You are here

An “Informal” Turn in the European Union’s Migrant Returns Policy towards Sub-Saharan Africa

Registration of Nigerian migrants for voluntary return. (Photo: Mariam Khokhar/IOM)

A not-insignificant share of the European Union’s resident irregular migrant population comes from sub-Saharan Africa. Even though estimates of the unauthorized population in EU Member States are notoriously imprecise, comparing the number of non-EU nationals (formally known as third-country nationals) ordered to leave with the number who departed suggests that the resident unauthorized population has grown by up to 3 million persons over the past ten years. And sub-Saharan African nationals accounted for around one-fourth of this growth, with a significant share coming from Nigeria (13 percent), Senegal (8 percent), and Eritrea (7 percent). Despite increased EU efforts in recent years to work with sub-Saharan countries to accept the return of their nationals, return rates remain low.

Amid publics increasingly anxious over migration, particularly since the 2015-16 crisis that saw hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers and economic migrants cross the Mediterranean, EU and national policymakers have placed new emphasis on deterring arrivals and stepping up the pace of returns.

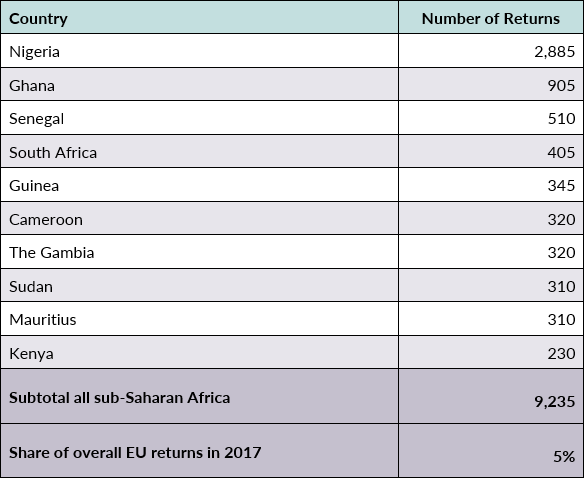

In 2017, EU countries carried out 189,545 returns of irregular migrants to third countries, of which 9,235 were to sub-Saharan Africa (see Table 1). The numbers remain small considering that only slightly more than one-third of non-EU nationals ordered removed actually were returned. The 2017 total was nearly 18 percent less than the number removed in 2016.

An initial focus by the European Union on formal readmission agreements with migrant-origin countries has given way since 2016 to informal ones. This article examines this informal turn and explores the potential effect that nonbinding readmission pacts could have on migrant returns to sub-Saharan Africa, challenging the assumption that such agreements will have a significant effect on future return levels agreed upon by EU and African policymakers. The analysis also evaluates EU reliance on return totals as an indicator of policy effectiveness and questions whether policy success can be quantified, considering data and other limitations.

The Framework for Returns

A decade after EU Member States agreed to establish common rules for managing the return of irregular migrants, European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker in his 2018 State of the Union address outlined a proposal for recasting the EU Return Directive to create a “stronger and more effective European return policy.”

This proposal reiterated the goal of increasing cooperation with origin countries, explicitly noting that it as a precondition for sustainably returning unauthorized migrants to their points of origin. Historically, the European Union and individual Member States have predominantly sought to ensure cooperation of origin countries by reaching readmission agreements, which broadly set out obligations and procedures to accept timely returns of irregular migrants and failed asylum seekers in exchange for favorable policies such as visa liberalization or financial incentives.

More recently, however, the European Union has quietly, yet significantly, changed its approach. Whereas the European Commission once exclusively sought formal readmission agreements, in 2016 it began to negotiate and conclude informal arrangements with third countries. The Commission’s 2018 proposal for a new EU Return Directive notes that “several legally nonbinding arrangements for return and readmission have been put in place.” The shift occurred as the Commission found great difficulty in finalizing formal accords with third countries, especially those whose populations rely on remittances from diasporas irregularly residing in Europe. Informal arrangements keep readmission deals largely out of sight, and thus take away domestic pressure on governments to refrain from cooperating on returns.

Sub-Saharan African State Returns

The European Union’s return and readmission policy has devoted particular attention to ensuring cooperation of sub-Saharan African states over the past two decades due to the very small number of returns of their nationals residing irregularly in Europe.

Table 1. EU Member State Returns of Third-Country Nationals to Top Sub-Saharan African Destinations, 2017

Source: Eurostat, “Third Country Nationals Returned Following an Order to Leave (Persons Returned to a Third Country) - Annual Data (Rounded) [migr_eirtn],” updated August 21, 2018, available online.

