You are here

Two Decades after 9/11, National Security Focus Still Dominates U.S. Immigration System

A U.S. Customs official looks at wreckage in New York following the 9/11 attacks. (Photo: James Tourtellotte/U.S. Customs and Border Protection)

Twenty years since the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks and with the last U.S. troops now out of Afghanistan, the policies and programs enacted in response to 9/11 continue to leave sharp and lasting impacts on the U.S. immigration system, on the lives of immigrants, and on U.S. society writ large. All 19 hijackers were foreign nationals who were in the United States on nonimmigrant visas, and so immigration controls were inevitably seen as obvious tools in the “war on terror.” Two decades later, national security remains the dominant, if not exclusive, lens through which all immigration policy is viewed. The result is a highly securitized immigration apparatus with vastly increased budgets and large-scale arrests, detention, and removal of noncitizens based on significantly enhanced data-sharing between federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies.

While the immigration enforcement apparatus has flourished, the much-needed and long-overdue overhaul of the U.S. immigrant selection system to match the country’s modern-day realities and to address the status of a long-resident unauthorized immigrant population has floundered. The terrorist attacks derailed high-level discussions on major U.S. immigration reform that the United States and Mexico had been engaged in. On September 6, 2001, the two countries agreed on a framework for reform and declared that “U.S.-Mexican relations have entered their most promising moment in history.” The attacks five days later stopped this movement in its tracks, and attempts to restart the process in Congress have repeatedly failed.

With a single-minded focus on national security, the update of a legal immigration system last touched in 1990 and other immigration priorities, however urgent, have stalled in Congress. The 20-year-long congressional paralysis on most immigration issues thus remains a lasting legacy of 9/11.

Expanding Enforcement by Increasing Resources

To be sure, the groundwork for expanding immigration enforcement had been laid before the terrorist attacks. The 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA), passed in the aftermath of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, expanded the list of criminal convictions that made noncitizens deportable and subject to mandatory detention. It also set in place the framework for linking local law enforcement with federal immigration enforcement. However, many of the measures set out in IIRIRA laid dormant until 9/11 catalyzed the government to use all available authorities to expand immigration enforcement.

Defense against terrorism provided a reason to dramatically increase resources for immigration agencies identified as protecting homeland security, namely U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which has been charged with managing border security, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which is responsible for enforcing immigration laws in the interior of the country. A third new agency, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), handles adjudication of immigration benefits; it has received less of a resource boost. These agencies were the byproduct of the biggest restructuring of the federal bureaucracy since World War II—the creation of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in 2003—which aimed to unify government efforts involved in protecting the country.

Booming Funds for Immigration Enforcement

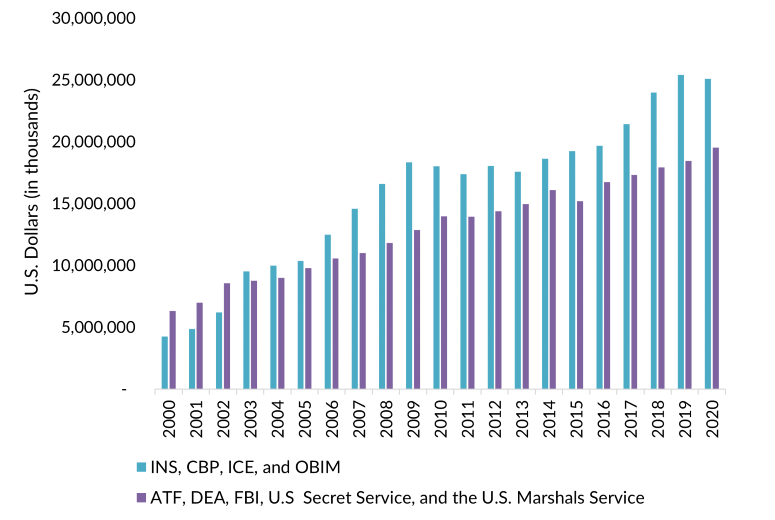

In fiscal year (FY) 2000, the budget of the agency that preceded CBP, ICE, and USCIS—the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS)— was $4.3 billion. Only a portion of this went to enforcement because the agency was also responsible for the adjudication of immigration benefits. By comparison, the INS budget was one-third smaller than the $6.3 billion allocated that fiscal year for the principal federal criminal law enforcement agencies (the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives [ATF]; the Drug Enforcement Administration [DEA]; the Federal Bureau of Investigation [FBI]; the Secret Service; and the U.S. Marshals Service).

