You are here

Refugee Flows to Lesvos: Evolution of a Humanitarian Response

Conditions at Kara Tepe camp in Lesvos, Greece deteriorated as arrivals quickly overwhelmed capacity. (Photo: Joel Hernandez)

The Greek island of Lesvos, separated from Turkey’s coastline by a thin sliver of the Aegean Sea, is no stranger to refugee flows. In the aftermath of the 1919-22 Greco-Turkish War, thousands of Anatolian Greeks forcibly displaced from Turkey found safety and started new lives in Lesvos. Almost a century later, the island’s local population of approximately 85,000 played host to more than half a million migrants and asylum seekers from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, and beyond over the course of 2015. This figure represents about 59 percent of all asylum seekers and migrants who transited through Greece in 2015 en route to preferred asylum destinations in northern Europe.

A major focal point in the migration flows that brought more than 1 million asylum seekers to Europe in 2015 alone, Lesvos offers an invaluable case study in the promises, pitfalls, and progress in the West’s humanitarian response to the ongoing refugee crisis. From landing beaches staffed mainly by volunteers to the registration centers and transit camps run by professional aid organizations, the needs and pressures visited upon both asylum seekers and responders in Lesvos bear significant lessons for aid providers and policymakers along the onward migration routes in the Balkans and across Central Europe. Based on interviews with aid workers, journalists, and volunteers, as well as the author’s experience volunteering with asylum seekers in Lesvos for several months in 2015, this article examines the logistical, labor, and coordination challenges that are complicating the humanitarian response on the island.

Northern Lesvos: An Ad Hoc Volunteer Response

Though Lesvos is visible from Turkish shores, the crossing typically takes about two hours on the rubber dinghies most commonly used by smugglers—assuming the vessel was supplied with sufficient gasoline, its engine does not fail, waters are calm (a rarity in the winter), and the Turkish coast guard does not intercept at sea. The most prominent landing beaches, on Lesvos’ northern shore, lie adjacent to an eight-mile, largely unpaved road that links the small towns of Molyvos and Skala Sikamineas. Over the summer of 2015, as the European Union struggled to find consensus and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) drew up response plans, asylum seekers were most often greeted by locals and tourists who volunteered to shepherd and care for them. Volunteer-organized convoys drove women, children, and the elderly to transit centers in Molyvos or Skala Sikamineas, while able-bodied men—the majority of arrivals—were left to walk into town. Asylum seekers rescued by the Greek Coast Guard were taken directly to the Molyvos harbor. From there, most were forced to walk the 65 miles to Mytilene where they could catch a ferry to the mainland, as Greece’s anti-human trafficking laws prevent taxis and commercial buses from transporting them. (Greece altered the law in July to allow private individuals to drive asylum seekers.)

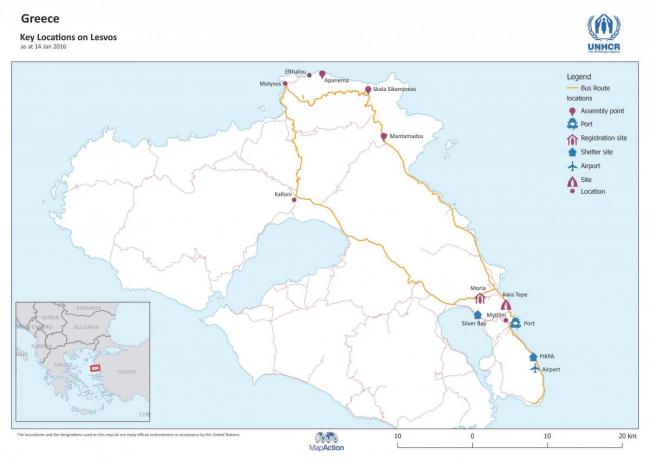

Figure 1. Key Locations on Lesvos for Asylum Seekers

Source: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and MapAction, “Greece: Key Locations on Lesvos,” January 14, 2016, available online.

