You are here

Who Represents the Country? A Short History of Foreign-Born Athletes in the World Cup

Soccer players during a match. (Photo: iStock.com/FG Trade)

When the FIFA Men’s World Cup kicks off in Qatar on November 20, locals will have their eyes fixed firmly on one man: Almoez Ali. A striker, Ali was on the Qatar national squad that won the 2019 AFC Asian Cup, in which he scored a record nine goals and his team beat more established powerhouses such as Japan and South Korea.

Ali was not born in Qatar, however, but in Sudan. During the competition, he and a teammate overcame charges from the United Arab Emirates of playing for Qatar illegitimately, after having acquired citizenship through naturalization. He is not alone. In fact, about half of the Qatari men’s squad was born abroad. Ali’s mother was born in Qatar, making him eligible to play for the country, but teammates such as Portuguese-born center back Pedro Miguel seem to have no prior connections with the Gulf nation. Exact details of how they became Qatari nationals remain unclear; Qatar typically erects steep obstacles to citizenship acquisition, but seems to have created an easier path for players on the national soccer team.

Qatar may be an exceptional case in that such a large share of its team is foreign born, but in international athletics having players of different national origins is by no means unique. On average, nearly 10 percent of players in previous World Cups have competed for countries in which they were not born. In some cases, these players had always been able to obtain the national team’s citizenship, such as through their parents or grandparents, although in many cases they acquired the nationality later in life. In others, they were citizens from birth, even though born in another country.

Soccer, as the most popular sport on the planet, offers a prime example of the way that national belonging, citizenship, and migration play out on the athletic field. But similar questions regularly arise in other sports. At the recent Winter Olympic Games in Beijing, for instance, California-born skier Eileen Gu made history as youngest ever Olympic freestyle ski champion, a competition she won as a member of Team China, the country of her mother’s birth, after having previously represented the United States. In 2018, Bruno Massot and Aljona Savchenko won the Olympic gold for pairs figure skating on behalf of Germany, after having previously represented France and Ukraine, their respective countries of birth.

This year’s World Cup in Qatar will feature world-famous athletes at the top of their careers, competing for one of the most cherished trophies in all of sports. For many fans and viewers, the World Cup also offers an opportunity to examine complex questions about who countries select to represent the nation. When fans cheer on their national teams, who, really, are they supporting?

Drawing on research by the Sport and Nation research project of Erasmus University Rotterdam, this article examines the use of citizenship in international sporting competitions, particularly the FIFA World Cup.

Box 1. Calculating Soccer Players Born Abroad

Data in this article are derived from analysis conducted by the Sport and Nation project at Erasmus University Rotterdam. Of 10,137 soccer players to compete in a World Cup between 1930 and 2018, 996 were born in a country other than the one they represented on the field. This is almost 10 percent of the selected players per World Cup. Some players may have held citizenship of the team’s country since birth, and others acquired it later in life.The History of Internationally Born Competitors at the World Cups

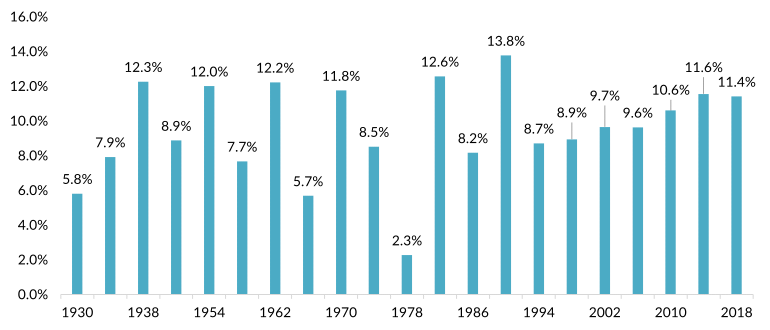

Players born in a country other than that of the national team for which they play have represented countries in the FIFA World Cup since it began in 1930 (see Figure 1). Historically, in fact, it has been quite common for players to represent countries other than the one in which they were born. Famous examples include Argentina-born Alfredo Di Stéfano, who played for Argentina and Spain from the 1940s to the 1960s, and Hungarian-born Ferenc Puskás, who represented Hungary and Spain around the same era. Perhaps most memorably, Argentina-born Luis Monti represented his country of birth in the 1930 World Cup and four years later represented Italy, the country where his parents were born. With both teams Monti reached the finals, making him the only man to play in multiple World Cup finals for different national teams (he lost with Argentina but won with Italy).

