You are here

Migration in the Netherlands: Rhetoric and Perceived Reality Challenge Dutch Tolerance

Amsterdam, the Netherlands. (Photo: Felix Winkelnkemper)

Over the past two decades, the Netherlands has gone from the forefront of multiculturalism to witnessing a rise in far-right populism—with immigration, and a focus on Islam, at the heart of this shift. Where the government and population once handled immigrant integration with famed Dutch tolerance, some have grown deeply intolerant of newcomers, equating immigration with a rise in religious extremism and terror, and a loss of prosperity.

These fears do not, however, necessarily reflect the facts in a country where population growth largely relies on net immigration, while both immigration and emigration are at high points, and some sectors—including agriculture and heavy industries—largely depend on migrant workers. Nor do the fears align with a country whose vibrant cultural, sporting, and business life is replete with active and engaged refugees and immigrants.

The main categories of arrivals in recent years have been family migrants, asylum seekers, and European Union citizens. Contemporary debate has centered on topics such as dealing with children who have lived in the Netherlands in irregular status for more than five years, limiting asylum-seeking arrivals while doing more through humanitarian assistance, the place of Islam in a European society (including education in Islamic schools), the advisability of dual nationality, and flowing from all this, the nature of Dutch society.

Several incidents underlie the fears held in some parts of the Dutch populations concerning immigration. These include the post-9/11 fallout across the world, as well as events in the Netherlands, such as the rise and subsequent 2002 assassination of anti-immigration politician Pim Fortuyn and the 2004 murder of filmmaker Theo van Gogh by a Dutch-born Muslim of Moroccan origin. More day-to-day concerns of some that jobs might be taken by immigrants willing to work for lower wages, or that the welfare system might be abused add to these anxieties.

Far-right populists prey on and promote these anxieties, yet for all their prominence in portrayals of contemporary politics in the Netherlands, these populists have not become as powerful as many outside the country seem to presume, nor have they entered government, as has occurred elsewhere in Europe. The multiparty system (as of 2017 there were 13 political parties represented in Parliament) with proportional representation is largely responsible for that, along with the fact that mainstream parties recognize the long-term danger of working too closely with the extremes. Prominent politicians who espouse anti-immigrant rhetoric include, most notably, Geert Wilders, the leader of the far-right Freedom Party (PVV), which captured the second-largest number of seats in Parliament in the 2017 election, and the more recent alt-right star, Thierry Baudet. However, while these politicians’ words influence debate, their parties have not been able to join governing coalitions.

People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD) Prime Minister Mark Rutte expressly ruled out working with Wilders’ PVV no matter the outcome of the 2017 elections and stood by that despite the PVV gaining the second-largest number of seats. Similarly, as the Baudet-led Forum for Democracy (FvD) became the largest party in three provinces in March 2019 elections, other parties in at least one province have refused to work with the FvD, meaning they cannot achieve the local coalitions necessary to actually gain power.

The third government led by Rutte, a center-right one, emerged from the longest coalition negotiations ever recorded in the Netherlands—lasting 209 days beyond the March 2017 parliamentary elections—after initial negotiations with GroenLinks (Green Left) collapsed over Rutte’s more restrictive immigration policy. Even two years after the election, ambitious policies such as “reception in the region” remain standpoints promoted at the EU level, rather than reality, while policy on immigrant integration is expected only to deepen the difficulties faced by refugees in particular. Political developments and popular discourse during the 2017 government’s term demonstrate the tension between the Netherlands’ moderate forces, suggesting that tolerance counts only for compatriots and can only go so far. Many higher-level policy changes depend on external as much as internal factors, although how policy is implemented and the precise handling of immigration and asylum cases, as well as integration approaches remain national, sovereign matters and very much in the Dutch government’s hands.

This country profile explores historical and contemporary migration to the Netherlands, as well as how contemporary policymaking has been challenged, and somewhat shaped by an electoral shift to populism.

A Historical Haven under Pressure

Since the 16th century, the Netherlands has had a reputation as a humanitarian haven, with refugees and immigrants attracted by Dutch tolerance and prosperity. Famously welcoming to the Huguenots, religious and political refugees fleeing France in the 17th century, this seafaring nation was always open when called upon to protect.

During World War I, up to 900,000 Belgians fled to the neutral Netherlands. Most of them returned following the end of conflict. In the 1930s, many Jews and other refugees arrived from Germany and Austria, and by 1940 there were about 20,000 refugees from those two countries in the Netherlands. With Germany invading in 1940 and placing the Netherlands under occupation, these refugees had to either move on or risk perishing during the war. Most did not survive.

