You are here

U.S. Government Rush to Evacuate Afghan Allies and Allocate Sufficient Special Visas Comes at Eleventh Hour

An Afghan man speaks to an interpeter working with the U.S. Marine Corps. (Photo: U.S. Marine Corps)

Editor's Note: This article was revised on August 23, 2021 to correct the name of Operation Allies Refuge and the congressionally mandated timeline for processing SIV cases, which is nine months.

Confronting the withdrawal of its forces from Afghanistan by the end of August, the U.S. government at the eleventh hour is taking steps to address the fate of Afghans whose assistance during two decades of war has put their lives and those of their families at risk. President Joe Biden in July announced a plan dubbed Operation Allies Refuge to evacuate from the country the Afghans whose visa applications have been stuck in a years-long limbo. And the House, in a rare overwhelmingly bipartisan vote, on July 22 voted to increase the number of Special Immigrant Visas (SIV), a special category of visas created by Congress, to accommodate the arrivals. These actions came just weeks before the U.S. military ends operations in Afghanistan that began shortly after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks orchestrated by al Qaeda, which used the country as its base of operations.

Many Afghans who provided interpretation, security, cultural advice, intelligence, and other services to the U.S.-led military coalition have faced reprisal from Taliban insurgents. More than 300 Afghan interpreters or relatives have been killed because of their U.S. ties, according to the nonprofit organization No One Left Behind. New reports emerged last week of one interpreter being beheaded by the Taliban after they captured him at a checkpoint.

Efforts to bring these Afghans to the United States have been longstanding. For 15 years, the SIV has offered Afghans with a demonstrated record of assisting the U.S. government a path to U.S. permanent residence. Through June, nearly 77,000 Afghans had immigrated to the United States on these visas.

But since its creation, the SIV program has been hamstrung by processing delays and backlogs. An estimated 18,000 Afghan allies and 53,000 family members remained in the processing backlog earlier this year. The average application takes over two years to complete.

The first flights under Operation Allies Refuge, scheduled for the end of July, were due to bring about 2,500 Afghans who had already undergone security screenings to the Army’s Fort Lee in Virginia, for final processing. Another group of Afghans in earlier stages of the process are likely to be flown to other countries to finish their applications, before possibly being resettled in the United States. Qatar and Kuwait are reportedly likely to accept some Afghan nationals; Guam, Kazakhstan, the United Arab Emirates, and Uzbekistan are possible additional locations, although details had not been announced at this writing.

While there are logistical, legal, and security considerations to take into account in moving such large numbers of people so quickly, the United States has twice before undertaken significant evacuations of foreign citizens who provided assistance during overseas military conflicts. The first was the well-known evacuation of U.S. allies out of Vietnam during the fall of Saigon in 1975. The second, lesser known, was the airlift of Iraqi Kurds in 1996.

Creation of the Special Immigrant Visa

Afghan allies have been eligible for the SIV since 2006, receiving lawful permanent residence upon arrival, allowing them to obtain a green card. There are two SIV pathways for Afghan nationals, which mirror similar pathways for Iraqis.

Congress created the first SIV program in 2006. A permanent program, it allows entry annually for up to 50 Afghan or Iraqi interpreters or translators who worked with U.S. armed forces for at least one year. Their spouses and minor children can also receive visas, which are not counted under the cap. The visas available through this program annually were temporarily raised to 500 for fiscal years (FY) 2007 and 2008. To date, just 3 percent of Afghan allies have come through this pathway.

In 2008, Congress established a second, larger SIV for Iraqis who were employed in any role by or on behalf of the U.S. government for at least one year after March 2003. The application period for this program expired in September 2014, although some applications are still being processed.

In 2009, Congress created a similar program for Afghan nationals who supported U.S. government or allied forces since October 2001. Legislation initially mandated at least one year of service, later changed to require two years of service for those filing after September 2015. The initial cap under the program was set at 1,500 principal applicants per year, but was repeatedly increased and switched from being an annual limit to an overall ceiling. The latest cap allows for a total of 26,500 visas to be allotted to principal applicants filing after December 2014 and by December 31, 2022, when the program is set to expire. Of those 26,500 visas, slightly more than 15,600 had been issued as of April 2021.

