You are here

The Travel Ban at Two: Rocky Implementation Settles into Deeper Impacts

The Trump administration's travel ban provoked swift protests at U.S. airports. (Photo: Joe Piette/Flickr)

Editor's note: This article was updated in June 2019 to correct the share of refugee admissions for nationals of 11 countries determined to be high-risk, in the article as well as Figure 3.

Though the Trump administration’s travel ban was born in controversy and resulted in a flurry of public protests and legal challenges that reshaped one of the President’s first executive orders, two years on the much-contested policy has demonstrated a widespread impact on the admission of foreigners from the banned countries, while also reshaping U.S. security vetting procedures and the refugee resettlement process.

It was not an accident that the travel ban, issued precisely one week into the presidency of Donald Trump on January 27, 2017, was one of his first actions. Immigration has been central to the Trump campaign and presidency, as the recently ended, 35-day partial federal government shutdown over funding for a border wall underscored.

The stated rationale for the travel ban was that the U.S. government needed a more rigorous review of the information it received from foreign countries to properly vet foreigners seeking admission. While undertaking this 90-day review, the entry of immigrants and visitors from seven designated countries (all Muslim-majority: Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen) was suspended. The initial executive order sought to pause refugee resettlement to conduct a similar, 120-day review of the entire refugee admissions program, and indefinitely suspend the admission of Syrian refugees. The order, which did not outline any specific exceptions, and the ensuing chaos at airports spurred more than 40 federal court challenges. As a result of those lawsuits, eight federal courts granted injunctions or temporarily restrained parts of the travel ban, preventing individuals and groups of people—such as those with valid visas and arriving refugees—from being denied entry. Then on February 3, 2017, a U.S. district court in Washington blocked the enforcement of all provisions of the executive order relating to the travel ban.

With the original travel ban stalled in the courts, the administration issued a revised version on March 6, 2017. It still suspended entry of immigrants and visitors from six Muslim-majority countries—Iraq was removed—and paused refugee admissions for 120 days. However, it outlined specific exceptions for groups such as legal permanent residents, dual nationals of banned countries, and refugees already formally scheduled to travel. A federal court enjoined the executive order before it went into effect, but the Supreme Court in June 2017 allowed it to go forward for those foreign nationals lacking “bona fide” ties to the United States.

The third and final iteration of the travel ban, issued on September 24, 2017 via presidential proclamation, narrowed the classes of visitors blocked from eight designated countries: Chad, Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen, though Chad was removed from the list in April 2018. It also set up a waiver process, whereby otherwise blocked foreign nationals could enter the United States if they established that denying their entry would cause undue hardship, and their entry would not pose a national-security or public-safety threat and would be in the U.S. national interest. Lawsuits again challenged this version of the travel ban, reaching the Supreme Court for resolution. The justices were presented with three arguments against the travel ban: the President had not made a sufficient finding that banning the entry of these nationalities would be detrimental to the national interests, the proclamation unlawfully discriminated based on nationality, and it unconstitutionally discriminated based on religion. On June 26, 2018, the Supreme Court upheld the third version of the travel ban as both statutorily and constitutionally permissible.

Travel Ban Policies Currently in Effect

The administration has been able to implement many policies outlined in the travel ban not only because of the Supreme Court decision, but also because several provisions were never blocked by the courts. The result of these policies has been to reduce the number of visas issued by barring certain immigrants and visitors from entering the United States, lengthening the application process for those seeking admission, or providing more opportunities for consular officers to use their discretion to deny visas.

Visa Restrictions on Nationals of Designated Countries

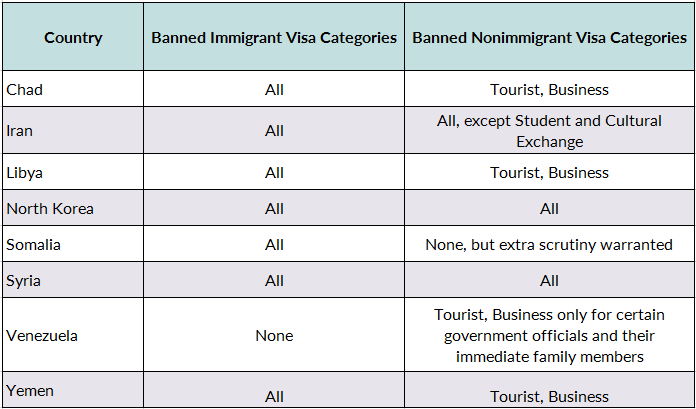

In December 2017, the Supreme Court allowed restrictions on immigrants and visitors from all eight original designated countries in the third iteration of the travel ban to go into effect. For most of the designated countries, all immigrants planning to move permanently to the United States are banned, while the policies vary for different groups of shorter-term visitors (see Table 1).

