You are here

Border Déjà Vu: Biden Confronts Similar Challenges as His Predecessors

Unaccompanied minors undergo processing at a temporary migrant facility in Texas. (Photo: Jaime Rodriguez Sr./U.S. Customs and Border Protection)

President Joe Biden’s administration is facing a burgeoning crisis as projected record-breaking numbers of foreign-born children arrive at the U.S. southern border seeking refuge. The challenge, which Biden says was to be expected, has been met with a lack of adequate resources, preparedness, and public relations. The backlash has been swift and is quickly affecting the administration’s ambitious immigration policy agenda, with potential ripple effects on other top domestic policy priorities.

The arrival of vulnerable populations, especially children and families from Central America, has been a daunting challenge for close to a decade, with pronounced peaks in 2014 and 2019. But the last three months have seen the fastest rate of increase in arrivals of unaccompanied children on record, with nearly 5,700 arriving in January, just under 9,300 in February, and possibly more than 17,000 in March. This pace of arrivals has created the perception of both an out-of-control border and a heart-wrenching humanitarian emergency.

What the current situation shares with the prior peaks is that, despite Biden’s promises for different responses, his administration has been consumed by meeting immediate needs on the ground. Those demands have cost precious time in launching the long-term reforms that treat the flows as an enduring phenomenon, given the pressures driving people to leave Central America. Instead, it appears the administration is repeating actions that treat the problem as short-lived. Its inability or unwillingness to acknowledge that reality has caught this administration unprepared, as were its predecessors.

The Current Burgeoning Crisis

The number of migrants arriving at the southern border is high, putting this year on pace for perhaps the highest number of “encounters”—a newly coined term including both apprehensions and expulsions by authorities—in the past 20 years. However, unlike prior periods, most encountered individuals are being quickly expelled from the country. This is because the Biden administration has largely kept in place a health-related order issued under Title 42 of the U.S. code by President Donald Trump, mandating the expulsion of unauthorized border arrivals. As a result, most single adults and many families—who comprise more than 90 percent of overall encounters—are quickly returned to Mexico or their home countries. However, the Biden administration has exempted unaccompanied children from the Title 42 order, triggering the current challenge. (The administration has also declined to immediately return some migrant families crossing illegally, potentially due to Mexican authorities’ unwillingness to accept them.)

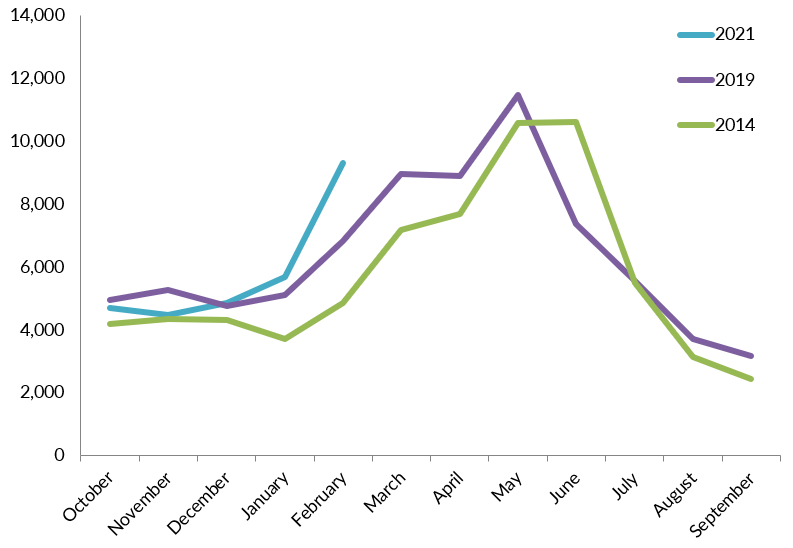

In February, nearly 9,300 unaccompanied minors were apprehended or expelled at the southwest border. This does not surpass prior surges in fiscal years (FYs) 2014 and 2019, which peaked at more than 10,600 in June 2014 and nearly 11,500 in May 2019. But the tally is higher than the numbers of children apprehended during February of those years: 4,800 and 6,800, respectively. According to reports, border officials are estimated to encounter more than 17,000 minors in March, an all-time high for any month. Thus, 2021 is on track to exceed prior interceptions of unaccompanied children.

Figure 1. Apprehensions and Encounters of Unaccompanied Child Migrants at the U.S. Southwest Border by Month, FYs 2014, 2019, and 2021

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “Southwest Land Border Encounters,” updated March 10, 2021, available online.