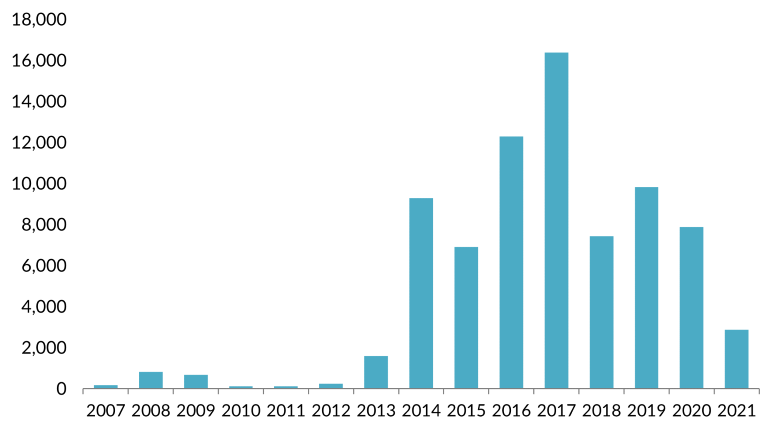

Figure 1. Special Immigrant Visas Issued to Afghans, FY 2007-21

Notes: Data combine counts for both SIV programs for Afghans. Numbers include both principal applicants and family members. Data for fiscal year (FY) 2021 include visas issued through June 30.

Source: Andorra Bruno, Iraqi and Afghan Special Immigrant Visa Programs (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2021), available online; U.S. Department of State, Refugee Processing Center, “Amerasian & SIV Arrivals by Nationality and State: October 1, 2020 through June 30, 2021,” updated July 6, 2021, available online.

SIV Application Process

To receive a visa under the larger SIV program, Afghans must complete a 14-step process that begins with applying to the U.S. embassy’s Chief of Mission (COM) in Afghanistan. The process has three main stages.

First, applicants must establish eligibility by demonstrating their record of service to the United States through a letter confirming employment, a letter of recommendation from their direct U.S.-citizen supervisor, and by detailing the threats received due to their employment by the U.S. government.

After COM approval, they must apply to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) for a visa. This application includes the COM approval letter and supervisor’s letter of recommendation.

If approved, their case is passed to the State Department. Applicants must submit biographical information about themselves and their spouses and children, and appear for an in-person interview at the embassy. After the interview, the U.S. government conducts background, security, and other checks, and, if they pass these, applicants must undergo a medical screening at their own expense. If applicants pass, they are issued an immigrant visa.

SIV recipients can receive assistance similar to that available to resettled refugees. This can include a loan for the cost of their flight and resettlement services such as financial assistance and help finding employment.

Program Delays and Backlogs

The Afghan SIV programs have suffered processing delays throughout their history, which have led some applicants to abandon the process and try their luck as asylum seekers in Europe or other parts of the world.

In 2013, Congress passed legislation requiring the State Department to complete processing of an SIV application within nine months. But the department has never been able to consistently meet that requirement. The average processing time currently is 703 days. But the actual time to receive a visa is even longer because this estimate does not include the time needed for steps within applicants’ control, such as filling out applications, providing supporting documentation, and obtaining the medical screening.

Of the roughly 18,000 principal applicants stuck in the SIV processing backlog, somewhere around half have submitted complete applications to the COM and are somewhere along the three-stage process; the other half have not yet submitted all required documents to the COM.

The State Department has identified two particular parts of the application process that cause delays. First, during the initial application to the COM, the government sometimes struggles to reach employers to verify applicants’ employment. Employment verification can be particularly difficult for Afghans who worked as contractors rather than as direct U.S. government employees. Second, following applicants’ interviews at the embassy, the government conducts extensive and often lengthy background and security checks. These checks are typically completed within 45 days but can take more than a year. Further, inadequate staffing, which has not been addressed over the past five years, has contributed to the growing backlog.

In 2018, a group of Afghan and Iraqi SIV applicants sued the government for failing to meet the mandated nine-month timeline for case completion. A federal judge in Washington, DC ruled in their favor in September 2019, and later applied the ruling to all SIV applicants whose applications are pending for more than nine months. In June 2020, the district court required the government to follow set timelines for each processing step and report on its progress meeting those timelines. As of July, the State Department met the standards for seven steps but failed to meet timelines for three others: adjudication of initial applications by the COM, in-person visa interview scheduling, and post-interview security checks and other processing.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further delayed approval of many applications. The U.S. embassy in Kabul, as U.S. embassies and consulates around the world, suspended visa interviews in March 2020 and restarted them only in February 2021. Since temporary consular staffing arrived in early 2021, the embassy has been able to clear the pandemic interview backlog. This is notable, given that the State Department has otherwise been unable to tackle the enormous backlog of more than 500,000 visa interviews that built up worldwide due to the coronavirus. However, the Kabul embassy was shuttered again from mid-June to early July by a major COVID-19 outbreak.

