You are here

Redefining Nepal: Internal Migration in a Post-Conflict, Post-Disaster Society

Hundreds of thousands in Nepal were left homeless after devastating 2015 earthquakes, while internal migration continues to complicate aid delivery and political reforms. (Photo: Shukuko Koyama/ILO)

Until disaster struck on April 25, 2015, Nepal was most famed among travelers for its staggering beauty, and within policy circles for an explosion in the export of labor, with Nepalis working abroad having quickly become essential to the country’s economic, political, and social stability.

These migrant workers and others in the Nepali diaspora now provide nearly 29 percent of Nepal’s gross domestic product (GDP) in the form of international remittances, and in some districts more than half of households rely on these receipts from abroad to supplement local incomes. As Nepal seeks to rebuild after devastating earthquakes in April and May that claimed more than 8,700 lives and injured countless more, left hundreds of thousands homeless, and dealt a blow to its vital tourism industry, the population’s dependence on remittances will become even more acute. And if the habits of the Nepali diaspora mirror those of other expatriate communities whose countries have faced devastation, Nepali households will benefit from a surge in money sent to help rebuild lost homes and fill the spending gaps left by shattered domestic livelihoods.

Nepal can turn to an ever-larger migrant workforce. In 2014, more than half a million Nepalis, the vast majority lesser educated young men, exited the country for work in the labor-hungry economies of Asia and the Middle East. Up to 1.5 million others in the country of 27.8 million are estimated to regularly cross Nepal’s long, porous border for permit-free work in India. To give a sense of scale of the changes, one in ten households had a member living abroad in 2001. A decade later, the rate was one in four—a dramatic pace of change over a short period of time fueled by a mixture of factors including poverty, civil war, and government efforts to remove obstacles to emigration.

As important as international migration is to Nepal’s present and future, it is only one aspect of the patterns of mobility and change that have occurred in the country—and that undoubtedly have been scrambled by the earthquakes that devastated parts of Kathmandu and other districts on the sending and receiving end of high numbers of internal migrants.

Internal migration has long played a significant role in Nepali society. From the journeys of nomadic tribes and soldiers, to those propelled by environmental and economic change, migration within Nepal remains interwoven with issues of ethnicity, social mobility, and political representation. From 2010 to 2015, Nepal experienced one of the highest rates of urbanization in the world, though it still has one of the region’s least urban populations. The country also is seeing an increasing feminization of its workforce, as women fill gaps left by absent males or themselves migrate—internally and abroad—to access opportunity.

This article examines three internal migration trends that are redefining a post-conflict, post-disaster society, before delving into the roots of Nepali migration and the overlooked role of internal movement in the struggle to create a new constitution.

Internal Migration Trends

Nepal is divided into three ecological zones stretched from east to west. The Himalayan mountain range constitutes the northern-most belt. In the south, the hot and humid plains—known as the terai—comprise fertile lands and vast forests, for a long time sparsely populated and largely uncultivated. Sprawling across the central belt is the hill region—pahar—which makes up the bulk of Nepali landmass, but no longer the majority of its population.

Five administrative development regions cut vertical north-south slices through the ecological zones and are locked in by the borders of India and China. They are named geographically, from the Far Western to the Eastern.

Figure 1. Ecological Zones and Development Regions of Nepal | |

Source: Elisa Muzzini and Gabriela Aparicio, Urban Growth and Spatial Transition in Nepal: An Initial Assessment (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2013), http://issuu.com/world.bank.publications/docs/9780821396599. |

Migration between ecological belts and development regions is well captured by census and survey data, and reveals some interesting trends. The most visible is the exodus of the economically active population from the hills and mountains to the Kathmandu Valley and the terai, leaving some earthquake-ravaged villages with too few hands to even move the rubble.

Those leaving their homes come from across the social spectrum, but the richest (with the exception of relatively small flows of international students and other elites) and the very poorest economic migrants and their families tend to remain within Nepal: the former often more able to purchase land or secure the most coveted jobs in government, business, and civil society, and the latter pursuing low-wage work in neighboring districts.