Figure 1. Share of Athletes at FIFA Men’s World Cups Representing a Country in Which They Were Not Born, 1930-2018

Notes: Data are based on international borders as of 2020 and include players born in a former colony or a country that no longer exists, such as Yugoslavia.

Source: Analysis of player rosters by the author, Gijs van Campenhout, and Jacco van Sterkenburgm.

In recent decades, players have represented national teams other than that of their country of birth on a consistent basis. In most cases, they compete for countries historically connected to their country of birth, such as former colonial powers, friendly states, or neighbors, all of which are likely to have a degree of cultural similarity and where they are likely to have acquired citizenship easily. This is true, for instance, with the current Qatari national team, where most players were born in North Africa or the Middle East, are native Arabic speakers, and Muslim, among other shared qualities.

Furthermore, over time players’ countries of birth have become more diverse, although there have been huge differences between countries. The United States, for instance, has historically selected the most players born abroad—48 as of 2018—whereas Brazil has as of this writing never once had on its national team an athlete born elsewhere. Given the immense talent pool in Brazil, a soccer-mad country that has won the World Cup more times than any other nation, the contrast with Qatar could not be starker.

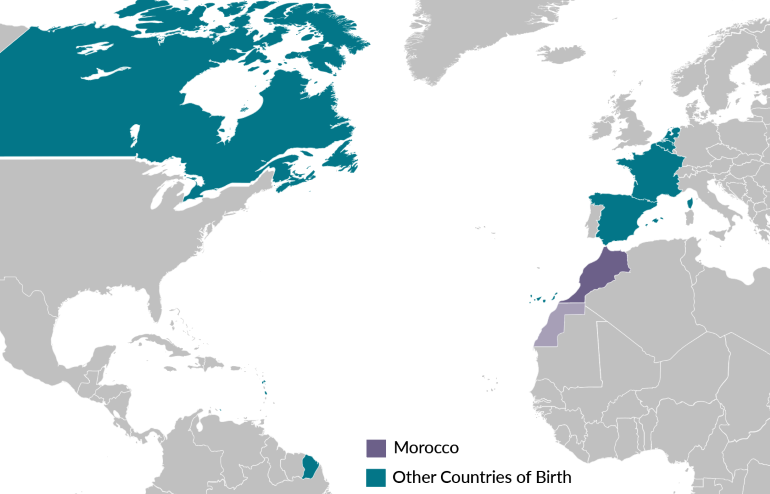

In Morocco, 17 of the 23 players brought to the 2018 FIFA World Cup were born outside the country (see Figure 2). Five were born in the Netherlands, prompting many Dutch fans—particularly those of Moroccan heritage—to follow the team with added interest. Eight other players were born in France, two in Spain, and one each in Belgium and Canada. The team’s composition involved a diversity of languages including Arabic, Dutch, French, and Spanish. Even though none of the players were born in England, English was used to communicate with those who did not speak Arabic.

Figure 2. Countries of Birth of Players on the Morocco Men’s National Soccer Team, 2018

Note: Map includes Western Sahara, a disputed territory, as a part of Morocco and is not intended to imply endorsement or acceptance of territorial boundaries.

Source: Author’s analysis.

Similarly, of the 22 players the Republic of Ireland brought to the World Cup in Italy in 1990, 16 were born in the United Kingdom.

Challenging the Makeup of “National” Teams

Questions about national teams strike at the heart of the conception of the nation. Nine members of France’s World Cup-winning squad in 1998 were either immigrants or the children of immigrants; when the French team won again two decades later, the squad carried 17 immigrants or children of immigrants, all but two of whom were of African descent. Steve Mandanda, for instance, was born in what was then Zaire, Benjamin Mendy has Senegalese parents, Paul Pogba’s are from Guinea, and Nabil Fekir’s family is Algerian. Once all the African nations’ teams had been eliminated, many fans turned to France’s lineup as the next best thing. And when les Bleus lifted the trophy, many soccer fans across Africa cheered the victory just as passionately as supporters in France.

In the United States, South Africa-born comedian Trevor Noah summed up the feelings of many: “Africa won the World Cup! Africa won the World Cup!” he claimed on The Daily Show, a popular late-night television program. “I get it—they have to say it’s the French team. But look at those guys, eh? You don’t get that tan from hanging out in the South of France, my friends.”

