Tuareg Migration: A Critical Component of Crisis in the Sahel

The Tuareg (or Touareg)—a nomadic pastoralist group of Berber origin—have been enmeshed in a complicated struggle against the Malian state since January 2012, with their initial revolt paving the way for attacks by Islamist rebels. The resulting coup d'etat and occupation of northern Mali by the Tuareg and Islamist insurgents fighting for independence from the Malian government marked the latest in a series of long-simmering Tuareg conflicts with West African nations, with earlier eruptions of violence occurring in the early 1960s, the early and mid-1990s, and several years ago.

Generally, Tuareg grievances have revolved around autonomy, nationality, and movement, with some variation in Tuareg justification from one rebellion to the next. In many ways, migration is an integral component of these conflicts, which are further fueled by poverty and accentuated by drought.

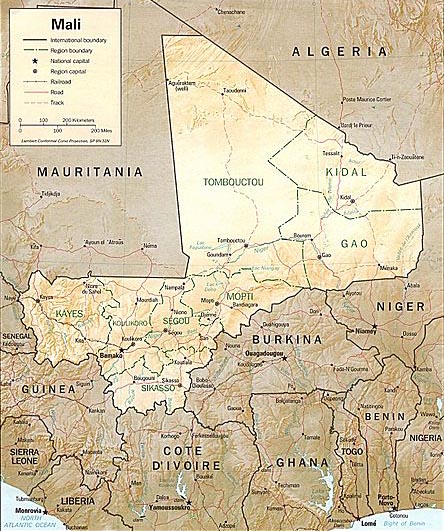

The Tuareg have no country of their own but instead migrate throughout the western Sahel, crisscrossing the countries of Algeria, Burkina Faso, Libya, Niger, and Mali. Popular culture has romanticized the indigo-blue veiled Tuareg as outlaws, "Blue People," hommes de nulle part (men from nowhere), and chevaliers du désert (knights of the desert). The Tuareg are adherents of Islam, but retain some idiosyncratic practices, such as the traditional requirement that men—but not women—wear veils.

For the Tuareg, continuous migration—the constant, unrestricted movement for trade and agricultural purposes—has always been a primary means of survival and an integral part of their culture. During and after French colonization, restricted freedom of movement contributed to severe economic difficulty and the formation of deep-seated antagonism toward certain state leaders.

The exact cause of the 2012 conflagration in Mali is disputed. Some scholars argue that limited access to arable land during and after the colonial period is the main cause of Tuareg discontent; others argue that the return of Tuareg to Mali from Libya—where they were lured for recruitment into Muammar Qaddafi's militias and heavily armed upon the dictator’s downfall—constitute the primary factor; and still others blame the governments of Mali and Niger, whose creation upon the decolonization of West Africa signaled, from a Tuareg standpoint, a new form of colonization over the Tuareg by other African groups.

It is unlikely that these three reasons, even together, offer a complete account of the causes of Tuareg discontent and a push for separatism. Nevertheless, when taken together, they help delineate the principal causes of the conflict, and undoubtedly further illuminate the contours of this debate, which has increasingly gained international involvement. With the gradual withdrawal of French troops from Mali beginning in April 2013, various European and international bodies are stepping in to find a way to bring the crisis—which has caused widespread deaths, displacement, and food insecurity—to a close.

This article explores the unique role that migration plays in shaping Tuareg grievances in the context of the revolt in Mali.

|

Figure 1. Map of Mali and Neighboring Countries

|

||

|

French Colonialism

Although for much of the pre-colonial period there were many kingdoms (such as the Songhai Empire) throughout North and West Africa, the Tuareg moved freely throughout the region because most polities were without defined or enforced borders. The Tuareg managed trade routes for gold, ivory, salt, and black African slaves, and provided services to trade caravans throughout the Sahel.

This changed when the French colonized nearly all of North and West Africa in the late 1800s—a region of immense ethnic, cultural, and linguistic diversity. The French found Tuareg dominance incompatible with their goal of expanding the French empire, and therefore sought to weaken the Tuareg stronghold. Eventually, the French gained control despite Tuareg resistance.

The French also employed divisive strategies to establish greater control over the region, at times encouraging a sense of ethnic superiority in the Tuareg people. On the other hand, the French extended positions of authority only to "les évolués" (the "evolved" or "developed") from within other African ethnic groups, without regard for the Tuareg population—an act of manipulation which had lasting consequences. When Mali achieved independence from France in 1960, the Tuareg immediately became a disadvantaged and under-represented minority ruled over by other groups, whom the Tuareg considered (and arguably still consider) their inferiors.

