You are here

Stateless and Persecuted: What Next for the Rohingya?

Ramshackle dwellings dot a hillside in the Kutupalong refugee camp, outside Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. (Photo: Kathleen Newland)

People of the Rohingya ethnic group have been described by the United Nations and others as the world’s most persecuted minority, a phrase that is a poor substitute for the personal histories of loss, deprivation, and displacement experienced by more than 2 million people. Their status is due to a long history of discriminatory and arbitrary laws, policies, and practices that have deprived and denied Rohingya people from obtaining citizenship in their native Myanmar (also known as Burma), complicated their access to asylum abroad, and subjected them to a wide array of rights violations and persecution.

UN-appointed independent factfinders have found that the Myanmar military’s indiscriminate violence against the Rohingya, which has included brutal tactics such as burning villages, torture, and sexual violence, may amount to genocide. Members of the Rohingya community, rights groups, and a range of international officials including the U.S. House of Representatives have all concluded a genocide took place. And the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which is in the process of reviewing genocide allegations against Myanmar, has ordered the country to comply with measures to safeguard the Rohingya.

These efforts were complicated by the Myanmar military’s February 2021 coup, and it remains to be seen how this development will impact wider efforts to protect Rohingya rights and pursue accountability for alleged international crimes. The military and Myanmar’s hitherto civilian-led government, under the de facto leadership of Aung San Suu Kyi, had previously presented a unified front on the Rohingya issue, with Suu Kyi even appearing on behalf of the Myanmar delegation before the ICJ. The coup, however, immediately resulted in a deep schism between the military and the civilian government, as evidenced by Suu Kyi’s deposing and arrest. It also may lead to changing public attitudes towards the Rohingya and military, as the general public—whose sentiment had been largely against the Rohingya—experiences firsthand the junta’s strongarm tactics in cracking down on anti-coup protests.

Rohingya refugees in neighboring Bangladesh have said the coup raised their anxieties about return, seeming to further complicate a new effort to repatriate hundreds of thousands of Rohingya to Myanmar later in 2021. Bangladesh’s previous attempts at repatriation have failed, amid opposition from many Rohingya who feared renewed persecution upon return. In the meantime, thousands of refugees have been controversially relocated by the Bangladeshi government to a remote island in the Bay of Bengal, effectively detained in conditions that may amount to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment. Hundreds of thousands remain crowded into ramshackle refugee camps around Cox’s Bazar.

This article reviews the series of strategic decisions and policies that have flipped the Rohingyas’ world upside down by rendering them largely stateless and vulnerable to abuse. It briefly introduces who the Rohingya are, the conditions of their statelessness, what they have endured in Myanmar, and their situation as asylum seekers and refugees internationally.

The Rohingya in Myanmar

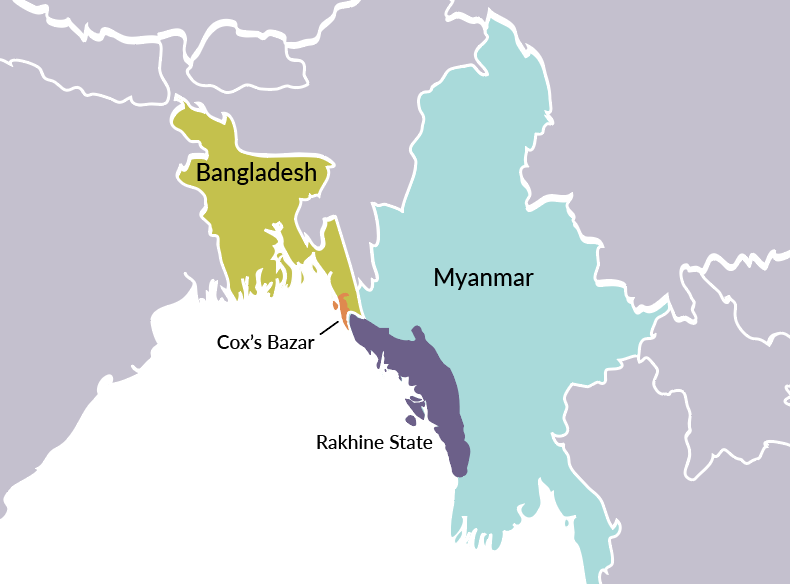

The Rohingya are an ethnic community from Rakhine State, in the west of Myanmar, bordering Bangladesh. Their histories in the area far predate modern state borders, which emerged in the 20th century amid Myanmar’s separation from British India and later independence from the United Kingdom. Yet members of the ethnic group, who are predominantly Muslim, have been denied citizenship in Buddhist-majority Myanmar for more than four decades.