Colonial Ties and “Temporary” Workers

After World War II, immigration resulting from the Dutch colonial heritage began, including Dutch returnees and the descendants of those who had lived and worked in Indonesia, Suriname, and the Caribbean. Between 1945 and 1965, some 300,000 people (180,000 of whom were Eurasians) moved from Indonesia to the Netherlands. Migration from Suriname after its independence in 1975 was less significant in scale.

The Dutch Antilles and Aruba also form part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands; the people from those islands have Dutch nationality, yet their arrival in the Netherlands is widely viewed by the Dutch public as immigration.

Between the end of World War II and the oil crisis that hit in 1974, the Netherlands, like other Western European states, received guest workers through labor recruitment programs. These workers came primarily from Mediterranean countries, including Italy, Spain, Turkey, Morocco, and Yugoslavia. Their migration was intended to be temporary, but in many cases was not. After 1975, the major migration flows from these countries were for family reunification and formation (except for refugee arrivals from the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s).

Postwar and Current Humanitarian Arrivals

From 1945 to the early 1980s, relatively few refugees arrived. Those who did were mostly resettled, rather than being asylum seekers who applied for protection after arrival. Some who might have sought asylum simply joined the ranks of economic migrants until 1974, when the consequences of the oil crisis brought greater restrictions to labor migration, making asylum their only route. Between 1978 and 1983, the number of people seeking asylum hovered around 1,000 per year. By 1985, it had grown to more than 4,500, enough for the government to change its approach to humanitarian protection. The goal was to keep resettlement at around 500 annually while developing a system to process spontaneous arrivals, facilitating identification of bona fide asylum claims.

Annual asylum seeker applications peaked at more than 45,000 in 1998, with a majority of applicants fleeing the Yugoslav wars; resettlement arrivals meanwhile dropped into the dozens. After managing the significant number of asylum seekers during the 1990s using temporary protection measures, and following the imposition of restrictions, arrivals fell to less than 10,000 in 2004; meanwhile, resettlement received renewed attention. A quota program to resettle 500 refugees yearly was established, and subsequently expanded to 750 in the 2017 coalition agreement. When the Dutch commitment to accepting refugees under the EU-Turkey deal and intra-EU relocation are added, some 3,000 places were available in 2018. While these numbers are relatively small in the face of global resettlement needs, they follow an upward trend.

With vast inflows of asylum seekers and migrants in Europe in 2015 and 2016, fueled in part by the Syrian civil war, asylum-seeker arrivals in the Netherlands rose again, as did overall immigration after a short period of net migration levels below zero. Nearly 44,000 asylum requests were lodged in the Netherlands in 2015—a recent peak, though still fewer than those filed in 1998. Syrians formed the largest group, with roughly 18,700 claims, followed by Eritreans, with about 7,400. Asylum claims dropped to 19,370 in 2016 and 16,145 in 2017, before rising again slightly in 2018 to 20,510. The largest groups continued to be Syrians, Iranians, and Eritreans. The increase in the number of asylum applications from Turks and Algerians is notable, as well as the entry of Moldovans and Yemenis to the top ten countries of origin. Meanwhile, claims from Iraq and Albania are trending down.

Although asylum applications have declined from their recent 2015 high, the number of family members of asylum seekers arriving within three months after the application was approved, for at least a limited protection period, has been trending up. In 2015, 13,800 family members arrived, up from 11,815 in 2016 and down from 14,490 in 2017, followed by a marked drop to 6,465 in 2018. Since 2016, Dutch authorities have started very strictly applying evidentiary rules regarding family relationships. This has posed challenges for asylum seekers, particularly Eritreans, for whom access to documents can be very difficult. Some, such as the Dutch Refugee Council, argue that the application of the rules is not in line with the EU directive on family reunification, which states that an application for family reunification cannot be denied solely on the basis of insufficient documentation.

In the Dutch Caribbean, arrivals of Venezuelans seeking humanitarian assistance in Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao have been notable from 2015 onwards. Many arrive by boat and remain without documentation on the islands. How many Venezuelans are on the islands is unknown, yet 200 applied for asylum in Aruba in the first two months of 2019, overwhelming the limited asylum system. Some 16,000 Venezuelans, most unauthorized, were believed to be on Curaçao in late 2018, and a similar number on Aruba. Eighty-eight Venezuelans were rescued at sea in 2015, rising to 326 in 2017, and 91 in the first five months of 2018, demonstrating the steady rise in attempts to leave the country. Although there were calls for the Dutch government to step in to assist the island governments with asylum claims and ensure rights were upheld in territories unused to dealing with so many arrivals, the government in the Hague declined to do so.