Federal spending on immigration enforcement shifted dramatically after 9/11, significantly overtaking what the federal government spends on the principal federal criminal law enforcement agencies. By FY 2006, the budget of the immigration enforcement agencies within DHS was $12.5 billion—nearly triple the FY 2000 level and 18 percent more than the $10.6 billion appropriated that year for the federal government’s principal criminal law enforcement agencies. And by FY 2020, appropriations for immigration enforcement reached $25.1 billion, a nearly sixfold increase since FY 2000 and 28 percent more than the $19.5 billion directed to the principal federal criminal law enforcement agencies.

Collectively, since the creation of DHS, the United States has spent more than $315 billion on federal immigration enforcement.

Figure 1. Annual Budgets for U.S. Immigration Enforcement and Principal Federal Criminal Law Enforcement Agencies, FY 2000-20

Notes: Immigration enforcement data for 2000 cover the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS); in subsequent years, immigration enforcement was carried out by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the Office of Biometric Identity Management (OBIM). The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF); the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA); the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI); the Secret Service; and the U.S. Marshals Service are the federal government’s principal federal criminal law enforcement agencies.

Sources: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) analysis of archived Department of Justice Budget Summaries and Fact Sheets from 2000 through 2014, available online; Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Budgets-in-Brief from 2003 through 2020, available online; Department of Justice Budget Summaries and Fact Sheets from 2015 through 2022, available online.

As appropriations for immigration enforcement agencies have increased, so have their staffs. In FY 2000, INS had 32,000 employees; by FY 2020, staffing of the immigration components of DHS had tripled to 105,000 employees, accounting for 44 percent of the department’s 240,000 total employees.

Resources Drive Policy

Growing resources for ICE and CBP drove changes in policy. For example, Congress for many years provided ICE with increased funding for immigration detention, sometimes over and above what the agency requested. The 2004 Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act, which principally aimed to restructure and bolster the U.S. intelligence community, also required DHS to increase the number of available detention beds by 8,000 each year from FY 2006 through FY 2010, as appropriations allowed. From FY 2010 through FY 2012, congressional appropriations required ICE to maintain capacity to detain a minimum of 33,400 noncitizens, and from FY 2013 through FY 2017, a minimum of 34,000. This has meant that ICE has sought to detain at least that many noncitizens on average each day. These two measures contributed to a ballooning population in ICE custody, reaching an average of 50,000 each day in FY 2019, even though minimum bed requirements have been omitted from appropriations bills since FY 2018. In comparison, in FY 2000, the population in immigration detention on an average day was 19,000. The average daily population in immigration detention declined to 34,000 in FY 2020 due to ICE’s decreased operations during the COVID-19 pandemic and falling apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border.

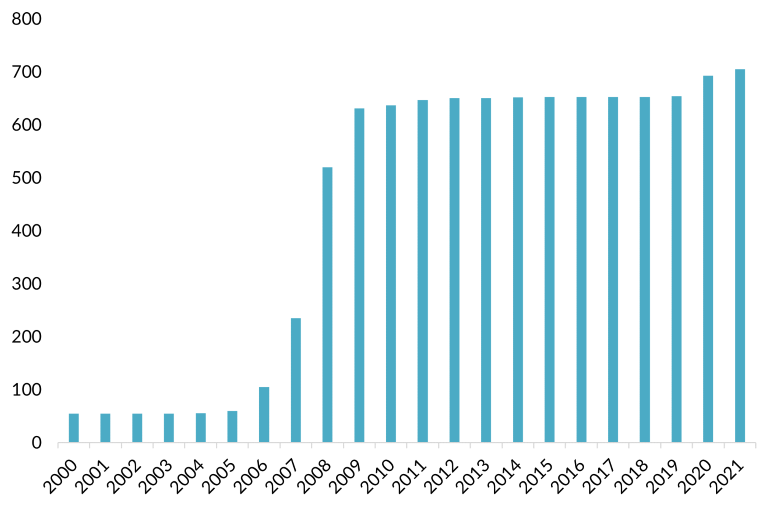

Similarly, construction of physical barriers started to play a bigger role in border security policy in the wake of 9/11. While the first major barriers along the U.S.-Mexico border were built in the 1990s, they tended to be built in discrete locations, typically in or near urban centers. But funds for border fencing and other construction increased dramatically in the early 2000s, tripling from $92 million in FY 2005 to $270 million in FY 2006. Further, the 2006 enactment of the Secure Fence Act directed a massive increase in border security measures and instructed DHS to attain operational control of the nearly 2,000-mile border, defined as preventing “all unlawful entries into the United States”—specifying that this would include blocking terrorists—through a network of barriers and technology. To achieve this unattainable goal, it required the construction of an unprecedented 700 miles of border barriers. Of the 702 miles of primary border fencing along the U.S.-Mexico border today, 570 miles were constructed between FY 2006 and FY 2009.