At the start of 2017 there were approximately 1 million Rohingya in Myanmar, a country of 54 million; hundreds of thousands subsequently fled following a wave of violence from state security forces, who consider the Rohingya to be irregular migrants from Bangladesh. As of late 2020 there were reportedly more than 1 million Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh and hundreds of thousands in India, Malaysia, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, and countries farther afield.

Figure 1. Map of Bangladesh and Myanmar

The Myanmar government’s large-scale deprivation and denial of Rohingyas’ citizenship has been a central component of this population’s persecution. Over the course of decades, Myanmar has arbitrarily stripped the nationality of and imposed statelessness on the Rohingya, facilitating serious violations on their rights including the right to work and access education. Rohingya activists, journalists, and human-rights advocates have documented cases in which security forces engaged in systematic killings, rapes, and destruction of entire villages. The policies have been part of a broader strategy by the government of Myanmar, which has struggled to consolidate legitimacy from a range of ethnic groups, that Rohingya advocates believe violates Article 11 of the 1948 Genocide Convention forbidding “deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.”

Myanmar’s 1982 Citizenship Law is the central legal instrument behind Rohingyas’ statelessness, implemented in a manner that particularly targets the Rohingya community. Their stateless condition has reinforced the state’s narrative that they are foreigners—or, in the government’s terminology, “illegal immigrants”—who are unworthy of state protection. Officially, most Rohingya are not citizens of Myanmar but “resident foreigners.” As such, the Rohingya are positioned as a group with no history or connection to their country. Powerful nationalist voices outright deny that there is such a thing as a Rohingya ethnic group, and instead refer to them as “Bengali.”

Stateless Citizens

Our citizenship has been stolen from us. Rohingya statelessness is not an accident of history, it was deliberately produced by the Myanmar military as a part of the ongoing genocide.

— Nay San Lwin

Most Rohingya are, as Article 1 of the 1954 Convention on Statelessness defines the concept, “not considered as a national by any state under the operation of its law.” As with refugees, international legal frameworks entitle stateless individuals to protections and legal status in third states. However, being defined as stateless has brought few tangible protections to the Rohingya—in fact, it has often been to their detriment.

Before the events of 2017, few UN agencies, diplomatic missions, and humanitarian organizations embraced the word “Rohingya,” which was not recognized by the Myanmar government. When combined with the recognition of their statelessness, this fed into the state’s inaccurate narrative that the Rohingya ethnicity did not exist, and that Rohingya people were foreign to Myanmar. This led to an erosion of trust between the Rohingya community and international actors. This was further exacerbated by the significant leeway that much of the world afforded Myanmar under Suu Kyi, a democracy advocate and Nobel Peace Prize winner whose international reputation declined over her government’s treatment of the Rohingya, even as rights groups raised early warnings of its genocidal intent.

What the Rohingya are left with is a status that reinforces the lie that they are not from Myanmar. Many Rohingya, for their part, reject being identified as stateless, claiming instead that they are (or should be) Myanmar citizens—a position on which many legal experts agree.

This is why it is important to view the Rohingyas’ statelessness as a consequence of the arbitrary and discriminatory deprivation of their nationality, and to affirm their right to nationality as a central part of any solution going forward. Under provisions such as Article 15 of the landmark Universal Declaration of Human Rights, every person has the right to a nationality, and no one should be arbitrarily deprived of their nationality. The Rohingyas’ statelessness is a result of being denied this fundamental human right, and with it the claim to Myanmar citizenship.

Myanmar has suffered few repercussions for stripping the Rohingya of their nationality. Many in the Rohingya community will likely continue to refuse to identify as stateless until there is stronger global emphasis on Myanmar’s obligation to restore their nationality rights.