The European Union has repeatedly attempted to persuade sub-Saharan states to collaborate on return procedures. These efforts have materialized as joint texts agreed upon during a number of interregional dialogues (see Box 1). The common objective of working jointly on return and readmission procedures underlines these accords, as well as a focus on the reintegration of returned migrants. In theory, this would ensure timely and respectful return procedures between EU Member States and sub-Saharan countries.

Box 1. Europe and Africa: Interregional Dialogue and Return Procedures

Article 13 of the Cotonou Agreement, signed in 2000 by the European Union and the African, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) Group of States, stipulates that “each Member State of the European Union shall accept the return of and readmission of any of its nationals who are illegally present on the territory of an ACP State, at that State’s request and without further formalities; each of the ACP States shall accept the return of and readmission of any of its nationals who are illegally present on the territory of a Member State of the European Union, at that Member State’s request and without further formalities.”

The Valletta Summit on Migration (2015), bringing together African and European leaders, included the aim to “work more closely to improve cooperation on return, readmission, and reintegration.”

The 5th African Union-European Union Summit in Abidjan (2017) underlined “the importance of working jointly and swiftly on all aspects linked to irregular migration, in accordance with international law, the African Union Constitutive Act, its regulations and instruments, including return, readmission, and reintegration of own nationals in accordance with international law and standards, the principle of nonrefoulement, and applicable due international legal processes.”

In practice, however, these interregional pledges do not appear to have satiated EU return expectations. In its Fifth Progress Report on the Partnership Framework with Third Countries Under the European Agenda on Migration, the European Commission in 2017 noted:

- “Progress on returns from the EU [to Senegal] has been limited”

- “The return rate [to Mali] remains low and cooperation should be stepped up”

- “Cooperation on return from the EU [to Ethiopia] remains unsatisfactory, and the return rate is one of the lowest in the region.”

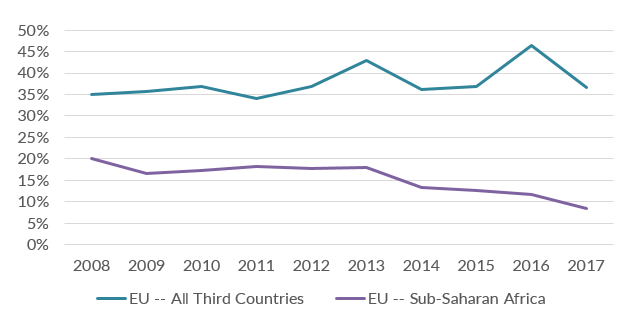

These observations are confirmed when looking at return numbers to sub-Saharan Africa between 2008 and 2017. The European Commission’s preferred calculation of “return rates”—the number of third-country nationals returned to their country of origin following an order to leave divided by the number ordered to leave—indicates that returns to certain sub-Saharan African countries are substantially lower than average return rates overall and actually show a downward trend.

Figure 1. EU Return Rates to Third Countries Overall and to Sub-Saharan Africa, 2008-17

Notes: Third-country nationals of countries mentioned under the “Sahel & Lake Chad” and “Horn of Africa” areas of the EU Trust Fund for Africa (Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal; and Chad, Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, The Gambia, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda) are taken into account in the calculation of return rates. Because of how Eurostat provides information on returns of third-country nationals, the return rate is based on data distinguishing returns by country of citizenship instead of destination country.

Sources: Eurostat, “Third Country Nationals Ordered to Leave - Annual Data (Rounded) [migr_eiord],” updated May 25, 2018, available online; Eurostat, ‘Third Country Nationals Returned Following an Order to Leave (Persons Returned to a Third Country) - Annual Data (Rounded) [migr_eirtn],” updated August 21, 2018.

However, it is important to note some of the limitations involved in the European Commission’s calculation of return rates, and in so doing underline that the numbers presented here should be treated with caution. Some experts also challenge the use of return rates to measure policy effectiveness.

Data Limitations

Firstly, as acknowledged by Eurostat, the EU data-collection service, there is the risk of double-counting return orders in multiple years, resulting in higher absolute numbers of third-country nationals ordered to leave and consequently, artificially lower return rates.

Secondly, the datasets used by the European Commission to calculate return rates encompass many dimensions that shape EU return procedures: voluntary and enforced returns, assisted and nonassisted returns, and returns to country of citizenship and country of transit, among others. However, these parameters do not fully capture or present all levels of granularity necessary to adequately describe return procedures. Following an evaluation of EU readmission agreements in 2011, Eurostat in 2014 began to collect more refined data on return procedures. It does so by differentiating the type of assistance received and type of agreement used, but EU Member States can submit their data on a voluntary basis, and inconsistent deliveries have thus far limited their potential to shift perspectives on measuring the effectiveness of the EU return policy.