Much of Africa was thrown into tumult by European colonial powers: artificially imposed borders profoundly affected the future of the continent, dividing up tribes, lumping discordant tribes together, and generating countries whose geographies almost destined them to perpetual hardship.

Mali and its neighbor Niger were no exceptions. The fixed borders of these fledgling nations further exacerbated tensions between the Tuareg and other African groups, laying the foundation for longstanding—and still unresolved—disputes. Importantly, the Tuareg were now unable to traverse the Sahel as freely as they were once accustomed to and were split up and isolated from each other, divided among several nations.

Tuareg Migration: The Climate Factor

The Sahel is known for its dangerously capricious climate, variable rain patterns, and droughts—a situation worsened by climate change and the southern expansion of the Sahara. Traditionally, the Tuareg adapted by creating customs of usage and passage rights so that families and clans could migrate to more lush areas when necessary. When the land became too arid to cultivate, the Tuareg, who are typically livestock farmers, migrated to better pastures. Land was subject to a customary system of collective ownership, an arrangement accepted by both nomadic pastoralists and sedentary farmers for centuries.

European colonization disrupted this long-established system. French, British, and Italian troops controlled different portions of Tuareg territory and imposed their own administrations and colonial frontiers. The French attempted a policy of land registration and succeeded in a limited fashion.

Subsequent establishment of post-colonial states further marginalized the Tuareg and deprived them of access to land. Some Tuareg leaders considered this loss of access to land and power not only a threat to physical survival, but also to their culture; continuous migration is a basic tenet of Tuareg identity. With limited land available and sedentarization, overuse and subsequent degradation of the land was inevitable.

Additionally, soil exhaustion and resource scarcity have accelerated due to severe droughts that cyclically plague the Sahel. In the 1970s and '80s, severe droughts fueled internal conflicts and diminished resources for the Tuareg. Again, although the Tuareg were once experts in withstanding the harsh and unpredictable desert environment, internal migration to wherever they pleased was no longer an option. Thousands of Tuareg and their livestock died.

To make matters worse, the Tuareg felt that this humanitarian crisis was largely ignored by the Malian government, and that government officials in Bamako, the capital, embezzled scant relief funds. (Note, also, that the Tuareg were not alone in their frustration with government corruption; the Malian population at large was fed up, as evidenced by widespread student strikes). While Tuareg resentment towards the Malian and Niger governments heightened, they began to migrate en masse to Libya (and Algeria) due to the extreme drought. There, they were exposed to revolutionary discourses, stoking separatist passions.

Migration to Libya: Formation of a Resistance Movement

The Tuareg who migrated to Libya in the 1970s and '80s were mostly single men between the ages of 15 and 35 who carried with them the accumulating grievances of their people toward the governments of Niger and Mali. These young men were searching for jobs to support their families back home. Libya proved particularly attractive because Qaddafi offered large sums of cash to the Tuareg for joining his military.

Scores of Tuareg joined the military and served as mercenaries in Qaddafi's Islamic Legion—an armed force whose function was to build a unified Islamic state in North Africa. Qaddafi deftly used Tuareg labor, dispatching them to fight in numerous regional conflicts as well as in Lebanon and Sri Lanka. By the 1980s, the Tuareg possessed significant military prowess.

This experience likely fostered a stronger sense of unity and shared purpose among the Tuareg. While in Libya, the Tuareg told their stories of plight and identified with one another, developing (perhaps for the first time) a feeling that they all belonged to one overarching Tuareg "nation" across the Sahel. From these conversations, a more significant discourse ensued by the late 1980s, as certain Tuareg revolutionary groups emerged determined to restore Tuareg culture and unify the dispersed Tuareg people through armed rebellion.

Also by the late 1980s, the worldwide collapse of oil prices and the subsequent instability of the Libyan economy led to the dissolution of Qaddafi's Islamic Legion. As a result, hundreds of Tuareg found themselves once again unemployed, but now with significant military expertise. Many of them returned to Mali, newly emboldened.

Conflict initiated by the Tuareg arose in Mali in the early 1990s. (The Tuareg leaders of this rebellion would eventually also initiate the most recent uprising against the Malian state.) The 1990s conflict was settled with the Accords of Tamanrasset, whereby the Malian government granted numerous concessions to the Tuareg, such as the incorporation of some Tuareg insurgents into the Malian army.