Documented but Not Authorized

Being denied citizenship is not the same as being denied documentation altogether. Indeed, the Rohingya in Myanmar over decades have been issued multiple forms of documentation. However, these documents have largely served to further marginalize their position in Myanmar’s civic body.

The primary proof of residency and birth for a Rohingya person in Myanmar is through a paper-based household registration or “family list” system. The system applies to all residents of Myanmar but has largely been used as a tool to control minority ethnic groups. These lists are regularly checked and updated as part of immigration enforcement and state surveillance activities. They record identity card numbers, religion, and ethnicity. Through them, Myanmar authorities have closely surveilled the Rohingya for decades, at times and in different areas controlling their movement, ability to marry, the number of children they could have, and other aspects of life.

In addition to the family list, Rohingya people have been required time and again to surrender their documents in exchange for new paperwork that places them in inferior positions. After the 1982 Citizenship Law came into force, Rohingya with National Registration Cards (which had been issued under the post-independence 1949 Residents of Myanmar Registration Act) were required to surrender them, and with it their best chance at being able to claim citizenship. Those few who were able to obtain naturalized citizenship—one of the three categories of citizenship outlined by the 1982 law—were labelled as Bengali, which carried negative and racist connotations. Subsequently, between 1995 and 2015 many Rohingya were issued Temporary Registration Cards that explicitly stated no citizenship was conferred—further reinforcing the narrative of Rohingya people as foreigners. The cards, which were white (as opposed to blue, green, and pink cards given to citizens) often referred to the Rohingya as Bengali. In 2015 these cards were nullified, preventing Rohingya from voting in national elections and requiring them to go through a new round of documentation and vetting processes. The National Verification Cards (NVC) in place since are for individuals who are not recognized as citizens. In practice, they are mostly issued to Rohingya and members of other Muslim groups. Rohingya groups have linked the NVC to mass expulsions and genocide, and feel that, by entrenching the notion of their foreignness, the cards are a trap to bar them from accessing citizenship.

Rohingya advocates and human-rights groups have criticized foreign governments and international organizations for their participation in processes that have assisted these documentation schemes. For example, Myanmar’s 2014 national census required Rohingya people to identify as Bengali, leading many to refuse to participate and therefore go uncounted. Financial and logistical support for the census was provided by the United Nations and the governments of Australia, multiple European countries, and the United States. More recently, a smartphone app developed with assistance from the European Union-funded STEP Democracy project aimed to provide information about candidates in Myanmar’s November 2020 general election, yet was widely denounced for using contextually derogatory ethnic identifiers that listed Rohingya candidates as Bengali. The organization responsible for implementing STEP Democracy, International IDEA, subsequently withdrew its support for the app. The UN special envoy on Myanmar also has been criticized by rights advocates for suggesting that Rohingya “consider applying for registration” under the NVC process. Furthermore, the Myanmar government’s plans to digitize identity documents, which have been piloted with international corporations, could lead to further entrenching the group’s exclusion and persecution. Advocates’ concern is that, without reform to the underlying discriminatory and arbitrary legal framework, layering on top a digital identification system will ultimately do more harm.

Outside Myanmar: Asylum Seekers without Protection

In 2017, Myanmar security forces and nationalist mobs conducted a violent campaign against the Rohingya population in North Rakhine State, razing villages, killing large numbers of people, and dumping their bodies in mass graves. Hundreds of thousands subsequently fled to Bangladesh and other countries. These were perhaps the most shocking and brutal atrocities to have been committed against the Rohingya, but they were not the first.

Activists and rights groups have documented systemic persecution and genocidal acts against the Rohingya for more than four decades. Dramatic escalations in 1978, 1991, 2012, and 2016 all were followed by mass exoduses of Rohingya to other countries—mostly Bangladesh. Yet the asylum protections they have received have often come up short. In 1978-79, approximately 180,000 Rohingya were repatriated from Bangladesh to Myanmar; an estimated 10,000 more died in Bangladesh due to malnutrition and related ailments. Between 1993-95, approximately 200,000 Rohingya were returned to Myanmar through a process that members of the community and aid workers have subsequently described as coercive. Amid the 2012 flight, more than 1,000 Rohingya asylum seekers were reportedly pushed back at the Bangladesh border, in violation of the fundamental international law principle against refoulement.