An Inadequate Measure of Policy Effectiveness

Beyond the counts of returns ordered and accomplished, the data gathering does not shed light on the reintegration dimension of return procedures, an important component of readmission agreements. As such, information on the possible remigration of returned migrants or safeguarding of human-rights standards is not captured.

And, a narrow focus on return rates tends to overlook important contextual factors influencing effective return procedures, including logistical challenges that countries face when migrant flows increase. Take for example the struggles that EU Member States faced during the recent migration crisis; a combination of a lack of resources and central planning resulted in a mismanagement of migrant intake and ultimately integration. These problems have a potential impact on return procedures as well, and are overlooked by merely assessing the effectiveness of return procedures in relation to return rates.

Formal Struggles Lead to Informal Adaptations

The European Commission to date has reached only one legally binding formal readmission agreement with a sub-Saharan African country: Cape Verde in 2013. The Commission started negotiations with Morocco (2000), Algeria (2002), and Nigeria (2016), but those were not concluded.

Given the disappointing movement on finalizing formal agreements in sub-Saharan Africa and beyond, the turn towards informality was to be expected. These informal accords vary greatly in terms of formats and content, ranging from administrative arrangements setting out standard operating procedures to commitments of cooperation in return procedures, such as memoranda of understanding (MOUs) and joint statements. Some examples include the Joint Way Forward on Migration Issues Between Afghanistan and the EU (2016) and the EU-Bangladesh Standard Operating Procedures for the Identification and Return of Persons Without an Authorization to Stay (2017).

The European Commission recently has concluded a flurry of informal readmission agreements with sub-Saharan countries, including arrangements with Guinea in 2017, and in 2018 with Ethiopia, The Gambia, and Côte d’Ivoire. A leaked document on Draft Admission Procedures for the Return of Ethiopians from European Union Member States offers a roadmap for informal arrangements. The document outlines plans to adopt nonbinding commitments to improve cooperation in return procedures, with specific attention being paid to joint efforts on the issuance of travel documents, the reintegration of returned migrants, and the regular evaluation of implementation.

However, the content of what has been agreed remains largely unclear due to the informal nature of these arrangements. This, in turn, has drawn frequent criticism from advocates, academics, and members of the European Parliament, as they point out that informal readmission agreements inherently challenge principles of democratic and judicial accountability. This critique comes on top of accusations that these informal accords insufficiently guarantee compliance with European and international human-rights standards. Moreover, there are serious concerns about the intertwinement between asylum procedures, return procedures, and the designation of safe countries of origin. No agreement elucidates this concern more than the EU-Afghanistan deal, which has been sharply criticized by human-rights groups and others for allowing individual Member States to return Afghan nationals, including children, to a country where serious instability and violence remain features of everyday life. As a result, important questions are being raised as to which countries could theoretically cooperate under EU informal readmission agreements.

National-Level Solutions

Current EU efforts to strike informal readmission agreements with sub-Saharan African countries strongly echo long-established, similar initiatives on the national level. Though it is too early to evaluate recently finalized informal readmission agreements between the European Union and sub-Saharan states, a look at the results from previous bilateral accords can provide insight into how the relationship between informal readmission agreements and return numbers should be understood. It is important to note, however, that since a comprehensive overview of informal readmission agreements between EU Member States and sub-Saharan states does not exist due to the unofficial character of these deals, the subsequent analysis is limited to a case-by-case review.

The Norway-Ethiopia Informal Agreement

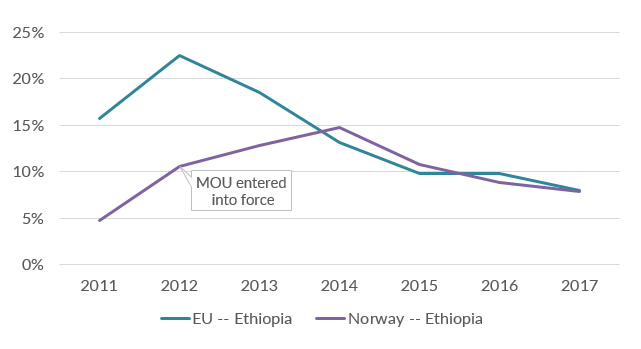

The MOU struck between Norway and Ethiopia in 2012 offers one example. Its objective was “to lay down the basis for a closely coordinated, phased, dignified, and humane process of assisted return of Ethiopian nationals in Norway with respect primarily to voluntary return and the importance of safe and dignified return and sustainable reintegration.” Interestingly, the agreement shows some similarities with the informal EU-Ethiopia readmission accord concluded in 2018, in particular with regard to its focus on practical cooperation and attention to reintegration.

