You are here

“Us” or “Them”? How Policies, Public Opinion, and Political Rhetoric Affect Immigrants’ Sense of Belonging

Welcoming immigrants at a rally in Hamburg, Germany. (Photo: Rasande Tyskar)

It is no overstatement to say that immigrant integration is a highly salient topic in most contemporary Western democracies, with the emphasis long on issues of labor market incorporation, language acquisition, and economic mobility. While more recently there has been a strong focus on more subjective questions of integration, particularly around issues of identity and embrace of national values, the question of whether immigrants themselves feel they are a part of the broader society has until recently received less attention. As immigrant identities are scrutinized and politicized in Europe, in particular in an era of increased polarization around the issue of migration, debates questioning immigrants’ willingness and capability to become part of their new country underscore how important belonging actually is.

Efforts to define national character and national values accompany the focus on immigrants’ identifications. Debate about what it means to be part of “our” community is a question that takes center stage in many countries in response to concerns over immigrant integration. While majority-group nationals may disagree about how to define the boundary between “us” and “them,” these boundary definitions tend to gravitate around shared understandings of nationhood that set one nation apart from the other. It is not difficult to imagine the contrast in responses one would get from asking a group of French people what it means to be French, compared to asking some Germans what it means to be German.

This article examines whether the way in which a national boundary is defined—by politicians and ordinary people alike—matters for immigrants’ feelings of belonging. The boundaries at issue are not physical (such as the lines between different geographical areas), but conceptual: the distinctions we make to categorize groups of people. While it may seem obvious that immigrants will find it easier to belong in national communities where membership is defined in more inclusive terms, it is not entirely clear what that would entail and whether different types of boundaries are equally important for immigrants’ belonging. The research examined here suggests that, contrary to what we should expect based on the popular and scholarly attention citizenship policies receive, they are less important for immigrants’ belonging than the boundaries drawn through popular conceptions of nationhood and political rhetoric.

Why Care About Immigrant Belonging?

Belonging involves both identification with and feelings of attachment to a social community. While many people are able to take national belonging for granted, this is often less straightforward for immigrants and even for their children born in the new country. A critical question is whether it is actually important that immigrants feel belonging to the nation. While many can function well without feeling a strong sense of national attachment—and belonging to a new nation is not necessarily at odds with feeling attachment to one’s origin country—scholars recognize belonging can confer important benefits for both the individual immigrant and the immigrant-receiving society.

Belonging to a social community is found to enhance individuals’ sense of meaning in life, while experiences of social exclusion lead to lower self-worth, and even meaninglessness. Scholars argue that the nation is a particularly central contemporary community because it gives form to our everyday lives, even without most of us realizing it: News is communicated through a national lens and in the national language; we learn about the nation’s history, culture, and institutions in school; we support “our” national sports teams, and so on. This makes the nation a stable and coherent object of belonging in a world that many perceive as fragmented and in flux. National attachment therefore provides people with a basic sense of safety. In addition, being recognized by others as someone who belongs involves feelings of worth, legitimacy, and status; in short, the immigrant and the national-majority individual become equal partners for social interaction.

At the societal level, a common national identity has been found to contribute to community cohesion and encourage cooperation and societal engagement. Given the negative individual-level effects of social exclusion, some theorists also hypothesize the development of counter-cultures in response to blocked identity aspirations, such as when immigrants experience being denied recognition as fellow nationals.

Given these positive effects, the interesting question is whether belonging is easier in some contexts rather than others, depending on the boundaries drawn around the nation.

Citizenship Policy: Do Fewer Restrictions Signal a More Accepting Society?

Boundaries of national membership exist in different forms—whether formal or informal—and are formulated by different actors, such as politicians or the majority population. Formal boundaries are official policies designed to define membership, such as citizenship, voting rights, or employment policies.

The foremost example is citizenship policy, which sets the criteria for who may become an officially recognized member of a particular country. The restrictiveness of citizenship policies varies considerably across Western nation-states as do the signals these policies communicate about the type of knowledge and behavior one must comply with to become part of the nation. To become a citizen of Austria, for example, one must have ten years of residency, be economically self-sufficient, speak German, pass a knowledge test on Austrian history and the principles of the democratic system, and resign any previous citizenship. In Sweden, none of these requirements applies, except for length of residency (and here it is just five years), and dual citizenship is allowed. Scholars often point to citizenship policy as a signifier of a country’s openness or closedness toward newcomers. In this way, it could be expected that immigrants would find it easier to belong in countries with more liberal citizenship regimes.