Bangladesh is not a party to the 1951 Refugee Convention and does not have a national framework in place to protect refugees. Neither do India, Malaysia, or Saudi Arabia, which also host large Rohingya populations. As such, Rohingya refugees have often been criminalized and treated as irregular immigrants, leaving them with ambiguous legal status; extremely vulnerable to crackdowns, deportations and arbitrary detention; and restricted in their ability to legally work, access education, health care, and other social benefits. This situation has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, more than 850,000 Rohingya live in a massive collection of refugee camps—including Kutupalong, often regarded as the largest camp in the world—as of the start of 2021. The majority arrived following the violence of 2017, but others have lived in Bangladesh for decades. Tens of thousands were born in Bangladesh but do not qualify for Bangladeshi citizenship, despite Article 7 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which Bangladesh has ratified, protecting every child’s right to a nationality “in particular where the child would otherwise be stateless.”

Under a joint registration process between the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Bangladeshi government, the Rohingya are registered not as refugees but as “Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals,” a term which fails to recognize their stateless status. The UN system refers to these people as refugees, but the official registration nonetheless prevents them from enjoying the full rights that would come with this status.

Bangladesh and Myanmar have attempted to repatriate large numbers of the Rohingya at multiple points since the 2017 flight—including a planned effort in 2021, to which Burmese military leaders have recommitted in the wake of the coup—but the efforts have so far largely come to naught. Myanmar, UNHCR, and the UN Development Program agreed on a memorandum of understanding regarding the circumstances of repatriation in 2018, and twice renewed it in 2019 and 2020. Many Rohingya in Bangladesh have opposed repatriation under current circumstances, saying they were not consulted on the agreement and demanding recognition of their right to Myanmar nationality as a condition for repatriation. Officials in Bangladesh, one of the most densely populated countries in the world, have said the country is overwhelmed with the Rohingya population that has emerged in the Cox’s Bazar area. However, the government has declined to restart a resettlement program it halted in 2010, which would have facilitated the resettlement of many Rohingya refugees to countries including Australia, Canada, and the United States.

Of additional concern is the relocation of Rohingya in Bangladesh from refugee camps to the flood-prone silt island Bhasan Char. The first 1,600 refugees were moved to the island in December 2020, despite concerns that it was not suitable for habitation and allegations that many Rohingya were brought there against their will. Other relocations followed in subsequent weeks. The Bangladesh government has sought for years to eventually relocate 100,000 Rohingya onto the isolated island, a process that has not involved the United Nations. Advocates and human-rights groups have raised concerns that the relocation will significantly restrict Rohingyas’ liberty and movement and leave them in conditions that may amount to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

A closer look at India and Malaysia shows that many Rohingya face similar challenges there as well. Many have been denied protections and access to UN officials. As they make their dangerous journeys, often via sea, many asylum seekers are also easy pickings for smugglers and traffickers who hold them in chattel-like conditions on boats. For instance, in February 2021 a boat of 90 Rohingya refugees was stranded off the coast of the Andaman Islands; eight reportedly died before the group was rescued by India’s coast guard, which attempted to return the survivors to Bangladesh.

Rohingya activist Ali Johar said in 2020:

We are survivors of genocide, but we are victim-blamed for making dangerous journeys to find security for our families. If Rohingya people had access to decent livelihoods and education and were able to move legally, there would be no incentive for us to turn to traffickers. The best way to combat exploitation is to provide us with the legal means to live in dignity.

International Denial of Rights

Myanmar’s treatment of the Rohingya has been roundly scrutinized, but their treatment as asylum seekers in other countries deserves equal analysis. Other states’ denial of the Rohingyas’ rights to work, to study, and to access health care is notable. On numerous occasions, governments in Dhaka and elsewhere have expressed wariness to offer greater protections, on the grounds that doing so would encourage more Rohingya to come to their shores. As a result, states have seemingly raced to present themselves as the least attractive destination.