It appears that implementation of the Norway-Ethiopia deal has not had a substantial effect on returns. At its peak, in 2014, 15 percent of those ordered returned to Ethiopia actually did leave—a rate comparable to the overall EU return rate to Ethiopia in the absence of a readmission agreement. The return rate from Norway to Ethiopia dropped to 8 percent in 2017, down from 11 percent in 2012, when the deal was signed.

Figure 2. Return Rates Between Norway-Ethiopia and EU-Ethiopia, 2011-17

Sources: Eurostat, “Third Country Nationals Ordered to Leave - Annual Data (Rounded) [migr_eiord],” updated May 25, 2018; Eurostat, “Third Country Nationals Returned Following an Order to Leave (Persons Returned to a Third Country) - Annual Data (Rounded) [migr_eirtn],” updated August 21, 2018.

Informal Agreements by the United Kingdom

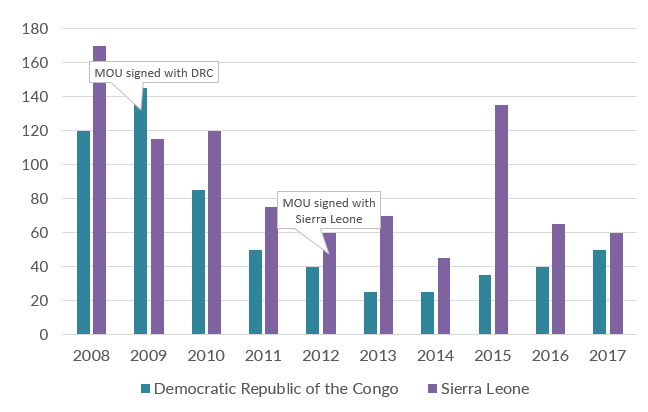

A second example involves the United Kingdom, which finalized MOUs with Nigeria (2005), Angola (2007), Somaliland (2007), Rwanda (2008), Democratic Republic of the Congo (2009), Sierra Leone (2012), and South Sudan (2013). Even though these agreements have been around for some time, data limitations make it possible to review return numbers only for the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sierra Leone. The number of Congolese and Sierra Leoneans returned from the United Kingdom has not substantially changed following the entry into force of the informal readmission agreements, even considering varying levels of total returns ordered on an annual basis.

Figure 3. Third-Country Nationals Returned from the United Kingdom to the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sierra Leone, 2008-17

Note: As noted by Eurostat, “[UK] statistics on ‘third-country nationals returned’ should not be considered as a subset of the statistics on ‘third-country nationals ordered to leave’ from the same year,” thus rendering impossible an analysis of return rates.

Sources: Eurostat, “Third Country Nationals Returned Following an Order to Leave (Persons Returned to a Third Country) - Annual Data (Rounded) [migr_eirtn],” updated August 21, 2018; Eurostat, “Enforcement of Immigration Legislation (migr_eil), Annex 2 EIL data completeness,” updated April 30, 2015, available online.

The results of the Norwegian and British bilateral agreements seem to suggest that the effect of informal readmission agreements on return rates may be, at best, limited.

What to Expect from Future Informal Readmission Agreements

The finalization of informal readmission agreements by the European Union with unauthorized migrants’ countries of origin seems promising, on paper, in ensuring cooperation for return. However, this approach as a cornerstone of a stronger and more effective European return policy appears to be less promising when one reviews the available data. Considering the underwhelming results of informal return agreements at the national level, it would be wise to not overemphasize the effects these informal EU readmission agreements can have in terms of ensuring higher return rates, and instead view them as products of broader migration relations. Crucially, adopting a wider definition of effectiveness that looks beyond mere return rates could bring in fresh perspectives shedding light on what could constitute a successful EU returns policy.

The author thanks Nils Coleman of the Dutch Ministry of Justice and Security for providing valuable feedback during the research stage.

Sources

African Union - European Union. 2017. Joint Declaration of 5th African Union - EU Summit. Press release, November 30, 2017. Available online.

Cassarino, Jean-Pierre. 2007. Informalising Readmission Agreements in the EU Neighbourhood. The International Spectator 42 (2): 179-96.

Council of the European Union. 2017. Draft EU-Gambia Good Practices for the Efficient Operation of the Return Procedure. ST 12822 2017 INIT, October 10, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. Admission Procedures for the Return of Ethiopians from European Union Member States. 15762/17, December 18, 2017. Available online.