Attempts at Improvement

The Biden administration has taken preliminary steps to address some delays. In a February executive order, Biden directed the State Department to review the SIV program within 180 days, with emphasis on tackling processing and employment verification challenges. Beyond dispatching temporary staff to Kabul to speed the processing of SIV applications, the government assigned 50 additional staff to the State Department’s SIV processing team in Washington.

As of March 31, there were fewer than 11,000 visas still available for the estimated 18,000 applicants in the backlog. Secretary of State Antony Blinken asked Congress to authorize 8,000 additional visas—a call the House answered by passing the ALLIES Act on July 22, with wide bipartisan support.

However, it is not clear if those 8,000 additional visas will be sufficient. Even once the current backlog is cleared, the SIV program will accept applications through 2022 and the Kabul embassy aims to remain open for processing. As conditions in Afghanistan change following the U.S. troop withdrawal, former employees and contractors may feel increasingly unsafe. More applications may be forthcoming. The State Department has reportedly started an action group to identify Afghans who worked with the government but have not yet applied for the SIV.

Beyond providing new SIVs, the ALLIES Act would remove some of the more burdensome requirements of the application process. Given the widespread reports that Afghans who helped the U.S. government face reprisal from the Taliban, the bill would remove the requirement that applicants provide a “credible sworn statement” of the threats they face. And it would expand eligibility to those who worked with allied forces.

In June, the House passed a bill aimed at easing the medical exam for Afghan allies, which has represented another hurdle. Under current guidelines, SIV applicants must seek medical clearance from a single clinic in Kabul, which can be difficult and dangerous to reach from other parts of the country. The HOPE for Afghan SIVs Act would allow applicants to complete their medical screening within 30 days of U.S. arrival. Both the ALLIES Act and HOPE for Afghan SIVs Act are expected to have strong support in the Senate.

An emergency appropriations bill introduced in the Senate would accomplish a number of these measures at once. It includes provisions to increase the Afghan SIV cap by 20,000, reduce the employment requirement from two years to one, postpone applicants’ medical exam until after U.S. arrival, and provide SIV status for relatives of applicants who were killed. The bill has yet to receive a vote.

Pressing Considerations

Whatever the future for Afghan SIV applicants, many are likely to spend several months in processing. Given the pace of the Taliban’s advance, the Biden administration’s plan to evacuate large numbers of applicants and their families aims to provide a haven while applicants wait out this review. But any evacuation requires addressing a complicated set of humanitarian, logistical, legal, and security considerations.

One is how broad the evacuation program should be. The Biden administration seems focused on first helping those in the SIV backlog whose applications have advanced to some level of vetting. That leaves open the fate of those who might be eligible but have only just begun or not yet started their application. Human-rights advocates have pushed the administration to consider assisting Afghans who worked with the U.S. government but do not qualify for an SIV because of minor blemishes on their record or lack of a close tie to a U.S. supervisor who can write a recommendation. There have also been calls to extend protection through the SIV or other forms of immediate protection to other particularly vulnerable groups of Afghans, including journalists, humanitarian workers, activists, and vulnerable children.

On the logistical end, arranging transportation out of the country could be increasingly complicated as the U.S. presence in Afghanistan dwindles and the Taliban increases its territorial control. Transportation for Afghans outside of Kabul could be particularly difficult and dangerous. The International Refugee Assistance Project has recommended a combination of ground convoys with air cover and evacuation flights to reach eligible applicants across Afghanistan.

In terms of U.S. immigration law, relocating to the United States people who have not yet been approved for a visa would require the government to grant them humanitarian parole, which allows entry but does not open any direct path to permanent residence. Parole is allowed for "urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit,” and is supposed to be granted on a case-by-case basis, although it has been used broadly in the past.

In the current context, the government would likely try to parole in only applicants who have undergone some security checks and whom it expects will be successful in their SIV application. This is because a large and rushed parole program or other form of expedited vetting could bring greater concerns that unqualified applicants are given U.S. protection. Such challenges have befallen other humanitarian programs, including recently the Direct Access refugee program for Iraqis, which was created in 2008 to speed resettlement of those under threat for working with the U.S. government. Authorities are reportedly investigating impersonation fraud allegedly committed by 4,000 Iraqis who applied through the Direct Access program, including more than 500 who had already entered the United States (none are suspected of terrorist ties). The suspects are accused of stealing case files, including work and military service histories and accounts of persecution, of other Iraqis. These findings have reportedly complicated consideration of a similar accelerated refugee program for Afghan nationals.

