You are here

Trump's Promise of Millions of Deportations Is Yet to Be Fulfilled

Federal immigration officers make an arrest during an operation in Virginia. (Photo: U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement)

Editor's Note: This article was updated on February 3, 2021 to include data on interior removals for FY 2020.

Donald Trump entered office propelled by bold promises to make the U.S. immigration system more restrictive and more aggressively enforce its laws in the interior of the country. Ahead of the 2016 elections, the Republican presidential candidate pledged a “deportation force” that would remove millions of unauthorized immigrants. “We have at least 11 million people in this country that came in illegally. They will go out,” he claimed during one primary debate.

Yet after nearly four years in office, the president’s record on immigration—while remarkably faithful to his campaign agenda—did not keep up in at least one regard. Immigration enforcement in the U.S. interior during the Trump administration has lagged far behind the president’s 2016 electoral promises as well as the record of his predecessor, Barack Obama. In fact, the Trump administration deported only slightly more than one-third as many unauthorized immigrants from the interior during its first four fiscal years than did the Obama administration during the same timeframe. Immigration arrests and removals have taken on a higher profile under Trump because of highly visible worksite enforcement operations and increased arrests in residential neighborhoods and sensitive locations such as courthouses, among other tactics.

But the large number of deportations promised has remained elusive, mostly due to resistance from state and local officials who have advanced “sanctuary” policies that limit cooperation with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). The Trump administration’s failures on this front stand in stark contrast to the White House’s achievements in narrowing legal immigration, virtually ending asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border, building new barriers, reducing refugee resettlement, and hundreds of other executive actions to reshape the immigration system.

During the final weeks of the campaign, the administration has renewed its focus on immigration enforcement, seeming to offer the president a reliable peg to close out his re-election message. Just two weeks before Election Day, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced it would fast-track deportations of unauthorized immigrants if they have been in the United States less than two years, expanding its use of expedited removal beyond the border zone. The move came on the heels of a DHS announcement that ICE would increase enforcement in jurisdictions that refuse to cooperate with its mission. And ICE also, notably, in the closing weeks of the campaign erected a series of billboards in the presidential battleground state of Pennsylvania, showcasing immigrants facing criminal charges who were not turned over to the agency by local authorities.

Through speeches, news conferences, press releases, and sharp tweets, senior DHS and ICE leaders have amplified Trump’s image as a protector of public safety, drawing concern from former officials who say the leadership is politicizing ICE and DHS to the detriment of both.

The recent actions thus provide an insight into the role interior enforcement plays in electoral politics. If granted a second term, Trump is likely to make arrests and removals of deportable noncitizens even more of a priority. On the other hand, if Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden wins, he will be under immense pressure to reverse the Trump policies and revert, at a minimum, to those in place at the end of the Obama administration, which protected the vast majority of unauthorized immigrants from arrest and removal.

State and Local Resistance Slowed Trump’s Deportation Plans

Despite issuing a highly publicized executive order that significantly expanded the enforcement authority and leeway of ICE officers just five days after he took office, Trump has seen arrests and deportations idle, especially when compared to the peak Obama years. This is due to significant resistance from state and local jurisdictions that have limited their cooperation with ICE. Given that most ICE arrests and removals originate with local jails and state prisons, the “sanctuary” policies adopted by California, New York City, and other jurisdictions with high numbers of unauthorized immigrants have served as a significant brake on ICE enforcement.

However, the administration has found some ways to circumvent these jurisdictions, including by taking enforcement action through U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). The recent move to fast-track deportations through expedited removal, which allows an ICE officer to make a decision to remove a noncitizen without having to take the case through the immigration courts, represents another such effort.