Figure 2. Miles of Primary Fence along the U.S.-Mexico Border by Year FY 2004-21

Notes: Primary fencing includes both pedestrian and vehicle fencing. The total miles of primary fencing built as of the end of FY 2019 is based on a CBP status report from mid-January 2020, so could be a slight overestimate. The total miles of primary fencing built as of the end of FY 2020 is based on a CBP status report from December 18, 2020, so could be a slight underestimate.

Sources: For FY 2000-18, William L. Painter and Audrey Singer, DHS Border Barrier Funding (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2020), available online; for FY 2019, John Burnett, “$11 Billion and Counting: Trump's Border Wall Would Be the World's Most Costly,” NPR, January 19, 2020, available online; for FY 2020-21, Robert Farley, “Trump’s Border Wall: Where Does It Stand?” FactCheck.org, December 22, 2020, available online.

A New Information Era

Consequent to the policies put in place post-9/11, a new era of information gathering and sharing was born, amid the belief that the attacks could have been foiled if information had been shared more widely across U.S. agencies operating nationally and internationally. One of the government’s goals, therefore, was to increase the reach and the interoperability of various government databases, including those connected to the immigration system.

Gathering Information on Arriving Foreign Nationals and Immigrants Already in the United States

A plethora of new programs emerged for gathering and sharing information. One of the first, and perhaps the most controversial, was the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS). From 2002 to 2003, NSEERS required noncitizen males ages 16 and older from 25 countries, 24 of which were Muslim-majority, to submit biometrics upon their arrival in the United States, with subsequent check-ins with immigration officials once inside the country. Those already in the country were required to present themselves at immigration offices for registration and questioning. In 2003, parts of the program requiring check-ins or questioning were suspended, but other elements, including the requirements to submit biometrics at ports of entry, were left in place until 2011.

By the time NSEERS was terminated it had become redundant due to the expansion of another data-gathering initiative. The U.S. Visitor and Immigrant Status Indicator Technology (US-VISIT) program was launched in 2004 as a large-scale effort to gather biometric data on all foreign nationals entering the United States. It followed the USA PATRIOT Act’s mandate to implement an automated entry-exit system, which Congress had previously ordered in 1996 but was never implemented. US-VISIT cross-checked personal information and fingerprint data of noncitizen travelers to the United States against other government terrorist, criminal, and immigration databases. In 2013, the functions of US-VISIT were incorporated into the newly formed Office of Biometric Identity Management (OBIM) within DHS. The database that this office operates, known as IDENT, held 220 million unique biometric identities as of 2017, making it the largest law enforcement biometric database in the world and the second largest biometrics database, after India’s national identity program, Aadhaar.

The USA PATRIOT Act also mandated the implementation of another program first called for by IIRIRA, to collect information from noncitizen students and exchange visitors in the United States. The fact that one of the 9/11 hijackers was on a student visa made tracking of students in the United States a priority. In 2002, INS launched the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS) to meet this mandate and check information submitted by applicants for student visas against criminal and terrorist databases. It also maintains information submitted by schools and colleges on international students’ courses of study and their enrollment status once they enter the country. ICE, which now runs SEVIS, is alerted if students violate the terms of their visas.

Finally, the Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11 Commission Act of 2007 required DHS to increase security of the Visa Waiver Program (VWP), which allows nationals of certain countries to enter the United States without a visa. The Electronic System for Travel Authorization (ESTA), established in 2008, allows CBP to screen biographical information of potential travelers against CBP and INTERPOL databases to determine their security risk and travel eligibility. In 2014, CBP expanded the information that it collects through ESTA in response to increasing concerns about foreign fighters from VWP-participant countries who had traveled to Iraq and Syria.

DHS and the State Department have also increased information sharing at consular missions worldwide through the Visa Security Program, which was created in 2003. Pursuant to this program, ICE special agents are deployed to diplomatic missions to screen, vet, and investigate applicants for nonimmigrant visas, and provide training to State Department consular officers on security threats. The Visa Security Program was first deployed in 2003 in Saudi Arabia and by 2021 had expanded to 41 posts in 28 countries.