Population Growth Fueled by Immigration

The Netherlands is one of the most densely populated countries in the world, with nearly 509 people per square kilometer in 2017, according to World Bank estimates—and trending upward. It is the most crowded EU Member State, other than the island nation of Malta. The high population density has a mixed sociological impact. Close proximity to others can lead to a high level of tolerance and compromise among groups, according to some sociologists, while other historians and philosophers point to the aftermath of the 17th century religious wars and subsequent reformation as the roots of Dutch religious tolerance. At the same time, any behavior outside the generous realms of what is considered “normal” is immediately visible and can give rise to strong reactions. Both the presence of outsiders who do not (or seem not to) adapt and the rise of voices opposed to others on ethnic, racial, or religious grounds, could be said to challenge the balance.

At the beginning of 2018, nearly 17.2 million people lived in the Netherlands, 12 percent (or about 2.1 million) of them foreign born, according to Statistics Netherlands. Amid aging populations and low birthrates, consistent with trends elsewhere in Europe, Dutch population growth in the past decade has been largely fueled by immigration. After five years of negative net migration between 2003 and 2008, the figures have gradually risen, nearing the peak levels last seen in the mid-1970s.

The Netherlands experiences four main streams of immigration: asylum seeker and family reunification arrivals; intra-European Union migration, in particular from Poland; and, as a remnant of the country’s history as a major colonial power, longstanding migration from the Caribbean parts of the kingdom.

Meanwhile, the Netherlands’ traditionally high level of emigration, which continues today, runs counter to demographic predictions and the norm in Western European countries, and has caused concern among politicians and the media. One 2008 study cited the high population density and the political climate as the major reasons many Dutch were either dreaming of leaving or actually doing so. The last major wave of emigration occurred about 50 years prior, during the postwar period. For a few years in the early 2000s, the migration balance was negative, as emigration outstripped immigration. Net immigration is the driver for population growth. Meanwhile, mid-2017 UN estimates indicate slightly more than 1 million Dutch citizens live abroad, while campaigners for dual-citizens’ rights, under the rallying cry “Once Dutch, Always Dutch” suggest a range of between 700,000 and 1.2 million expatriates in 2015. Those abroad claiming some degree of Dutch ancestry might number closer to 15 million (and some of these might have claims to nationality).

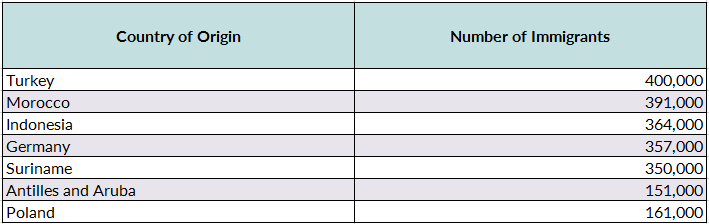

The immigrant-background share of the Dutch population and its diversity have grown in recent years. When considering both immigrants and Dutch natives who have at least one parent born outside the Netherlands, the migrant-origin share of the population stood at 23.1 percent in 2018. Of the nearly 4 million people with a migrant background, roughly 2 million are from non-Western countries (see Table 1). This figure has almost doubled since 1996.

Table 1. Top Migrant-Background Groups in the Netherlands, 2015

Note: "Migrant background" includes both immigrants and the Dutch born who have at least one parent born outside the Netherlands.

Sources: Central Statistical Office (CBS), “Bevolking naar migratieachtergrond,” news release, November 21, 2016, available online; CBS, “Bevolking, huishoudens en bevolkingsontwikkeling; vanaf 1899,” statistics table, updated December 29, 2017, available online; CBS, “Bevolking; generatie, geslacht, leeftijd en migratieachtergrond, 1 januari,” statistics table, updated May 14, 2018, available online; CBS, “Bevolking; kerncijfers,” statistics tables, updated October 30, 2018, available online.

In 2015, nearly 22,000 people received a residence permit in the Netherlands for family reunification, the largest groups being Indians and Turks, with about 2,000 permits each. Some 13,845 people arrived for family reunification with asylum seekers. While prior to 2004, family channels had been the primary source of immigration, the number dropped following implementation of stricter rules. However, since 2007 family-based immigration has increased from Eastern Europe and top origin countries of labor migrants and asylum seekers. In 2018 the number of people arriving for family reunification with asylum seekers dropped for the first time in several years, to 6,465.