Table 1. Immigrants and Visitors Banned Under Presidential Proclamation of September 24, 2017

*Chad was removed from the travel ban on April 10, 2018.

Source: President of the United States, “Proclamation 9645 of September 24, 2017: Enhancing Vetting Capabilities and Processes for Detecting Attempted Entry into the United States by Terrorists or Other Public-Safety Threats,” Federal Register 82, no. 186 (September 27, 2017): 45161-45172, available online.

Suspension of the Visa Interview Waiver Program

The Visa Interview Waiver Program, established as a pilot in 2012 and made permanent in 2014, allowed certain low-risk, frequent travelers to renew or obtain nonimmigrant (temporary) visas online, without appearing for an in-person interview at a consular office. The program was suspended in July 2017 for applicants whose prior visas expired between one and two years before their new application and for certain first-time Argentine and Brazilian applicants. Those younger than 14 or older than 79, and those whose prior visa expired within a year of the new application were not affected.

Additional Biographic and Social Media Information Required from Certain Visa Applicants

Beginning in May 2017, consular officers started requesting that certain visa applicants who they determined needed more vetting provide all their social media handles for the past five years and their biographical information for the past 15 years, potentially prolonging and, in some cases, making it difficult for people to comply with the application requirements. While it is impossible to know if this practice is a direct result of the travel ban, the first two versions did call for the government to create a program to identify people trying to enter the United States fraudulently seeking to do harm; one of the methods suggested was to amend application forms to include “questions aimed at identifying fraudulent answers and malicious intent.”

The government in March 2018 proposed rules asking all immigrant and nonimmigrant visa applicants to provide their social media handles for the past five years; these have not yet been implemented.

Additional Information Required from Refugee Applicants

In October 2017, while the administration announced it would resume the refugee admissions program following the 120-day suspension, it also unveiled new security measures, including collecting additional biographic information, requiring applicants to renew their security checks if they add or change information in their applications, and subjecting more applicants to Security Advisory Opinions—a lengthier and deeper form of vetting. In addition, in January 2018, the administration decided to apply even more scrutiny to refugees from 11 high-risk countries, reportedly including additional interviews of applicants’ family members and “close scrutiny of potential ties to organized crime.” These countries were never officially named, but are reported to be Egypt, Iran, Libya, South Sudan, Yemen, Sudan, Iraq, Mali, North Korea, Somalia, and Syria.

Declining Immigrant, Visitor, and Refugee Admissions

The impact of the executive order and refugee-screening measures is evident in the declining numbers of annual visa issuances and refugee admissions of nationals from the designated countries.

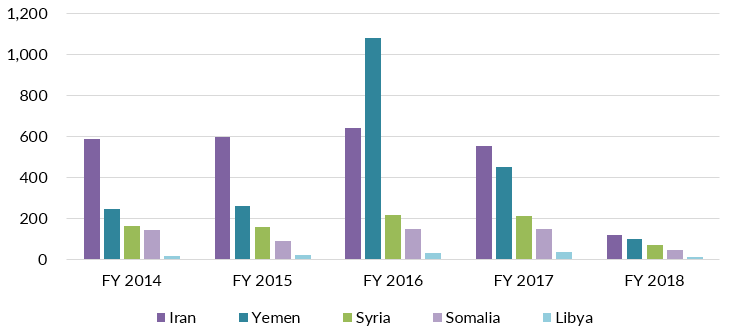

Visas issued to nationals of the five countries that were subject to the third ban’s broad limitations on travel decreased steeply between fiscal year (FY) 2017 and 2018. (North Korea and Venezuela are excluded from this calculation, as very few visas are issued annually to North Koreans, and the only Venezuelans subject to the travel ban are certain government officials and their families.) Monthly immigrant visa issuances to nationals of Iran, Libya, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen were down an average of 72 percent between FY 2017 and 2018 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Average Monthly Immigrant Visas Issued to Nationals of Travel Ban Countries, FY 2014-18

Source: U.S. Department of State, “Table XIV: Immigrant Visas Issued at Foreign Service Posts (by Foreign State Chargeability) (All Categories) Fiscal Years 2009-2018,” accessed January 22, 2019, available online.

