You are here

Spiraling Violence and Drought Drive Refugee Crisis in South Sudan

A girl carries her family's belongings to a UN base in Juba, South Sudan. (Photo: Anita Kattakhuzy/Oxfam)

The world’s youngest country, South Sudan has been at the epicenter of an array of destructive dynamics almost since its independence from Sudan in 2011. Violent conflict, severe drought, and man-made famine have coalesced to create a catastrophe affecting millions of people. The intersection of crises has displaced nearly 4 million South Sudanese, about half of whom have fled to neighboring countries, mainly Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, and Uganda. The humanitarian emergency is one of the fastest-growing in the world, and the refugee crisis is Africa’s largest since the Rwandan genocide in 1994. The emergency has been classified by the United Nations as among the most severe in the world, alongside those in Syria, Iraq, and Yemen.

Widespread hunger is a key driver of displacement. Millions of South Sudanese do not have access to food and cannot grow crops. In February 2017, the United Nations, South Sudan, and the U.S.-based Famine Early Warning Systems Network formally declared famine in two South Sudan counties, the first such declaration since Somalia’s in 2011. While the designation was lifted four months later, following the rapid mobilization of international humanitarian assistance, some 6 million people still struggle to find enough food. More than 1.1 million children suffer from malnutrition, including 290,000 in need of urgent care. Beyond South Sudan, the drought has also created increasingly severe food shortages in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia.

There is not a single root cause that explains all displacements and famines; each context is unique. The factors in South Sudan, including violent conflict, political and economic insecurity, chronic poverty, lack of trade, and severe climate conditions such as persistent drought, make for a particularly lethal combination.

This article explores the interaction of conflict and drought driving the South Sudan displacement crisis, examines refugee flows to neighboring countries, and discusses prospects for sustainable solutions.

Overview of the Conflict

The area now recognized as South Sudan has experienced waves of armed conflict since the 1950s. More than 2.5 million people were killed during the region’s longest civil war, from 1983 to 2005, and tens of millions of lives were affected. Primarily seen as a North-South dispute over resources and political control, the conflict between the Sudanese government and the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M) intensified upon the discovery of oil in the 1980s. The war ended in 2005 following political negotiations, and a referendum on independence was held, resulting in independence in 2011.

High hopes for the young nation were dashed two years later, when South Sudan again plunged into violent conflict. A rivalry between President Salva Kiir of the Dinka ethnic group and then-Vice President Riek Machar, of the Nuer, escalated into ethnic-tinged violence after Kiir fired Machar for allegedly plotting a coup. The majority Dinka and the minority Nuer are the two largest groups in South Sudan and have a history of bloody feuding. Government forces have targeted civilians in areas of high Nuer concentration, claiming their aim is to push back against rebel fighters.

The United Kingdom has described the killings in South Sudan as a genocide. Though the United Nations has not yet made a determination, the UN Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide warned that the war could escalate into genocide. Red flags include extreme ethnic polarization, fueling a cycle of revenge; frequent acts of hate speech and inflammatory stereotyping; widespread and systematic attacks against civilians on the basis of ethnic background; atrocities intended to dehumanize certain groups; and targeted killings and rapes. The situation is intensifying as the government of South Sudan has lost its monopoly over coercive power, and its ability to deliver public services, provide basic security, and administer justice is now virtually nonexistent. Further, UN peacekeepers have not been able to stop the atrocities.

Since December 2013, at least 50,000 people have been killed, with millions of others either displaced or left severely food insecure. South Sudan’s northern region has been the most devastated by conflict and ensuing food insecurity and displacement. Conditions in the south began deteriorating after fighting broke out in Juba in mid-2016. The intensification of violence has hampered aid delivery to vulnerable populations across the country.