Finally, anyone on U.S. soil—either in Guam or the U.S. mainland—whose application is denied based on perceived ineligibility or security grounds would have the right to appeal or could opt to file for asylum in the United States. Bringing Afghan nationals to a U.S. military base or location in another country, as the Biden administration seems poised to do, would foreclose most opportunities for appeals or asylum claims.

Prior History of U.S. Evacuations

These complications notwithstanding, the government has twice before evacuated foreign wartime allies. The first was as Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese in April 1975. The United States intended to evacuate Vietnamese allies who had assisted the U.S. government as well as those with U.S. relatives or other strong U.S. ties, and bring them to the United States under the president’s parole authority. Nearly 112,000 Vietnamese were evacuated to the U.S. territories of Guam and Wake Island, where troops had cleared land and constructed tent cities (some also passed through evacuation sites in the Philippines).

Upon arrival, U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) agents screened entrants for eligibility for parole and collected information for identification and security checks. Given evacuees’ limited documentation and the use of informal interpretation, the screenings were reportedly quite cursory and most people were deemed eligible for parole. Parolees were flown to military bases on the U.S. mainland where they underwent full security checks and medical screening. Voluntary agencies sought sponsors for each family’s resettlement into U.S. communities. Charitable organizations, faith groups, individual volunteers, and even state and municipal governments joined in the effort. Vietnamese with family in the United States or sufficient funds and a resettlement plan were released without sponsors. In 1977, Congress passed a law allowing Vietnamese, Cambodian, and Laotian nationals who had been paroled into the United States and who had been physically present for two years to get a green card.

In the much smaller Operation Pacific Haven in 1996, after Saddam Hussein’s forces made an incursion into Iraq’s Kurdish region, the United States airlifted to Guam more than 6,000 Iraqi Kurds who had been allied with U.S. forces. They were granted humanitarian parole to enter Guam and then expeditiously processed for asylum. All asylees were transported to the U.S. mainland within seven months.

Protection Impulses Slowed by Challenges

There is historical precedent for offering protection to Afghans who aided the U.S. government; recognizing the importance of critical in-country assistance, the United States has generally aimed to protect those who have assisted its armed forces in combat. But the Afghan response is taking place in a new context with unique challenges.

The perceived crisis at the U.S. Southwest border has left a long shadow on all immigration-related policy decisions. A second complication is the mandate for strict security screening given the presence of terrorists and groups that give them shelter in Afghanistan. The amount of time required for such careful and thorough screening is now at odds with the perilous moment Afghanistan is entering and the very real danger confronting those with U.S. ties.

Afghans who assisted the U.S. government have strong advocates. Human-rights groups have been calling loudly for more assistance, as have many U.S. veterans who worked closely with Afghans during the war. Perhaps most important among these is the growing cadre of veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan who are members of Congress. The call for assistance for Afghan allies has garnered a level of bipartisan support rare in most immigration policy debates.

There is reason to believe that Americans will support relocation efforts for Afghans who have proven their loyalty to the United States, particularly those who have already undergone extensive vetting. However, logistical constraints may play a large role in how many are able to take advantage of these efforts. And it is less clear whether human-rights advocates will succeed in their calls for protections for other vulnerable Afghans.

The SIV is not the only path available to Afghans in danger. Perhaps surprisingly, the United States has resettled a relatively limited number of Afghans through its refugee resettlement program over the past 20 years—an average of about 1,000 per year. Regardless of what happens to the SIV, those refugee numbers might change. Biden has promised to dramatically increase the resettlement ceiling up to 125,000 in FY 2022, which would be the highest level since 1993. Whether the government carries through and resettles greater numbers of Afghans in the years ahead will reveal the strength of its commitment to helping other Afghans at risk once the United States ends its two-decade military presence in the still-unstable country.

Sources

Afghan and Iraqi Allies Under Serious Threat Because of Their Faithful Service to the United States, on Their Own and on Behalf of Others Similarly Situated v. Antony Blinken et al. 2021. Case 1:18-cv-01388-TSC, Document 138 (United States District Court for the District of Columbia, Progress Report, July 2021). Available online.