Rohingya advocates call this argument flawed, dismissing that a pull factor can exist when one is fleeing genocide. Moreover, states’ obligations to protect individuals’ human rights cannot be waved away due to concerns about attracting more asylum seekers.

Any real solutions to the Rohingya situation, advocates claim, will only be possible if global governments and international organizations prioritize human rights in both foreign and domestic policy, rather than simply as negotiating leverage weighed against geopolitical and economic considerations.

Visibly Invisible?

Due to the magnitude of the atrocities they have faced, the Rohingya are among the most visible victims of persecution worldwide. Their visibility, however, has not brought with it enough robust action to restore their rights any time soon. The Gambia, with the backing of the 57-member Organization for Islamic Cooperation, has initiated ICJ proceedings regarding allegations that Myanmar violated provisions of the Genocide Convention. But that process is likely to take several years to conclude. Canada and the Netherlands signaled their intent to intervene in the case in September 2020, but many powerful countries including others in the European Union, the United Kingdom, and the United States have yet to sign on.

The International Criminal Court has also opened an investigation into possible crimes against humanity in Myanmar, specifically the forced deportation of more than 740,000 Rohingya people into Bangladesh in 2017. But the UN Security Council has not held a meeting on the situation since February 2019 and has not issued a formal document on it since November 2017. Meanwhile, the United States, the European Union, and other global powers have levied sanctions against Myanmar officials—including in the wake of the coup—but they have had little effect in changing the Rohingyas’ status.

So while the ethnic group may have gained visibility, the rights of the Rohingya have not been advanced in any meaningful or tangible way. Rohingya activists and human-rights advocates have long pushed for change during the decades in which the Rohingyas’ world has been turned upside down. The opinions and demands of the Rohingya community, which were largely unheard prior to 2017, have since become more visible. However, the world’s most persecuted people are yet to see concerted action for a lasting resolution. Is their situation likely to change? In the near term it seems difficult to imagine how.

Sources

Adams, Brad. 2019. For Rohingya, Bangladesh’s Bhasan Char ‘Will Be Like a Prison.’ Blog post, Human Rights Watch, March 14, 2019. Available online.

Brinham, Natalie et al. 2020. Locked In and Locked Out: The Impact of Digital Identity Systems on Rohingya Populations. Briefing paper, Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion, London, November 2020. Available online.

Burma Campaign UK. 2019. UN Special Envoy Should Drop ‘Appalling’ Support for NVC Process. Press release, January 31, 2019. Available online.

Crisp, Jeff. 2018. 'Primitive people': The Untold Story of UNHCR's Historical Engagement with Rohingya Refugees. Humanitarian Practice Network. October 2018. Available online.

Doctors Without Borders. 2017. MSF: At least 6,700 Rohingya Killed during Attacks in Myanmar. Press release, December 14, 2017. Available online.

Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion. 2020. Human Rights and COVID-19: What Now for The Rohingya? Briefing paper, Institute on Statelessness and Inclusion, London, August 2020. Available online.

Lwin, Nay San. 2019. Comments at the World Conference of Statelessness and Inclusion. The Hague, June 26-28, 2019

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2020. UNDP, UNHCR and the Government of the Union of Myanmar Extend Memorandum of Understanding. Press release, May 11, 2020. Available online.

---. N.d. Refugee Response in Bangladesh: Population Figures. Last updated December 31, 2020. Available online.

UN Human Rights Council. 2019. Detailed Findings of the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar, A/HRC/42/CRP.5. Geneva: UN Human Rights Council. Available online.

UN News. 2017. UN Human Rights Chief Points to ‘Textbook Example of Ethnic Cleansing’ in Myanmar. UN News, September 11, 2017. Available online.

Potter, Richard and Kyaw Win. 2019. National Verification Cards: A Barrier to Repatriations. London: Burma Human Rights Network. Available online.

Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Immigration and Population, Department of Population. 2015. The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census: The Union Report, Census Report Volume 2. Nay Pyi Taw: Department of Population. Available online.

Win, Pyae Sone and Grant Peck. 2020. Ethnic Identifiers in Myanmar Election App Criticized. Associated Press, October 1, 2020. Available online.