While traditional aid organizations such as the International Rescue Committee (IRC) were present on the southern part of the island, until December 2015 few were active in the north, where the vast majority of asylum seekers and migrants make landfall. The humanitarian response there was initially left to volunteers and local residents, led by Eric and Philippa Kempson, long-time British expatriates, and Melinda McRostie, a Greek-Australian restaurant owner. Their ad hoc efforts sought to address the immediate needs of those arriving. Long accustomed to providing water, food, other goods, and basic guidance to the occasional boatload of arriving migrants in years past, the Kempsons ramped up their aid distribution and became full-time volunteer coordinators as migrant arrivals surged dramatically in spring and summer 2015. Their daily video updates opened a window to the migration crisis long before reporters or advocates began converging on the island. McRostie built a volunteer organization around the Captain’s Table, her restaurant in the Molyvos harbor, and used donations to feed and clothe asylum seekers by the thousands over the summer of 2015. Dozens of volunteers of all ages and origins flocked to Molyvos to shuttle asylum seekers in rental cars, and to distribute food, water, dry clothes, and toys. Despite the generosity, it quickly became clear that without the support of established humanitarian aid organizations and greater infrastructure, their efforts could not but fall short of meeting the needs of the growing numbers of asylum seekers.

Filling the Gaps

The volunteer-led response of July and August 2015 formalized steadily over the subsequent fall. A number of volunteers began establishing organizations to better fund-raise, recruit more volunteers, and build credibility in order to provide a more comprehensive humanitarian response. McRostie and Emma Eggink, a recent graduate, launched the Starfish Foundation (Asterias in Greek) to address transportation and other basic needs, helping to move thousands of asylum seekers from the beach to a reception camp established in the parking lot of the Oxy nightclub near Molyvos. The foundation devised ticketing systems for food and transportation to effectively manage the transit camp. Dozens of long-term volunteers distributed food, water, clothes, and information booklets in Arabic and Farsi. On its busiest day, approximately 6,000 people passed through the camp in a single 24-hour period in late October. With buses financed by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Médecins sans Frontières (MSF), and the IRC, Starfish Foundation coordinated transportation from the Oxy camp to Mytilene. Though the Oxy camp was replaced in late December 2015 with a camp at Apanemo run by the IRC, Starfish Foundation remains active distributing food and other items in northern Lesvos and is establishing operations at the Moria transit camp.

The Dutch Stichting Bootvluchteling (the Boat Refugee Foundation) grew from a limited operation deploying two volunteers at a time over the summer to a comprehensive rescue-and-relief operation. The foundation now fields a dozen rotating volunteers (including a medical professional) who operate a fleet of several cars, a minibus, and a rescue boat. Under the coordination of Manon Terpstra, who first came to Lesvos as a volunteer in the summer, Stichting Bootvluchteling volunteers patrol the coastal roads, monitoring the waters between Turkey and Lesvos with high-powered binoculars and signaling the location of boats to counterparts on sea patrol. While the seaborne volunteers guide boats toward designated beaches, land-based teams help asylum seekers onto dry land, issue emergency blankets, and provide first aid and transportation to the Apanemo camp.

Further assistance in maritime rescue is provided by a nonprofit led by Oscar Camps, a professional lifeguard moved to action by the photo of Alan Kurdi, the three-year-old Syrian boy whose body washed ashore. Camps relocated to Lesvos in September and launched ProActiva OpenArms, a nonprofit extension of his Barcelona-based lifeguard company. ProActiva OpenArms supports two fully equipped rescue boats and a team of several dozen rescuers who are available around the clock to guide asylum seeker boats toward designated reception beaches where volunteers are ready to provide first aid, tow those whose engines have stopped, and rescue migrants who have jumped out of boats or fallen into the water. Their efforts have saved dozens of asylum seekers from drowning following shipwrecks off Lesvos. MSF Sea, the Norwegian Drop in the Ocean Foundation, the Greek Red Cross, Islamic Relief, and Greenpeace, as well as varying numbers of unaffiliated volunteers, have also contributed to maritime and land-based rescue efforts on Lesvos’ northern coast.

