You are here

Refugees and Asylees in the United States

A family of Burmese refugees arrives in the United States. (Photo: Chad Nelson/World Relief)

The United States is the world’s top resettlement country for refugees. For people living in repressive, autocratic, or conflict-embroiled nations, or those who are members of vulnerable social groups in countries around the world, migration is often a means of survival and—for those most at risk—resettlement is key to safety. In fiscal year (FY) 2015, the United States resettled 69,933 refugees and in FY 2013 (the most recent data available) granted asylum status to 25,199 people.

By the end of 2014, as wars, conflict, and persecution worldwide continued to unfold, the number of people displaced within their country or having fled internationally reached 59.5 million, according to estimates by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)—the highest level ever recorded. And by mid-2014 there were more than 1.2 million asylum seekers worldwide. Ongoing war in Syria alone has led more than 4.1 million people to seek refuge in neighboring countries and beyond and to the internal displacement of more than 7.6 million Syrians.

In response to this humanitarian crisis, the Obama administration proposed to significantly increase the number of refugees the United States accepts each year—from 70,000 in FY 2015 to 85,000 in FY 2016 and 110,000 in FY 2017—and scale up the number of Syrian refugees admitted to at least 10,000 for the current fiscal year, which began October 1.

The United States offers humanitarian protection to refugees through two channels: refugee resettlement and asylum status. Using the most recent data available, including 2015 refugee arrival figures from the State Department, the Department of Homeland Security’s 2013 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, and administrative data from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and the Department of Justice’s Executive Office for Immigration Review, this Spotlight examines characteristics of the U.S. refugee and asylee population including the admissions ceiling, top countries of origin, and U.S. states with the highest resettlement. It also explores the number of refugees and asylees who have become lawful permanent residents (LPRs), followed by an explanation of the admissions process.

Definitions

Refugees and asylees are individuals who are unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin or nationality because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution. Refugees and asylees are eligible for protection in large part based on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion. The 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act expanded this definition to include persons who have been forced to abort a pregnancy, undergo a forced sterilization, or have been prosecuted for their resistance to coercive population controls.

In the United States, the major difference between refugees and asylees is the location of the person at the time of application. Refugees are usually outside of the United States when they are screened for resettlement, whereas asylum seekers submit their applications while they are physically present in the United States or at a U.S. port of entry. Refugees and asylees also differ in the admissions process and the agency responsible for reviewing their application.

Note: All yearly data are for the government's fiscal year (October 1 through September 30).

Click on the bullet points below for more information:

- Refugee Admission Ceiling

- Refugee Arrivals

- Refugee Countries of Origin

- Top Refugee-Receiving U.S. States

- Asylees

- Adjusting to Lawful Permanent Resident Status

- Admissions Process

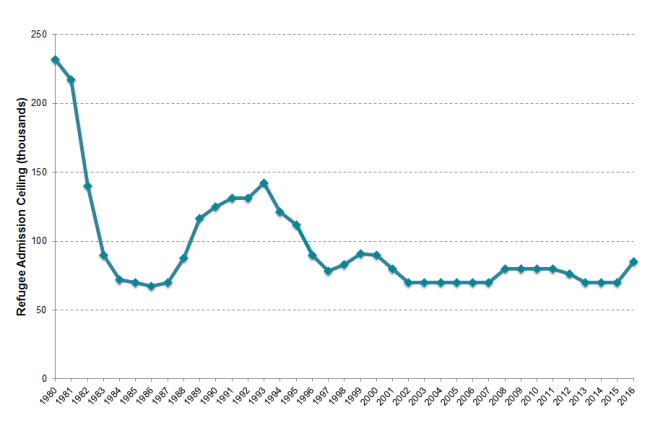

The number of persons who may be admitted as refugees each year is established by the president in consultation with Congress. At the beginning of each fiscal year, the president sets the number of refugees to be accepted from five global regions, as well as an “unallocated reserve” if a country goes to war or more refugees need to be admitted regionally. In the case of an unforeseen emergency, the total and regional allocations may be adjusted.