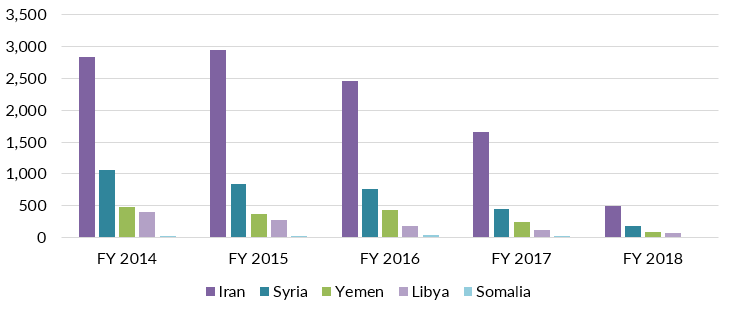

Monthly nonimmigrant visa issuances also declined between FY 2017 and 2018, by an average of 51 percent (see Figure 2). The decrease was greatest for Iranians, who in FY 2017 were granted an average of 1,650 nonimmigrant visas per month and in 2018 were granted 501.

Figure 2. Average Monthly Nonimmigrant Visas Issued to Nationals of Travel Ban Countries, FY 2014-18

Sources: U.S. Department of State, “Table XVIII: Nonimmigrant Visas Issued by Nationality (Including Border Crossing Cards) Fiscal Year 2008-2017,” accessed January 22, 2019, available online; U.S. Department of State, “Monthly Nonimmigrant Visa Issuance Statistics – Fiscal Year 2018 – NIV Issuances by Nationality and Visa Class,” accessed January 22, 2019, available online.

While the number of people affected by the travel ban is a very small component of the overall admission of temporary and permanent migrants to the United States, the impact on the designated countries has been significant. Not only have visa issuances sharply declined, but the process for obtaining a waiver for those who qualify has proven to be lengthy, with significant human cost. Indeed, news stories and research have highlighted a few of these cases: a Yemeni mother who was denied entry for months to see her dying toddler son; a Somali boy in a Kenyan refugee camp whose father died and who had waited more than three months to join his mother at the time of a July 2018 report; Iranian researchers who were blocked from attending a U.S. research conference; and almost 4,000 spouses and more than 5,000 adopted minor children who have been prevented from joining their U.S.-citizen partners and parents, according to a Cato Institute analysis. As of the end of August 2018, 1,607 travel ban waivers for cases such as these had been granted, though it seemed the rate of waiver issuance recently has shown signs of increasing. The total number of applications considered for waivers is unknown.

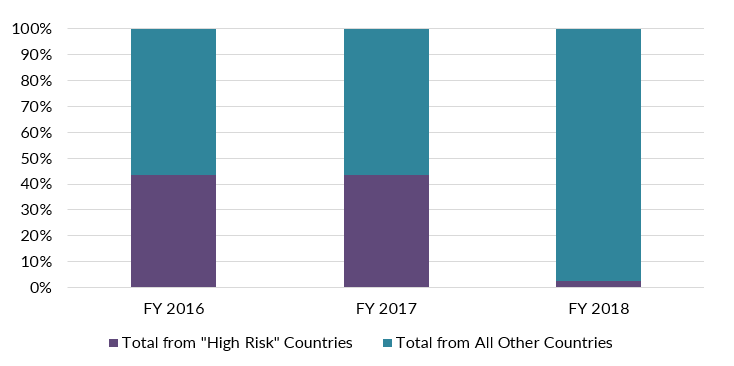

The pause in refugee admissions for nationals of 11 countries who were determined to be high-risk and the subsequent additional vetting has hugely shrunk the share of refugees admitted from those countries: they fell from 43 percent of all refugee admissions in FY 2017 to 3 percent in FY 2018 (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Refugees Admissions to the United States from High-Risk and Other Countries, FY 2016-18

Sources: U.S. Department of State Refugee Processing Center, “Admissions Reports -- Refugee Admissions Report December 31, 2018,” accessed January 22, 2019, available online.