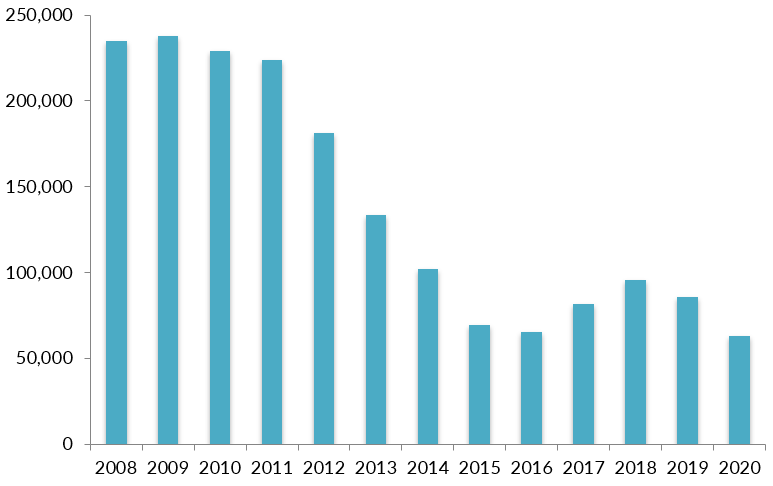

Figure 1. Removal of Noncitizens from Within the U.S. Interior, FY 2008-20

Note: Interior removals are the result of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) operations in the interior of the country.

Source: ICE, “Enforcement and Removal Operations Report,” multiple years, available online.

The Federal-Local Tussle on Interior Enforcement

In 1996, Congress established the federal government’s authority to seek the cooperation of local law enforcement agencies to be force multipliers for enforcing immigration laws as part of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act, which also vastly expanded the reach and speed of the removal process. The infusion of resources in the wake of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks gave extra muscle to such cooperative arrangements. Together with increased information-sharing between law enforcement and federal immigration authorities, this cooperation drove removals from the interior to the high watermark under the Obama administration. From 2008 to 2011, the year ICE arrests peaked at 322,093, more than 85 percent of noncitizens arrested by the agency were transferred from state and local law enforcement agencies.

As the number of deportations increased, this cooperation became hugely controversial and increasingly politically polarized, and Obama was famously labeled the “deporter in chief” by critics in the immigrant-rights community. In response to this backlash, in 2014 the Obama administration introduced a slew of reforms that focused attention on more serious criminals and tailored cooperation to the needs of local law enforcement. Under strong pressure from immigrant-rights advocates who complained of racial profiling by some local law enforcement agencies, the administration curtailed the 287(g) program, which authorized certain state or local law enforcement officers to assist with the investigation, apprehension, or detention of unauthorized immigrants.

The Obama administration also shut down Secure Communities, a federal-state information-sharing program that examines the fingerprints of individuals booked into state or local custody and flags for enforcement noncitizens identified as removable. Secure Communities was initiated during the Bush administration and was rolled out to all of the country’s 3,181 state and local jurisdictions under Obama, during which it became highly controversial as the pipeline for a record number of deportations. In 2014 the Obama administration replaced Secure Communities with the Priority Enforcement Program (PEP), which allowed jurisdictions to negotiate the terms of their cooperation and limited ICE detainers or notification requests to removable noncitizens who met the administration’s narrowed enforcement priorities.

However, the efforts to ease the federal-local tensions were quickly undone as the Trump administration took office and announced muscular enforcement policies. In response, state and local governments’ embrace of “sanctuary” policies increased. For many jurisdictions, cooperation with ICE came to signal support for the administration’s immigration agenda.

While the Trump administration has pursued other avenues for increasing arrests and removals in the U.S. interior, including by quadrupling worksite enforcement efforts, local jurisdictions’ resistance has been key in its failure to deport the millions of unauthorized immigrants the president promised.

Trump Efforts to Engage and Pressure Local Law Enforcement

In response, the administration has employed strong-arm tactics, including threats to withhold federal funding from “sanctuary” jurisdictions and carry out ICE operations in their back yard, and, more recently, issuing subpoenas and lawsuits against reluctant state and local law enforcement agencies. But local resistance has risen perhaps higher than ever.

One of the most contentious issues in this federal-local tussle is whether state and local law enforcement agencies are required to honor ICE requests known as detainers, which ask that they hold suspected removable immigrants for an extra 48 hours past the release date so that ICE has time to arrest them. While ICE detainer issuance rose by 20 percent from FY 2014 to FY 2019, the number of detainers that were declined by jurisdictions increased by 89 percent.

To circumvent local jurisdictions’ resistance, the administration has placed a high priority on revitalizing and expanding the two programs undone by the Obama administration: 287(g) and Secure Communities. In May 2019, ICE created a new form of 287(g) agreements, the Warrant Service Officer (WSO) program. After a day of training, participating officers are deputized to issue administrative immigration arrest warrants, which ICE argues allows them to hold detainees for two days to execute a transfer of custody to ICE. In some jurisdictions this serves as a countermeasure to detainer noncompliance policies. As of September, ICE had executed WSO agreements with 73 law enforcement agencies in 11 states. It had also signed 287(g) agreements with 77 law enforcement agencies in 21 states, well more than doubling the 30 agreements in effect when Trump took office.