Over the last decade, labor migration has overtaken family reunification as the main pathway for newcomers. Almost 80 percent of labor migrants are EU nationals, while 10 percent are from Asia. Foreign student enrollment has also increased significantly, primarily from Germany, followed at a distance by China. The total number of students has risen from 28,000 in academic year 2004-05 to 112,000 in 2016-17, and students hail from 163 different countries. The 2017 governing coalition agreement recognized the need to bring in highly skilled workers, to maintain the Netherlands’ innovation and creative “edge”—but the language strongly implies that this flow will be limited, and targeted only at the most qualified.

In 2018, 20,510 first-asylum applications were lodged in the Netherlands, an increase from 16,145 a year earlier, but nowhere near the 2015 high of 43,095.

Government estimates of the number of unauthorized immigrants, which by nature are imprecise, have gone down since the EU enlargements of 2004 and 2007. Around 100,000 immigrants are now estimated to be living in the country in irregular status.

Citizenship: Once Dutch, Always Dutch?

The issue of naturalization, and dual citizenship in particular, has emerged as a sticking point in Dutch debates. The general rule is that dual nationality is not permitted, with exceptions such as when a person is born with Dutch and another citizenship. The Netherlands practices both jus sanguinis (citizenship passed from parents) and a limited form of jus solis (“double” jus solis, whereby citizenship is acquired by children born in the Netherlands to parents who were also born in the Netherlands, even if the parents do not have Dutch citizenship themselves).

Dutch nationals who take on another citizenship generally have to give up their Dutch passport; most of those who become Dutch through naturalization must surrender their other nationality, where permitted by law—with some key exceptions. Dual nationality has become a thorny question, in part because there are some countries (e.g. Morocco) where it is forbidden to renounce citizenship. Politicians on the far right consider “citizenship” to be synonymous with “loyalty,” as was revealed in their demands that no one with dual nationality be appointed to a ministerial post in the 2017 cabinet (in fact one minister is a dual Dutch-Swedish national, a junior minister also holds Croatian citizenship, and the Speaker of Parliament also has Moroccan nationality). Other parties, including coalition partner D66, see this very differently.

A major element in the origin of this discussion is the fact that the countries in question are often Muslim countries. However, another case has arisen to consider dual nationality positively, namely Brexit. Both Dutch citizens currently in the United Kingdom and British citizens in the Netherlands would, some argue, benefit from the possibility to naturalize, if their situation permits it, before the United Kingdom leaves the European Union, and be allowed to keep both nationalities. Largely motivated by Wilders’ rhetoric and reactions to it, the default approach of the earlier government (2012-17) led by Rutte was to oppose dual nationality. The Rutte-led coalition government formed in 2017 signaled its readiness to consider modernizing the nationality law, especially in light of Brexit, with proposed changes including greater generosity in accepting multiple nationalities for first-generation immigrants and emigrants, while establishing a point at which subsequent generations must choose just one nationality. Indeed, in April 2019 a politician from the coalition partner CDA recognized publicly that political opposition to dual nationality is a domestic focus that is (perhaps unintentionally) to the detriment of Dutch citizens overseas.

Between 2015 and 2018, about 28,000 immigrants per year became Dutch citizens, a decrease from the roughly 33,000 naturalizations in 2014. It is likely that some of these people became dual citizens, maintaining their original nationality, if the laws of both countries permitted it. In addition, an unknown number of children were born to at least one Dutch parent outside the Netherlands, and automatically became Dutch citizens, possibly in addition to at least one other nationality. As such, this issue impacts many among the approximately 1 million Dutch nationals around the world, who might have spouses and children of multiple nationalities.

A Focus on Migrant Children

Migrant children have been the focus of significant policy developments and concerns for several years. There are two specific aspects of this that return in debate and attract significant media and public attention: regulations for children who have lived in the Netherlands for five or more years without documentation and the role of religious (Islamic) schools in society.

In 2012 the VVD-PvdA (Labor Party) coalition government established a Children’s Amnesty (Kinder Pardon) regulation, in essence amnesty for children who had lived without legal status in the Netherlands for five or more years. The reasoning behind this was that children who had sought asylum together with their parents but had been rejected through all appeal levels, had been in school in the Netherlands, and spoke Dutch would generally find it difficult to adapt or acculturate to society if returned to their country of origin, particularly if the socioeconomic situation there was vastly different from that of the Netherlands. Although the regulation on paper was sufficient to regularize the status of families in this situation, very few in reality achieved legal status, as a 2017 report by the Children’s Ombudsman detailed.