After the most recent peak of 142,000 in 1993 (largely as a response to the Balkan wars), the U.S. annual refugee admission ceiling steadily declined. In 2008, however, the ceiling was raised by 10,000 to accommodate an expected increase in refugee resettlement from Iraq, Iran, and Bhutan. From 2008 to 2011, the annual ceiling remained at 80,000; it was reduced to 76,000 in 2012, and further reduced to 70,000 since 2013 (see Figure 1).

The Obama administration’s proposal to significantly increase the number of worldwide refugees the United States accepts annually up to 100,000 in FY 2017 would mark the largest yearly increases in refugee admissions since 1990.

The proposed 85,000 worldwide ceiling for FY 2016 would include 10,000 Syrians and is further broken down into regional caps: 34,000 resettlement places for refugees from the Near East and South Asia (up 1,000 from 2015); 13,000 from East Asia (no change); 25,000 from Africa (up 12,000); 3,000 from Latin America and the Caribbean (down 1,000); and 4,000 from Europe and Central Asia (up 3,000). The unallocated reserve also increased from 2,000 in 2015 to 6,000 in 2016.

Figure 1. U.S. Annual Refugee Admission Ceilings, FY 1980-2016

Source: U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, “Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year,” various years.

Click here for a factsheet on U.S. refugee resettlement.

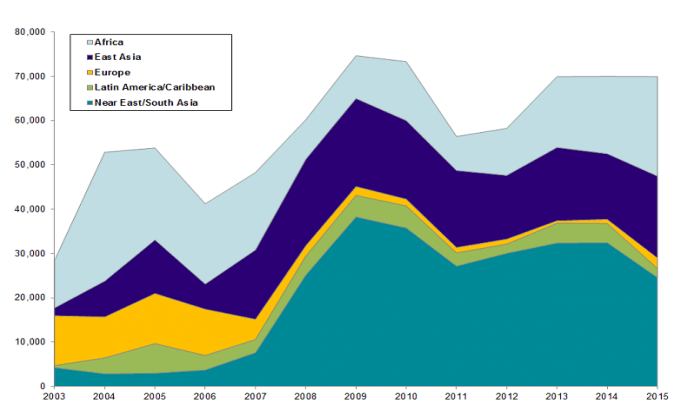

In FY 2015, 69,933 individuals arrived in the United States as refugees, according to data from the State Department’s Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System (WRAPS). This is very close to the number of refugees resettled in 2013 (69,926) and 2014 (69,987), but 20 percent higher than the 2012 total (58,238, see Figure 2).

In FY 2015, 40 percent of refugee arrivals, or 28,066 individuals, were principal applicants.

Note: Eligible family members who are granted follow-to-join refugee status are included in the refugee admissions data. The asylee data show them separately.

Figure 2. U.S. Refugee Arrivals by Region of Nationality, FY 2003-15

Note: Data from the Department of State (DOS) Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System (WRAPS) on refugee arrivals differ slightly from the Department of Homeland Security’s Yearbook of Immigration Statistics due to a different data counting approach.

Source: MPI analysis of WRAPS data from the DOS Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration, available online.

Refugee Countries of Origin

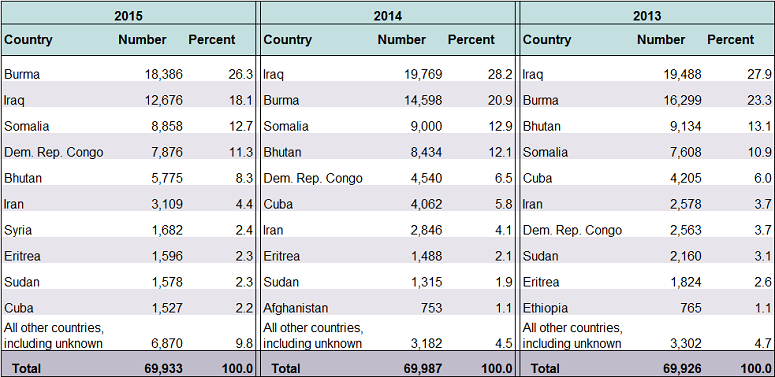

Nationals of Burma (also known as Myanmar), Iraq, and Somalia were the top three countries of origin for refugees in 2015, representing 57 percent (39,920 individuals) of resettlements (see Table 1). Rounding out the top ten countries were: the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Bhutan, Iran, Syria, Eritrea, Sudan, and Cuba.