In early 2017, the Trump administration restored Secure Communities, scuttling the PEP program. From January 25, 2017 through April 2019, more than 150,000 noncitizens were removed as result of Secure Communities.

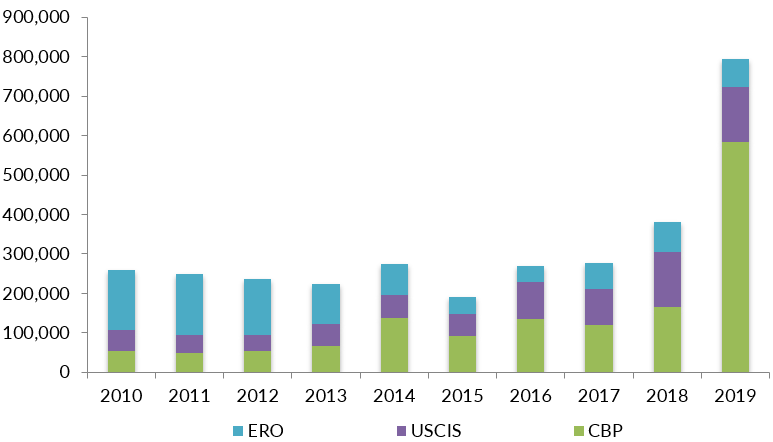

Increased Reliance on USCIS

Over its tenure, the Trump administration has increasingly deployed the immigration benefits agency USCIS for enforcement purposes. The agency’s spending on detecting immigration benefit fraud has doubled, and spending on vetting of applications has tripled. This has resulted in the agency more frequently initiating removal proceedings against applicants for the various benefits it adjudicates, by issuing Notices to Appear (NTAs) in immigration court. From 2010 to 2016, USCIS issued an average of 58,000 NTAs annually, while in 2019 the agency issued 140,396 NTAs.

Figure 2. Issuance of Notices to Appear by Agency, FY 2010-19

Notes: ERO = Office of Enforcement and Removal Operations at U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement; USCIS = U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services; CBP = U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The significant rise in notices to appear (NTAs) issued in 2019 by CBP is as a result of the increased arrivals at the southern border, which more than doubled between 2018 and 2019.

Source: U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Immigration Statistics, “Immigration Enforcement Actions,” multiple years, available online.

Expedited Removal

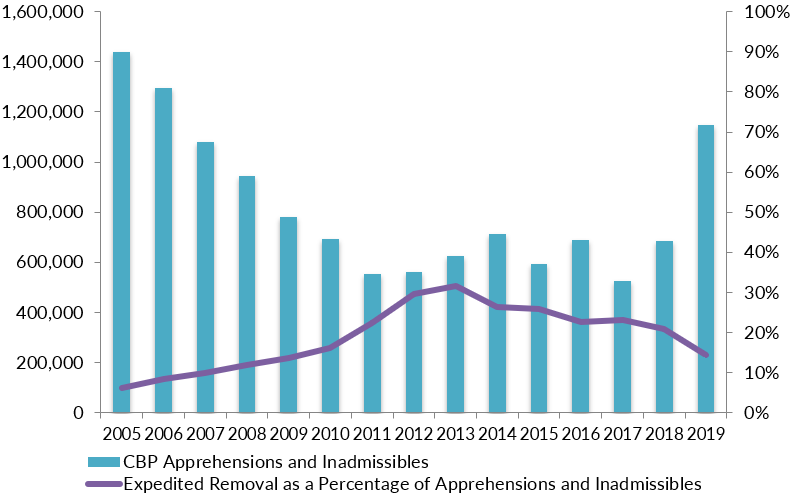

The 1996 laws that set the terms of federal-local cooperation on interior enforcement also created the process of expedited removal. Under the law, unauthorized immigrants who have been physically present in the United States for less than two years after having entered or attempted to enter illegally, including through the use of fraud or false documents, may be removed without a hearing before an immigration judge.

Despite this broad authority, expedited removal was applied more narrowly by earlier administrations. In 2004, President George W. Bush confined use of expedited removal to within 100 miles of the land or sea border, which covers regions in which two-thirds of the U.S. population lives. He also limited it to individuals who had entered illegally in the prior 14 days. Even then, his administration used expedited removal only on a subset of these apprehensions, usually individuals with criminal records.

