Time to Temper the Faith: Comparing the Migration and Development Experiences of Mexico and Morocco

Versión español | Version française

Over the second half of the 20th century, Mexico and Morocco have evolved into main sources of predominantly low-skilled migrant labor in the United States and the European Union, respectively.

Despite large historical, cultural, and economic differences, these two countries share the geopolitical feature of being located on the globe's main South-North divides and "migration frontiers." This explains the striking similarities between Mexican and Moroccan migration trends.

About 10 percent of Moroccan and Mexican citizens live abroad, and in both countries, remittances have become a vital source of income and poverty alleviation, particularly in rural areas.

In view of the strategic importance of migration, it is not surprising that both the Moroccan and Mexican governments have openly or tacitly encouraged emigration and have recently intensified efforts to foster ties with their emigrant populations to maximize remittance flows and to boost the positive development impact of migration.

Although optimistic views on migration and development have surged recently, this issue remains contested.

Given their remarkable similarities in terms of the relative magnitude of emigration and its strategic economic importance, it is striking that Morocco and Mexico have rarely been systematically compared; indeed, existing comparisons have generally focused on border issues.

To fill this gap, in 2008 the International Migration Institute of the University of Oxford initiated the project Transatlantic Dialogues on Migration and Development Issues: The Mexico-U.S. and Morocco-EU Experiences in close collaboration with Mexican and Moroccan researchers and policymakers (see sidebar for details).

This article briefly examines the migration history of each country, the drivers of migration, remittance trends, the effects migration has had on development, and the experiences of migrant associations and collective remittances. Based on evidence from the project, it then looks at ways to reframe the debate over migration and development.

|

Project Background

|

||

|

Morocco and Mexico as "Migration Frontier" Countries

While Mexico-U.S. and Morocco-EU migration flows have deep historical roots, it is particularly since the 1950s and 1960s that Mexico and Morocco evolved, in progressive phases, into labor sources for the booming American and northern European economies.

Migration increased largely due to labor-recruitment schemes. In the United States, millions of Mexicans came through the Bracero program, which started during World War II. The program (1942 to 1964) funnelled workers to mainly temporary jobs in agriculture.

In Europe, several northwest European countries (France, Netherlands, Belgium, Germany) signed bilateral agreements with Morocco in the 1960s to bring over "guest workers" to fill jobs in factories, mines, agriculture, and construction. Most of these agreements were discontinued in 1973 or shortly thereafter due to the oil crisis, when fuel prices rose dramatically worldwide due to an embargo by oil-producing states in the Middle East.

In both cases, postrecruitment freezes and return migration policies did not lead to massive return.

Instead, migration restrictions interrupted the back-and-forth movement known as circular migration and paradoxically boosted permanent settlement and family migration in the 1980s. Extensive Mexican and Moroccan networks encouraged migrants' family and friends to join them; many crossed their respective border illegally.

By 2008, there were an estimated 11.4 million Mexican-born U.S. residents according to the U.S. Census Bureau's annual American Community Survey, over half of them unauthorized according to estimates from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. A 2007 report from the Hassan II Foundation for Moroccans Residing Abroad estimated that Morocco had about 3.2 million citizens abroad, 2.75 million of which were in the European Union; the unauthorized are particularly concentrated in southern Europe, where estimates reach at least 200,000 individuals.

Since the 1990s, the destinations and origins of both Mexican and Moroccan migration have become more diverse.

Mexican migrants, though still concentrated in the classic destination states of California, Texas, and Illinois, have followed economic opportunities in southern states like Georgia and North Carolina and central states like Iowa and Nebraska. While Mexican emigrants usually came from central-western states like Guanajuato, Jalisco, Zacatecas, and Michoacan, flows now include those from southern and southeastern Mexican states, such as Chiapas, Oaxaca, and Veracruz.

For Moroccans, Spain and Italy became new destinations as it was relatively easy for unauthorized immigrants to find work. Also, more women left Morocco and found jobs as domestic workers and nannies. Higher-skilled Moroccans have increasingly migrated to the United States and Canada.