Food Insecurity: Man-Made Crisis, Exacerbated by Nature

Severe food insecurity is one of the major consequences of the conflict. Though a prolonged drought has contributed to food shortages, the crisis is primarily man-made. When millions of people are forced to flee violence—including farmers, shopkeepers, and others involved in producing and distributing food—it becomes difficult to ensure everyone has enough to eat. Plants and cattle have been abandoned, and overall agricultural production has fallen by half. The conflict has adversely affected the ability of South Sudanese to participate in the economy by earning a livelihood or trading with other countries. Meanwhile, many families flee to the marshlands in central South Sudan, which provide cover from fighters—but little food.

The drought can be attributed to regional climate changes over the last 30 years. South Sudan is one of the most rapidly warming countries in the world, with temperatures increasing two and a half times more than average global warming. The warming is making normal years drier, while counterintuitively increasing flood frequency in some areas. This trend is also endemic in neighboring countries, including Ethiopia and Kenya, affecting not only crop yields and livestock, but by extension livelihoods, health, and education.

While South Sudan has a large agricultural sector, only about 4 percent of its land is consistently cultivated, owing to conflict, farming techniques, lack of infrastructure, and government indifference toward developing the sector. As a result, the country is highly dependent on food imports from Uganda, Kenya, and Sudan.

Massive Displacement

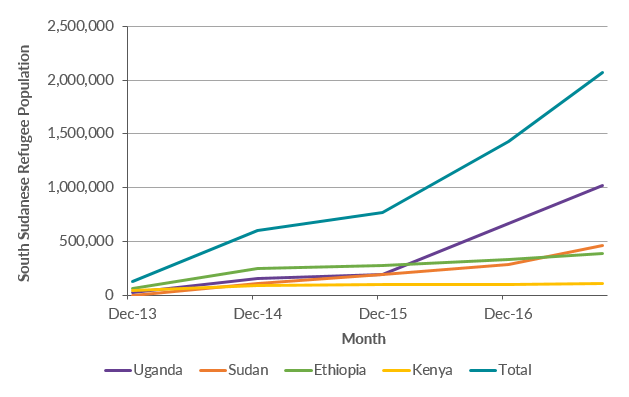

This toxic mix of conflict and drought—and ensuing famine—has resulted in the displacement within the country of nearly 1.9 million people, with 2 million others having fled, mainly to Ethiopia, Kenya, Sudan, and Uganda (see Figure 1). In Uganda alone, the number of South Sudanese refugees surpassed the 1 million mark in August 2017. About 200,000 civilians have also taken shelter at UN-protected sites in government-controlled towns.

Figure 1. Top Host Countries for South Sudanese Refugees, 2013-17

Source: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “South Sudan Situation: Information Sharing Portal,” accessed October 11, 2017, available online.

Natural disaster and conflict can combine to influence displacement in a number of ways. When severe climate conditions strike countries already experiencing conflict, the combined pressures on the population can lead to greater displacement. Disasters can also contribute to or exacerbate violent conflict, as dwindling water supplies and pasture land create outbreaks of violence between and among pastoralists and local communities. This has all been the case in South Sudan.

Countries receiving the large influx of South Sudanese and their livestock have seen new strains placed on their already-stretched resources, particularly water and pasture land. More animals watering has led to conflict between pastoralist communities and farmers. Refugee and internally displaced person (IDP) camps are often overcrowded, have poor sanitation, and lack clean water, allowing communicable diseases such as cholera to spread rapidly.

Further, most South Sudanese refugees are women and children. Roughly 62 percent of the refugee population is under age 18 and about half of the 984,000 school-aged children were out of school as of September 2017, disrupting their learning and growth. Lack of resources, including supplies and teachers, hinders their integration into host-country education systems. Refugee children are also vulnerable to abduction or recruitment by armed groups. As of May 2017, more than 75,000 unaccompanied and separated children in total had entered Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia.

Uganda

Uganda hosts the fifth-largest refugee population in the world and the largest in Africa, including the largest share of South Sudanese refugees: more than 1 million, of whom 85 percent were women and children.