It was the situation of an Armenian brother and sister that eventually drew public outcry and led to a new agreement. Lili and Howick were set to be deported to Armenia after 11 years in the Netherlands, where their asylum claims had been rejected. Their mother had previously been deported, but according to experts was not of sufficient mental health to be able to care for the children, who would be going to a country they did not know, with a language they did not understand, and into a deprived socioeconomic situation—all of which in principle should have been grounds to exclude their removal under the existing regulation. After several dramatic turns with the children running away and going into hiding to avoid imminent deportation, all closely followed and reported by the mainstream media, they were granted legal status.

As a result of this case, a new Children’s Amnesty regulation was determined through broad political compromise. However, demonstrating the focus on numbers and intense difficulties in the immigration debate in the Netherlands, as part of this compromise, the resettlement program was dialed back from 750 places to 500 in February 2019.

Another touchpoint in the ongoing integration debate is the role of Islamic schools, both those offering regular, full-time education and weekend schools teaching culture and language. An Islamic foundation in Amsterdam opened a secondary school in 2017, after a fraught permitting process, but in accordance with Dutch freedom of education laws and receiving Amsterdam City Council subsidies. In 2019 the National Coordinator for Security and Counterterrorism warned the City Council that pupils at the school were being influenced by teachers who are in contact with terrorists, causing subsidies to be frozen.

Weekend schools have also raised concern. Media reports in 2018 suggest Syrian parents had established a dozen weekend schools, teaching their children the language and culture of their homeland. There is some fear that these schools are also teaching religion and the Islamic cause in such a way as to influence these children towards potential terrorism, and at the very least that such schools hamper the integration of the children into Dutch society (although there are no similar concerns for the thousands of Dutch weekend schools worldwide, which teach the language and culture to children either of families who will/might return to the Netherlands or who have Dutch heritage). As many Syrian families have only temporary residence permits, it is not clear that long-term integration is something for which they can plan. Meanwhile, the Turkish government is subsidizing 12 Turkish weekend schools in the Netherlands, which are not under Dutch government supervision, as weekend schools generally are not. However, with the involvement of foreign government support, there are calls for a different approach to ensure these schools are meeting Dutch standards and in particular that they do nothing to discourage or prevent integration.

Cities on the Frontline

Many of the schools in question are in major cities, and cities find themselves on the frontline of the implementation of integration plans. Communities and municipal councils are responsible for the day-to-day work of providing integration courses and housing for asylum seekers and refugees, among other activities directed at newcomers. At the local level, the impact of anti-immigrant policies and the pressure to integrate without genuine support is seen and felt by people who are in daily contact with immigrants and see the difficulties they face. While tensions have arisen in some communities, with people living near (proposed) reception centers sometimes expressing frustration about their fears for public safety, municipal leaders have promoted mutual understanding and a duty to help protect people who escaped persecution and violence, and give them a new home.

Indeed, despite concerns about the rising popularity of anti-immigrant and anti-Muslim stances, the broader Dutch public remains committed to upholding the country as a rights-respecting, tolerant one. Support for accepting recognized refugees remains strong, arguably as strong as or stronger than the belief that the Netherlands should reject those who would abuse Dutch generosity or not quietly make the effort to adjust to Dutch society. That such support exists is exemplified by the fact that, as of 2018, 14,000 people were active volunteers with the Dutch Refugee Council, just one of several organizations assisting refugees in the Netherlands.

Amsterdam’s much-admired Mayor Eberhardt van der Laan, who died in 2017, frequently spoke of his vision for improving understanding and opening more spaces for refugees in the city, and the esteem in which this local politician was held nationally did much to allow people to feel that their ongoing tolerance of and support for newcomers is appropriate. Thus, the perspective of towns and cities on immigration and integration is significantly different from those that seem to prevail at the national level, representing how on the local level immigration is more accepted than national and international debate might suggest.

In spite of this, the presence of dual nationals has posed some challenges for cities, and in at least one case sparked an international diplomatic incident. Ahead of the April 2017 Turkish constitutional referendum to expand President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s powers, Dutch-Turks in Rotterdam planned a political rally in support of the move and invited several Turkish ministers. Wilders and his supporters strongly oppose Turkish political events in the Netherlands, and Rutte—just days before the Dutch general election—banned the officials from landing in Rotterdam and taking part in the gathering.

One Turkish minister who was already in Germany took advantage of free movement within the Schengen area to travel to Rotterdam by car, where she was intercepted by Dutch police outside the Turkish consulate. She remained in her vehicle for several hours, until Dutch police lifted her car onto a flatbed truck and removed her, with the vehicle, back to Germany.