When the Qaddafi regime fell in 2011, scores of Tuareg still in Libya, who had served in Qaddafi's military and fought for him during the Libyan civil war, returned to Mali and Niger. Interestingly, the Malian government allowed the Tuareg back into the country, even though the Tuareg brought with them sophisticated weaponry and transportation. The government of Niger, on the other hand, insisted that the Tuareg abandon their arms before entering Niger. The Tuareg thus posed a much more significant threat to the Malian army and state — a threat that manifested itself in January 2012.

Recent Mali Crisis: Forced Displacement and New Developments

The recent revolt against the Malian state was officially initiated by the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (known by its French acronym MNLA). MNLA is a Tuareg political separatist group, arguably secular, that is fighting for the establishment of Azawad (an area encompassing the northern Malian cities of Timbuktu, Gao, and Kidal) as an independent state. Its leadership includes many Tuareg who were once part of Qaddafi's army and migrated back to Mali.

The initial offensive took place on January 24, 2012 in Aguelhoc, where Malian soldiers suffered mass atrocities at the hands of the MNLA. Soon thereafter, more groups—including some Islamist groups—joined the rebellion, albeit with varying goals ranging from imposition of Islamic law in Mali to substantial dialogue with the Malian government. Some of the Tuareg generals in the Malian army in the north, who had been incorporated into the Malian army by the Accords of Tamanrasset, betrayed the Malian state and enabled Islamist groups like Ansar Dine and Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb to enter Timbuktu and Gao. Eventually, Islamist militant groups (whose membership actually includes Tuareg fighters) gained control and overpowered the MNLA.

People throughout Mali have lived in a state of chaos and fear since the beginning of the 2012 crisis. Wartime atrocities, underlying questions about the viability of the Malian state, and the imposition of a harsh interpretation of Islamic law led many civilians to flee.

By early 2013, there were around 300,000 refugees as a result of the Malian crisis, according to recent estimates by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre. This figure includes between 200,000 and 230,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs), 40,000 Malian refugees in Burkina Faso, and 50,000 in Niger. Many refugees have also resettled in Mauritania (perhaps more than 70,000 at the Mbera camp alone, according to an April 2013 report by Médecins Sans Frontières), Algeria, and other countries. Those who resettled are living in dismal conditions. The International Committee of the Red Cross has reported that displaced persons in the northeast corner of Mali lack food and water.

Only with French intervention in January 2013 did the conflict begin to subside, with French forces responding to Islamist militants' imminent advance on Bamako, and forcing the Islamist militants from northern cities and towns.

Persistent insecurity prevents the return of those who were displaced. For instance, even though French and Malian troops recaptured Gao last January, an al Qaeda-linked rebel group attacked the city, which is the largest city in Mali's north, soon thereafter.

Although some fighters remain in desert hideouts in the northern region, France withdrew its first batch of soldiers last April. With Malian elections expected in July, France plans to reduce its forces to 1,000 by the year's end. Both Western and African authorities remain concerned that Malian forces and soldiers of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS, a regional group whose primary goal is to promote economic integration) are inadequately prepared to take full control of the campaign against the Islamist militants.

Severe economic instability persists as well. The chairman of a local association of IDPs told UNHCR that "the situation in the north is critical," and "what awaits us there is worse than the situation here. Food is scarce, we have lost our animals and our houses have not been maintained all these months. We will need help when we go back."

Next Steps and Considerations

With the gradual withdrawal of most French troops on the horizon, African leaders and the international community are exploring other solutions to bring the crisis—which has caused widespread deaths and displacement—to a close. The Malian government plans to improve health and food security (among other necessities), and the European Union is determined to assist in the government's efforts: the European Commission and the 27 EU Member States have promised to provide 1.35 billion euros for Mali next year. Part of these donations will be put towards UN humanitarian and peacekeeping operations. ECOWAS has also pledged support for these upcoming operations.

Even as Tuareg migration to Libya planted the seeds for the violent revolt against the Malian state, migration may also be part of the solution—as a tool for development in the region. As the Tuareg have always known and often fought for, migration can counter negative economic shocks for those whose livelihood depends on unpredictable climates and land fertility. Greater freedom to move to "greener pastures," therefore, can be the means to alleviate poverty—the primary goal of development.

Sources

Abdalla, Muna. 2009. Understanding of the natural resource conflict dynamics: The case of Tuareg in North Africa and the Sahel. Institute for Security Studies. Available online.