While most Moroccans traditionally migrated from the northern Rif mountains, the southwestern Sous region, and southern oases, increasing migration to Spain, Italy, and North America has coincided with the rise of several new source regions in central Morocco, such as the Tadla plain and Khouribga, as well as big cities.

Over the last 20 years, both Mexico and Morocco have experienced increasing transit and even settlement migration from poorer countries located further south in Central American and sub-Saharan countries, respectively. Because of their role as "transit" countries, the United States has pressured Mexico and the European Union has pressured Morocco to better enforce their own borders and to accept deportees from countries in their respective regions.

Migration Drivers: North-South Gaps

Migration from Mexico and Morocco is closely associated with business cycles in the United States and the European Union, according to a background study for this project. Emigration rates declined during the recession of the early 1980s then rose in the 1990s due to strong economic growth and economic and labor market deregularization in the United States and the European Union.

The global economic crisis, which hit industries like construction that employed many immigrants, drove up unemployment among Mexican and Moroccan migrants and likely affected new inflows. In Spain, the unemployment rate for the construction sector peaked at 19.6 percent in May 2009.

After going as high as 14.6 percent in January 2010, the unemployment rate for Mexican and Central American immigrants in the United States dropped to 9.5 percent in May 2010. Also, fewer people appear to be heading north. According to a monthly household survey that the Mexican government conducts, the number of people leaving to go abroad was down 8 percent in the third quarter of 2009 compared to the same period in 2008 and 39 percent less than the same period in 2007.

It is unclear when and how quickly immigration rates will resurge as a result of improving economic conditions and job opportunities. What has become clearer is that similar to the 1970s, the recession has not caused the majority of migrants to go home.

Mexican and Moroccan migration flows respond to the persistent demand for cheap and low-skilled labor in agriculture, construction, and service sectors. In addition, increasing economic integration, mainly through investments and free-trade agreements between the United States and Mexico (North American Free Trade Agreement) and the European Union and Morocco (EU Association Agreements), has continued to fuel (often illegal) migration.

Both the United States and the European Union invest heavily in "combating" illegal migration, but neither has adequately addressed the demand for low-skilled labor. Consequently, migration restrictions and severe border controls have actually increased illegal migration, changed the routes migrants use, made migration riskier, and decreased circulation.

The analysis also showed that Mexico-U.S. and Morocco-EU income gaps have remained remarkably constant since the 1980s despite (or, according to some project participants, as a result of) free-trade agreements (see Figure 1). The Morocco-EU income gap of 1:9 is much higher than the Mexico-U.S. income gap of 1:3.5. However, income inequality within Mexico is higher than in Morocco, which helps explain why many Mexicans head north.

At the same time, the gap in several human development indicators, such as life expectancy, have nearly closed. Birth rates in Mexico and Morocco have dramatically slowed while literacy rates have gotten closer to the levels in the United States and the European Union (see Table 1). However, whether these trends will eventually lead to declining emigration and increasing immigration will crucially depend on future economic growth and political stability.

|

|

||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Remittances Trends and Remittance Dependency

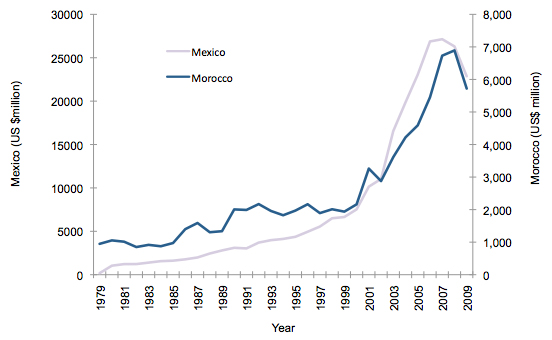

Remittances to Mexico and Morocco have grown rapidly over the past decades, due to growing populations abroad, expanded Moroccan and Mexican bank sectors, and proliferating private money-transfer agencies.