Professionalization of Operations

In December 2015, the IRC expanded to the northern shores of Lesvos after a longtime presence in transit camps near Mytilene, establishing and operating the Apanemo camp. This action completed the transition of the northern Lesvos theater from an ad hoc, volunteer-led response to an official, professional operation by a major organization in the humanitarian space. Several minibuses provide transport to Apanemo for newly arriving asylum seekers, and from there to a bus stop in Efthalou for transport to the transit camps near Mytilene. Though reaching Lesvos remains a dangerous and taxing endeavor for asylum seekers, those attempting the journey in 2016 will encounter a comprehensive, properly funded, and resilient humanitarian operation upon arrival. While increasingly robust volunteer groups continue to play an important role, the organization and infrastructure provided by international NGOs such as the IRC have resulted in greater capacity to more effectively address the needs of the thousands of asylum seekers and migrants who continue to arrive in northern Lesvos.

Mytilene: Official Response Center and European “Hotspot”

Mytilene and the nearby transit camps of Kara Tepe and Moria serve as the nerve center of the official Greek and European response, and in October 2015 were designated EU “hotspots,” as a result gaining significant new resources to identify and register asylum claims. Moria, a small village northwest of Mytilene, hosts a prescreening center where asylum seekers’ origins are determined by personnel from the EU border agency Frontex. Syrian nationals are sent to Kara Tepe, where they register with Greek authorities, have their fingerprints recorded, and, after waiting one to two days, receive transit papers allowing them to remain in Greece for up to six months. Other nationals remain at the hotspot in Moria, where the same process usually takes about a week.

Improving Conditions at Kara Tepe

The municipality of Mytilene established the Kara Tepe camp on a hilltop north of town, on the site of an olive grove and adjacent motorcycle training course. Though the IRC, Médecins du Monde, and MSF have been present in Kara Tepe since June 2015, there were only about a dozen full-time humanitarian personnel in the camp during the summer. Greek police and Coast Guard officers also made regular visits to the camp, helping maintain order and handing out transit papers to registered asylum seekers. However, the numbers of arriving asylum seekers quickly overwhelmed the camp’s capacity and the ability of responders to maintain sanitary conditions. In a mid-July assessment, Save the Children observed camp dwellers “sleeping rough, some on soiled mattresses, others on battered mats, and others on nothing at all.” Another observer, French military officer-turned-humanitarian Fred Morlet, who has been in Lesvos since July 2015, described the humanitarian situation in Kara Tepe in a mid-August report as “catastrophic”: the edges of the camps, used as garbage dumps, attracted flies and rats; water pressure was insufficient for toilets to properly flush; lighting and electrical supply were intermittent and unsafe, causing recurring electrical fires; and camp dwellers slept in flimsy canvas tents exposed to the elements and feared for their security.

Figure 2. Kara Tepe Camp, August and December 2015

Photos: Joel Hernandez, Anita Makri

Many of the concerns and recommendations outlined by Morlet and other organizations have since been addressed by the IRC, MSF, other international NGOs, local organizations, and municipal authorities, acting under UNHCR coordination. In October, UNHCR purchased 250 Refugee Housing Units (RHUs) from the Ikea Foundation for deployment in Lesvos; 158 of these rigid structures (intended to house eight occupants, but with a capacity of up to 20 each) comprise Kara Tepe’s shelter stock, while 62 RHUs provide overflow housing in Moria. The rest function as storage and distribution centers for NGOs in the camps as well as in northern Lesvos. As of December, the author observed that Kara Tepe’s grounds were clean and trash collection operated effectively, its water points and washing facilities were sanitary, and the camp was well lit and featured solar-powered wifi hotspots for use by responders and asylum seekers alike.