In 2011, the Obama administration began implementing a targeted system of consequences for migrants who crossed or attempted to cross the southern border illegally. The initiative, named the Consequence Delivery System, significantly increased the use of expedited removal relative to overall apprehensions, but did not increase the scope of individuals subject to expedited removal.

On October 21, 2020, ICE announced it was implementing a policy to expand this program nationwide, making the Trump administration the first to fully apply expedited removal throughout the entire U.S. territory.

Figure 3. Expedited Removals as a Share of CBP Apprehensions and Inadmissibles, FY 2005-19

Notes: “Inadmissibles” are individuals who attempted to enter the country through a port of entry but were declared inadmissible. Currently, most individuals placed in expedited removal come into custody after having been apprehended or declared inadmissible by CBP.

Sources: DHS, Office of Immigration Statistics, “Immigration Enforcement Actions,” multiple years; U.S. Border Patrol, “Nationwide Illegal Alien Apprehensions Fiscal Years 1925-2019,” available online.

The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) estimates the expansion of expedited removal to the U.S. interior could apply to as many as 288,000 people, given this is the number of unauthorized immigrants who have resided in the United States for less than two years after entering illegally. Even though this is a relatively small portion of the total unauthorized population of 11 million, robust use of expedited removal in the U.S. interior could lead to a rise in the climate of fear for millions. It also could result in the deportation of individuals for whom it was not intended, given the fast-track nature of the process and the agency’s history of mistakenly detaining and deporting some U.S. citizens and permanent residents.

When individuals are apprehended by federal immigration authorities, they bear the burden of proving they are lawfully present or have been continuously present in the United States for more than two years. If they are unable to convince an immigration officer, they could potentially be summarily removed without the chance to see an immigration judge. According to internal ICE guidance released as part of a lawsuit regarding the expansion of expedited removal, foreign nationals will be given a “brief but reasonable opportunity,” at most 72 hours, to present evidence of their physical presence, such as through leases, school, or employment records.

Changes Ahead?

Interior enforcement is at a crossroads, and its future is likely to hinge on the outcome of the presidential election. While border enforcement may have dominated the public’s attention on immigration during much of the Trump administration, more robust interior enforcement is the president’s unaccomplished mission. It would likely be a priority if Trump were to win re-election.

A Biden administration would face vexing choices to unwind the measures that the Trump administration put in place while also being more than simply a replay of the Obama administration, which still evokes ire from many in the Democratic Party’s base for its record number of arrests and deportations.

A review of the Biden campaign website, public statements, and the policy recommendations released by a “Unity Task Force” of individuals appointed jointly by Biden and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) shows Biden’s position on interior enforcement has evolved over time, partly in response to a leftward push from the Democratic base.

After serving under Obama, Biden has struggled to distinguish himself on immigration while remaining true to his pragmatic bent. “We made a mistake,” Biden said during the final presidential debate about the Obama administration’s record on deportations and failure to enact sweeping immigration reform. Voters should trust that he can reform the system now, he added, because “I’ll be president of the United States, not vice president of the United States.”

While not going as far as advocating for abolishing ICE, as some on the left have pushed, Biden has expressed openness to re-evaluate some Obama-era policies, including those regarding enforcement. For example, Biden has committed to a 100-day moratorium on removals, possibly to allow for a review of current practices and development of recommendations to reforming ICE and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) enforcement policies and practices.

If Biden were to simply restore the ICE enforcement priorities in place at the end of the Obama administration, the focus would be on removable noncitizens deemed a threat to public safety or national security. When those policies were put in place, MPI estimated that 87 percent of unauthorized immigrants were not priorities for enforcement. However, it is likely that Biden will face pressure from advocates to focus even more narrowly and confine enforcement to individuals with serious criminal records.

A Biden presidency would also likely empower local jurisdictions to set their own levels of cooperation and priorities for immigration enforcement. According to the unity document, Biden would reverse the use of 287(g) agreements and similar programs that engage local law enforcement in immigration enforcement. This would repeat the Obama administration’s latter-years de-emphasis of the role of local law enforcement. Its more flexible approach to cooperation under PEP, which replaced Secure Communities, actually increased cooperation with ICE by state and local law enforcement agencies. Two years after the creation of PEP, at the end of FY 2016, DHS announced that 21 of the 25 largest jurisdictions that had previously declined the largest numbers of detainers were cooperating with ICE.