From the Hills to the Plains

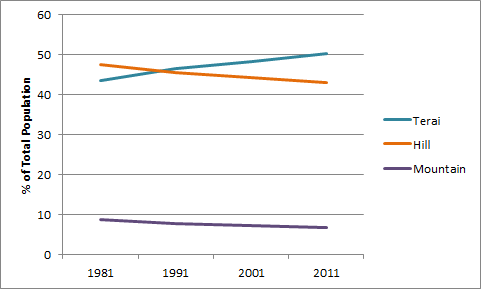

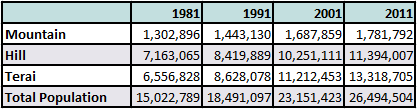

Within Nepal, at least 15 percent of the population resides outside of the district of birth. Three-quarters of these migrants come from the pahar (hills) and mountain regions, with some districts seeing an exodus of more than 50 percent of their population. Those who do not head abroad mostly go to the terai. Once a region of virgin forests and rampant malaria, the terai is now home to the country’s fastest-growing population, despite fertility rates that are persistently lower than for districts in the hills and mountains. Since the 1980s, the terai has hosted the largest population (in absolute and proportional terms), concentrated mainly in the Central and Eastern development regions.

Figure 2. Nepali Population Share by Ecological Zone, 1981-2011 | |

Source: Nepal Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), National Population and Housing Census 2011 (Tables from Form-II) Vol. 3 (Kathmandu: CBS, 2014), http://cbs.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/NPHC2011%20%28Tables%20from%20Form-II%29.pdf. |

Flows to the terai have been mixed. Originally driven by high-caste Hindus resettled in the 1950s under special schemes designed to relieve land pressures in the hill region and compensate flood-affected farmers, many among lower castes and other minority groups—whose lack of land in the first place usually made compensation a somewhat redundant concept—have migrated in a more ad hoc fashion. In many cases, migrants dispatched by their families would leave a village to seek suitable opportunities in and around the formal settlements of government grantees. They were eventually followed by fellow villagers, who formed clustered settlements at destination in a practice of highly localized chain migration. Many of those already resident in the terai who could not compete with the wealth and power of the new arrivals have been displaced westwards, or forced to work on deeply unfavorable terms.

Table 1. Total Nepali Population by Ecological Zone, 1981-2011 | |

Source: CBS, National Population and Housing Census 2011 (Tables from Form-II) Vol. 3. |

Urbanization Gathers Speed

Nepal’s urban population—currently relatively low at 17 percent—is rapidly increasing, with its cities growing between 4 and 7 percent per year. Yet life remains overwhelmingly rural, with more than 60 percent of the population making a living directly from agriculture, and rural-to-rural migration remaining dominant.

In some ways, however, the rural-urban dichotomy favored by policymakers may be misleading. Migrants often circulate in a seasonal pattern, rotating work on the land with employment in towns, while households are often stretched between the migrant’s place of work and the rural base at which family and property remain.

This pattern also plays out across international boundaries. For many of those in the Western and Far Western regions, Indian border towns and larger cities—such as New Delhi—often offer better opportunities for employment than are accessible in Nepal. The porous border facilitates a similar circular migration, and for those who settle, a cross-border urbanization frequently overlooked in country-level analyses.

Migration and Social Mobility

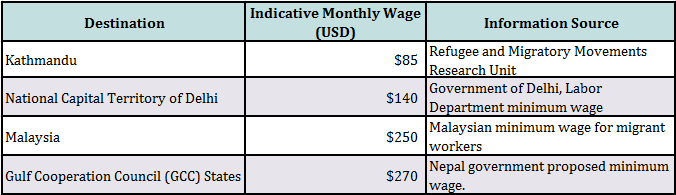

Data on which kind of migrants head to various destinations is limited by the questions posed by the census of families with “absent members,” and to independent case studies and small-scale surveys. Lower-income families tend to send workers to India, where migrants can easily cross the border and find wages higher than at home. As wealth rises to the levels necessary to finance high recruitment agency fees, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries and Malaysia become the destinations of choice where, wages, though hugely variable, are generally much higher (see Table 2). Yet Nepalis are aware of the risks that come with foreign placements at the hands of often unscrupulous employment agents and insecure labor rights, so although workers in a wide income band sign labor contracts abroad, those with more skills and wider networks—typically the higher-income percentiles—are more likely to look for internal opportunities, often in the two biggest cities of Kathmandu (in the Central hill region) and Pokhara (in the Western hills), than emigrate on unfavorable terms.