Al Jazeera. 2013. France begins withdrawing troops from Mali. April 9. Available online.

Allison, Simon. 2013. Mali: five key facts about the conflict. Guardian Africa Network. January 22. Available online.

Amnesty International. 2013. Mali: Civilians at risk from all sides of the conflict. February 1. Available online.

BBC. 2013. Mali conflict: Chad army 'enters Kidal.' BBC News. February 5. Available online.

--. 2013. Mali Crisis: Key players. BBC News. March 12. Available online.

Benjaminsen, Tor. 2008. Does Supply-Induced Scarcity Drive Violent Conflicts in the African Sahel? The Case of the Tuareg Rebellion in Northern Mali. Journal of Peace Research 45: 819-836.

Charlton, Angela. 2013. AP Interview: Mali probes claims of atrocities. February 19. Available online.

Diarra, Oumar. 2012. Insecurity and Instability in the Sahel Region: the Case of Mali. U.S. Army War College. Available online.

Dorrie, Peter. 2012. The Origins and Consequences of Tuareg Nationalism. World Politics Review. May 9. Available online.

Dr. Alioune Sow. 2013. University of Florida, Assistant Professor in the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures and the Center for African Studies. Personal conversation.

Dr. Renata Serra. 2013. Lecturer at the Center for African Studies at the University of Florida. Personal conversation.

Edmond, Bernus. 1992. Etre touareg au Mali. Politique Africaine 47: 23-30. Available online.

Fessy, Thomas. 2012. Gaddafi's influence in Mali's coup. BCC News. March 22. Available online.

Fischer, Anja and Ines Kohl, eds. 2010. Tuareg society within a globalized world: Saharan life in transition. London: Tauris Academic Studies/I.B. Tauris. Library of Modern Middle East Studies.

George, Princy Marin. 2012. The Libyan Crisis and the Western Sahel: Emerging Security Issues. Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses. Available online.

Internal Displacement Monitoring Center (IDMC). 2013. Mali: A cautious return: Malian IDPs prepare to go home. Available online.

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). 2013. Mali: Drinking water a priority in north. February 18. Available online.

Keita, Kalifa and Dan Henk. 1998. Conflict and Conflict Resolution in the Sahel: The Tuareg Insurgency in Mali. Strategic Studies Institute. Available online.

Kisangani, Emizet. 2012. The Tuaregs' Rebellions in Mali and Niger and the U.S. Global War on Terror. International Journal on World Peace 29 (1): 59-97.

Krings, Thomas. 1995. Marginalisation and revolt among the Tuareg in Mali and Niger. GeoJournal 36 (1): 57-63.

Lange, Marie France. 1999. Insoumission civile et défaillance étatique : les contradictions du processus démocratique malien, in Autrepart. pp. 117-134. Available online.

Lecocq, Baz. 2010. Disputed desert: Decolonisation, Competing Nationalisms and Tuareg Rebellions in Northern Mali. Brill. Available online.

Médecins sans Frontières. 2013. Mauritania: Refugees Stranded in Desert. April 13. Available online.

Morgan, Andy. 2012. The Causes of the Uprising in Northern Mali. ThinkAfricaPress, February 6. Available online.

Moseley, William G. 2012. Azawad: The latest African border dilemma. Al Jazeera. April 18. Available online.

Nossiter, Adam. 2012. Qaddafi's Weapons, Taken by Old Allies, Reinvigorate an Insurgent Army in Mali. New York Times, February 5. Available online.

--. 2012. Soldiers Overthrow Mali Government in Setback for Democracy in Africa." New York Times, March 22. Available online.

Raoul-Dandurand, Chaire. 2002. Le conflit touareg au Mali et au Niger. Extraits du rapport du Groupe de Recherche sur les Interventions de Paix dans les Conflits Intra-étatiques- GRIPCI. Available online.

Schmitt, Eric. 2013. Terror Haven in Mali Feared After French Leave. The New York Times. March 17. Available online.

Simanowitz, Stefan. 2009. Bluemen and Yellowcake: The struggle of the Tuareg in West Africa. Media Monitors Networks. Available online.

Spence, Timothy and Frederic Simon. 2013. The Guardian. May 16. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2013. For Mali's displaced, on-going insecurity an obstacle to return. February 12. Available online.

UNHCR. 2013. UNCHR country Operations Profile: Mali Situation (Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso). Available online.