Not everyone was as willing to embrace the team’s multinational lineage. The French ambassador to the United States, Gérard Araud, strongly criticized Noah’s remarks. He declared that France did not consider its citizens in terms of race, religion, or migration background. “France is indeed a cosmopolitan country, but every citizen is part of the French identity and together they belong to the nation of France,” he wrote in a letter to Noah. “To us, there is no hyphenated identity, roots are an individual reality.” In the view of Araud and others, Noah denied the players their French identity by referring to their African roots, and also played into racist tropes that ignore the history of Black people in France. In his letter, the ambassador underlined that the rich and varied background of the French team reflected the country’s diversity. Which led Noah to reply: “I’m not trying to be an asshole, but I think it's more a reflection of France’s colonialism. Because it’s not like it’s just random—they all have something in common.”

How Do People Acquire Citizenship?

Outside the sports world, nationality is not subject to debate for many. Nationality is most typically achieved by place of birth (jus soli) or by descent, through parents or grandparents (jus sanguinis). The sociologist Rogers Brubaker has demonstrated how these different systems emerged as result of the civic and ethnic approaches to national membership formed in France and Germany in the 18th and 19th centuries. The French understanding of citizenship and nationhood was based on birthright and was inclusive: Everyone born on French territory was French or, in the case of parents with different nationalities, could become French. The French tended to define their country as a political unit; the major question was not what makes someone French, but instead who would enjoy political rights. Similarly, the development of U.S. citizenship was based on territorial birthright, although the children of U.S. nationals born abroad are also entitled to citizenship at birth. Informed by the country’s experience with millions of enslaved people, debates in the early 19th century established the terms under which immigrants could become U.S. citizens.

The German understanding, however, was based on descent, ethnocultural, and therefore exclusive. Blood, ancestry, and Volksgeist (sometimes translated as “national spirit”) created the nation. The Netherlands uses a similar system to grant citizenship: anyone born to at least one Dutch parent is entitled to Dutch citizenship at birth.

These two principles show how easy it might be for an individual to obtain multiple nationalities even from birth. For instance, a child born in the United States to a Dutch father and a German mother is entitled to citizenship from the United States, the Netherlands, and Germany.

Naturalization represents a third major way of acquiring a nationality, allowing migrants who have lived, worked, and paid taxes somewhere for several years—usually more than five, sometimes ten or more—to acquire nationality, sometimes after taking a citizenship test. This is the jus nexi principle, as defined by legal scholar Ayelet Shachar as based around an individual’s genuine connections to their new country. Long-term residence, marrying a citizen, and, in some cases, investing a significant amount of money in a country are also pathways to securing citizenship. This further compounds the complexity, making it easier for some people to have loyalties and legal status with multiple countries.

Sports and Nation

International sports competitions tend to be based around citizenship, with athletes mostly able to compete only on behalf of countries of their nationality. Yet often in these instances, rules for granting citizenship are conveniently stretched. For players, multiple nationalities allow them an opportunity to compete at the highest level and be a part of a team with the best opportunity for success. For countries, a broader pool provides the opportunity to select the best possible team and increase the chances of a victory.

The existence of players holding multiple nationalities and the incentives for national teams to recruit top players have led to a dizzying array of rules governing when and how an athlete can switch from representing one country to another. The Olympic Charter typically requires a three-year waiting period between the time an athlete switches teams and their appearance at the Olympic games. FIFA last updated its eligibility rules in 2020, allowing athletes with multiple nationalities to switch national teams only once, so long as they have not played in more than three matches for the previous team. The rules also allow players over age 18 who have lived in a country for multiple years (three years if they moved there under age 10; five years if they moved later) to play for its national team.

At times, the situation has led to high-stakes anxiety among sports fans tracking which of an athlete’s multiple citizenships they will represent on the field, a decision typically involving considerations of the team’s prospects, the player’s role, and myriad other questions aside from national allegiance. In an extreme case, midfielder Adnan Januzaj had five teams he could have chosen to play for ahead of the 2014 World Cup: Belgium, the country of his birth, or Albania, Kosovo, Serbia, or Turkey, all of which he was able to represent through his parents and grandparents (although Kosovo at the time was not recognized by FIFA).

What Does It Mean to Root for a National Team?

At the World Cup and other international sports competitions, many people around the world will sing their country’s national anthem, wave national flags, and dress in national colors. At times like this, sports may seem to have replaced the battlefields of the past. On the surface, for many people supporting one’s national team is natural or self-evident; supporting anyone else would feel disloyal.

And when players seem to turn on their country of birth, the reaction can be fierce. Striker Diego Costa’s 2013 decision to represent Spain rather than Brazil, the place he was born and for which he played in two friendlies, made him a subject of vitriol. Amid the outrage, the Brazilian soccer federation demanded he be stripped of his Brazilian citizenship.