A 2016 study by the author examined whether the substantial variation in the citizenship policies of Western democracies matter for the extent to which immigrants to different countries feel national belonging. The study used data from 19 Western democracies collected during two different years (2003 and 2013), data from the Migrant Integration Policy Index, and survey answers from first- and second-generation immigrants about the degree to which they feel close to the nation in which they live.

Surprisingly, the study offered no evidence to support the hypothesis that citizenship policy affects immigrant minorities’ national belonging. Other experts have come to similar conclusions in their research on civic integration and multicultural policies: In two studies by Goodman & Wright and Bloemraad & Wright, despite substantial variation over time and space in the use of civic integration and multicultural policies, these policies did not appear to foster (nor hinder) immigrants’ generalized trust and perceived discrimination.

One potential reason for the lacking effect of citizenship (and other types of integration) policy is that it is composed of various requirements—such as length of residence, economic self-sufficiency, language skills, and resigning one’s previous citizenship—making it difficult for the individual immigrant to assess exactly how open or closed a given national community is. In addition, there may be great variation across immigrants in how difficult it is for them to live up to the demands. In other words, while one type of immigrant may find the host country’s citizenship policies exclusive, others may find it relatively easy to live up to them.

Popular Ideas of Belonging

Boundaries are not only defined in formal terms through citizenship or integration policies, but also more informally in conceptions of nationhood shared among members of a society. While these boundaries are not officially sanctioned, they are not any less powerful as signals of inclusivity/exclusivity. In particular, how majority nationals define the boundary of the national community likely affect everyday encounters with immigrant minorities.

In the study mentioned above, the author also analyzed the potential effects of popular conceptions of nationhood by using survey responses to measure the nonimmigrant majority population’s boundary drawing in the 19 countries studied.

The author found the criteria valued for being considered part of the national community clustered in two groups: ascriptive and attainable criteria.

- Ascriptive criteria include being born in the country, having lived in the country for most of one’s life, having host-nation ancestry, and being of the host nation’s religion. These criteria are impossible to acquire if one does not have them in the first place. Of course, religious conversion is in principle a possibility but the fact that this criterion groups with the other ascriptive criteria suggests that most people consider religion a permanent trait of individuals.

- Attainable criteria include language skills in the host country’s official language(s), citizenship, respecting the country’s laws and institutions, and feeling like a national. These criteria are possible to acquire, at least over time.

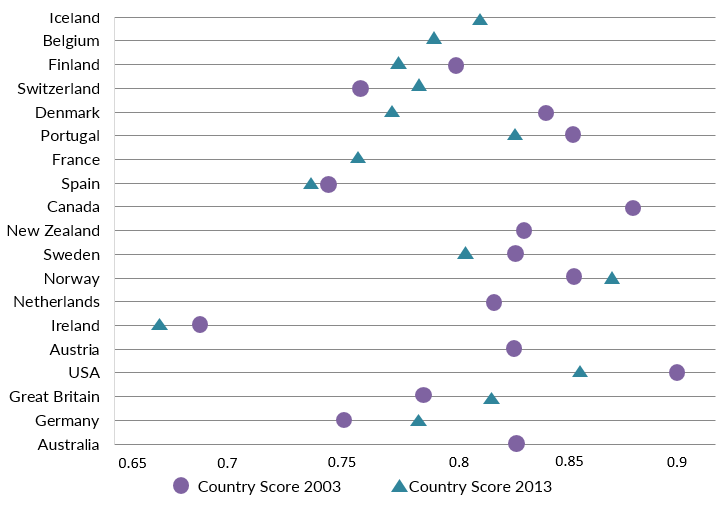

Figures 1 and 2 show the value of importance assigned to the two groups of criteria in each country in 2003 and 2013, using a 0-1 scale, where 0 means not important at all, and 1 means very important. As can be seen, the values vary quite substantially across countries while the within-country variation over time is rather small for most countries, suggesting that conceptions of nationhood are relatively stable over time.

Figure 1. Importance of Criteria Immigrants Cannot Obtain to Select Countries

Source: Kristina Bakkær Simonsen, “How the Host Nation’s Boundary Drawing Affects Immigrants’ Belonging,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42, no. 7: 1153-76.

Figure 2. Importance of Criteria Immigrants Can Obtain to Select Countries

Source: Bakkær Simonsen, “How the Host Nation’s Boundary Drawing Affects Immigrants’ Belonging.”

In contrast to citizenship policy, popular conceptions of nationhood have significant effects on immigrant minorities’ national belonging in the study. In particular, first- and second-generation immigrants’ national belonging is greater in countries where the majority population places high value on attainable boundary criteria, such as the United States, France, and Canada. In other words, boundaries can be positive when they signal to immigrants their being welcome to belong, upon having met a set of feasible requirements, such as acquiring language skills and respecting the country’s norms and laws.

In a similar study based on survey data from 18 Western European countries in the period 2002-12, the author found further support for the importance of public opinion. In countries where the majority population hold negative and denigrating opinions of foreign-born residents, such as Greece, Great Britain, and Portugal, immigrants perceive themselves to be discriminated against to a much larger degree than in countries where majority opinions are more positive and acknowledging.

These results offer an additional perspective for interpreting the lacking policy effect: While immigrants are likely confronted with majority nationals’ ideas of “us” and “them” on an everyday basis, policy signals are typically salient only when individuals are directly confronted with the law, for instance, in the process of applying for citizenship. The author’s qualitative work based on interviews with immigrants and their children support this interpretation, as interviewees referred to mundane and seemingly innocent everyday experiences—such as praise for their language skills or being asked “Where do you come from?”—when talking about their impressions of the national boundary. Official policies rarely come up, and, if they do, mainly when prompted directly by the interviewer.

The Damaging Effects of Political Rhetoric

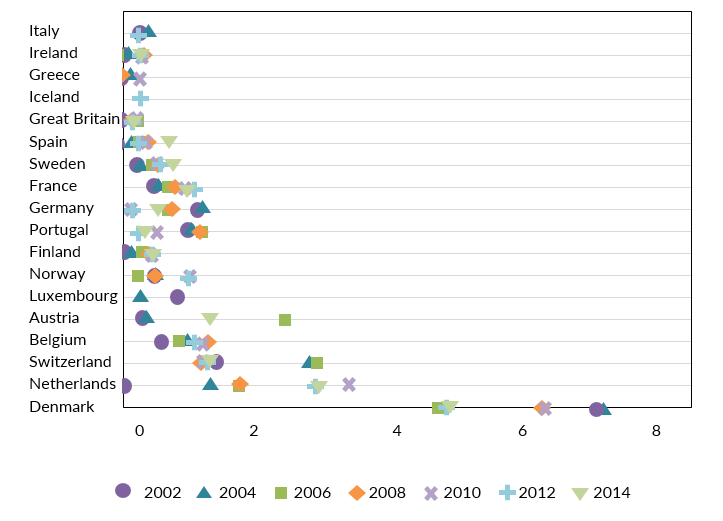

While politicians’ official boundary drawing, via policy, does not seem to be as important as hypothesised for signaling inclusivity or exclusivity, they also draw boundaries informally through the rhetoric they use about the nation and newcomers’ place in it. In an American case study from Pérez, Latino political trust and political values were negatively affected when confronted with xenophobic political rhetoric. Switching the perspective to Western Europe, the author explored the potential effects of anti-immigrant political rhetoric from 2002-14 in a forthcoming paper that demonstrated the damaging effects on first- and second-generation immigrants’ political trust and faith in the country’s democratic system. The study is based on party manifesto data to construct a measure of negative political rhetoric, coupled with survey data on immigrants’ evaluations of the national political community. There is substantial variation in the salience of anti-immigrant political rhetoric, with Danish politicians using this type of rhetoric most extensively (see Figure 3). Perhaps most (in)famous is the rhetoric of the extreme right-wing Danish People’s Party, but other high-profile politicians also express negative views of immigrants. For instance, the current Minister of Foreigners and Integration, Inger Støjberg, has repeatedly underscored that it should be difficult to become Danish.

Figure 3. Negative Political Rhetoric

Source: Kristina Bakkær Simonsen, “The Democratic Consequences of Anti-Immigrant Elite Rhetoric: A Mixed Methods Study of Immigrants’ Political Belonging” Political Behavior (forthcoming).

In addition to the general result, the study shows that the damaging effects of political rhetoric are particularly strong for Muslims and immigrants with fewer years of education. This suggests a sophisticated processing of politicians’ informal boundary drawing: Immigrants respond to the particular content of political messages, with the immigrant groups most in focus of negative political rhetoric in contemporary Europe being most negatively affected.

Policies Less Effective than Public Opinion and Political Rhetoric

Citizenship and integration policies have received much political, public, and scholarly attention in recent years—and with good reason as they have consequences for immigrants’ formal rights and possibilities. However, the research discussed in this article suggests that the signaling effects of such policies have been overestimated, at least for immigrants. Instead, research points to the importance of boundaries at the informal level, drawn through talk and signaling by majority nationals and politicians about conceptions of the nation. While immigrants must invest in belonging, integration is a two-way street, and it is clear from the evidence that the majority society has a role in making immigrants’ belonging possible.

Sources

Bail, Christopher. 2008. The Configuration of Symbolic Boundaries against Immigrants in Europe. American Sociological Review 73 (1): 37-59.

Bonikowski, Bart and Paul DiMaggio. 2016. Varieties of American Popular Nationalism. American Sociological Review 81 (5): 949-80.

Brubaker, Rogers. 1992. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Goodman, Sara Wallace and Matthew Wright. 2015. Does Mandatory Integration Matter? Effects of Civic Requirements on Immigrant Socio-Economic and Political Outcomes. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (12): 1885-1908.

Lamont, Michèle and Virág Molnár. 2002. The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences. Annual Review of Sociology 28: 167-95.

Lamont, Michèle, Graziella Moraes Silva, Jessica S. Welburn, Joshua Guetzkow, Nissim Mizrachi, Hanna Herzog, and Elisa Reis. 2016. Getting Respect. Responding to Stigma and Discrimination in the United States, Brazil, and Israel. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Pérez, Efrén O. 2015. Ricochet: How Elite Discourse Politicizes Racial and Ethnic Identities. Political Behavior 37 (1): 155-80.

---. 2015. Xenophobic Rhetoric and Its Political Effects on Immigrants and Their Co-Ethnics. American Journal of Political Science 59 (3): 549-64.

Simonsen, Kristina Bakkær. 2016. How the Host Nation's Boundary Drawing Affects Immigrants' Belonging. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (7): 1153-76.

---. 2016. Ripple Effects: An Exclusive Host National Context Produces More Perceived Discrimination among Immigrants. European Journal of Political Research 55 (2): 374-90.

---. 2017. Do They Belong? Host National Boundary Drawing and Immigrants' Identificational Integration. Aarhus: Politica.

---. 2018. What It Means to (Not) Belong: A Case Study of How Boundary Perceptions Affect Second-Generation Immigrants’ Attachments to the Nation. Sociological Forum 33 (1).

---. Forthcoming. The Democratic Consequences of Anti-Immigrant Elite Rhetoric: A Mixed Methods Study of Immigrants' Political Belonging. Political Behavior.

Skey, Michael. 2010. "A Sense of Where You Belong in the World:" National Belonging, Ontological Security, and the Status of the Ethnic Majority in England. Nations and Nationalism 16 (4): 715-33.

---. 2011. National Belonging and Everyday Life: The Significance of Nationhood in an Uncertain World. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

---. 2013. Why Do Nations Matter? The Struggle for Belonging and Security in an Uncertain World. The British Journal of Sociology 64 (1): 81-98.

Wimmer, Andreas. 2013. Ethnic Boundary Making: Institutions, Power, Networks. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wright, Matthew and Irene Bloemraad. 2012. Is There a Trade-off between Multiculturalism and Socio-Political Integration? Policy Regimes and Immigrant Incorporation in Comparative Perspective. Perspectives on Politics 10 (1): 77-95.