In 2008, Mexico received approximately US$26.3 billion and Morocco US$6.9 billion, according to the World Bank — an average of about US$2,300 per migrant from both Mexico and Morocco.

The global financial crisis has caused remittances to decrease modestly but not drastically (see Figure 2). This illustrates that remittances are a relatively stable income flow.

|

|

||

|

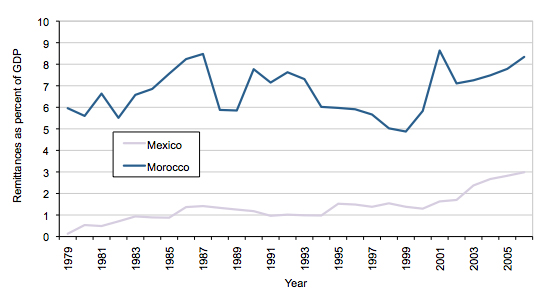

With remittances representing 8 percent of GDP in 2008, Morocco depends on remittances more than Mexico, where remittances accounted for 2.4 percent of GDP. The difference reflects the more underdeveloped state of the Moroccan economy although Mexico has become relatively more dependent on remittances over the past decades (see Figure 3).

|

|

||

|

The Mixed Impacts of Migration on Development

Whether migration affects development positively or negatively heavily depends on the perspective, scale, and timeframe adopted in the evaluation.

On the positive side, remittances have significantly improved the standard of living in migrant-sending regions in Mexico and Morocco alike. In many cases, remittances have allowed migrant families to buy land and invest. Although remittances spent on daily needs and construction are often dismissed as "nonproductive," they improve living standards. In particular, houses are considered secure investments in often insecure and unattractive investment environments.

Also, research has shown that while most remittances do not benefit the poorest, migrants' investments and expenditures back home do create some employment opportunities in areas such as the construction of private homes, agricultural projects (e.g., organic plums and peaches in Jerez, Mexico, and saffron production in Taliouine, Morocco), agriculture-related industry (e.g., the cultivation and processing of agave for the distilled spirit mezcal in Juchipila, Mexico), and infrastructure for tourism (e.g., guesthouses in southern Morocco).

But migration-induced change can also increase social and economic inequalities, particularly when the poor cannot migrate due to migration controls and/or the high cost of securing illegal passage.

The more dynamic migrant investors the study group visited in Morocco and Mexico appeared to belong to the relatively well-to-do and educated. The owner of a rose-water distillery in southern Morocco had trained in chemistry in Morocco and obtained a higher degree in France. Two of the three entrepreneurs who ran guesthouses catering to foreign tourists had received higher degrees in Morocco; one of them was the son of the local traditional chief.

While generally beneficial for individuals, families, and the communities involved, migration's impact on regional development and growth is much more contested. A central observation of the study tours was that depending on the general development context, migration impacts differ across and even within regions. Even more importantly, the study tours observed that migration tends to reinforce preexisting development trends and may therefore set in motion positive (virtuous) as well as negative (vicious) migration-and-development circles.

For example, in relatively isolated and disadvantaged areas, migration may further accelerate population decline and undermine economic productivity. However, in these cases, migration is a symptom, not a cause, of such decline.

The relative isolation of villages in mountainous areas of Zacatecas and some of the smaller, difficult-to-reach oases in southern Morocco marginalize them from economic interaction with more central parts of Mexico and Morocco, respectively. In turn, this lack of economic interaction hinders their development. Young adults then leave these traditional settlements in search of opportunities elsewhere. The resulting depopulation can create "ghost towns" where only a few households are left, among them a handful of young families with children.

By contrast, centrally located and economically thriving areas and regions are more likely to lure migrants and remittances back in; migrants from other parts of the country may relocate their remaining family members to these places, and migrants know that investments in such areas are more likely to produce returns than investments in rural hometowns. These decisions can further accelerate growth, particularly in urban centers. Within rural regions, migrants often prefer to invest in and return to "migrant boomtowns," accelerating existing urbanization trends.