Under U.S. law, an unaccompanied child is someone who is not yet 18, unauthorized, and is unaccompanied by a parent or legal guardian. Unaccompanied children from noncontiguous countries, including Central America, are automatically permitted to enter the United States, while those from Mexico and Canada are only permitted to enter if U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) determines they are at risk of trafficking or persecution.

After apprehension, unaccompanied children are by law supposed to spend fewer than 72 hours in CBP custody before being transferred to the care of the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). This transfer is particularly important because CBP facilities are ill-equipped to hold children, especially for long periods of time.

However, because of limited capacity in ORR shelters, this transfer may be delayed beyond the legal limit, and many children have been stranded in CBP custody. At one point in March, more than 4,100 children were crowded into one tented CBP structure, according to media reports. This surpasses the nearly 3,000 children held in a single CBP shelter at one time in 2019. But it is difficult to compare these situations, since CBP capacity in 2019 was strained by other populations including single adults, some of whom ought to have been released more quickly using CBP’s discretion, a watchdog report later concluded. Today, CBP capacity challenges are largely due to children and some families.

The current rise in the number of unaccompanied child migrant arrivals dates back to August 2020, and accelerated after a court ordered the Trump administration in November to exempt unaccompanied children from the Title 42 expulsion order. Although the arrival of children predictably then rose, the Trump administration did not build the capacity to accommodate them.

Instead, as numbers increased, HHS had fewer than its standard number of available beds for children. In addition, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, available bed space for unaccompanied children had been reduced by 40 percent, leaving thousands of normally available beds offline, and bringing the numbers of available beds down from 13,500 in July 2020 to approximately 7,800 four months later. On March 5, the Biden administration urged shelters to lift these pandemic-related restrictions, but reopening licensed shelter bedspace is hard to do quickly. HHS has also sought to increase its temporary bed capacity by acquiring and building out new influx and emergency intake facilities.

Challenges with Placement

In addition to taking custody of unaccompanied minors, HHS is responsible for reuniting as many children as possible with U.S.-based relatives or close family friends. While it is important that these reunifications occur quickly, HHS is required to carefully vet potential sponsors to ensure the safety and wellbeing of the children.

This vetting process has become more difficult and cumbersome in recent years, as fewer sponsors have been parents, heightening the required reviews. Sixty percent of sponsors in 2014 were parents, but this number went down to 38 percent in 2020. Critics have pressed the need for greater vetting to prevent minors from being put in abusive situations, such as a case in 2014 when eight Guatemalan youths were released to sponsors who forced them to work 12-hour shifts at an Ohio egg farm and threatened them with death if they tried to escape.

The Trump administration increased the vetting and fingerprinting of potential sponsors and their household members, but also shared that information with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) for the purpose of immigration status checks. This led ICE to arrest 170 potential sponsors during a five-month period in 2018, 109 of whom had no criminal record. This had a clear chilling effect on sponsorships and the child population in HHS custody grew alarmingly. After it hit a high of almost 15,000 children in December 2018, the administration began to walk back some of its increased vetting measures. But the consequences of that experience seem to have lingered.

Why the Big Numbers Now?

The rising number of children arriving at the border is the result of numerous factors. In addition to the long-standing drivers of migration from Central America, the pandemic prompted a massive economic downturn, and Hurricanes Eta and Iota devastated parts of Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua in late 2020. A high number of children and families had also likely been waiting at the southern border after having been expelled from entering the United States since March 2020, when the Title 42 order went into effect. This year’s arrivals could thus possibly suggest a rebound or catch-up from an abnormally low year in 2020 as the pandemic sharply curbed human mobility of all types and led to strict public-health-related border closures.

President Biden is another new factor, and a narrative has persisted that his administration will be less restrictive than Trump’s. This narrative first developed during the Democratic Party’s presidential primaries, when multiple candidates aggressively sought to distinguish themselves from the Trump administration, especially at the border. Candidate Biden adopted that posture and, after entering office, his administration quickly unwound many of Trump’s restrictive southern border policies, including halting construction of the wall and ending the Migrant Protection Protocols (also known as the “Remain in Mexico” policy).

History of Prior Peaks: 2014 and 2019

The number of Central American unaccompanied children and families arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border has increased rapidly since 2011. In 2014 and 2019 the surge in arrivals overwhelmed U.S. facilities and adjudication capacity, and tested the political will of two presidential administrations.

Figure 2. Number of Family Units and Unaccompanied Children Apprehended or Encountered at the U.S. Southwest Border, FY 2012-21*

* Data for fiscal year (FY) 2021 go through February 2021.