Afghan and Iraqi Allies Under Serious Threat Because of Their Faithful Service to the United States, on Their Own and on Behalf of Others Similarly Situated v. Michael Pompeo et al. 2019. Case 1:18-cv-01388-TSC, Document 75 (United States District Court for the District of Columbia, September 2019). Available online.

---. 2020. Case 1:18-cv-01388-TSC, Document 88 (United States District Court for the District of Columbia, February 2020). Available online.

Allies Act of 2021. 2021. HR 3985, 17th Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 167, no. 106, daily ed. (June 17, 2021): H 2926-7. Available online.

An Act to Authorize the Creation of a Record of Admission for Permanent Residence in the Cases of Certain Refugees from Vietnam, Laos, or Cambodia, and to Amend the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act of 1975 to Extend the Period during which Refugee Assistance May Be Provided, and for Other Purposes. 1977. Public Law 95-145, U.S. Statutes at Large 1223 (1977): 1223-5. Available online.

Bruno, Andorra. 2021. Iraqi and Afghan Special Immigrant Visa Programs. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. Available online.

Coburn, Noah. 2021. The Costs of Working with the Americans in Afghanistan: The United States’ Broken Special Immigrant Visa Process. Providence, RI: Brown University, Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs. Available online.

Emergency Security Supplemental to Respond to January 6th Appropriations Act. 2021. S 2311, 17th Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 167, no. 121, daily ed. (July 12, 2021): S 4828. Available online.

HOPE for Afghan SIVs Act of 2021. 2021. HR 3385, 17th Cong., 1st sess., Congressional Record 167, no. 88, daily ed. (May 20, 2021): H 2648. Available online.

International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP). 2021. Recommendations for Immediate U.S. Government Actions to Protect Afghan Civilians. Statement, IRAP, New York, April 2021. Available online.

Kheel, Rebecca. 2021. US to Evacuate Afghans Who Assisted U.S. Military. The Hill, July 14, 2021. Available online.

Landay, Jonathan and Ted Hesson. 2021. U.S. Suspects 4,000 Cases of Fraud in Iraqi Refugee Program -Documents. Reuters, June 18, 2021. Available online.

Lubold, Gordon and Michael R. Gordon. 2021. Pentagon to House Afghan Interpreters at Military Bases in U.S., Qatar. Wall Street Journal, July 19, 2021. Available online.

National Immigration Forum. 2021. Fact Sheet: Evacuating our Allies from Afghanistan. Fact sheet, National Immigration Forum, Washington, DC, June 2021. Available online.

No One Left Behind. N.d. Home. Accessed July 20, 2021. Available online.

Reuters. 2021. Key Dates in U.S. Involvement in Afghanistan Since 9/11. Reuters, July 2, 2021. Available online.

Simon, Caroline. 2021. House Passes Bill to Authorize 8,000 More Visas for Afghan Allies. Roll Call, July 22, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of State. 2021. Joint Department of State/Department of Homeland Security Report: Status of the Afghan Special Immigrant Visa Program. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State. Available online.

U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs. N.d. Special Immigrant Visas for Afghans - Who Were Employed by/on Behalf of the U.S. Government. Accessed July 19, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of State, Office of Inspector General. 2020. Review of the Afghan Special Immigrant Visa Program. Arlington, VA: U.S. Department of State. Available online.

U.S. Department of State, Refugee Processing Center. 2021. Refugee Admissions Report as of June 30, 2021. Available online.

U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO). 1975. U.S. Provides Safe Haven for Indochinese Refugees. Washington, DC: GAO. Available online.

Wadhams, Nick and Eltaf Najafizada. 2021. Blinken Vows Visas for Afghans Who Worked with U.S. Troops. Bloomberg, June 7, 2021. Available online.

Wen, Anne. 2020. From War to Paradise: Kurdish Refugees Began New Lives in Operation Pacific Haven. Pacific Daily News, November 29, 2020. Available online.

White House. 2021. Executive Order 14013 of February 4, 2021: Rebuilding and Enhancing Programs to Resettle Refugees and Planning for the Impact of Climate Change on Migration. Federal Register vol. 86, no. 25 (February 9, 2021): 8839-44. Available online.

Williams, Abigail, Dan De Luce, and Courtney Kube. 2021. Biden Admin Now Plans to Evacuate 2,500 Afghans Directly to the U.S. NBC News, July 16, 2021. Available online.