Migration and Refugee Issues: The 2017 Coalition Agreement

The 2017 coalition agreement marked the first major opportunity to adjust Dutch refugee policy based on the lessons learned from the significant arrivals in the Netherlands and Europe more broadly in 2015-16. The policy goals largely reflect the coalition’s broader pull to the right, and the effort to deal with the perception of stronger anti-immigrant sentiment. Many of the goals draw on unachieved ambitions of Dutch governments over the last decade or more, calling for a conceptual transformation of the global or regional approach to migration. But a conceptual shift alone cannot change the realities of individuals’ choices or journeys.

For at least two decades, the Dutch position has been that immigration and asylum are European issues requiring European solutions. If there was a crisis in 2015, it was a crisis of European policy—of solidarity in the face of high numbers of migrant and asylum-seeker arrivals, and of common policy to deal with those arrivals in a unified, European way. Successive Dutch governments have advocated for solutions that get to the roots of mass displacement, including addressing refugee reception capacity in regions of origin and the poverty and conflicts that give rise to migration in the first place. The 2017 coalition reiterated these approaches, which may hold some promise in the long run, but require both significant financial resources and enormous diplomacy. In 2018, the coalition issued a plan to implement the strategy, at home, in Europe, and beyond.

Development Assistance

The coalition said it planned to increase the share of the national budget devoted to development assistance, targeting for improvement protection capacity in regions of origin. Improving education for refugee children will be a key area of focus, alongside creating employment opportunities for refugees. Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and a selection of African countries top the list for target locations. However, annual budgets since 2017 have shown no actual increases in development aid funding.

The Dutch government also hopes to develop more agreements with countries closer to origins of crisis and displacement, modeled on the 2016 EU-Turkey agreement, which combined support for refugee protection in Turkey with limited EU resettlement places for Syrians. Whereas many commentators have proclaimed the EU-Turkey deal ineffective, or at best helped by circumstances, the European Commission, including Dutch First Vice President Frans Timmermans, are convinced it has worked. Indeed, Timmermans has pushed the Dutch coalition partners to work on reaching more such deals in the future—a wish that was taken up in the coalition agreement, but which needs collaboration from EU partners to become a reality.

Indeed, much of the Dutch government’s plan is based on the hope of finding a coherent, EU-wide approach to reducing irregular migration. The philosophy laid out in the coalition agreement strongly implies that following the implementation of such a strategy, “real refugees” will all find suitable solutions close to home, meaning that any who request asylum in the Netherlands can likely be returned to a place closer their origin that the Dutch deem safe.

Integration

Regarding immigrants already in the country, though the coalition partners clearly state their opposition to discrimination based on someone’s country of origin, they also make a strong distinction between the rights of Dutch citizens and those of refugees and immigrants. Lawyers point out that while a discrepancy between nationals and nonhumanitarian immigrants might be permitted, under international law there should not be any difference in the rights of nationals and recognized refugees. However, the coalition has signaled it plans to cut the rights of people granted asylum during their first years in the country. It is not clear how this would help them to integrate.

The agreement also emphasizes the need for refugees and immigrants to be proactive in their integration—at the risk of either losing a residence permit (for immigrants), or for those granted short-term protection of not gaining additional relief, if they do not. A variety of educational channels are available to assist newcomers in acquiring Dutch language proficiency and knowledge of local systems, and the government has moved to develop an active diversity and antidiscrimination policy targeting public-sector employment.

Reception and Removal

The overall message the coalition has put forth is that the Netherlands would prefer to keep migrants and refugees in their regions of origin; it will deal with them according to EU agreements in the event they arrive in the Netherlands, but will critically evaluate all asylum claims and work toward returning those deemed not in need of protection. Under the coalition agreement, eight reception centers across the Netherlands will house rejected asylum seekers who agree to cooperate in being returned to their country of origin within two months. If they do not cooperate, they can be removed from the center (and thus not provided housing and food). Local authorities may also arrange their own, more minimal reception facilities to house such migrants for a few days, but cannot offer longer-term solutions. While the government’s emphasis is on how sober these conditions will be, describing them as the provision of only “a bed, a bath, and some bread,” the immediate response to the plan from Wilders was that the provision of such accommodation would only attract more migrants from Africa in particular. This perhaps demonstrates how no matter the steps taken to cut services or narrow access for migrants, the rhetoric will, so long as the populist voice is strong, always say it is too much, too kind, too open.