In the case-study regions, two growing urban centers — Jerez in Zacatecas, Mexico, and Tinghir in the Todgha Valley, Morocco — have experienced these trends. Each city, home to a large emigrant population, received investments from migrants over the past decades. These investments stimulated development and economic growth, which in turn attracted internal migrants from surrounding areas.

Migrants' activities and types of investments can evolve as migrants age and/or conditions in origin countries change.

Until the 1990s, most migrant investments in Morocco were in land, housing, education, and individual enterprises, such as taxis and grocery stores. More recently, commercial investments appear to have increased; these include projects in tourism, agriculture, manufacturing, and trade. Generally improved investment conditions and the tourist boom in Morocco made it more attractive for migrants to invest.

In Mexico, migrants are involved in entrepreneurial ventures that allow them to use skills acquired in the United States. For instance, the study tours observed that migrants who worked in agriculture in California have introduced new techniques to farms in Zacatecas.

Migrants' position in destination countries greatly influences their inclination to invest. Migrant investors often had legal status and jobs, and they were well-integrated socially and economically before returning to Mexico and Morocco.

Also, general investment conditions at home greatly affect migrants' investment decisions. Morocco launched its national "2010 Vision" in 2001 to boost investment in tourism with the goal of attracting 10 million tourists to Morocco each year. By 2004, the number of tourists to Morocco exceeded 5 million for the first time, and the country's tourist infrastructure had noticeably improved.

While the Moroccan government envisions international groups such as Thomas Cook and Club Med investing in its tourism industry, small private investors, among them migrants, have seized opportunities. The Moroccan government's schemes to support farming improvements also seem to have attracted migrant investors.

Collective Remittances and Hometown Associations: Successes and Failures

Migrants with roots in the same village or region have long formed what are known as hometown associations (HTAs), organizations that allow migrants to collectively invest in projects at home, whether repairing a church or building a well.

Many HTAs, concerned with defending their position at home and in the destination country, organize themselves in networks to increase their influence in negotiations with politicians in both places.

HTAs of Moroccans and Mexicans have supported small-scale infrastructure, education, and health-care projects in local communities to improve general well-being. Such initiatives have a limited impact on local economic growth.

In other cases, HTAs get involved in agricultural projects by creating cooperatives or agricultural infrastructure or supporting business investments. Examples include a mezcal factory in Zacatecas supported by the Mexican government's three-for-one program (Tres por Uno), which matches every dollar from HTAs with three from the government, and a French-Moroccan migrant association called Migrations et Développement that supported the introduction of saffron farming in southern Morocco.

While the mezcal factory largely failed because it did not account for the powerful competition of established tequila producers, the second project was more successful. However, there is no evidence that even the more promising initiatives brought about a more general process of regional growth.

HTAs seem to operate differently in Mexico and Morocco. The national network of Mexican HTAs has shown comparative effectiveness in promoting migrants' interests, lobbying for their rights, and giving them a voice both in the United States and Mexico.

The fragmentary and multilingual composition of Moroccan HTAs, coupled with the lower levels of literacy and education among Moroccan migrants compared to Mexicans migrants, has given them weaker lobbying power in the receiving countries than Mexicans in the United States. However, Moroccan migrant organizations seem to have a stronger focus on development in regions of origin than their Mexican counterparts.

Although policymakers celebrate "collective remittances," the visits and discussions with migrants in Morocco and Mexico highlighted their mixed success and limited scope of collective initiatives.

First, not all projects the group visited and examined succeed — and several fail — because of a lack of feasibility studies and technical support from government agencies, poor implementation of activities, difficult project sustainability, unfavorable investment conditions, or difficulties marketing agricultural and industrial products. Migrant associations have limited capacity and power to overcome structural economic problems and to compensate for the failure or absence of national development policies.

Second, philanthropic projects do not appear to trigger development without changes in general development conditions. Much more important are private, family-to-family remittances, which can improve living standards and boost investment and economic growth in migrant-sending regions.