Kara Tepe’s pool of professional responders from a range of international NGOs has grown from a dozen last summer to around 70 as of January 2016. Oxfam International distributes food and blankets, Médecins du Monde and Humanitarian Appeal manage field clinics, the Greek Red Cross runs non-food distribution centers, the IRC provides shelter and camp management and operates water points, and MSF and Praksis (a Greek NGO) provide safe spaces for children and single mothers to pass time and access protection. Humanitarian Support Agency (HSA), Morlet’s organization, operates distribution programs for food and other items, complementing those of the international organizations at Kara Tepe.

Integrating Professional and Volunteer Efforts at Moria

While the evolution of conditions at Kara Tepe demonstrates the positive results of cooperation between professional humanitarian providers and volunteer organizations, Moria illustrates the challenges of meshing such relationships.

Moria’s “interior” camp was built in the spring of 2014 with European Union and Greek funding on a former military base near the village. The camp is operated by Greek police and represents the main EU hotspot in Lesvos. The interior camp is enclosed by razor-wire fencing, with dormitory-like shelter in 11 large, prefabricated structures maintained by Greek authorities. The IRC, Médecins du Monde, MSF, Praksis, and UNHCR provide relief services in the camp, while Greek police maintain order, Frontex carries out screening, and Greek Interior Ministry officials manage registration. Staffed by about 30 professional humanitarians last summer, Moria now has about 140 aid workers. The camp’s facilities only have capacity for about 700 occupants. Even when augmented by 62 RHUs that provide capacity for approximately 1,000 additional asylum seekers, this falls far short of total need (Greek police reported between 3,000 and 6,000 daily arrivals in Moria in October).

In response to this shortfall, volunteer organizations set up an “exterior” camp in October, on a sloping olive grove immediately adjacent to Moria. Though the infrastructure of this overflow area is considerable—featuring a clinic, child-friendly area, enclosed restrooms, mosque, kitchens, and tea distribution center—problems are legion. Human Rights Watch Emergencies Director Peter Bouckaert, in a November visit, observed asylum seekers sleeping outside, surrounded by squalor, crowds jostling and fighting for access to the registration center, and parents and pregnant mothers fearing for their safety and that of their children. For want of rigid-structure shelters, asylum seekers in the exterior camp are housed in tents of varying size and quality that provide limited protection from wind and rain and little insulation from winter temperatures. In late December 2015, Starfish Foundation began distributing firewood to give residents an alternative to burning garbage in order to keep warm.

Though adjacent to each other and serving the same population, the two camps largely operate independently of each other, with divergent resources and personnel levels. There is little sharing of resources, information, or facilities—in sharp contrast to the well-integrated responses in northern Lesvos and at Kara Tepe—and tensions between volunteers, who complain they are shunted aside by the large NGOs, and professional humanitarians wary of working alongside untrained volunteers. As a result, Moria also showcases stark disparities between the well-managed but insufficient interior camp, and the well-intentioned but overwhelmed exterior camp.

Moria: EU Hotspot

In May, the European Union proposed the development of a new “hotspot” approach, concentrating resources at designated sites in frontline states including in Lampedusa, Sicily, southern Italy, and the Greek islands of Lesvos, Chios, Samos, Leros, and Kos. Hotspots receive personnel and equipment from EU agencies to work with local authorities to quickly identify, register, and fingerprint migrants and asylum seekers. Though the main goal is to register and document all arrivals, hotspot personnel are also supposed to screen out migrants without protection needs and coordinate their repatriation, while processing the applications of asylum seekers with legitimate claims and relocating them to other EU Member States under a plan proposed by the European Commission in September.