Table 2. Potential Earnings of Low-Income Nepali Migrants, Select Destinations | |

Notes: Exchange rate as of May 2015. Work is often informal, minimum wages are often flouted, and wages not paid; conversely, workers may be able to supplement earnings with overtime work or employer-provided in-kind contributions such as food and accommodation, the rates of which are not considered here. The amounts given are therefore indicative of differing potential earnings that may motivate migration decisions, but are not an authoritative guide to actual income. Sources: Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit (RMMRU), “Internal Migrant Construction Workers in Nepal: Tackling Exploitative Labour Practices to Enhance Migration’s Impact on Poverty Reduction” (Policy Brief 12, RMMRU, Dhaka, Bangladesh, December 2014), http://migratingoutofpoverty.dfid.gov.uk/files/file.php?name=rmmru-rp002-nepal-policy-brief-12-nepal-sep14.pdf&site=354; Ashok Thapa, “Govt officially endorses workers’ minimum salary of Rs 8,000,” The Kathmandu Post, June 12, 2013, www.ekantipur.com/the-kathmandu-post/2013/06/12/money/govt-officially-endorses-workers-minimum-salary-of-rs-8000/249919.html; Government of Delhi, Labor Department, “Current Minimum Wage Rate,” updated May 31, 2015, www.delhi.gov.in/wps/wcm/connect/doit_labour/Labour/Home/Minimum+Wages/; Roshan Sedhai, “Overworked and Underpaid,” eKantipur.com, December 4, 2014, www.ekantipur.com/2014/12/04/capital/overworked-and-underpaid/398530.html; Peter Kovessy, “Report: Nepal Pushes for Higher Minimum Wage for its Workers in Qatar,” Doha News, January 22, 2015, http://dohanews.co/report-nepal-pushes-higher-minimum-wage-workers-qatar/. |

In a distinctly unequal society built on a part-caste, part-ethnic hierarchical system made illegal only in 1962, ethnicity and caste often serve as fairly reliable proxies for class and wealth. The desirable jobs in the civil service, army, and judiciary, for instance, are overwhelmingly dominated by high-caste Hindu pahadi. At the other end of the spectrum, some minority ethnic groups have remained largely outside the cash economy and a few have not moved beyond traditional agricultural or hunter-gatherer livelihoods. The indigenous—or janajati—groups that have been absorbed into the mainstream economy still find themselves on the margins, and supported labor market integration and antidiscrimination measures have long been on the agenda of the Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities (NEFIN), the umbrella group representing their interests nationally.

Among other factors, migration has put this system under severe strain. As migrants from rural areas are exposed to new places and skills, as well as different ways of doing things, they accumulate knowledge and skills beyond the agricultural expertise handed down by their relatives. These migrants adjust their future expectations accordingly, as do other young Nepalis who see them return following a successful sojourn.

Returning international migrants often use their skills and newfound networks to access opportunities in Nepal’s cities, suggesting that international migration may be a catalyst for internal social mobility, according to research by the Overseas Development Institute. This has occurred amid an unprecedented rise in urban youth unemployment and caused significant consternation among policymakers, who must contend with a mismatch between abundant labor in urban areas and acute shortages in the countryside.

Gender Dynamics

Remittances—social and financial—have also had an effect, with new money and ideas changing the way people in rural areas envisage their lifestyles and positions in society. Nowhere is this more apparent than in rapidly changing gender dynamics. While men continue to dominate international flows (though rising numbers of Nepali women are emigrating), internal migration flows are increasingly feminized; in 2011, for every 100 women moving from one ecological zone to another (for example, hills to terai), there were just 84 men doing the same. A decade earlier, there was near parity. Where women once overwhelmingly moved for marriage, labor market activity is becoming increasingly important. The absence of men in villages—especially when remittances are not forthcoming—mean more women are taking on the breadwinning role, performing both housekeeping and agricultural tasks, or themselves migrating for work.

