus on tightening restrictions in the asylum system has transformed this system into a mechanism of migration control—one that fails to provide protection in accordance with international and constitutional obligations. At the same time, this move increases the market for and susceptibility to corruption. The result is an asylum practice that is no longer bounded by legal guarantees but is instead guided by monetary incentives.

Sources

African National Congress (ANC). 2012. Peace and Stability: Policy Discussion Document. Johannesburg: ANC. Available Online.

Amit, Roni. 2009. National Survey of the Refugee Reception and Status Determination System in South Africa. Johannesburg: Forced Migration Studies Programme (FMSP). Available Online.

---. 2010. Protection and Pragmatism: Addressing Administrative Failures in South Africa’s Refugee Status Determination Decisions. Johannesburg: FMSP. Available Online.

---. 2012. All Roads Lead to Rejection: Persistent Bias and Incapacity in South African Refugee Status Determination. Johannesburg: African Centre for Migration & Society (ACMS). Available Online.

---. 2012. No Way In: Barriers to Access, Service and Administrative Justice at South Africa’s Refugee Reception Offices. Johannesburg: ACMS. Available Online.

---. 2015. Queue Here for Corruption: Measuring Irregularities in South Africa’s Asylum System. Johannesburg: Lawyers for Human Rights and ACMS. Available Online.

Buthelezi, Mangosuthu G. 1997. After Amnesty: the Future of Foreign Migration in South Africa. Keynote Address, Southern African Migration Project Conference, Cape Town, June 20, 1997. Available Online.

Department of Home Affairs (DHA). 2014. Department of Home Affairs: Annual Performance Plan 2014-2015. Johannesburg: DHA. Available Online.

---. 2015. Statement by Minister Gigaba at the Media Briefing on the Department’s Counter-Corruption Measures, July 24, 2015. Media release, July 27, 2015. Available Online.

---. N.d. Refugee Status & Asylum. Accessed October 21, 2015. Available Online.

Legal Resources Centre (LRC). 2015. Migrants Guide to Asylum and Immigration Systems. Johannesburg: LRC and Coram Children’s Legal Centre. Available Online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2015. 2015 UNHCR Country Operations Profile – South Africa. Accessed October 21, 2015. Available Online.