There has been a significant decline in the number of refugees from Iraq, Bhutan, and Cuba in recent years. Iraq was the top refugee origin country in 2013 and 2014, accounting for 28 percent of refugees resettled; the share of Iraqis dropped to 18 percent in 2015. Bhutanese are down to 8 percent of refugee arrivals in 2015, compared to 13 percent in 2013 and 12 percent in 2014. From 2014 to 2015, the number of Cuban refugees decreased from 6 percent to 2 percent (see Table 1).

Meanwhile, refugees from Burma, DRC, and Iran witnessed moderate increases. Burma, the top origin country in 2015, was the second-largest refugee origin country in 2013 and 2014. The number of refugees from DRC increased from 4 percent in 2013 to 11 percent in 2015.

Table 1. Top Ten Origin Countries of Refugee Arrivals, FY 2013-15

Source: MPI analysis of WRAPS data.

In recent years, the number of Syrian refugees resettled in the United States grew rapidly: from 31 in 2012 to 1,682 in 2015. As of mid-2015, UNHCR had referred more than 15,000 Syrian refugees to the United States for resettlement, who are being screened to determine their eligibility. The usual vetting time for Syrian refugees is 18 to 24 months, according to the State Department.

In December 2014, the Obama administration established an in-country refugee and parole program for children in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras under age 21 whose parents are lawfully present in the United States. As of August 2015, parents had submitted nearly 3,000 applications, and children were being interviewed to determine their eligibility. Because the majority of applications were received from May to July, very few such minors were admitted in FY 2015; current estimates suggest there will be a modest increase in the number of admissions in FY 2016.

Click here to read a report on in-country processing in Central America.

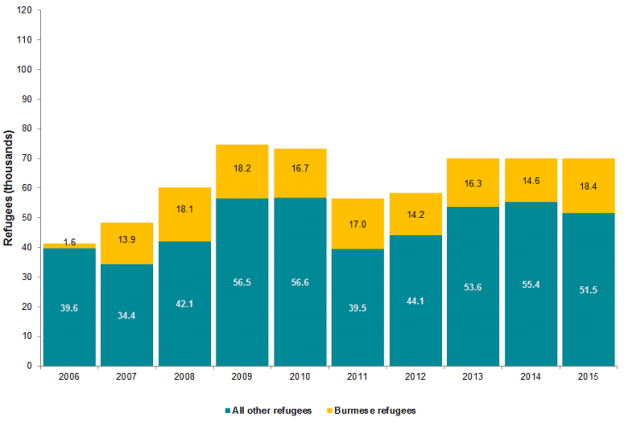

In the past decade, Burmese have been the largest group of refugees resettled to the United States with 148,957 (or 24 percent) of the 622,169 resettled since 2006. The next two groups are Iraqis (125,970, or 20 percent) and Bhutanese (84,547, or 14 percent).

Figure 3. Number of Admitted Burmese and All Other Refugees FY 2006-15

Source: MPI analysis of WRAPS data.

Top Refugee-Receiving U.S. States

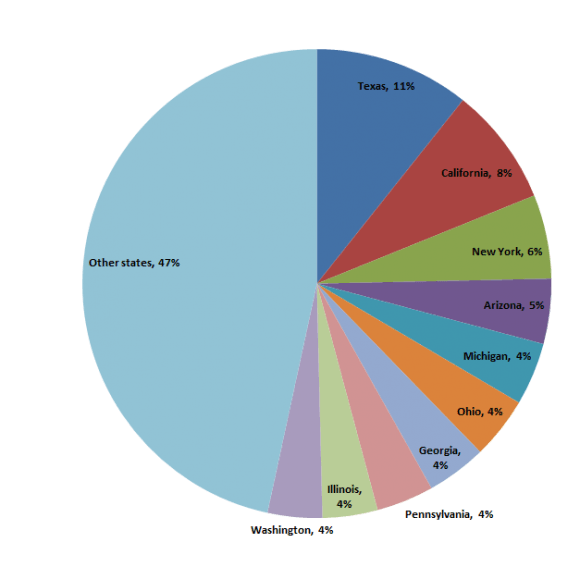

In 2015, as in the prior year, the largest shares of refugees arriving in the United States were resettled in Texas (11 percent, or 7,479 persons) and California (8 percent, or 5,716). Relatively large shares were also resettled in New York (6 percent, or 4,052), Arizona (5 percent, or 3,137), Michigan (4 percent, or 3,022), and Ohio (4 percent, or 2,989). Thirty-eight percent of all refugees were resettled in these top six states (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Refugee Arrivals by Initial State of Residence, 2015

Source: MPI analysis of WRAPS data.

Asylees

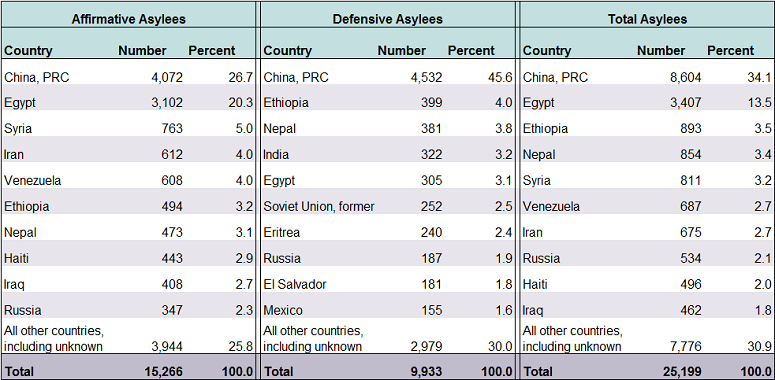

In FY 2013 (the most recent data available), 25,199 persons were granted asylum either affirmatively or defensively, a 14 percent drop from 29,367 in 2012, according to the DHS Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Sixty-one percent (15,266) were granted asylum affirmatively; 39 percent (9,933) were granted asylum defensively.

An additional 13,026 individuals who resided outside the United States were approved for derivative follow-to-join status as immediate family members of principal asylum applicants. (Note that this number reflects travel documents issued to these family members, not their arrival to the United States.) In addition, 2,240 individuals were approved for derivative asylum status while in the United States in 2013.

Nationals of China, Egypt, and Ethiopia accounted for 52 percent (or 12,904) of all persons granted affirmative or defensive asylum status in FY 2013 (see Table 2). Notably, the number of Syrians who received asylum status grew from 60 in 2011 to 364 in 2012, and more than doubled to 811 in 2013.

Table 2. Affirmative, Defensive, and Total Asylees by Country of Origin, 2013

Source: Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Immigration Statistics, 2013 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, available online.

Between FY 2012 and FY 2014, Syrian nationals filed 694 defensive asylum claims and 3,415 affirmative asylum applications with the Department of Justice and USCIS. A total of 1,396 applications were approved (141 defensive and 1,255 affirmative). A significant number are still under review due to large asylum processing backlogs.

Adjusting to Lawful Permanent Resident Status

Refugees must apply for lawful permanent resident (LPR) status—also known as getting a green card—one year after being admitted to the United States. Asylees become eligible to adjust to LPR status also after one year of residence, but are not required to do so. As lawful permanent residents, refugees and asylees have the right to own property, attend public schools, join certain branches of the U.S. armed forces, travel internationally without an entry visa, and may apply for U.S. citizenship five years after being admitted as a refugee.

Until 2005, there was an annual limit of 10,000 on the number of asylees authorized to adjust to LPR status. The implementation of the REAL ID Act eliminated that cap. No annual limit exists on the number of refugees eligible to adjust to LPR status.

In 2013, 119,630 refugees and asylees adjusted their status to lawful permanent residence, of which, 65 percent (or 77,395) were refugees and 35 percent (42,235) were asylees (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Refugees and Asylees Granted Lawful Permanent Residence, FY 1995-2013

Source: DHS, Office of Immigration Statistics, 2013 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics.

Admissions Process

Refugees

Section 207(c) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) grants the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) the authority to admit any refugee who is determined to be of special humanitarian concern and admissible to the United States. The majority of refugees accepted for resettlement are referred by UNHCR and admitted as Priority 1 cases; referrals by a U.S. embassy or nongovernmental organization (NGO) comprise a much smaller subset of cases. The U.S. refugee admissions program is as follows.

- Priority 1 (P-1): Individual cases referred by virtue of their circumstances and apparent need for resettlement. Individual refugee cases are identified and referred to the U.S. resettlement program by UNHCR, a U.S. embassy, or a designated NGO.

- Priority 2 (P-2): Groups of cases designated by virtue of their circumstances and apparent need for resettlement. This includes in-country processing programs for minors in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras; Iraqis employed by the U.S. government and military in Iraq; and Cubans subjected to harsh treatment for political or religious reasons.

- Priority 3 (P-3): Individual cases from designated nationalities for purposes of reunification with family members already in the United States. Due to a high incidence of fraud, the P-3 processing program was suspended for a time and was resumed in October 2012 after significant changes.

Note: Within two years of admission, a refugee may submit a “follow-to-join” form to USCIS to allow a spouse or unmarried children below age 21 to be resettled in the United States.

All refugees under consideration for resettlement regardless of priority category are vetted through multiple security screenings and intensive background checks—by DHS, intelligence agencies, the State Department, and the FBI—in a process that takes on average 18 to 24 months. Once refugees receive conditional approval for resettlement, they are guided through a process of medical screenings, cultural orientation, sponsorship assurances, and referral to the International Organization for Migration (IOM) for transportation to the United States.

Asylees

According to the U.S. Refugee Act of 1980 and based on the 1951 UN Refugee Convention, any noncitizen who is physically present in the country or at a port of entry may apply for asylum, regardless of his or her current immigration status. An asylum seeker present in the United States may decide to submit an asylum request either with a USCIS asylum officer voluntarily at a time of their own choosing (affirmative request), or, if apprehended, with an immigration judge as part of a removal hearing (defensive request). During the interview, an asylum officer will determine whether the applicant meets the definition of a refugee.

If the case is denied, an applicant may appeal for additional hearings with the Board of Immigration Appeals or, in some cases, with federal courts.

Noncitizens may also request asylum at a port of entry by informing an inspection officer that he or she is fleeing persecution or seeking asylum. The individual is then referred to an asylum officer for a credible fear interview to determine if he or she has a verifiable fear of persecution. If the claim is denied, the individual is subject to removal.

People may also be eligible to derive asylum status as spouses or children (unmarried and under 21) of the principal asylee either at the time of asylum application or at a later date as long as the asylum application has been approved, the status has not been revoked, and the relationship of the principal applicant to the family members has not changed since the time of the case approval.

Once granted U.S. protection, both refugees and asylees are entitled to a social security card and employment authorization. Depending on the individual’s or household’s needs and the length of time that has passed since their arrival or asylum status was granted, they may qualify to receive assistance including cash, medical, housing, educational, and vocational services to promote economic self-sufficiency and integration into society.

Sources

Capps, Randy and Michael Fix. 2015. Ten Facts about U.S. Refugee Resettlement. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available Online.

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. N.d. Refugee Processing Center - Admissions & Arrivals. Accessed October 16, 2015. Available Online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2015. Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2014. Geneva: UNHCR. Available Online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2015. Asylum Applications Filed by Nationals of Syria. Available Online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Immigration Statistics. 2014. 2013 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Washington, DC: DHS, Office of Immigration Statistics. Available Online.

U.S. Department of Justice, Executive Office for Immigration Review. 2015. Asylum Statistics FY 2010-2014. Available Online.

U.S. Department of State, Department of Homeland Security, and Department of Health and Human Services. 2015. Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2016: Report to the Congress. Washington, DC: Department of State. Available Online.