Third, migrant organizations in particular were worried that too strong an emphasis on collective remittances could shift responsibility for development away from governments and toward migrants and their associations. Indeed, the work of HTAs can also be seen as a symptom of and response to states' failure to provide basic infrastructure, accessible health care, and good education.

Fourth, most migrants are not willing or able to become entrepreneurs or "development workers." The expenditure and investment choices migrants make primarily reflect their legitimate interest in improving the livelihoods of their own families and, to a certain extent, communities. When governments or development agencies project exaggerated hopes and expectations onto migrants and their associations, the likely result is policy failure.

Fifth, migrant projects do not necessarily support initiatives that would most help local communities. In highly politicized local contexts, charitable activities and (prestige) projects such as new plazas, churches, or mosques may primarily fulfill the needs of local-migrant elites, which can lead to greater inequality rather than contributing to local development or poverty alleviation.

For example, the study tour visited a small clinic in a Mexican village, which actually did not need the facility as a larger, state-run clinic existed in a nearby town. Similarly, using government money to match migrants' collective funds to convert a village square into a cement and covered plaza and a parking lot might not be a priority for a small, declining rural community.

The same could be said of initiatives supported in Morocco. A guesthouse was renovated using international development funds, but it did not have a marketing strategy after three years of operation. Instead, the owner, who was the son of a former migrant, depended on the migrant organization to find the customers for his five guest rooms.

The Presence/Absence of the State

Both the Moroccan and Mexican states have devised strategies to encourage and co-fund migrant-driven development initiatives, although they have different approaches.

As mentioned earlier, Mexico has a three-for-one program through which national, regional, and local governments directly co-fund migrants' projects. However, these development activities are generally not part of a broader, government-directed development strategy.

In Morocco, the government funds broader development programs to boost agriculture and tourism in which migrants can insert themselves and apply for funding. As part of "co-development" policies, some European states and development agencies have contributed to development projects Moroccan HTAs started. Some HTAs have used their role in rural development projects to persuade the government that development is possible and is ultimately its responsibility.

The study tours and background studies revealed that governments' role in migrant initiatives is ambiguous, contested, and not necessarily desirable.

Many migrants actually prefer to avoid state involvement in order to preserve their autonomy. The idea that governments should engage migrants patronizes them because migrants have engaged in development for decades on their own terms.

Government involvement in HTA projects could also have a set of unintended consequences: dependency on government money and a subsequent loss of entrepreneurial spirit. The guesthouse in Morocco mentioned above is a clear example of an investment that needed and continued to lean on a migrant organization. Without the migrant organization's involvement, this guesthouse could not be profitable and would have an uncertain future.

In Juchipila, Mexico, the inability to use the mezcal factory to its full potential and to efficiently market the product led to great disappointment. Furthermore, the HTA's entrepreneurial spirit has fizzled.

Reframing the Debate

Evidence from the study tours suggests the following:

- Legitimate individual and family needs primarily drive migrants' interests in development. Only secondarily are migrants interested in promoting the development of entire communities and regions.

- Unfavorable economic and political conditions at the local, regional, and national levels make investments and development projects difficult to design and implement, and often lead to their failure.

Because development is a condition for attracting migrants' income-generating investments rather than a consequence of it, policymakers would be wise to reverse their perspective on migration and development. Rather than asking what migrants can do to support development, governments would be better off identifying how to make conditions attractive for migrant investments.

This means including migrants in general national development efforts rather than "insulating" them in specific migration-and-development policies, such as the three-for-one program in Mexico.

Morocco's approach might be a step in the right direction, as migrant associations can apply for general national human development funds. Emigrants' investments and development initiatives in Morocco and Mexico yielded more positive results when they took place in growth sectors and were part of a broader development strategy.

In general, though, independent evaluations of such projects are needed since governments nor HTAs are keen to openly discuss project failures.