The significance of increased sharing and interoperability of databases across government agencies cannot be understated. Pre-9/11, many of these agencies had considered their databases and institutional knowledge precious, proprietary, and not to be shared with other agencies.

Information on Immigrants inside the United States

The new era of information sharing has perhaps had its most dramatic impact in the increasing interoperability of federal, state, and local databases. It is a phenomenon that has led to a massive expansion of immigration arrests in the interior of the United States through programs such as Secure Communities and 287(g) agreements. In its section on immigration law and enforcement, the 9/11 Commission report identified “a growing role for state and local law enforcement agencies,” which “need more training and work with federal agencies so that they can cooperate more effectively with those federal authorities in identifying terrorist suspects.” However, both 287(g) and Secure Communities have grown beyond this original goal and have become enforcement dragnets that help sweep up all removable noncitizens, including unauthorized immigrants, who come in contact with state and local criminal justice systems.

The Secure Communities program, created in 2008, connects local law enforcement databases with FBI and DHS databases to determine whether arrested individuals have committed any past federal criminal or immigration violations. The information is sent to DHS, which determines the individual’s removability and can seek to transfer that person to ICE custody. By January 2013, Secure Communities was in effect in all 3,181 law enforcement jurisdictions in the country. That fiscal year, individuals flagged to ICE through Secure Communities accounted for 59 percent of all removals of noncitizens arrested inside the country; the following year, it accounted for more than 67 percent of interior removals. The Obama administration paused the program from 2014 through 2016, but the Trump administration restarted it in 2017 and it remains active today.

The 287(g) agreements allow state and local law enforcement officers to be deputized as immigration officers, which allows them to check arrestees’ information against DHS databases and issue immigration charges and detainers. Though 287(g) was established by Congress in 1996, the first agreement was not signed until 2002, with the state of Florida. While that and other initial contracts were narrowly tailored to target security threats, the focus of some local programs had broadened by the mid-2000s to include potentially all unauthorized immigrants.

Both the number of agreements and the number of noncitizens swept up through them increased in following years. In FY 2006, 5,700 noncitizens were identified as removable through 287(g) agreements; by FY 2009, that number was 56,000. In 2011 there were 72 such agreements in effect, although this number declined to 35 during the Obama administration before rebounding and reaching 148 agreements by the end of President Donald Trump’s term. Eight months into the Biden administration, there are 144. President Joe Biden’s campaign promises to limit the use of 287(g) agreements and terminate those signed with the Trump administration remain unfulfilled.

Government Secrecy Given the Green Light

Immediately after 9/11, U.S. counterterrorism authorities used immigration powers to arrest more than 1,000 foreign nationals, most of them Muslims from Arab and South Asian countries, whom the government viewed as potential national security threats. Instead of targeting them based on individualized suspicion and specific evidence, U.S. authorities often used national origin as a proxy for the risk they posed and defended the secrecy of their actions on national security grounds.

Secrecy became a hallmark of post-9/11 actions. The U.S. government withheld the names and locations of these detainees. About half had their immigration court proceedings closed to the public. In many of these cases, the government introduced secret evidence that was not made available to the defendants or their attorneys. Many were detained without warrants, arrested without a charge, and held even after judges ordered their release on bond or made final determinations in their cases.

Several of these practices—including keeping the names of detainees secret, prolonging immigration detention past necessary length, closing immigration hearings to the public, and holding detainees in harsh conditions solely based on their race, religion, or nationality—were challenged in court, but were generally upheld. Thus, even though these practices are not being used currently, they remain in the government’s arsenal of tools.

The Fallout

Beyond its direct impact on individuals, the near single-minded focus on immigration as a national security issue has come at a price in terms of immigration and national security policy. First, despite several attempts, Congress has failed to pass any comprehensive reform of the U.S. immigration system such as along the lines of the 2001 “grand bargain” outlined by Mexico and the United States. These comprehensive immigration reform proposals have included new employment-based visas, a process to legalize unauthorized immigrants in the United States, and increased immigration enforcement. Bills in 2006, 2007, and 2013 all failed to pass both chambers of Congress, stalling much needed reforms to an immigration system that has long been widely viewed as seriously broken.

Second, the oversized focus on immigration enforcement as a major component of the United States’ defense against terrorism has resulted in the diversion of resources away from other national security missions. This has arguably made the government slower to prepare for and respond to other critical threats, such as cyberattacks and domestic terrorism. Meanwhile, the formidable immigration enforcement machinery ostensibly built to safeguard national security has instead swept up hundreds of thousands of unauthorized immigrants with no criminal or terrorist history.