European and African Heads of State and Government. 2015. Valletta Summit, 11-12 November 2015 Action Plan. Press release, November 12, 2015. Available online.

European Commission. 2011. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: Evaluation of EU Readmission Agreements. COM(2011) 76 final. News release, February 23, 2011. Available online.

---. 2017. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, and the Council: Fourth Progress Report on the Partnership Framework with Third Countries Under the European Agenda on Migration. COM(2017) 350 final. June 13, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, and the Council: Fifth Progress Report on the Partnership Framework with Third Countries Under the European Agenda on Migration. COM(2017) 471 final. September 5, 2017. Available online.

---. 2017. Commission Decision of 8.9.2017 on the Signature of the EU-Bangladesh Standard Operating Procedures for the Identification and Return of Persons Without an Authorisation to Stay. ST 12031 2017 COR 1, September 8, 2017. Available online.

---. 2018. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on Common Standards and Procedures in Member States for Returning Illegally Staying Third-Country Nationals (Recast). COM(2018) 634 final. September 12, 2018. Available online.

---. 2018. A Stronger and More Effective European Return Policy. Fact sheet, European Commission, Brussels, September 13, 2018. Available online.

European Commission, Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs. 2017. Letter to Mr. Claude Moraes, MEP: EU Readmission Developments – State of Play October 2017. November 14, 2017.

---. 2018. Return and Readmission. Updated April 10, 2018. Available online.

European Migration Network. 2014. Synthesis Report: Good Practices in the Return and Reintegration of Irregular Migrants: Member States’ Entry Bans Policy and Use of Readmission Agreements Between Member States and Third Countries. Brussels: European Migration Network. Available online.

European Parliament, Policy Department for Citizens' Rights and Constitutional Affairs. 2018. The Implications of the United Kingdom’s Withdrawal from the European Union on Readmission Cooperation. February 6, 2018. Available online.

Eurostat. 2015. Enforcement of Immigration Legislation (migr_eil). Updated April 30, 2015. Available online.

---. 2015. Enforcement of Immigration Legislation (migr_eil), Annex 2 EIL data completeness. Updated April 30, 2015. Available online.

---. 2015. Enforcement of Immigration Legislation (migr_eil), Annex 3 EIL Technical Guidelines. Updated April 30, 2015. Available online.

---. 2018. Third Country Nationals Ordered to Leave - Annual Data (Rounded) [migr_eiord]. Updated May 25, 2018. Available online.

---. 2018. Statistics on Enforcement of Immigration Legislation. Last updated June 2018. Available online.

---. 2018. Third Country Nationals Returned Following an Order to Leave (Total Number of Persons Returned)–Annual Data (Rounded) [migr_eirtn]. Updated August 12, 2018. Available online.

European Union and African, Caribbean, and Pacific Group of States. 2000. Regulation (EU) No. 22000A1215(01) of the European Community and its Member States: Partnership Agreement Between the Members of the African, Caribbean, and Pacific Group of States of the One Part, and the European Community and its Member States, of the Other Part, signed in Cotonou on June 23, 2000. OJ L 195, August 1, 2000. Available online.

European Union and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan. 2016. Joint Way Forward on Migration Issues Between Afghanistan and the EU. October 4, 2016. Available online.

European Union and the Republic of Cape Verde. 2013. Regulation (EU) No. 22013A1024(02): Agreement Between the European Union and the Republic of Cape Verde on the Readmission of Persons Residing Without Authorisation. L 282/15, October 24, 2013. Available online.

Governments of Ethiopia and Norway. 2012. Memorandum of Understanding Between the Government of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia and the Government of the Kingdom of Norway. January 26, 2012. Available online.

Modern Ghana. 2016. Mali Denies Agreement on Failed EU Asylum Seekers. Modern Ghana, December 19, 2016. Available online.

Molinari, Caterina. 2018. The EU and its Perilous Journey Through the Migration Crisis: Informalisation of the EU Return Policy and Rule of Law Concerns, 2018. Available online.

Rasmussen, Sune Engel. 2016. EU Signs Deal to Deport Unlimited Numbers of Afghan Asylum Seekers. The Guardian, November 3, 2016. Available online.

Sargentini, Judith. 2018. Question for Written Answer to the Commission: Agreement Between the EU and Ethiopia on Return Procedures. February 15, 2018. Available online.

Save the Children. 2018. From Europe to Afghanistan: The Experience of Child Returnees. Save the Children and Samuel Hall. Available online.

Wagner, Fabian. 2018. EU Deportations Risk Further Destabilizing Mali. Refugees Deeply, July 2, 2018. Available online.