The Rise and Role of Populism

Populism in the Netherlands has increased, and evolved, over the last two decades—and it has received significant international attention. While right-wing politicians’ words influence debate, and their successes, such as they are, attract media attention, their parties have not been able to join governing coalitions. The extent of their support is also shifting: The significant showing of Baudet’s FvD in the March 2019 provincial elections was primarily at the expense of Wilder’s PVV. Baudet’s newer brand of right-wing rhetoric, and suggestions of solutions, not just problems, attracted some voters seeking change. First, his party had to find members to fill the seats won—a problem Wilders has also faced.

The rise of, and interest in, right-wing politicians means the profile of the Netherlands with regard to migration is no longer only about the facts of who is arriving, how long they are staying, or how well they are doing, but also about the way in which perception and the politics of immigration and integration has changed. This started with the flamboyant Pim Fortuyn in the early 2000s. Following his murder, and the posthumous electoral success but failure in power of his eponymous party (Lijst Pim Fortuyn), the mantle was taken up by Wilders. He has done more than anyone else to fuel the anti-immigration debate in the Netherlands and ignite anti-Islam sentiment across a vocal minority of the Dutch population. He has also gained international notoriety. Wilders worked his way through the VVD party into Parliament and has been more known for speaking for the man on the street. Under police protection and moving regularly in the face of constant threats, he is opposed to immigration, Islam, and any form of immigrant integration that alters a “pure” vision of Dutch culture. The personal is clearly not political in his case: Neither his Indonesian mother, nor his Hungarian wife, temper his outspoken public statements against Muslims, Eastern Europeans, and immigrants.

The newer man on the Dutch right-wing scene, Baudet, also has Indonesian ancestors, and comes from a family of cultural and intellectual figures. A self-styled eccentric intellectual who turned to politics in 2017 after his academic ambitions floundered, he has access to money, has a doctorate, and draws upon his youth, physical appearance, and penchant for self-promotional stunts to raise his profile. Baudet has railed against Dutch academia, media, and experts, stating that they are undermining and breaking “Boreal” Europe (a term used by right-wing European figures to indicate an Aryan, original continent). In addition, Baudet has, according to various accounts, sought out figures such as Jean-Marie Le Pen and daughter Marine, and has apparently been supported by similar Russian mechanisms as have disruptors elsewhere on both sides of the Atlantic.

Nonetheless, a crowded multiparty landscape and proportional representation system means that gaining 14 percent of the vote makes Baudet’s party, while the biggest, one that is unlikely ever to attract sufficient support from mainstream parties to be able to join, let alone lead, a governing coalition. A major question for the future of Dutch politics and policies on immigration and integration in particular is whether the mainstream can resist the electoral pull to the right, and reignite interest in the facts and realities on the ground. While centrist and left-leaning parties were relatively successful in the 2017 election, pulling in 36 percent of the vote between them, only D66 among them is in the coalition. The emphasis on immigration policy seemed to be clearly to the right. However, early analysis of Baudet’s 2019 successes suggests that the VVD and centrist parties may see openings on the left.

Stemming the Populist Tide?

In advance of the 2017 election, many commentators around the world thought Wilders’ party could win, particularly in the light of the populist victories of the Leave campaign in the Brexit referendum and of Donald Trump in the United States. However, the Dutch parliamentary system and the other parties’ pact not to work with the PVV made its rise into government all but impossible. Wilders and his followers can be expected to continue to play a vocal role in shaping Dutch, and European, political debates around migration, but the actual policy impact of those debates is open to question.

In the Netherlands, as elsewhere, little is “as usual” in politics at present. Quite how the pieces will settle remains unclear, but the rise of the PVV and arrival of the FvD and other anti-immigrant, anti-Islam voices suggests one possibility is more fragmentation and turmoil—in policy and public debates at least. On the other hand, the typical Dutch search for compromise could mean that the mainstream right-of-center parties start looking more to the left to bring balance.

The history of the Netherlands has long been marked by significant immigration and emigration, and both look set to continue. The culture of the country has long been one of openness and tolerance, with a vibrant cultural and sporting scene that encompasses many immigrant and refugee writers, comedians, thinkers, scholars, activists, and athletes. While there are global, regional, and national concerns about the impacts of migration and of religious extremism, supporting a seeming rise in Dutch intolerance to newcomers, the reality on the ground at the local level tends to show a different picture. Multiculturalism may be gone, and integration a heated topic. But it is not yet clear that right-wing rhetoric will transform the Netherlands into a closed society: In the end, actions speak louder than words.

Sources

Asylum Information Database (AIDA). 2018. Statistics, The Netherlands—Applications and Granting of Protections Status at First Instance, 2018. Updated February 18, 2019. Available online.