While national security and immigration enforcement must play a role in the overall U.S. immigration framework, the challenge is to balance those missions with other key functions of the system, such as responding to labor market demand and adjudicating immigration benefits. Twenty years after the tragic events of 9/11, the United States reassessed and ended the war in Afghanistan. It may be time to also reassess the appropriate place and scale of immigration enforcement in the nation’s priorities.

Sources

Alvarez, Priscilla. 2021. Defense Department Slams Brakes on Border Wall as It Reviews Biden Order. CNN, January 21, 2021. Available online.

Burnett, John. 2020. $11 Billion and Counting: Trump's Border Wall Would Be the World's Most Costly. NPR, January 19, 2020. Available online.

Burt, Chris. 2018. Inside the HART of the DHS Office of Biometric Identity Management. BiometricUpdate.com, September 4, 2018. Available online.

Capps, Randy, Marc R. Rosenblum, Muzaffar Chishti, and Cristina Rodríguez. 2011. Delegation and Divergence: 287(g) State and Local Immigration Enforcement. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Claire Bergeron. 2011. DHS Announces End to Controversial Post-9/11 Immigrant Registration and Tracking Program. Migration Information Source, May 17, 2011. Available online.

---. 2011. Post-9/11 Policies Dramatically Alter the U.S. Immigration Landscape. Migration Information Source, September 8, 2011. Available online.

Consolidated Appropriations Act. 2008. Public Law 110-161, U.S. Statutes at Large 121 (2007): 1844- 2456. Available online.

Farley, Robert. 2020. Trump’s Border Wall: Where Does It Stand? FactCheck.org, December 22, 2020. Available online.

Kolker, Abigail F. 2021. The 287(g) Program: State and Local Immigration Enforcement. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

Luan, Livia. 2018. Profiting from Enforcement: The Role of Private Prisons in U.S. Immigration Detention. Migration Information Source, May 2, 2018. Available online.

Meissner, Doris, Donald M. Kerwin, Muzaffar Chishti, and Claire Bergeron. 2013. Immigration Enforcement in the United States: The Rise of a Formidable Machinery. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States. 2004. The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Available online.

Painter, William L. and Audrey Singer. 2020. DHS Border Barrier Funding. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

Pope, Amy. 2020. Immigration and U.S. National Security: The State of Play Since 9/11. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Rosenblum, Marc R. 2011. U.S. Immigration Policy since 9/11: Understanding the Stalemate over Comprehensive Immigration Reform. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Secure Fence Act of 2006. 2006. Public Law 109-367, U.S. Statutes at Large 120 (2006): 2638-40. Available online.

Siskin, Alison. 2004. Immigration-Related Detention: Current Legislative Issues. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). 2003. Department of Homeland Security – The First Months. Special report, TRAC, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, August 2003. Available online.

U.S. Border Patrol. N.d. Border Patrol Nationwide Staffing by Fiscal Year. Accessed September 10, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection. 2014. Strengthening Security of the VWP through Enhancements to ESTA. Updated November 4, 2014. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2008. Enhancing Security through Biometric Identification. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

---. 2018. NPPD at a Glance: Biometric Identity Management. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

---. N.d. FY 2022 Budget in Brief. Accessed September 10, 2021. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

U.S. Department of Justice. 2002. Budget Trend Data: From 1975 through the President’s 2003 Request to the Congress. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice. Available online.

---. N.d. U.S. Department of Justice Summary of Budget Authority by Appropriation. Budget document, U.S. Department of Justice, Washington, DC, accessed September 17, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service. N.d. Immigration and Naturalization Service: Budget Authority 1994-2003. Accessed September 10, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). 2014. ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations Report. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

---. 2014. Secure Communities Monthly Statistics through August 31, 2014. Washington, DC: ICE. Available online.

---. 2021. Delegation of Immigration Authority Section 287(g) Immigration and Nationality Act. Updated September 13, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. FY 2013 ICE Immigration Removals. Updated January 7, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. HSI International Week: International Ops: A Closer Look. Updated July 2, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Secure Communities. Updated February 9, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Student and Exchange Visitor Program. Updated March 24, 2021. Available online.

---. N.d. ICE HSI Visa Security Program. Accessed September 10, 2021. Available online.

White House. 2001. Joint Statement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States. News release, September 6, 2001. Available online.