The travel ban and related policies have thus significantly reshaped the entire refugee program.

Possible Future Developments

One of the reasons the Supreme Court upheld the third iteration of the travel ban was that it allowed for case-by-case waivers. An early-stage lawsuit in federal court in California, Emami v. Nielsen, contends, however, that the Trump administration has “a policy or practice of denying or stalling virtually all visa issuance and waiver grants” to people from countries on the travel ban list, arguing that a process should be put in place to more systematically adjudicate waiver applications. While it is too early to know whether this lawsuit will move forward, it is important to note that the plaintiffs are challenging the implementation, not the validity, of the travel ban: they are not asking that it be struck down, but rather that its provisions be fully implemented.

Though the principal measures of the first two iterations of the travel ban were blocked by courts to different degrees, other measures have remained in effect and likely resulted in significant policy changes. Despite some reporting that the administration was considering extending the travel ban to additional countries, it has chosen not to do so, demonstrating a degree of caution. Today, travel-ban opponents have confined their challenges to its implementation, not its lawfulness, while nationals of banned and restricted countries have seen their prospects of reaching the United States diminish.

- Executive Order 13769 of January 27, 2017: Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States

- Executive Order 13780 of March 6, 2017: Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States

- Proclamation 9645 of September 24, 2017: Enhancing Vetting Capabilities and Processes for Detecting Attempted Entry into the United States by Terrorists or Other Public-Safety Threats

- Lawfare resource on travel-ban executive order litigation

- Supreme Court opinion in United States v. Hawaii

- Reuters article on increased security vetting for certain visa applicants

- Proposed rules to collect social media information from all nonimmigrant and immigrant visa applicants

- U.S. government memorandum detailing increased security measures for refugee applicants

- Washington Post article on security measures for refugees from 11 high-risk countries

- Vox article on travel-ban waivers

- Class-action complaint in Emami v. Nielsen, challenging implementation of waiver process

- Cato Institute analysis of family separation resulting from the travel ban

National Policy Beat in Brief

Federal Court Rules Against Census Citizenship Status Question. A U.S. district judge in New York ruled on January 15 that the Commerce Department could not include a question about citizenship status on the 2020 Census. The decision to include this question, announced in March 2018, was arbitrary and capricious, according to the judge, because Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross “alternately ignored, cherry-picked, or badly misconstrued the evidence in the record before him; acted irrationally both in light of that evidence and his own stated decisional criteria; and failed to justify significant departures from past policies and practices.” Although he determined the addition of the question to be unlawful, the judge did not find it to be unconstitutional because of a discriminatory intent, as the plaintiffs had argued.

The Supreme Court was initially scheduled to hear arguments in February in a related case over what evidence could be permitted in the New York trial. But on January 18, it removed that case from its docket upon request of those challenging the inclusion of the question. Shortly thereafter, the administration announced it would attempt to bypass the Second U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and instead appeal the district judge’s decision directly to the Supreme Court. It requested to have the case heard in April or May, so that a final decision can be reached before the census questionnaires have to be printed in June. Meanwhile, separate trials on the citizenship question are moving forward in courts in California and Maryland.

- NPR article on the lower court ruling

- Associated Press article on the Supreme Court appeal

- October 2018 Policy Beat on the citizenship status question

Tornillo Camp for Unaccompanied Minors Shuts Down, Camp in Florida to Expand. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) shut down the Tornillo, Texas tent camp for unaccompanied migrant children in early January, releasing 2,800 of the minors it was holding and transferring 300 others to other shelters. The camp, established in June 2018, was designated as temporary, meaning that it was not governed by state child welfare regulations but rather by HHS guidelines. Its population swelled along with that of the overall unaccompanied minor population in HHS custody when the Trump administration in June 2018 started requiring fingerprints and background investigations, including immigration status checks, of both a child’s potential sponsor and everyone in that sponsor’s household, before releasing the child from HHS custody. The administration dropped the requirement for other household members in December. Even as Tornillo, with its capacity of 3,800, closes, the government is expanding another temporary shelter in Florida so it can hold 1,000 additional children, for a total of 2,350 at that shelter.