Barker, Memphis. 2018. Muhammad Cartoon Contest in Netherlands Sparks Pakistan Protests. The Guardian, August 29, 2018. Available online.

Central Statistical Office (CBS). 2016. Population Growth Fueled by Immigration. News release, January 28, 2016. Available online.

---. 2016. Wie zijn de derde generatie? News release, November 21, 2016. Available online.

---. 2017. Bevolking, huishoudens en bevolkingsontwikkeling; vanaf 1899. Statistics table. Updated December 29, 2017. Available online.

---. 2018. Bevolking; generatie, geslacht, leeftijd en migratieachtergrond, 1 januari. Statistics table. Updated May 14, 2018. Available online.

---. 2018. Aantal immigranten en Emigranten ook in 2018 hoog. News release, October 30, 2018. Available online.

---. 2018. Bevolking; kerncijfers. Statistics table. Updated October 30, 2018. Available online.

---. 2019. Meer asielzoekers in 2018, minder nareizigers. News release, February 11, 2019. Available online.

Dalen, Hendrik van and Kène Henkens. 2008. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty in the Netherlands. Vox (CEPR), October 6, 2008. Available online.

Ebus, Bram. 2018. Venezuelan Migrants Live in Shadows on Caribbean’s Sunshine Islands. The Guardian, November 13, 2018. Available online.

Eurostat. 2019. Acquisition of Citizenship per 1,000 Persons, EU-28 and EFTA, 2017. Updated March 2019. Available online.

Heilbron, Belia. 2017. Recordaantal buitenlandse studenten in Nederland. NRC, March 30, 2017. Available online.

Heyma, Arjan, Paul Bisschop and Cindy Biesenbeek. 2018. De economische waarde van arbeidsmigranten uit Midden- en Oost-Europa voor Nederland. SEO Economisch Onderzoek, June 2018. Available online.

Jessun d’Oliviera, H.U. 2018. Sta dubbele nationaliteit toe: hoogtijd vanwege de Brexit. De Volkskrant. August 15, 2018. Available online.

Kabinetsformatie. 2017. Vertrouwen in de toekomst: Regeerakkoord 2017-21 (Trust in the Future: Coalition Agreement 2017-21). Kabinetsformatie, October 10, 2017. Available online.

Kinderombudsman. 2017. Standpunt: een alternatief kinderpardon dat recht doet aan kinderen (Point of View: An Alternative Children’s Amnesty That Does Right by Children), June 29, 2017. Available online.

Migration Law Clinic. 2017. The “Bewijsnood” Policy of the Dutch Immigration Service: A Correct Interpretation of the Family Reunification Directive or an Unlawful Procedural Hurdle? Migration Law Clinic, May 2017. Available online.

Natter Katharina and Hein de Haas. 2018. There’s No Hard Right-Soft Left Divide on Migration Policy. Refugees Deeply, July 25, 2018. Available online.

Oudejans, Nanda and Tamar de Waal. 2017. Integratiebeleid Rutte III is in strijd met onze rechtsstaat (Integration Policy of Rutte III Is in Conflict with Our Constitutional State). NRC, October 10, 2017. Available online.

Papademetriou, Demetri and Natalia Banalescu-Bogdan. 2017. The Dutch Elections: How to Lose and Still Shape the Direction of a Country—and Possibly a Continent? Commentary, Migration Policy Institute, March 2017. Available online.

Petities.nl. 2018. Eens Nederlander, altijd Nederlander (Once Dutch, Always Dutch). Accessed April 27, 2018. Available online.

Pieters, Janene. 2018. Wilders Wants Dutch with Dual-Nationality to Lose Voting Right. NL Times. April 9, 2018. Available online.

Reimerink, Letty. 2015. In a City of Immigrants, Rotterdam’s Muslim Mayor Leads by Example. Citiscope, November 20, 2015. Available online.

Rijksoverheid. 2018. Kamerbrief over integrale migratieagenda, March 30, 2018. Available online.

Spaink, Karin. 2017. Rechts, Rechter, Rutte (Right, Righter, Rutte). Sargasso, October 10, 2017. Available online.

Timmermans, Frans. 2017. Turkije-deal werkt, nu ook nieuwe samenwerking zoeken met Afrika (Frans Timmermans: Turkey Deal Works, Now Also Seeking New Cooperation with Africa). De Volkskrant, June 15, 2017. Available online.

World Bank. 2017. Population Density (People per Sq. Km of Land Area). Accessed April 27, 2018. Available online.