The role of rural women in combat has further undermined the traditional patriarchal values of the joint Hindu family, a practice of communal living that was for centuries central to Nepal's national sense of self. During the civil war from 1996 to 2006, women comprised 20 percent to 40 percent of the Maoist People’s Liberation Army, the militant wing of the Unified Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist), which sought to overthrow the Nepalese monarchy in favor of a People’s Republic. A high proportion of women in the opposition forces held high-ranking combat positions, senior posts from which they have been largely excluded in their proposed post-conflict integration into the Nepalese Army. Returning to subservient gender roles after a decade of mobility and power has been anathema to many, and may explain in part their increased propensity to migrate for alternative opportunities.

International migration is more complicated for Nepali women, with the government variously imposing and retracting restrictions on their recruitment in hopes of protecting women from abuse. Restrictions have been toughest on women applying for permits to work in GCC countries, though other destinations also require strict consular oversight. Despite various bans and restrictions, the acquisition of permits has risen—by 239 percent over the past six years—and arguably because of the ban, irregular migration has also increased, mostly via illicit agents based in India. Most recently, the Nepali government has taken steps to restart the flow of workers, including lifting the moratorium on female workers going to GCC countries and lowering the minimum age requirement from 30 to 24, though other strict conditions still apply. As well as acknowledging women’s right to migrate for work legally, the move follows a strong economic logic: women who do move, abroad and within Nepal, tend to both earn and remit more than their male counterparts.

Causes of Migration

Nepal’s population has been mobile throughout its history. Since long before the formation of the modern Nepali nation-state, the practice of transhumance has seen farmers and their livestock migrate seasonally in search of greener pastures. Later, migration was driven by government policy, as the ambitious but cash-strapped Shah family, which founded the first modern Kingdom of Nepal in the mid-18th century, coerced the lower classes into working and fighting all over the country for little or no remuneration. The peasant classes also found migration to be an effective means to escape abusive overlords in an oppressive feudal system. Mass recruitment into the East India Company’s Gurkha regiments in the 19th century and later for the British then Indian armies perpetuated a strong link between the military and mobility. In more recent times, that dynamic has extended and shifted as nearly 200,000 people were displaced as a direct result of the civil war. Approximately 50,000 people remained internally displaced by armed conflict as of February 2015, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. Many remain in the terai, mainly due to a continuing sense of insecurity and unresolved property issues following the appropriation and redistribution of land in Maoist strongholds in the Western and Far Western hills.

The livelihoods of a majority of Nepal’s inhabitants are directly dependent on agriculture. Climate change, population growth, landlessness, and soil degradation together may undermine the sustainability of sustenance farming, and the massive earthquakes of April and May 2015 may well compound existing challenges. Survival is hardest for those with the smallest landholdings, but relative wealth is little protection in the face of changes to Nepal’s delicately balanced subclimates, with agriculture threatened by floods, landslides, and drought. The United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has found that 6.9 million people in Nepal live with chronic food insecurity, meaning cash income is essential to survival for many. With alternative forms of local employment scarce, villagers must go to the money.

The earthquakes’ immediate effects on internal migration, as many Nepalis headed to home villages either to flee devastation or check in on the well-being of loved ones, was captured in a striking example. Flowminder, a Swedish nongovernmental organization, used mobile phone data to document internal movement in the weeks immediately after the April earthquake. Using anonymized phone records of national telecommunications provider NCell, Flowminder reported a 5 percent drop in the population of Kathmandu, which is a major migrant destination, and a 5 to 11 percent increase in the population of some of the worst-affected districts in the surrounding area.

Many of the districts most affected by the earthquakes were also the most connected to internal migration flows before the disaster. Reduced economic activity amid the wreckage of top migrant-receiving destinations such as Kathmandu, Lalitpur, and Bhaktapur will likely have an adverse effect on internal remittance flows and spending power in top migrant-sending districts, especially those that have also been badly affected by the earthquake, such as Gorkha, Sindhulpachok, and Dhading. In contrast, none of the earthquake-affected districts have so far topped the list of those sending migrants abroad: the relatively high level of local employment and higher wages enabled residents and internal migrants to support families without the need to seek opportunities overseas. In the immediate aftermath of the earthquakes, international migration has slowed and many from abroad have returned. It remains to be seen, however, whether this major setback to Nepal’s economic development will spur higher levels of international migration in the longer term.