- Washington Post article on the closing of Tornillo

- New York Times article on the expansion of the Florida camp

- Federal Register notice from May announcing the screening requirements for sponsors and household members

Supreme Court Unlikely to Consider DACA Appeal This Term. On the last day that the Supreme Court typically decides which cases to hear in its current term, the justices did not choose to hear the administration’s appeal of three cases that have blocked the government from fully terminating protections for young unauthorized immigrants under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. The Justice Department appealed all three cases to the Supreme Court before federal appellate courts had the opportunity to rule on them. If the Supreme Court does take up the appeal, it likely would not hear arguments until the fall and would not issue a decision until 2020, meaning that current DACA recipients can continue to renew their work authorization and protection from deportation through then. With the Supreme Court unlikely to hear the case this term, Democrats in Congress may feel less pressure to find a legislative solution that protects DACA recipients, thus removing some of the Republicans’ leverage in funding fights over the border wall.

- Vox article on the Supreme Court’s lack of action on the DACA appeals

- MPI DACA data tools

Democratic-Led House Committees Begin Oversight of Immigration Agencies. The Democratic chairs of House committees are already indicating that they will conduct broad oversight of the executive-branch departments responsible for immigration functions. Rep. Bennie Thompson (D-MS), Chair of the Homeland Security Committee, sent a letter to Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen requesting that she testify at a hearing that will focus on “critical border-security matters, to include the border wall, metering of individuals seeking asylum at ports of entry, and the treatment of children in U.S. Customs and Border Protection” custody. The committee will also seek to draw a comparison between the administration’s handling of the northern and southern borders by investigating the security of the northern border. Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-NY), Chair of the Judiciary Committee, sent letters to HHS, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and the Justice Department requesting specific documents and answers to questions related to the zero-tolerance and family separation policies. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross will testify before the Oversight Committee in March, with questions likely focusing on the status of the census citizenship question. However, HHS Secretary Alex Azar has declined a request from the House Energy and Commerce Committee chair to testify on family separation.

- The Hill article on request that Secretary Nielsen testify

- Letters from House Judiciary Committee Chairman Jerrold Nadler to immigration agencies

- Politico article on Democrats’ northern border investigation

- House Oversight Committee press release on Secretary Ross’ upcoming testimony

- Politico article on Secretary Azar’s refusal to testify

Mexico and United States Implement New Policies toward Central American Migrants. Both Mexico and the United States have recently implemented new ways of dealing with Central American migrants who arrive at their southern borders. When a caravan of Central Americans—mainly Hondurans—reached the Guatemala-Mexico border in mid-January, the Mexican government began to issue humanitarian visas for those who requested them, attracting other Central American migrants who were never part of an organized caravan. Mexico has received more than 12,000 visa applications, mostly from Hondurans. Mexican authorities fast-tracked humanitarian visas for the migrants for about two weeks, with the wait time down to days, from what would typically be months. However, the government ended the expedited program on January 29, saying migrants seeking humanitarian visas in the future will have to apply from their home countries.

At the same time, DHS announced that it would begin implementing its Migrant Protection Protocols—better known as the Remain in Mexico policy, announced in December 2018—sending non-Mexican asylum applicants who arrive at the U.S. Southwestern border back to Mexico until a decision is issued in their asylum case. Those who can show they are more likely than not to be persecuted in Mexico are excepted. The program will start as a pilot at the San Ysidro Port of Entry, near San Diego, with the plan to eventually expand it to the rest of the Southwest border.

