Russia Beckons, But Diaspora Wary

Russian President Vladimir Putin has pinned the hopes for stemming his country's steep population decline on an increase in return migration by well-educated Russians and Russian speakers. The dream is that more of the 25.2 million Russians living in the former Soviet Union (FSU) at the time of 1989 census, just prior to the breakup, will flock to their homeland. But with net migration waning since a 1994 peak, legislators moving to limit immigration to screen out "undesirables," and uncertainties looming over integration efforts, it is unclear how this dream can be translated into reality.

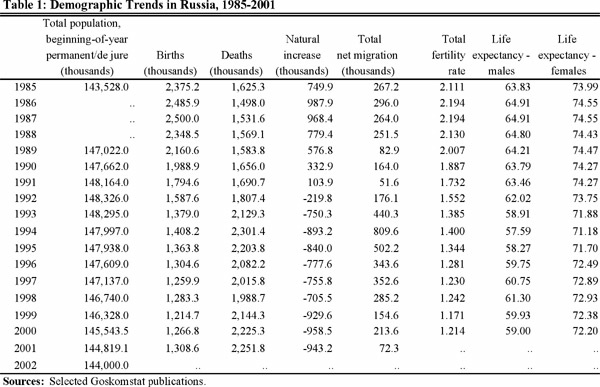

Russia has reason to fret over the gain or loss of migrants, since the latest figures indicate that its morgues are busier than its maternity wards. This trend, now a decade old, has had staggering demographic consequences. According to recently released official estimates, the Russian population stood at 144 million as of New Year's 2002, a drop of 4.3 million from a 1992 peak. In fact, the trends of extremely negative natural decrease (the excess of deaths over births) and slowing migration appear to have grown stronger since 1998.

In each of the last three years, the natural decrease of the population was over 900,000. In 2001, net immigration into Russia compensated for only 8 percent of this decline, and the population fell by 820,000.

In each of the last three years, the natural decrease of the population was over 900,000. In 2001, net immigration into Russia compensated for only 8 percent of this decline, and the population fell by 820,000.

Demographic Titanic

Russian policy makers' preoccupation with migration is best understood in light of the trends that are driving down natural increase. The latest figures reveal a complex problem in which a soaring death rate is only the tip of the iceberg.

Although the "mortality crisis" of high increases in deaths among middle-aged men from cardiovascular disease and external causes of the death (murder, suicide, accidents, poisoning) has received the greatest attention, it is actually the decline in the birth rate that has had the greatest impact on population decline. Since 1987, the number of deaths has increased by 720,000 while the number of births has declined by 1,191,000.

Taken as a whole, the ratio of deaths to births is far higher in Russia than in other countries. In Russia, there are about 1.7 deaths for each birth, while in aging, low-fertility countries in Europe such as Germany, Italy, and Spain, the number of deaths barely exceeds the number of births.

Analysts looking at the intersection of Russian birth and death rates note that the situation started in 1992, the first year of Russia's independence, and often refer to the situation as the "Russian cross." While coincidental, the two events are not correlated, and the negative natural decrease is partially attributable to the aging of the Russian population and the peculiarities in the country's age structure.

Harvesting Data

Just who is left in Russia? The logical tool for resolving this debate might be the October 2002 Census, whose results are eagerly anticipated given Russia's size and dramatic demographic upheavals over the past decade. Russia will be one of the last transition countries in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe to conduct its first post-breakup, post-transition census.

The recently released population estimates will likely be the last before Russia conducts the census.

As the chart indicates, in 2001, Russia saw return migration of only 72,300, less than 10 percent of the 1994 peak when net immigration to Russia reached over 800,000 people.

From 1990 to 1999, emigration from Russia to beyond the FSU states averaged about 100,000 annually. By 2001, this exodus of mostly, skilled, educated persons had fallen by half to 51,400. The net migration exchange with the countries of the former Soviet Union has had the largest impact on overall migration levels. In the peak year of 1994, 1.1 million people immigrated to Russia from the non-Russian FSU states while in 2001, this figure had fallen to just 186,200.

These trends could be rather easily explained by the decline in Russia's GDP following the 1998 ruble crisis. However, combined with uncertain levels of illegal migration, they paint a rather complex and murky picture.

Figures for the number of illegal migrants in Russia range from 700,000 up to a rather implausible 15 million. One rather contradictory statement read "according to official data, at the end of 2001 in Russia, there were 5 million illegal migrants." Anecdotal information indicates that most of these people enter Russia legally and then overstay their visas, and that most are from the other FSU states as well as large numbers from Southeast Asia. There will be a special section in the upcoming census designed to ascertain the size, composition, and long-term motives of this undocumented population.

Regardless of the exact figure, the range of numbers seems to indicate that willingly or not, Russia is at the minimum becoming a migration magnet in a region beset by a variety of economic, cultural, and political crises.

Uncertainties Ahead

For many reasons, Russia's migration policy in the new century will be problematic. First, Putin's hopes for a regulated influx of legal "Russian" migrants puts it on the course of many other migration magnet countries, which encourage legal migration of certain groups while discouraging that of others. The record shows that most fail miserably at this balancing act.

For many reasons, Russia's migration policy in the new century will be problematic. First, Putin's hopes for a regulated influx of legal "Russian" migrants puts it on the course of many other migration magnet countries, which encourage legal migration of certain groups while discouraging that of others. The record shows that most fail miserably at this balancing act.

In the same vein, the former superpower may find itself hosting plenty of migrants of the kind it is not seeking out, which will raise issues of integration. While the extent of criminality often attributed to groups of undocumented migrants in Russia may be overstated, it is likely that they are living on the fringes of society.

If it is the case that many are from outside the FSU and lack Russian-language skills, then their incorporation into Russian society may be more problematic. Moreover, if current policies are any indication, that hardly appears to be what Putin and others desire.

Meanwhile, the fact that Russians abroad are giving a chilly reception to appeals from their compatriots may put official plans for a grand homecoming of ethnic Russians on ice. In fact, the government already seems to be shifting its policy to cope with what it views as a rather chaotic migration stream. This change has been signaled by the success of a more restrictive citizenship bill that has already passed the Duma (lower house). Passage in the Federation Council (upper house) is considered a formality, and the bill is expected to become law this summer.

The new legislation stipulates a five-year residency requirement, demonstrable Russian-language skills, and proof of employment. The law does not give preferential treatment to the remaining Russian diaspora population (about 12 percent of the 25.2 million have "returned" since 1989), who previously could obtain Russian citizenship fairly simply at consulates abroad.

This move toward a more restrictive policy seems to mark a triumph by elements in the government whose main concern is keeping out those they consider "undesirables," such as Chinese, Afghans, and Central Asians. With the passage of this law by the Duma, they have apparently overridden the concerns of Putin and others who wanted a more open policy to encourage more Russians to return. Working in the favor of the pro-restriction camp, it appears, is the prime minister's own vacillation on the issue, and his belated realization of how difficult it is to "regulate" migration.

For the time being, Putin's job does not look set to become any easier. Rather than laying the migration issue to rest, the new legislation has sparked further controversy by failing to adequately address the status of permanent non-citizen residents, guest workers, and other key elements of the migration stream. This, coupled with the specter of a shrinking population, fears of integration difficulties, and a diaspora population wary of returning home, will undoubtedly demand Russia's attention for years to come.