Uganda has won praise from the international community for its progressive refugee policies, which promote self-reliance and peaceful coexistence with local communities. Under Uganda’s 2006 Refugee Act, refugees are allocated small plots of land in local villages to use for shelter and agriculture, and are able to work, start businesses, and move relatively freely around the country. Refugees also have access to free health-care services and primary and secondary education.

However, lack of adequate resources and funding amid the surge in refugee arrivals has meant the implementation of these policies remains challenging for Uganda. A World Food Program (WFP) budget shortfall has led to cuts in rations for refugees. Ugandan authorities have struggled to find enough land for the growing numbers of refugees, and have been forced to reduce the size of plots. Further, enrolling children in school remains out of reach for some refugee families, owing to school-related expenses, language barriers, and other obstacles.

Ethiopia

Since the start of South Sudan’s civil war, hundreds of thousands of South Sudanese refugees have arrived in the Gambella region of Western Ethiopia. More than 19,000 unaccompanied and separated children had entered as of June 2015, some with traumatic experiences.

Ethiopia is a leader in the South Sudanese mediation process. Along with the Anyuak, the Nuer are one of two main ethnic groups in Gambella, and are sympathetic to their kinsmen fleeing persecution in South Sudan. However, the security situation in Gambella is fragile, and violent incidents have broken out between the Anyuak and Nuer, a cascading effect of the refugee influx. Thus, Ethiopia is careful not to take sides in the conflict to avoid further internal tensions in border communities.

Ethiopia has also worked to strengthen its existing supports for refugees. It plans to expand its policy allowing some refugees to live outside of camps, offer work permits and land to refugees, and increase refugee enrollment in schools. With the help of international donors, Ethiopia is also building industrial parks that will employ 100,000 people, reserving about 30 percent of the jobs for refugees.

Other Top Refugee Hosts

Elsewhere in the region, large numbers of South Sudanese have also fled to the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Kenya, and Sudan. As many newly arrived refugees in these countries are in isolated and unsafe locations, aid workers have found it difficult and dangerous to reach them with humanitarian aid. The vast majority of the new arrivals are school-aged children, necessitating protection from abuse, sexual assault, and forced recruitment by armed groups.

Kenya, which has long hosted hundreds of thousands of refugees from around the region, has pioneered a new approach in response to the South Sudanese influx. With the backing of UNHCR and the World Bank, it launched the Kalobeyei Integrated Social and Economic Development Program, establishing a settlement in Turkana County, near the border with South Sudan. With implementation planned through 2030, the program aims to improve livelihood opportunities and socioeconomic conditions for refugees and host communities, while reducing reliance on humanitarian aid over the long term. However, lack of funding has emerged as a serious limitation, aggravated by a drought that has hit Turkana’s largely pastoralist economy hard.

Meanwhile, few South Sudanese have been resettled abroad or sought asylum outside the region. From the start of the war through 2016, slightly more than 600 asylum applications were filed by South Sudanese in Europe, and in fiscal year (FY) 2015 the United States resettled just 79 refugees from South Sudan. Several factors explain the lack of interest in onward migration, including unfamiliarity with urban living, low levels of education, the predominance of women and children, lack of financial resources, and a deep cultural commitment to and pride in their homeland—particularly after a long struggle for independence.

Responses by Civil Society and the International Community

Because the crisis in South Sudan is the result of many intertwined factors, concerted action from civil society as well as governments and international organizations will be needed to bring an end to the humanitarian disaster.

Several strategies at local, regional, and international levels have been attempted, but they have been unable to end the violence and reconcile warring factions. In August 2015, a peace deal was agreed to amid intense international pressure and the threat of sanctions. The Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan eventually brought Machar, who had fled to South Africa, back to Juba in April 2016 with a sizeable security force. However, clashes erupted again in August 2016, owing in part to the fact that the agreement mandated the two warring parties (rebel forces led by Machar, and the government) share power in Juba while maintaining separate military forces. The war continues to expand, marked by growing divides among ethnic fault lines.