Towards a Mobile Future

Nepal is pursuing a new constitution that will eventually birth an eight-state federal republic, nine years after the Comprehensive Peace Agreement ended the civil war and brought the Maoists into mainstream politics. Extensive negotiations between members of the Constituent Assembly—the body tasked with drafting a new constitution—produced little, but with their bickering and paralysis thrown into an unflattering, global spotlight in the aftermath of the earthquakes, politicians have been pressured into action, signing a deal on June 8 that will pave the way for a new constitution.

For a long time, a myth of national homogeneity pervaded Nepal, where elites built policy on the notion that ethnic, social, caste, and class differences did not exist, or were secondary to a common sense of national identity. Far from mitigating the underlying tensions of a deeply unequal society, attempts to sweep differences aside resulted in civil war. Now, civil unrest, strikes, protests, and sabotage characterize the contest over the country’s future amid ever higher mobility and in the aftermath of tragedy and disaster.

At the heart of the constitutional debate has been the structure of the new federal state, and disputes over whether states should be delineated based on ethnic-group self-determination interests or on economic feasibility. Even as the debate has broken along ethnic group lines, internal migration flows have rearranged the population in such a way that in a country that was once home to hundreds of dispersed tribes whose distinctiveness grew through their isolation, only 15 of 75 districts can now claim to have an absolute majority of any one ethnic group.

The deal in the Constituent Assembly reached on June 8 in some ways sidesteps the dispute between the madhesi, pahadi, and janajati, among myriad other interested parties, leaving the names and boundaries of federal states in the charge of future provincial councils and the State Restructuring Commission, respectively.

To further complicate political reforms, the earthquakes have displaced hundreds of thousands of people, and the challenge of tracking large-scale, multidirectional internal movements—of the displaced, returning family members, and new internal economic migrants—can make it difficult to allocate aid and plan effectively for the longer term.

The arrival of the monsoon season just a few months after the earthquakes underscores the urgency with which policymakers must understand and respond to an emergency situation on the ground without losing sight of the longer-term factors driving change in Nepal. The need for post-disaster reconstruction comes in the midst of a nation rebuilding itself—a process in which migrants, internal and international, will remain essential.

Sources

Aalen, Lovise and Magnus Hatlebakk. 2008. Ethnic and Fiscal Federalism in Nepal. Bergen, Norway: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI). Available Online.

Ariño, Maria Villelas. 2008. Nepal: A Gender View of the Armed Conflict and Peace Process. Barcelona: School for a Culture of Peace. Available Online.

Banerjee, Soumyadeep, Richard Black, Dominic Kniveton, and Michael Kollmair. 2014. The Changing Hindu-Kush Himalayas: Environmental Change and Migration. In People on the Move in a Changing Climate: The Regional Impact of Environmental Change on Migration, eds. Etienne Piguet and Frank Laczko. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer, 2014.

Bhattachan, Krishna. 2000. Possible Ethnic Revolution or Insurgency in a Predatory Unitary Hindu State, Nepal. In Domestic Conflict and Crisis of Governability in Nepal, ed. Dhruba Kumar, Kathmandu: Center for Nepal and Asian Studies.

Flowminder Nepal Population Estimates. 2015. Created May 29, 2015. Accessed June 2, 2015. Available Online.

Gardner, Andrew, Silvia Pessoa, Abdoulaye Diop, Kalthan al-Ghanim, Kien Le Trung, and Laura Harkness. 2013. A Portrait of Low-Income Migrants in Contemporary Qatar. Journal of Arabian Studies 3 no.1 (2013): 1-17.

Government of Delhi, Labor Department. 2015. Current Minimum Wage Rate. Updated May 31, 2015. Available Online.

Hagen-Zanker, Jessica. 2015. Risking Everything: Vulnerabilities and Opportunities in Migration. Public lecture, Overseas Development Institute, London, February 6, 2015. Available Online.

Hagen-Zanker, Jessica, Richard Mallett, Anita Ghimire, Qasim Ali Shah, Bishnu Upreti, and Haider Abbas. 2014. Migration from the Margins: Mobility, Vulnerability, and Inevitability in Mid-Western Nepal and North-Western Pakistan. London: Overseas Development Institute, October 2014. Available Online.