- Los Angeles Times article on Mexico’s humanitarian visas

- Wall Street Journal article on Mexico ending fast-tracked humanitarian visas

- CNN article on Remain in Mexico

- DHS guidance memorandum on Remain in Mexico

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services guidance memorandum on Remain in Mexico

December Apprehensions of Families at Southern Border Set New Record. There were more than 27,000 children and adults traveling as families apprehended at the U.S.-Mexico border in December, a record high since tracking of such migrants began in 2012. Every month since September 2018 has broken the historical record for families apprehended. Almost 76,000 family members have been taken into U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) custody at the border in the first three months of fiscal year (FY) 2019—compared to 76,000 in all of FY 2017 and 78,000 in FY 2016. Meanwhile, the total number of apprehensions at the Southwest border has held steady at about 50,000 total apprehensions of all migrants from October to December, still higher than recent years.

- USA Today article on border apprehensions

- Department of Homeland Security press release on December statistics

Flood of Temporary Work Applications Leads to Re-evaluation of Order in Which to Process Them. On January 1, 2019, the first day that employers could submit applications to the Labor Department for temporary or seasonal nonagricultural workers on H-2B visas, the department’s portal crashed due to high demand: it received applications for 97,800 workers, for 33,000 visas available. This is a sharp increase from past years. For example, on January 1, 2018, the department received applications for 81,600 workers, and in the first week of January 2017, for 53,200 workers. The demand on this date likely surged because in order to adjudicate applications on a first-come, first-serve basis, the department is now ordering processing based on the millisecond in which each application came in. Earlier processing in the Labor Department means the employers can send their petitions to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) sooner, for visa issuance. The Labor Department may now consider other processing methods, including a lottery.

- Wall Street Journal article on increased H-2B demand

- Labor Department Office of Foreign Labor Certification news updates on application processing

State and Local Policy Beat in Brief

New York City to Provide Comprehensive Health Care for All Residents, Including Unauthorized Immigrants. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced January 8 that his administration will guarantee health care through the city’s public hospitals to every city resident, regardless of ability to pay or immigration status. About half of the 600,000 uninsured residents that the program would serve are unauthorized immigrants. Through the program, these residents could visit any of 70 clinics that are part of the city’s hospital system and see a primary care physician, with costs determined on a sliding scale. They will also be able to see specialists. The city will provide the hospitals $100 million annually to support care for this population.

- New York Times article on the program

- New York City Mayor’s Office press release detailing the program

Tennessee County Refuses to Implement New State Law Requiring Detainer Compliance. Shelby County, Tennessee, will not hold potentially removable noncitizens based on detainers issued by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), despite a new state law that prohibits restrictions on detainer compliance. The county’s attorney found that complying with detainers was a likely violation of the Constitution, though the county will continue notifying ICE of upcoming releases of people that ICE suspects are removable. The Governor announced that his legal team will investigate the legality of Shelby County’s decision. A locality can be determined to be in violation of the new state law only if a citizen sues and a judge rules in his or her favor.

- Commercial Appeal article on Shelby County’s policies

- Associated Press article on the Governor’s response

- Tennessee Public Chapter No. 973

Localities in Maryland and Massachusetts Limit Cooperation with ICE. Anne Arundel County, Maryland, withdrew in December from its 287(g) agreement with ICE, that it implemented only a year and a half prior, and which had allowed officers in its jail to determine inmates’ immigration status and removability. Because of this action, ICE soon after announced it would terminate its contract with Anne Arundel to house immigration detainees.

In Massachusetts, the City Council in Springfield overrode the mayor’s veto and passed an ordinance that prohibits city officials from asking individuals about their immigration status and prohibits compliance with ICE detainers and requests for notification in the absence of a judicial warrant.

- Capital Gazette article on the back-and-forth between Anne Arundel and ICE

- New England Public Radio article on the passage of Springfield’s “Welcoming Community Trust” ordinance

- Welcoming Community Trust ordinance

Governor of New York Pardons 22 Immigrants. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo pardoned 22 immigrants on December 31 whose criminal convictions, many for drug-related crimes, put them at risk of deportation. Cuomo has pardoned immigrants in similar situations four other times, though this was the most he has ever pardoned at once. While pardons may help legal permanent residents avoid deportation, unauthorized immigrants can still be removed based on their lack of legal status. And further, the Board of Immigration Appeals has held that pardons may not prevent deportation for drug offenses.

- New York Governor’s Office press release on the pardons

- Immigrant Defense Project FAQ on the reach of gubernatorial pardons