In terms of regional responses, a bloc known as the Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), currently chaired by Ethiopia, has taken the lead in mediating a political solution to the conflict. It has also coordinated the humanitarian efforts of East African countries through its Drought Disaster Resilience and Sustainability Initiative.

At the international level, the United States donated more than $518 million in fiscal year (FY) 2017 to relief efforts in South Sudan, bringing total U.S. contributions since the start of the conflict to nearly $2.7 billion—the most of any international donor. The United States has also placed sanctions on members of Kiir’s inner circle, pointing to the role of government officials in perpetuating the conflict. Meanwhile, the European Commission has contributed $117 million, and in September 2017, the World Bank donated $50 million to combat hunger and malnutrition in South Sudan.

Several humanitarian organizations have been working on the ground to prevent future outbreaks of famine. The World Food Program assisted 4 million people in 2016, deploying rapid-response teams to remote parts of the country to deliver food aid. Oxfam International has provided food, water, and sanitation services to hundreds of thousands of people. However, the humanitarian response to South Sudanese refugees is one of the most expensive in the world, and has been hampered by severe funding shortfalls. As of August 2017, just 28 percent of UNHCR funding needs for South Sudanese had been met, leaving a gap of $633.4 million.

Beyond the challenge of reaching some parts of the country, the situation is becoming more dangerous for aid workers, who are often harassed and find their supply compounds looted or vandalized. Eighty-two humanitarian workers have been killed in South Sudan over the last three years.

No End in Sight?

With the conflict dragging on and no durable end in sight, there is a need for longer-term solutions, both on mediating a political end to the violence, as well as for the millions living in displacement and facing chronic food shortages.

To better support those living in long-term displacement, neighboring countries could implement a multifaceted response that including access to primary health care, basic education, and employment. Due to the sheer size of the refugee flows, funding shortfalls and capacity limitations constrain refugee service provision in practice, even for relatively generous Uganda and Ethiopia. In terms of ending the conflict, implementation of the 2015 peace agreement has stalled, and the United Nations has questioned whether IGAD and the international community will be able to show a “unity of purpose” in support of lasting peace. Ultimately, it will take concerted coordination among national, regional, and international actors to contain and prevent future violence and a new exodus of refugees.

Sources

ACAPS. 2017. ACAPS Briefing Note: Food Security and Nutrition in South Sudan. Geneva: ACAPS. Available online.

African Union (AU). 2017. African Union: News Highlights. News release, AU, April 20, 2017.

---. 2017. African Union: News Highlights. News release, AU, May 1, 2017.

---. 2017. African Union: News Highlights. News release, AU, May 3, 2017.

---. 2017. African Union: News Highlights. News release, AU, May 9, 2017.

---. 2017. African Union: News Highlights. News release, AU, May 18, 2017.

Aizenman, Nurith. 2017. Who Declares a Famine? And What Does That Actually Mean? NPR, February 23, 2017. Available online.

Barigaba, Julius. 2017. Shrinking Land Opens New Challenge Facing South Sudanese Refugees. EastAfrican, September 10, 2017. Available online.

Concern Worldwide. 2015. Consequences of Conflict: Coping with Hunger in South Sudan. Blog post, October 12, 2015. Available online.

Devi, Parveen. 2017. Drought and Conflict in South Sudan Fuelling the World’s Fastest Growing Refugee Crisis. World Vision, March 24, 2017. Available online.

Dhala, Khairunissa. 2017. The World Has Abandoned South Sudanese Refugees. Al Jazeera, June 21, 2017. Available online.

Disasters Emergency Committee (DEC). 2017. DEC Warns of Toxic Mix of Drought and Conflict in South Sudan Fuelling the World’s Fastest Growing Refugee Crisis. Press release, DEC, March 24, 2017. Available online.

Economist. 2017. How is Famine Declared? Economist, April 4, 2017. Available online.

European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (EU ECHO). 2017. ECHO Factsheet – Horn of Africa. Brussels: EU ECHO.