Himalayan News Service. Report: Government Gearing Up to Send Domestic Workers as Help. The Himalayan Times, June 16, 2015. Available Online.

Institute of Development Studies. 2014. Rapidly Urbanising Nepal and Youth Unemployment Present Challenges to Security Provision. News release, August 18, 2014. Available Online.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Center. N.d. Nepal IDP Figures Analysis. Accessed June 8, 2015. Available Online.

Kovessy, Peter. 2015. Report: Nepal Pushes for Higher Minimum Wage for its Workers in Qatar. Doha News, January 22, 2015. Available Online.

Mohapatra, Sanket, George Joseph, and Dilip Ratha. 2009. Remittances and Natural Disasters: Ex-Post Reponse and Contribution to Ex-Ante Preparedness. Policy Research Working Paper 4972, The World Bank, Washington, DC, June 2009. Available Online.

Muzzini, Elisa and Gabriela Aparicio. 2013. Urban Growth and Spatial Transition in Nepal: An Initial Assessment. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Available Online.

Nepal Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). N.d. National Report 2001. Kathmandu: CBS. Available Online.

---. 2012. National Population and Housing Census 2011 (National Report), Vol. 1. Kathmandu: CBS. Available Online.

---. 2014. National Population and Housing Census 2011 (Tables from Form-II), Vol. 3. Kathmandu: CBS. Available Online.

---. 2014. Population Monograph of Nepal Volume I (Population Dynamics). Kathmandu: CBS. Available Online.

---. 2014. Population Monograph of Nepal Volume II (Social Demography). Kathmandu: CBS. Available Online.

Nepal Ministry of Labor and Employment. 2014. Labour Migration for Employment: A Status Report for Nepal 2013/14. Kathmandu: Ministry of Labor and Employment. Available Online.

Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project. 2004. Profile of Internal Displacement: Nepal. Geneva: Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project. Available Online.

Poertner, Ephraim, Mathias Junginger, and Ulrike Müller-Böker. 2011. Migration in Far West Nepal. Critical Asian Studies 43 (2011): 23-47.

Pravat, Poshendra Satyal and David Humphreys. Using a Multilevel Approach to Analyse the Case of Forest Conflicts in the Terai, Nepal. Forest Policy and Economics 33 (2013): 47-55.

Rai, Om Astha. 2015. Constitution Deal Inked. Nepali Times, June 8, 2015. Available Online.

---. 2015. Migrants Inbound. Nepali Times, May 21, 2015. Available Online.

Ratha, Dilip. 2013. The Impact of Remittances on Economic Growth and Poverty Reduction. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available Online.

Refugee and Migratory Movements Research Unit (RMMRU). 2014. Internal Migrant Construction Workers in Nepal: Tackling Exploitative Labour Practices to Enhance Migration’s Impact on Poverty Reduction. Policy Brief 12, RMMRU, Dhaka, Bangladesh, December 2014. Available Online.

Sedhai, Roshan. 2014. Overworked and Underpaid. eKantipur.com, December 4, 2014. Available Online.

Shreshta, Nanda R. 2001. The Political Economy of Land, Landlessness and Migration in Nepal. Kathmandu: Nirala Publications.

Suwal, Bhim Raj. 2014. Internal Migration in Nepal. Population Monograph of Nepal Volume 1 (Population Dynamics). Kathmandu: CBS. Available Online.

Thapa, Ashok. 2013. Govt Officially Endorses Workers’ Minimum Salary of Rs 8,000. The Kathmandu Post, June 12, 2013. Available Online.

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). 2015. Nepal: Earthquake 2015 Situation Report No. 20. Kathmandu: OCHA. Available Online.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (ESA). 2014. World Urbanization Prospects, Highlights. New York: UN ESA. Available Online.

World Bank Prospects Group. 2011. Large-Scale Migration and Remittance in Nepal: Issues, Challenges, and Opportunities. Washington, DC: The World Bank. Available Online.

---. 2015. Personal Remittances, Received (% GDP). Available Online.

World Food Program. 2009. Winter Drought Worsens Food Insecurity in Nepal. News release, May 31, 2009. Available Online.