Source: CBP, “Southwest Land Border Encounters,” updated March 10, 2021.

2014: Obama Responds to High Numbers but Fails to Make Enduring Structural Change

In 2014, a larger-than-expected number of unaccompanied children arrived at the southern border, mostly driven by violence, poor economic conditions, and the desire to reunite with family members in the United States. The numbers quickly overwhelmed U.S. capacity, leaving the children temporarily in makeshift facilities, with inadequate access to emergency services, and in years-long immigration court backlogs.

To address the surge, President Barack Obama’s administration launched a public-information campaign warning potential migrants about the dangers of the journey and countering smugglers’ claims that those who made it would be allowed to enter and remain in the United States.

The administration also placed unaccompanied children on an accelerated immigration court process called a “rocket docket.” However, this failed to actually speed processing of most cases, because the accelerated timeline only applied to the first of many hearings. Some court notices were also sent to the wrong address or never arrived. Out of concern for due process or recognizing that children were concurrently applying for immigration benefits before a different agency, many immigration judges granted extensions of or indefinitely delayed hearing dates. In the end, the promise of expedited court actions was never met.

In December 2014 the administration introduced in-country refugee processing for certain children in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. And after increased pressure from the United States, Mexico implemented the Programa Frontera Sur, significantly increasing immigration enforcement along its border with Guatemala and along popular migration routes within Mexico. As a result, while apprehensions at the U.S. border fell, arrests in Mexico rose significantly, suggesting that the levels of emigration from Central America remained fairly stable but more migrants were apprehended by Mexican authorities before reaching the United States.

The efforts successfully quelled the immediate crisis at the U.S. border, as the number of arrivals began to decline after their June 2014 peak. In the wake of 2014, the administration made changes to enact a more robust and flexible bed capacity framework as well as increase collaboration across relevant government agencies through a Unified Coordination Group. These changes allowed the government to respond with greater ease when unaccompanied child numbers rose again in 2016.

In order to further improve capacity and accommodate higher-than expected caseloads, beginning in 2015 the Obama administration annually asked Congress to provide ORR with a contingency fund. Congress has denied that—and has denied similar requests every year since. This pattern continued even under the Trump administration, which in FY 2021 requested a contingency fund capped at $2 billion over three years, but was again denied.

Despite the improvements made to receiving and housing unaccompanied children, they failed to adequately address the factors driving this enduring migration flow.

2019: Trump Takes Punitive Approach and a Cue from Obama

After the Trump administration’s rapid succession of increasingly punitive measures to deter migrants—most notably family separation—the number of arrivals increased to levels unseen in years. Already influenced by longstanding push-and-pull factors, thousands of unaccompanied children and other migrants rushed to get to the border before the next restrictive policy came down. The administration’s large-scale separation of families in the summer of 2018 also added to the pressure on government systems in 2019, as forcibly separated children were designated as unaccompanied and sent to ORR facilities. HHS, meanwhile, struggled as releases of children slowed amid the Trump administration’s increased vetting and immigration enforcement targeting potential sponsors.

To address these impediments, the administration eventually eased the new vetting requirements for sponsors and Congress forced the administration to stop sharing sponsors’ information for immigration enforcement purposes. The administration also followed its predecessor’s attempt at an accelerated court docket, but limited it to families at ten major immigration courts. It furthermore walled off the asylum system at the U.S. border, but the processing of unaccompanied children was largely unaffected by these changes.

Finally, after Trump threatened to impose steep tariffs, Mexico signed an agreement committing to deploy its National Guard to stop migrants, act to dismantle smuggling and trafficking organizations, and allow more asylum seekers to remain in Mexico under MPP. Within weeks, irregular migration at the U.S.-Mexico border and throughout Mexico sharply decreased.

Biden Administration’s Policy Responses

Given a similar, albeit not identical, challenge as his two predecessors, Biden and his administration have adopted some of the same strategies.

Like the Obama administration, Biden’s team has launched a public relations campaign in Brazil, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, using social media, television, and radio to spread the message that the border is closed. However, this message has been muddled by the administration’s unwinding of MPP and other restrictive policies, which may have spurred hope or signaled that the border was opening, despite the continuing expulsions.

Many of the administration’s efforts have focused on managing immediate capacity challenges. On March 13, it announced that the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) would help “receive, shelter, and transfer” unaccompanied children over the next 90 days. To increase the number of sponsors willing to come forward, the Department of Homeland Security formally terminated its 2018 information-sharing agreement with HHS over sponsors’ immigration status. ORR has also taken steps to streamline the release of children whose sponsors are parents or legal guardians.