A key observation and hypothesis to explore is that migration can perhaps make the largest difference in "semi-peripheral" regions, where economies are neither booming nor declining, but where they have potential for growth. In these places, remittances might trigger a virtuous cycle by pushing regional economies over a certain tipping point, leading to accelerated growth. A comparative study of regions and towns whose growth is related to migrants' circulation and investments would provide significant insights into the conditions under which migration can boost development processes.

Policies that include migrants in the development process should also not presume migrants will return or that those who do come back are responsible for bringing development. In addition, targeting only migrants as potential beneficiaries of government funding excludes (often poorer) nonmigrants who might have innovative ideas.

Destination countries have an important role here as well. During this economic crisis, European countries in particular have attempted to encourage the return of migrants. But when return policies require migrants not to come back, destination countries are actually pushing migrants into semi-permanent settlement. Policies linking return to development typically fail precisely because they seek to limit migrants' rights.

While migrants can potentially accelerate development at home, they can neither be blamed for a lack of development nor be expected to generate development in unattractive investment environments. Indeed, remittances and investments alone cannot remove or overcome more structural constraints. As the comparison of Mexico and Morocco has shown, sending and receiving states play a crucial role in ensuring that migration has positive development impacts.

Sources

Berriane, Mohamed and Mohamed Aderghal. 2008. The state of research into international migration from, to and through Morocco. Report prepared for the African Perspectives on Human Mobility programme. Mohammed V University – Agdal, Morocco. Available online.

———. 2010. Migration/développement: Etude de faisabilité pour l'adaptation du program mexicain 3 pour 1 au cas du Maroc. Available online.

Castles, Stephen and Raúl Delgado Wise. 2008a. Migration and Development: Perspectives from the South. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. Available online.

———. 2008. Perspectives from the South: Conclusions from the 2006 Bellagio Conference on Migration and Development. Available online.

de Haas, Hein. 2005. Morocco: From emigration country to Africa's migration passage to Europe. Migration Information Source, October 2005. Available online.

Version française: Maroc: De pays d'emigration vers passage migratoire africain vers l'Europe.

———. 2006a. Engaging Diasporas: How governments and development agencies can support diaspora involvement in the development of origin countries. Oxford: International Migration Institute and Oxfam Novib. Available online.

———. 2006b. Migration, Remittances and Regional Development in Morocco. Geoforum 37(4): 565-580. Available online.

———. 2006c. Trans-Saharan Migration to North Africa and the EU: Historical Roots and Current Trends. Migration Information Source, November 2006. Available online.

———. 2007. Impact of international Migration on social and economic development in Moroccan sending regions: a review of empirical literature. IMI Working Paper Series, WP 3-2007. Available online.

de Haas, Hein and Simona Vezzoli. 2010. Migration and development: Lessons from the Mexico-U.S. and Morocco- EU experiences. IMI Working Paper Series, WP 22-2010. Available online.

International Migration Institute. 2009. A transatlantic comparison of South-North migration: The experiences of Mexico and Morocco. Policy Brief No. 1. Available online.

———. 2009. Enriching the migration and development debate: Suggestions from an experience in the field. Policy Brief No. 2. Available online.

———. 2010. Migration and development: New perspectives on the Mexico-U.S. and Morocco-EU comparison. Policy Brief No. 3. Available online.

———. 2010. Report on the Study-tour in Ouarzazate, Morocco. Available online.

Lacroix, Thomas. 2005. Les réseaux marocains du développement : Géographie du transnational et politiques du territorial. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Vezzoli, Simona. 2009. Report on the Study-tour in Zacatecas, Mexico. Available online.

Vezzoli, Simona with Thomas Lacroix. 2010. Building bonds for migration and development: Diaspora engagement policies of Ghana, India and Serbia. Discussion Paper. Eschborn, Germany: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ) GmbH. Available online.

Websites

International Migration Institute, University of Oxford

Transatlantic Dialogues on Migration and Development Issues

Fondation Hassan II pour les Marocains Résidents à l'Etranger

Immigration Développement Démocratie

National Alliance of Latin American and Caribbean Communities

Migration and Development theme at the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ)