Potential into Practice: The Ethiopian Diaspora Volunteer Program

There is a growing recognition that diasporas make meaningful contributions to development efforts in their countries of origin through donations of their time, talents, and resources.

The work that diasporas carry out includes, among other things, channeling remittances to finance new businesses, increasing educational attainment for women and youth, and building roads and public-use buildings via infrastructure projects.

While diasporas frequently have the contacts, knowledge, and personal commitment to undertake these efforts alone, an emerging body of research and experience points to organized programs that mobilize the individual efforts of diasporas and, occasionally, coordinate their work to help meet the objectives of international agencies and developing country governments.

A powerful example of where diasporas, donors, and developing country governments have successfully collaborated is in public health capacity building, and particularly in dealing with the global HIV/AIDS epidemic. According to the United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS and the World Health Organization, two-thirds (or 22.4 million) of the 33.4 million people infected with HIV in 2008 lived in sub-Saharan Africa. By contrast, only about 3 percent of the world's health workers are in sub-Saharan Africa.

Diaspora volunteers have thus far played a small but important role in efforts to build healthcare capacity in developing countries, and the untapped potential for diaspora healthcare volunteers is likely substantial. About 1.4 million medical professionals in the United States are immigrants — more than one of every six medical professionals in the country. Of these, about 1.1 million (more than four out of every five) are from developing countries and over 120,000 (nearly one in ten) are from sub-Saharan Africa. These estimates, of course, exclude immigrants educated as medical professionals but who are either unemployed or work in a different field.

There is little doubt that these highly educated diasporas represent a substantial asset for efforts to improve healthcare and living standards in sub-Saharan Africa. However, a key challenge for development practitioners is to mobilize existing resources that are underutilized. In practice, mobilizing the latent expertise of diasporas requires that migration and development policymakers identify thoughtful strategies and implement targeted programs while retaining a proactive, if also critical, perspective on diasporas' interests and capacities.

This article reviews the experience of the Volunteer Healthcare Corps (VHC) — Ethiopian Diaspora Volunteer Program (EDVP), one innovative effort to mobilize diaspora volunteers to address healthcare capacity needs in their homeland. Specifically, the EDVP identifies, recruits, and places healthcare volunteers from the Ethiopian diaspora to build capacity in Ethiopia for the treatment of HIV/AIDS. Although small, the program has been successful in placing committed volunteers and can offer lessons for similar efforts elsewhere in the world.

Evolution of the Ethiopian Diaspora Volunteer Program

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the Ethiopian immigrant population in the United States has grown dramatically over the past three decades, from 7,516 in 1980 to 34,805 in 1990, and to 69,531 in 2000. As of 2008, there were 137,012 Ethiopian immigrants in the United States. In addition, about 30,000 native-born U.S. citizens claimed Ethiopian ancestry. Compared to other immigrants, Ethiopian-born immigrants aged 25 and older tend to be better educated, with 59.0 percent having had some college education or higher (compared with 43.5 percent among all immigrants).

But the Ethiopian diaspora extends well beyond the United States, with important Ethiopian diaspora communities residing in Australia, Canada, Germany, the United Kingdom, Nordic countries, and Israel, as well as throughout sub-Saharan Africa, North Africa, and the Middle East.

In recent years, reaching out to the diaspora and engaging them in Ethiopia's development has become an important priority for the Ethiopian government. A key challenge has been involving members of the diaspora who do not wish to return permanently to Ethiopia but who are still enthusiastic about contributing their time, skills, and energy.

Volunteer medical missions by diaspora professionals are a common mechanism for diaspora professionals to contribute to improving living standards in Ethiopia and helping the country progress toward the Millennium Development Goals. Experience suggests that these missions are a potentially powerful resource, but they often lack sustainability, broader impact, and coordination with other similar or related efforts.

Recognizing the potential for diaspora professionals to help the Ethiopian government address the country's pressing public health challenges, the U.S. government's Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Visions for Development, Inc. (Visions), and other Ethiopian diaspora community-based organizations convened 85 members of the Ethiopian diaspora in Atlanta in July 2005. The participants aimed to build a consensus for the creation of an Ethiopian diaspora network to support Ethiopia's AIDS prevention and treatment objectives.

They concluded that, among the many obstacles hindering greater diaspora involvement in addressing Ethiopia's AIDS challenges, the following were particularly important:

- A lack of information in Ethiopia and among international donors concerning the expertise of overseas Ethiopians and the availability of overseas Ethiopians to undertake volunteer work in Ethiopia;

- Geographic dispersion among the diaspora and a general lack of organizational structures or systems to match their skills with opportunities to assist in Ethiopia's HIV/AIDS campaign;

- An overreliance on informal methods of keeping in touch with current needs in Ethiopia, opportunities to assist, and points of contact;

- Discontent among some members of the diaspora concerning prior experience working in Ethiopia, and a lack of effective feedback and problem-solving mechanisms in Ethiopia;

- Inconsistency of terms and conditions for diaspora assignments due to the wide variety and lack of coordination among the initiatives of independent individuals and organizations.

Between February and May 2006, Visions conducted in-depth interviews to collect qualitative information from 38 selected health professionals such as physicians, nurses, epidemiologists, etc. The qualitative data collected revolved around the attitudes, perceptions, and experiences of Ethiopian diaspora health professionals in the United States and Canada toward volunteering.

The data collected indicated that the majority of the interviewees were interested in taking up a volunteer assignment in Ethiopia to address the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and that those interested had extensive experience treating HIV/AIDS in the United States. Additionally, nearly half had visited Ethiopia within the past five years, mostly to visit family and friends, with a median stay of about one month.

Most of the potential volunteers were motivated by a desire for personal satisfaction and for recognition of their acquired skills and expertise; assistance to their country of origin was considered a favorable outcome, but not a key motivation. In other words, the interest in volunteering was driven less by philanthropy and more by the emotional and social rewards they expected from volunteering.

However, the interviews also pointed to substantial barriers. While there is a general consensus that longer or repeat volunteer engagement is more valuable for the recipient communities, nearly two-thirds of the people surveyed indicated a preference for relatively short volunteer assignments of less than one month with a minimum of six months advance notice and lead time to prepare for the assignment.

When asked more narrowly about their reticence to undertake more protracted volunteer work, interviewees most often pointed to concerns about job and career responsibilities in the United States (90 percent) and family responsibilities (50 percent); a lack of awareness of volunteer opportunities was less commonly cited as a barrier (29 percent).

While the prospective participants acknowledged the need for financial and other support services in Ethiopia — as well as transportation — the lack of compensation was not a major barrier to volunteering. The most important factors cited as contributing to a decision to volunteer were the clear definition of a project that utilizes the volunteer's skills and experience, access to resources and support while in Ethiopia, and the provision of transportation costs to and from Ethiopia.

The EDVP grew out of these recommendations and findings. The EDVP facilitates the placement of volunteer professionals from the Ethiopian diaspora in specific sites that lack the human resources necessary to combat HIV/AIDS. The program is structured as a partnership among several groups that each bring unique talents to the venture.

- The American International Health Alliance (AIHA) is a nonprofit organization with experience placing volunteer health professionals in developing countries through its HIV/AIDS Twinning Center program, which is supported by the President's Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), a U.S. initiative that was first started in 2003 to combat the global AIDS epidemic.

- The Network of Ethiopian Professionals in the Diaspora (NEPID), the North American Health Professionals Association, People-to-People, Inc., and the Ethiopian Infectious Disease Network are professional associations with extensive contacts in the Ethiopian diaspora and medical professional communities.

- Finally, Visions is a nonprofit organization that coordinates the project with AIHA and the various professional and community groups.

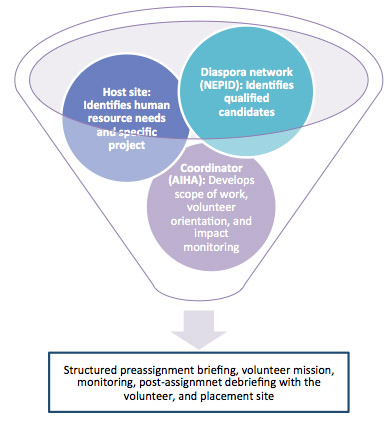

The Twinning Center office in Ethiopia identifies potential volunteer placements, surveys their specific human resource needs, and jointly develops scopes of work for each volunteer assignment (see Figure 1). Partnering community-based organizations and professional networks leverage existing networks among the diaspora to identify and recruit volunteers. In addition, volunteers are identified through an online portal and database maintained by NEPID.

Meanwhile, Visions assists in the matching and selection of volunteers, while the Twinning Center provides travel-related logistical support, orientation, monitoring, and ongoing assistance throughout the volunteer mission. AIHA provides volunteers with a monthly stipend to cover living and housing expenses.

|

|

||

|

The program has two principal objectives: to increase awareness among diaspora professionals of Ethiopia's national HIV/AIDS campaign and inform them of opportunities to become involved in volunteer assignments in Ethiopia, and to increase the diaspora's participation in Ethiopia's efforts to strengthen its health systems and build capacities by placing health professionals from the diaspora in volunteer positions at government institutions, hospitals, and HIV/AIDS service organizations in Ethiopia.

Between September 2006 and December 2010, the program placed 45 volunteers in over 30 sites. Placements included the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH), regional health bureaus throughout Ethiopia, local universities (particularly Addis Ababa University), the National AIDS Resource Center, Tikur Anbessa Hospital, and the University of Washington's International Training and Education Center for Health. These volunteers contributed a total of 552 months of volunteer time with an average volunteer assignment of around 12 months.

Volunteers performed a wide range of functions including developing pain treatment guidelines for the country's health professionals, building an online platform for the FMoH, performing outreach to foreign universities, refining and developing medical curricula for Ethiopia's teaching hospitals, and examining the country's anti-retroviral treatment program.

Guiding Principles and Lessons Learned

The guiding principles and lessons learned from the EDVP experience are drawn from questionnaire data collected from returned volunteers, site assessments and evaluations, exit debriefs with individual volunteers, focus group conversations with groups of volunteers, and insights from the program coordinators. Many are similar to good practices identified for other volunteer programs, while some are unique to diaspora volunteer programs.

1. Volunteers have diverse motives for undertaking a mission abroad.

Research points to at least six motivational factors that predict volunteerism: the opportunity to express values, a desire to improve understanding, to create or expand social networks, to advance career opportunities, to enhance ego and emotional wellbeing, and to support and assist a specific community.

In addition, personal factors and life circumstances have also proven to be highly relevant. For the individual volunteer, the literature suggests that ensuring a meaningful volunteer mission is central: volunteers must feel that they have developed substantive intrapersonal relationships and provided valuable services.

In the case of diaspora volunteers, all of these factors — in addition to personal engagements in the country of origin and, frequently, a desire to "pay back" — contribute to a high propensity and willingness to engage in volunteer work in their countries of origin. However, many volunteers also consider their engagement as a significant sacrifice requiring protracted absence from work and family life. On balance, the experience of EDVP suggests that volunteers from the Ethiopian diaspora — presumably similar to other diaspora volunteers — principally seek a meaningful personal experience rather than pecuniary rewards.

2. Individualized attention to the motivations of diaspora volunteers throughout the volunteer mission, from recruitment through return, leads to the selection of dedicated volunteers.

To address the individual needs and motivations of volunteers, and to ensure that the volunteer mission produced a meaningful experience, EDVP customizes work plans and volunteer missions. For instance, the EDVP designs volunteer opportunities specifically for academics on sabbatical, recent graduates, workers transitioning between jobs, and migrants exploring the idea of permanent repatriation to their country of origin.

This individualized attention, the program's coordinators believe, has led to an extraordinarily high retention rate. No volunteer has abandoned an ongoing mission: a rare feat for most volunteer programs in the developing world.

However, customization requires that the program invest substantial energy in interviewing and vetting prospective volunteers, as well as in identifying potential placement sites and developing detailed work plans for volunteers. Follow-up with the volunteers throughout their mission and for three to six months after their return is also required. This follow-up with volunteers — what the program's coordinators call case management — is considered a critical feature of the program, allowing coordinators to address challenges or issues as they arise rather than leaving problems to fester and lead to a negative experience for the volunteer.

3. Volunteer missions must meet the needs of both individual volunteers and the host sites to ensure sustainable impact.

Program coordinators — AIHA and Visions, in this case — must carefully balance the individual needs and motivations of volunteers with the human resource needs of host sites. The objective of the volunteer program is to build self-sustaining HIV/AIDS treatment capacity within Ethiopian health institutions. In this regard, the EDVP is designed as a tripartite partnership between the volunteers, the coordinators, and the host sites. The role of the coordinator is critical: not only as a placement service, but also to ensure that volunteers and hosts maximize the impact of the volunteer mission.

In the case of the EDVP, interviews were a crucial mechanism to understand the motivations and level of commitment of prospective volunteers and, the authors suspect, had enormous consequences for the success of volunteer missions. Equally, if not more important, has been the close collaboration and buy-in from Ethiopian government officials. By placing diaspora volunteers in policy development rather than just service-delivery positions — for example, as an advisor to the Ethiopian Health Minister — the program is able to influence local decision makers and is more likely to have a lasting impact.

|

In Their Own Words

|

||

|

4. The most effective recruitment and management strategies for diaspora volunteers rely on deeply rooted personal relationships within diaspora communities.

The experience of EDVP suggests that the most effective way to recruit and manage diaspora volunteers is through partnerships with individuals and organizations that maintain deep personal ties in diaspora communities. These individuals are typically familiar with the particular challenges and issues for each diaspora community, and their participation promotes ownership by the diasporas.

In some instances, embassies or consulates can also serve a similar function as intermediaries, although where the diaspora is politicized or where a diaspora has little confidence in the country of origin government, partnership with diplomats can be counterproductive.

5. Even diaspora volunteers require orientation and careful attention to managing expectations.

Diaspora volunteers return to a country that has often changed substantially from the country they left, and the volunteers themselves have also likely changed during their tenure abroad. Diasporas often assume the workplace culture of the societies where they reside, rather than the societies where they originate. Local workers, for their part, view diasporas ambivalently, sometimes recognizing their achievements while being skeptical of their expertise at other times.

Similarly, diaspora volunteers often harbor outsized expectations regarding the impact or conditions of the volunteer mission, particularly accommodation, the level of supervision, and transportation. Many have spent extended periods of time away from the country of origin, or are unfamiliar with working conditions in the developing world. There is typically a narrow window of opportunity during which a professional can volunteer, and programs face the constant risk of losing that energy or enthusiasm and generating cynicism.

Unfortunately, there is no simple solution to this conundrum beyond managing the expectations of volunteers and ensuring that they understand how their individual mission fits into a broader development strategy or diaspora engagement framework. This requires some degree of policy coordination and political buy-in. In the case of the EDVP, the initiative currently benefits from the support of Ethiopia's Health Minister and the United States' continued commitment to HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment in the developing world.

EDVP has addressed these challenges by providing forums for diaspora volunteers to interact with each other and with experienced volunteers. Opportunities to share their experiences with other volunteers can help alleviate the personal stresses of return to the country of origin, and deliberate efforts must be taken to create and sustain networks that allow volunteers to collaborate and provide peer-to-peer support. These efforts can include providing electronic mailing lists and organizing periodic meetings to connect current volunteers with returned volunteer mentors. Small efforts — such as providing volunteers with official identification — can have a substantial impact on volunteers' experiences.

6. Continuing to engage the volunteer after a mission ends is essential.

There is clear value in retaining contact with volunteers for subsequent longer-term placements. Once an assignment has finished and the diaspora volunteer returns to his or her country of residence, the benefits of the placement may diminish. Careful efforts must be made to build lasting connections between the volunteer and the placement site to ensure sustainability. Encouraging return volunteers, subsequent volunteer missions, and virtual relationships are all viable options to this end.

Conclusion

Though not the first program of its kind, the EDVP is a powerful example of where diasporas, international donors, and developing countries have collaborated to address global development challenges and meet common needs.

Other efforts that have worked to mobilize diaspora volunteers to address development challenges include programs managed by The United Nations Development Program, the International Organization for Migration, the UK's Department for International Development, Voluntary Service Overseas, and Canadian University Service Overseas.

The experience of the EDVP confirms the lessons of many of these earlier programs, especially those related to the recruitment, placement, and management of this rather unique category of volunteers. It also faces many of the same challenges of these earlier diaspora volunteer programs, including those associated with scale and sustainability. As with all diaspora volunteer programs, coordinating the activities of donors, developing countries, diaspora groups, and volunteers requires deft administration.

In spite of these challenges, the potential of diaspora volunteers to help international and national development agencies meet the Millennium Development Goals is undeniable. Substantial volunteer activity is already underway via informal links and person-to-person contacts. However, greater coordination and cooperation among the various actors would likely improve these impacts and outcomes. Similar to other volunteer efforts, diaspora volunteers are an important tool among many others in the development policy arsenal.

This article was adapted from the report "Mobilizing Diaspora Volunteers for Public Health Capacity Building: Lessons Learned from the Ethiopian Diaspora Volunteer Program" by Tedla W. Giorgis and Aaron Terrazas and published by Visions for Development, Inc.

Sources

Batalova, Jeanne and Michael Fix with Peter A. Creticos. 2008. Uneven Progress: The Employment Pathways of Skilled Immigrants in the United States. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available Online.

Gilbert, Elon et al. 2005. Managing International Volunteer Programs: A Farmer-to-Farmer Manual. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development.

Newland, Kathleen, ed. 2010. Diasporas: The New Partners in Global Development Policy. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development and Migration Policy Institute.

Office of the United States Global AIDS Coordinator. 2009. Celebrating Life: The U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, 2009 Annual Report to Congress. Washington, DC. Available Online.

Office of the United States Global AIDS Coordinator. 2009. The U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief: Five-Year Strategy. Washington, DC. Available Online.

Terrazas, Aaron. 2010. Connected through Service: Diaspora Volunteers and Global Development. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development and the Migration Policy Institute. Available Online.

United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and World Health Organization (WHO). 2009. 2009 AIDS Epidemic Update. Geneva. Available Online.

USAID Development Information Service. 2003. The Value of International Volunteerism: A Review of Literature on International Volunteer-Sending Programs. Washington, DC.

World Health Organization. 2008. Task Shifting: Rational Redistribution of Tasks among Health Workforce Teams, Global Recommendations and Guidelines. Geneva. Available Online.