On October 15, the European Union established a hotspot screening center and registration site in Moria, and the following week opened a registration site for Syrians in Kara Tepe. However, the application of stricter screening and processing measures combined with the sheer number of cases overwhelmed the Moria site. In the resulting backlogs, thousands of asylum seekers and migrants waited for days at a time with little aid provision—eating, sleeping, and braving foul weather while waiting in line to register. While Kara Tepe’s registration site proved somewhat more efficient (partly because EU and Greek officers there do not need to screen for nationality), Syrians have also faced registration wait times between several hours and a full day. Because the European Commission’s migrant relocation scheme has been slow to implement, the Lesvos hotspot has struggled to fulfill part of its mission to relocate asylum seekers and remove other migrants. As of 2016, both individuals deemed to have legitimate protection claims and other migrants have been allowed to transit from Lesvos to Athens with temporary authorization granted by Greek authorities and then continue their journeys toward northern Europe. Though the hotspot infrastructure has provided a degree of order and dramatically improved the documentation of arrivals in Lesvos, EU personnel and resources have been sorely strained.

Tensions at the Port and Onward Bottlenecks

Once registered with Greek authorities, asylum seekers at Kara Tepe and Moria face a final hurdle: buying a 60-euro ticket for a ferry to mainland Greece. In late August, bottlenecks developed as the regular ferry service fell short of the rapidly increasing demand. Crowded out of the transit camps, asylum seekers began pitching tents in the port of Mytilene itself. Riots broke out in early September, as asylum seekers gathered in the port without access to water, food, or bathrooms, while facing a stifling heat wave, petty harassment by overstretched local police, and occasional hostility from locals. It took a contingent of riot police to pacify the port, and order was finally restored in mid-September with the provision of additional ferries by the Greek government and European shipping companies. A shipping strike that grounded ferry traffic across the Aegean from November 2-6 not only stoked a resurgence in tensions, but imperiled deliveries of food and much-needed supplies to Lesvos and other transit islands.

Through its port and frequent ferry traffic, Lesvos had an existing infrastructure for transit to the Greek mainland, but was unprepared to meet the humanitarian needs of those passing through or the unprecedented numbers, particularly at the height of the summer tourist season. Over the course of 2015, the unabated flow of asylum seekers spurred the development of an extensive reception infrastructure—the maintenance of which is crucial to normal operation at points further upstream. Bottlenecks at the port created a domino effect, provoking backups at Kara Tepe and Moria, and in turn at the Oxy camp in northern Lesvos. As the asylum seekers and migrants have moved on through mainland Europe, these backups and resulting tensions and violence have been reproduced at border crossings across the Balkans, highlighting the need to provide for and accommodate onward movement as well as reception.

Challenges Ahead

Though the humanitarian response observable in Lesvos in January 2016 was much improved from that of the previous summer, its success or failure hinges on a multitude of factors, many of which cannot be predicted and only some of which can be controlled. Chief among them: The arrival of asylum seekers in still vast numbers. Despite the winter’s choppier waters, crossings persisted through December in numbers comparable to those of August. It remains very much to be seen how effective an agreement reached by the European Union and Turkey in November 2015 will be, once fully implemented, in halting the flow of asylum seekers across the Aegean.

Greek authorities have undertaken immense effort to manage the refugee crisis even as their country reels under sharp austerity measures. Yet their behavior has also confounded humanitarian efforts. For example, volunteer responders ferrying asylum seekers across the island by vehicle or supporting seaborne rescue operations occasionally have been arrested under the pretext that they were facilitating illegal migration. Communication between Greek authorities and responders sometimes has been problematic as well. In January 2016, Morlet reported that the municipality of Molyvos cut off food distribution in Kara Tepe without warning, temporarily halting programs from HSA, OXFAM, and Save the Children that were providing 2,000 meals daily. UNHCR has reported that Greek police have changed the location of registration activities between Kara Tepe and Moria on several occasions, with little or no prior warning to humanitarian agencies.

Tensions between established international NGOs and local volunteer organizations also have flared occasionally, especially when professional providers began running programs in areas that until then had largely been the province of volunteers. Observable contrasts between the efficient services provided in northern Lesvos and at Kara Tepe by international NGOs and the enduring challenges in Moria’s volunteer-run camp illustrate the ongoing challenges in integrating humanitarian operations.