The administration is in the process of creating joint processing centers so that children can be placed in HHS care immediately after the Border Patrol encounters them. While this is promising, there are concerns about clarifying whether HHS or CBP—a law enforcement agency—has the principal responsibility of caring for the children.

Biden is also re-booting the Obama-era Central American Minors (CAM) program, which allowed Central American children with a parent already lawfully in the United States to be screened for refugee status, and in some cases parole, from their country of origin or a neighboring country. The revival of CAM will take place in two parts: first, applications closed during the Trump administration will be reopened; then new applications will be accepted, although the parameters have not yet been announced.

The Biden administration has indicated it will start similar in-country processing programs for other groups, such as relatives with approved but backlogged green-card petitions. Such programs can be beneficial, especially if admissions criteria are generous and the application process is efficient—two areas where the original CAM program struggled. However robust or successful these programs may be, vulnerable populations and mixed flows of economic and humanitarian migrants will continue to travel to the U.S. southern border, thus requiring an ongoing effective infrastructure and adjudicatory capacity.

Like its predecessors, the Biden administration has sought Mexico’s help, asking it to accept more families expelled under the Title 42 order and increase enforcement in order to slow the pace of migrants reaching the U.S.-Mexico border. Mexico recently closed its border with Guatemala to nonessential travel and increased its military presence there. Biden appointed Vice President Kamala Harris to lead efforts to stem migration across the border, and recently sent border coordinator Roberta Jacobson and other officials to Mexico and Guatemala to seek their cooperation.

Finally, the Biden administration has indicated it will soon release a regulation to significantly shorten the time for asylum processing. But it has yet to indicate whether it will follow past examples and accelerate the processing of immigration court dockets.

The Need for Long-Term Reforms

A decade since increased arrivals of vulnerable populations from Central America began, it is clear that the country faces an ongoing challenge and must treat it as such.

ORR would benefit from a contingency fund to be able to quickly increase capacity on short notice. Each time ORR bed capacity has failed to keep up with rising numbers of unaccompanied minors, children have ended up waiting in crowded, unhealthy, and in some cases dangerous facilities. HHS must be able to scale up capacity when needed.

The government should also explore options to make the sponsor reunification process more efficient without compromising critical protections for children. The faster the reunification, the shorter that children stay in CBP custody and later ORR care. And if it is essential to hold minors in CBP facilities immediately upon their arrival, such facilities should be appropriately staffed and resourced. Expanding on the Biden administration’s plan to co-locate HHS personnel at CBP facilities, the government could ideally staff border reception centers with multiple agencies, so relevant professionals could appropriately care for and efficiently process vulnerable populations.

Most importantly, the U.S. government needs an efficient, timely, and fair mechanism to provide protection for genuinely vulnerable asylum seekers while restricting the admission of unauthorized immigrants without valid humanitarian claims. Children arriving today will be placed at the end of an immigration court backlog of more than 1.3 million cases and are unlikely to have their claims heard for years. That not only delays granting asylum to those deserving it, but also incentivizes the arrival of those who do not. Moving arriving asylum seekers’ cases off the immigration courts’ overburdened docket and establishing a new system that would allow U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) asylum officers to evaluate the full merits of the case would be a start.

With the understanding that they will not yield immediate results, the administration should also continue to pursue in-country changes, including development focused on economic insecurity, corruption, and other drivers of migration; expanded legal—especially labor—pathways to immigrate; and, eventually, a regional protection architecture that allows safe resettlement closer to migrants’ places of origin.

Broader Effects of the Border Challenges

The situation at the southern border will ultimately abate as more asylum seekers are processed and Mexico steps up enforcement. But it may have a lasting effect on the president’s agenda on immigration and beyond.

For one, it has rendered the administration’s goal of legalizing the country’s estimated 11 million unauthorized immigrants a nonstarter, even to some supporters. Focusing on narrower populations, the House of Representatives on March 18 passed two bills that would provide a path to legalization for DREAMers, who were brought to the country illegally as children, and agricultural workers. But the measures’ chances of passage in the Senate have dimmed. Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), cosponsor of the bipartisan DREAM Act, said he opposed “legalizing one person until you’re in control of the border.” For moderate congressional Republicans who might support modest immigration measures, the border challenge has provided a convenient way out or made the political price of support too costly.