The unity document also promises to end workplace and community enforcement operations, but does not specify what, if anything, would take their place. Workplace enforcement still occurred under the Obama administration, though the administration moved away from high-visibility enforcement operations in favor of “desktop audits” that focused more on employer compliance in documenting worker status and less on onsite investigations and arrests. And ICE operations in the community also occurred during the Obama administration. In fact, during FY 2009-11, ICE averaged 40,000 at-large arrests per year, similar to the first two years of the Trump administration. Both of these policies would likely get a fresh review in a Biden presidency.

The next four years are likely to bring about a change in approach to immigration enforcement in the interior of the country. The Trump administration’s unfulfilled ambitions and late-term actions on expedited removal suggest a second term would see a bold push on interior enforcement. Biden’s priorities are slightly more ambiguous, and he would likely be torn between a return to Obama-era policies and adopting a new posture more in line with the progressive wing of his party.

Sources:

American Civil Liberties Union. N.d. Know Your Rights: 100 Mile Border Zone. Accessed October 24, 2020. Available online.

American President Project. N.d. National Political Party Platforms. Accessed September 25, 2020. Available online.

Biden, Joe and Donald Trump. 2020. Remarks during October 22, 2020 presidential debate. Rev transcript, October 22, 2020. Available online.

Biden for President. N.d. Biden-Sanders Unity Task Force Recommendations. Accessed October 24, 2020. Available online.

---. N.d. The Biden Plan for Securing Our Values as a Nation of Immigrants. Accessed September 25, 2020. Available online.

Capps, Randy, Muzaffar Chishti, Julia Gelatt, Jessica Bolter, and Ariel G. Ruiz Soto. 2018. Revving Up the Deportation Machinery: Enforcement under Trump and the Pushback. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Capps, Randy, Faye Hipsman, and Doris Meissner. 2017. Advances in U.S.-Mexico Border Enforcement: A Review of the Consequence Delivery System. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Jessica Bolter. 2020. The U.S. Presidential Campaign Cements Political Parties’ Deepening Schism on Immigration. Migration Information Source, October 1, 2020. Available online.

Gomez, Melissa. 2020. Biden Commits to Moratorium on Deportations of Immigrants. Los Angeles Times, March 15, 2020. Available online.

Make the Road New York et al. v. Kevin McAleenan et al. 2019. Administrative Record. Civil Action No. 1:19-cv-02369-KBJ, U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. Available online.

Meissner, Doris, Donald M. Kerwin, Muzaffar Chishti, and Claire Bergeron. 2013. Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Pierce, Sarah and Doris Meissner. 2020. USCIS Budget Implosion Owes to Far More Than the Pandemic. Migration Policy Institute commentary, June 2020. Available online.

Rosenblum, Marc R. 2015. Understanding the Potential Impact of Executive Action on Immigration Enforcement. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). N.d. Removals under the Secure Communities Program: ICE Data through April 2019. Accessed October 24, 2020. Available online.

Trump, Donald. 2016. Remarks during CNN/Telemundo GOP Candidates Debate in Houston, Texas. CNN, February 25, 2016. Available online.

---. 2019. Twitter post. June 17, 2019, 9:20 pm. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2016. DHS Releases End of Year Fiscal Year 2016 Statistics. Press release, December 30, 2016. Available online.

---. 2019. Designating Aliens for Expedited Removal. Federal Register 84 (141), July 23, 2019. Available online.

---. N.d. Delegation of Immigration Authority Section 287(g) Immigration and Nationality Act. Accessed October 24, 2020. Available online.

U.S. DHS, Office of the Inspector General (OIG). 2020. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s Criminal Alien Program Faces Challenges. Washington, DC: DHS, OIG. Available online.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). 2015. ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report Fiscal Year 2015. Washington, DC: ICE. Available online.

---. 2017. Fiscal Year 2016 ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report. Washington, DC: ICE. Available online.

---. 2020. DHS, ICE Announce Arrests of More Than 170 At-Large Aliens in Sanctuary Jurisdictions. Press release, October 16, 2020. Available online.

---. 2020. Fiscal Year 2019 Enforcement and Removal Operations Report. Washington, DC: ICE. Available online.

---. 2020. Fiscal Year 2020 Enforcement and Removal Operations Report. Washington, DC: ICE. Available online.

---. 2020. ICE Launches Billboards in Pennsylvania Featuring At-Large Public Safety Threats. Press release, October 2, 2020. Available online.