Toward Future World Cups

One of the major questions raised by the Sport and Nation research is whether there is an increase in the number of internationally born players at the World Cup. From a historical perspective, the answer is no. The share of athletes playing for a country other than the one in which they were born has remained relatively stable between 2 percent and 14 percent since the first games in 1930. But there are some interesting differences. Countries such as England, France, and the Netherlands, which have long colonial histories, have often tapped their colonial talent pools to recruit players born abroad and the children of immigrants.

Going forward, soccer fans are likely to see an increasing number of teams built around players in the diaspora, similar to those of Morocco and Tunisia in recent years. Countries such as Taiwan, Vietnam, and some in sub-Saharan Africa will increasingly attract players born internationally who learned their skills in Europe but share a connection to the homeland.

Recently, former colonized countries including Curaçao and Suriname seem intent to capitalize on top-tier athletes who share an ancestral link, by allowing dual citizenship or introducing a so-called sports passport, as Suriname did in 2019 to sidestep its restrictions on multiple citizenship. A sports passport does not give voting rights, the right to own property, access health care, or other government services, but allows athletes to represent the country without giving up other nationalities. In Suriname’s case, the special passport allows it to attract players of Surinamese heritage from the Netherlands, its former colonial power, who would likely not be able to secure a position on the Dutch national team. Doing so could help Suriname, a country with a population of less than 1 million, improve its chances in regional and global competitions. After the sports passport was introduced, Suriname qualified for the regional CONCACAF championship competition for the first time since 1985.

FIFA has agreed to Suriname’s sport passport, but does not allow players to switch national teams after competing at the senior level. Fans and players might object, however. Allowing top-tier Dutch-Surinamese players such as Georginio Wijnaldum and Virgil van Dijk to play for Suriname at, for instance, the end of their careers would conceivably improve the quality of the national game and indeed raise the stakes for the regional competition.

What about Qatar? The country has been criticized for giving passports to talented players to increase its chances at the World Cup and other competitions. Other countries have been flexible with their citizenship regimes as well. Ecuador, for instance, was recently found to have used a false document in securing a passport for a Colombian-born player, prompting the team to be deducted three points in qualifying for the 2026 tournament. Qatar’s efforts are in line with the country’s broader focus on soccer-based diplomacy, which also includes hosting this year’s World Cup, its ownership of French titan Paris Saint-Germain, and partial ownership of Portuguese team SC Braga. But there is little reason to believe that other countries will follow suit. Notably, immigrants comprise more than 70 percent of Qatar’s population. In that sense, the national team reflects the makeup of the country, just as former colonial powers and the United States imagine themselves as countries of immigrants and feature athletes born all over. Whatever the case, if Ali scores at this year’s World Cup he will almost surely be cheered on both in Doha and Khartoum.

Sources

Africa Times. 2018. France’s World Cup Win Celebrated Across Africa. Africa Times, July 16, 2018. Available online.

Brubaker, Rogers. 1998. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Daily Show. 2018. Twitter post, July 16, 8:14 p.m. Available online.

---. 2018. Twitter post, July 18, 9:09 p.m. Available online.

French Embassy to the United States. 2018. Twitter post, July 18, 5:13 p.m. Available online.

Griffin, Thomas Ross. 2022. Homeland: National Identity Performance in the Qatar National Team. In Football in the Middle East: State, Society, and the Beautiful Game, ed. Abdullah Al-Arian. London: Hurst/Oxford University Press.

Kettner, James H. 1978. The Development of American Citizenship, 1608-1870. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

Manfred, Tony. 2014. Diego Costa, the Brazilian Striker Who's Playing for Spain, Is the Most Hated Man at the World Cup. Insider, June 12, 2014. Available online.

Oonk, Gijsbert. 2019. Who Are We Actually Cheering On? Sport, Migration, and National Identity in a World-Historical Perspective. Rotterdam: Erasmus University Rotterdam. Available online.

---. 2022. Sport and Nationality: Towards Thick and Thin Forms of Citizenship. National Identities 24 (3): 197-215. Available online.

Shachar, Ayelet. 2009. The Birthright Lottery: Citizenship and Global Inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Van Campenhout, Gijs, Jacco van Sterkenburgm, and Gijsbert Oonk. 2018. Who Counts as a Migrant Footballer? A Critical Reflection and Alternative Approach to Migrant Football Players on National Teams at the World Cup, 1930–2018. The International Journal of the History of Sport 35 (11): 1071-90. Available online.

---. 2019. Has the World Cup Become More Migratory? A Comparative History of Foreign-Born Players in National Football Teams, c. 1930-2018. Comparative Migration Studies 7 (22): 1-19. Available online.