In order to gain the critical support in Congress for long-needed reforms, Biden has to succeed where both Obama and Trump failed: achieve a sense of control at the border, recognized both domestically and abroad, and implement lasting and credible reforms that allow for humane, fair, and efficient processing of protection claims. This will encourage only those asylum seekers who meet the requirement for protection and deter those who do not. If these twin goals are not met, challenges at the border are sure to undermine the odds for sweeping changes in immigration law, just as they did for previous presidents.

Sources

Alvarez, Priscilla. 2021. More than 4,000 Unaccompanied Migrant Children in Border Patrol Custody. CNN, March 15, 2021. Available online.

Capps, Randy, Doris Meissner, Ariel G. Ruiz Soto, Jessica Bolter and Sarah Pierce. 2019. From Control to Crisis: Changing Trends and Policies Reshaping U.S.-Mexico Border Enforcement. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Faye Hipsman. 2016. Increased Central American Migration to the United States May Prove an Enduring Phenomenon. Migration Information Source, February 18, 2016. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Jessica Bolter. 2020. Interlocking Set of Trump Administration Policies at the U.S.-Mexico Border Bars Virtually All from Asylum. Migration Information Source, February 27, 2020. Available online.

Everett, Burgess. 2021. ‘God, No’: GOP Immigration Allies Disappear as Crisis Mounts. Politico, March 19, 2021. Available online.

Greenberg, Mark. 2021. Hampered by the Pandemic: Unaccompanied Child Arrivals Increase as Earlier Preparedness Shortfalls Limit the Response. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

Hesson, Ted. 2021. U.S. Moves to Speed Up Releases of Unaccompanied Migrant Children. Reuters, February 25, 2021. Available online.

Hesson, Ted and Aram Roston. 2021. Biden Administration Enlists FEMA to Help with Surge of Children at U.S.-Mexico Border. Reuters, March 13, 2021. Available online.

Jordan, Miriam. 2021. ‘No Place for a Child’: Inside the Tent Camp Housing Thousands of Migrant Children. The New York Times, March 30, 2021. Available online.

Kopan, Tal. 2018. ICE Arrested Undocumented Adults Who Sought to Take In Immigrant Children. The San Francisco Chronicle, December 10, 2018. Available online.

Meissner, Doris. 2020. Rethinking the U.S.-Mexico Border Immigration Enforcement System: A Policy Road Map. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

Meissner, Doris and Sarah Pierce. 2021. Biden Administration Is Making Quick Progress on Asylum, but a Long, Complicated Road Lies Ahead. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

Miroff, Nick, Karen DeYoung, and Kevin Sieff. 2021. Biden Will Send Mexico Surplus Vaccine, as U.S. Seeks Help on Immigration Enforcement. The Washington Post, March 18, 2021. Available online.

Montoya-Galvez, Camilo. 2021. Refugee Agency to Fast-Track Release of Some Migrant Children with Parents in the U.S. CBS News, March 23, 2021. Available online.

Morin, Rebecca. 2021. White House Says Migrant Situation 'Not a Crisis' as Biden's Border Czar Roberta Jacobson Heads to Mexico. USA Today, March 22, 2021. Available online.

P.J.E.S. v. Chad F. Wolf. 2020. U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, Order Granting Plaintiff’s Motion for a Preliminary Injunction. November 18, 2020. Available online.

Reuters. 2021. Mexico Rolls Out Steps to Tighten Southern Border with Guatemala. Reuters, March 19, 2021. Available online.

Rosenblum, Marc. 2015. Unaccompanied Child Migration to the United States: The Tension between Protection and Prevention. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

Soto, Ariel G. Ruiz. 2020. One Year after the U.S.-Mexico Agreement: Reshaping Mexico’s Migration Policies. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). 2021. Southwest Land Border Encounters. Updated March 10, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). 2021. Latest UC Data – FY2020. Updated February 1, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Administration for Children and Families. 2020. Justification of Estimates for Appropriations Committees. Washington, DC: HHS. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security. 2021. Homeland Security Secretary Mayorkas Directs FEMA to Support Response for Unaccompanied Children. News release, March 13, 2021. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Inspector General. 2021. DHS’ Fragmented Approach to Immigration Enforcement and Poor Planning Resulted in Extended Migrant Detention during the 2019 Surge. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

U.S. Department of State. 2019. U.S.-Mexico Joint Declaration. Media note, June 7, 2019. Available online.

U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR). 2015. Annual Report to Congress FY 2014. Washington, DC: ORR. Available online.

White House. 2021. Remarks by President Biden in Press Conference. March 25, 2021. Available online.