And beyond the shelter, food, and material items provided to asylum seekers upon arrival in Lesvos, there remains an unmet need: Concerted psychosocial support to manage the shock of the dangerous journey many have experienced and to help them prepare for life in a society and culture far different than what they have known.

Humanity, compassion, and care are in ample supply in Lesvos. The hard-fought lessons of 2015 learned by volunteers, professional providers, and authorities alike can lay the groundwork for a much improved response in the year ahead.

The author volunteered in Lesvos in July-August and December 2015, and returned in January 2016 to work as Program Director with Humanitarian Support Agency.

Sources

Bouckaert, Peter. 2015. Lesbos' Refugee Disaster. Foreign Affairs, November 11, 2015. Available Online.

Bunyan, Tony, John Moore, and Ann Singleton. 2014. Welcome to the European Union: Visit to Moria First Reception Centre, Moria, nr. Mytilini, Lesvos, Greece, 11th May 2014. Statewatch.org, July 19, 2014. Available Online.

Butte-Dahl, Jennifer. 2015. An aid worker tells the harrowing story of one Syrian family’s escape to Greece. Quartz, September 16, 2015. Available Online.

Carstensen, Jeanne. 2016. Greece: the Ghosts of Refugees Past. Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, January 4, 2016. Available Online.

European Commission. N.d. The Hotspot Approach to Managing Exceptional Migratory Flows. Accessed January 20, 2015. Available Online.

---. 2016. State of Play of Hotspot capacity. Last updated January 26, 2016. Available Online.

Hilton, Jodi. 2016. Is Greece right to rein in refugee volunteerism? IRIN News, January 19, 2016. Available Online.

Hubbard, Ben. 2015. Waves of Young Syrian Men Bring Hope, and a Test, to Europe. The New York Times, October 7, 2015. Available Online.

Kakissis, Joanna. 2015. To Keep Track Of Migrants, EU Sets Up 'Hot Spots.' National Public Radio, November 3, 2015. Available Online.

Morlet, Frédéric. 2015. Kara Tepe, transit camp for refugees, Lesvos (Greece). Statewatch.org, August 18, 2015. Available Online.

---. 2015. Volunteer, UNICEF-Spain. Skype interview with author. October 1, 2015.

---. 2015. Director, Humanitarian Support Agency. Personal Interview. December 29, 2015.

Niarchos, Nicholas. 2015. An Island of Refugees. The New Yorker, September 16, 2015. Available Online.

Paone, Mariangela. 2015. Óscar Camps: ángel español en la isla de Lesbos [Spanish angel on the island of Lesbos]. El Español, December 31, 2015. Available Online.

REACH Initiative. 2015. The European Migrant Crisis Situation Overview: Lesbos, Greece. Geneva: REACH Initiative. Available Online.

Save the Children International. 2015. Multi-Sector Needs Assessment of Migrants and Refugees in Greece. London: Save the Children International. Available Online.

Starfish Foundation. 2016. Farewell Oxy. Starfish Foundation blog, January 8, 2016. Available Online.

Stevis, Matina. 2015. Volunteers Flock to Greek Island to Fill Void in Migrant Crisis. Wall Street Journal, December 10, 2015. Available Online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2015. Greece Refugee Emergency Response—Update #6. Athens: UNHCR. Available Online.

---. 2015. Greece Refugee Emergency Response—Update #7. Athens: UNHCR. Available Online.

---. 2015. Update on Lesvos and the Greek islands. News release, November 6, 2015. Available Online.

---. 2016. Lesvos Island Snapshot – 18 January 2016. Available Online.

UNHCR and MapAction. 2016. Greece: Key Locations on Lesvos, January 14, 2016. Available Online.

Vickery, Matthew. 2015. At The Captain's Table: The restaurant helping refugees. Al Jazeera, October 13, 2015. Available Online.