Ferguson, Jane. 2017. 20 Million Starving to Death: Inside the Worst Famine Since World War II. Vox, June 1, 2017. Available online.

Frouws, Bram. 2016. Out of Sight, out of Mind: Why South Sudanese Refugees Are Not Joining Flows to Europe. Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat, June 14, 2016. Available online.

Gebrekidan, Getachew Z. 2016. Bloodshed in South Sudan: The Risk of Spiraling Into Genocide. Washington, DC: Wilson Center Africa Program.

Hattem, Julian. 2017. Uganda May Be Best Place in the World to Be a Refugee. But That Could Change without More Money. Washington Post, June 20, 2017. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2017. Urgent Action Needed to Help Millions Facing Famine in South Sudan, Somalia, Yemen, North-east Nigeria. News release, IOM, February 28, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. IOM South Sudan Humanitarian Update #78. IOM, September 15, 2017. Available online.

Kolmannskog, Vikram. 2009. Climate Change, Disaster, Displacement and Migration: Initial Evidence from Africa. New Issues in Refugee Research, Paper No. 180. Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available online.

Migration Policy Institute (MPI) Data Hub. N.d. Asylum Applications in the EU/EFTA by Country, 2008-2016. Accessed October 11, 2017. Available online.

Morello, Carol. 2017. U.S. Sanctions South Sudan Officials for Allegedly Enriching Themselves Amid Civil War, Famine. Washington Post, September 6, 2017. Available online.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Centers for Environmental Information. 2017. State of the Climate: Global Climate Report for Annual 2016. Available online.

Oxfam International. N.d. Famine in South Sudan: Communities at Breaking Point. Accessed October 11, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. Hungry in a World of Plenty: Millions on the Brink of Famine. Accessed October 11, 2017. Available online.

Regional Mixed Migration Secretariat (RMMS). N.d. Regional Mixed Migration in East Africa and Yemen in 2017: 1st Quarter Trend Summary and Analysis. Accessed October 11, 2017. Available online.

Scalabrini Migration Study Centers. 2017. International Migration Policy Report. New York: Center for Migration Studies of New York. Available online.

Small Arms Survey. 2017. Spreading Fallout: The Collapse of the ARCSS and New Conflict Along the Equatorias-DRC Border. Geneva: Small Arms Survey. Available online.

UN Environment Program (UNEP). 2017. New Nation, New Famine. UNEP, April 11, 2017. Available online.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2017. Number of Refugees Fleeing South Sudan Tops 1.5 Million. News release, UNHCR, February 10, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. South Sudan Situation 2017. Geneva: UNHCR. Available online.

---. 2017. South Sudan Situation: Information Sharing Portal. Updated October 1, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. The Plight of South Sudanese Refugee Children - Reflections of the Regional Refugee Coordinator. News release, UNHCR, September 20, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. More Than One Million Children Flee South Sudan Violence. News release, UNHCR, May 8, 2017. Available online.

UNICEF. 2015. Ethiopia: South Sudanese Refugees’ Update. UNICEF, June 2015. Available online.

---. 2017. Regional South Sudan Refugee Situation For Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda. UNICEF, August 31, 2017. Available online.

U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). 2017. South Sudan - Crisis. Fact sheet, USAID, September 1, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. South Sudan. Updated September 13, 2017. Available online.

U.S. State Department Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration. 2016. Proposed Refugee Admissions for Fiscal Year 2017. Updated September 15, 2016. Available online.

Wainaina, Stephen. 2017. Droughts in East Africa Becoming More Frequent, More Devastating. African Arguments, March 17, 2017. Available online.

Wood, Tamara. 2015. Human vs ‘Natural’ Causes of Displacement: the Relationship between Conflict and Disaster as Drivers of Movement. Nansen Initiative, May 27, 2015. Available online.

World Food Program (WFP). N.d. South Sudan Emergency. Accessed October 11, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. World Bank Donates US $50 Million to Fight Hunger and Malnutrition in South Sudan. News release, WFP, September 12, 2017. Available online.