You are here

Ecuador: From Mass Emigration to Return Migration?

An event in Quito for día del Migrante (Photo: Carlos Pozo/Cancillería del Ecuador).

Ecuador’s geographical variety is nearly matched by its diverse migration patterns. Although it is a small Andean country of approximately 15.7 million people, Ecuador accounts for the largest Latin American nationality in Spain, the second largest in Italy, and one of the largest immigrant groups in metro New York. Ecuador also is an important migrant destination. The long-standing conflict in Colombia has driven tens of thousands of its citizens into Ecuador, making it the country in Latin America with the largest refugee population.

Since the early 1980s, Ecuador has experienced two major waves of emigration, sending 10 percent to 15 percent of Ecuadorians overseas. Today, an estimated 1.5 million to 2 million Ecuadorians live abroad. The first wave of migrants originated in southern Ecuador and departed in the early 1980s, heading mainly to the United States. The second wave left in the late 1990s and early 2000s and mostly went to Spain, the United States, and Italy. Since the mid-2000s emigration has slowed considerably, and the earlier waves have been replaced by a steady flow of Ecuadorians leaving to reunite with relatives abroad, most notably in Spain and, to a lesser extent, the United States and Italy.

Rafael Correa is the first president of Ecuador to reach out to Ecuadorians overseas. Since taking office in 2007, his administration has developed programs to encourage diaspora members to return. This state-led transnationalism coincided with the 2008 global economic crisis and Spain’s efforts to encourage unemployed immigrants to return to their home countries. Although efforts to pull and push Ecuadorians to return initially had minimal success, return migration from Spain has increased recently—a pattern likely to continue in the short term.

As Ecuador experienced the mass emigration of the early 2000s, it also received significant inflows, mostly from its immediate neighbors, Peru and Colombia. Most Peruvians are economic migrants, while the majority of Colombians are refugees, many of whom await a government decision on asylum. Other recent immigrants include a relatively small number of “amenity/lifestyle” migrants, many of whom are retirees, from the United States, Canada, and Europe.

This country profile offers an overview of the historical and more recent migration patterns to and from Ecuador, examining policies in the country and beyond that affect migration, the role of remittances, and a focus on Ecuadorians in key destination countries.

Historical Background

The population of what is now Ecuador witnessed considerable disruption between 1470 and 1540. The Inca invaded from Peru during the latter half of the 15th century, and Spanish conquerors arrived in 1534. As a result of the introduction of disease, abuse, and enslavement, more than 70 percent of the indigenous population died by the end of the century.

Few Spaniards or other Europeans immigrated to Ecuador during the colonial era, which lasted until 1822. The arrival of a few English men, some Spanish traders, and a handful of other Europeans was the exception.

In the mid-16th century, at least two slave ships from Panama bound for Peru wrecked on the shores of what is now Esmeraldas Province. The African slaves established a maroon society (freed slaves), and maintained autonomy during much of the colonial era.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, colonial authorities in Quito arranged for the shipment of African slaves, who were put to work in Ibarra, Guayaquil, and the gold mines of modern-day Colombia (Popayán). A smaller number of slaves were imported to Quito, Cuenca, and other urban areas. The colonial district of Quito, which extended into southern Colombia, had approximately 12,000 slaves, with an unknown population of descendants of slaves in Esmeraldas.

With the exception of Spaniards who became traders, Ecuador received very few of the Europeans who migrated to Latin America during the 19th and early 20th centuries. An 1890 census of Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest city, recorded fewer than 5,000 immigrants, more than half of whom were from Peru.

During Ecuador’s cocoa (chocolate) export boom of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, “Lebanese” began to immigrate to Guayaquil and quickly became merchants and traders. The term applies broadly to Arab-speaking, predominantly Christian, immigrants whose ancestry can be traced to Syria, Palestine, or Lebanon.

It is unknown how many “Lebanese” migrated to Ecuador, but the economic and political influence of their descendants has been much greater than their numbers. Two presidents in the 1990s were of Arab-origin descent, even as the community represented approximately 1,500 of the more than 1.2 million residents of Quito in 1991. Also, some of the most successful business families in Ecuador are “Lebanese.”

Ecuadorian emigration prior to the 1960s was minimal. A small number of people migrated to Venezuela and by the 1940s to the United States. Between 1930 and 1959, 11,025 Ecuadorians received lawful permanent resident status in the United States, according to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). By the 1960s, small communities of Ecuadorians could be found in Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York.

Emigration Since the 1960s: Economic Crises and Two Waves of Emigration

The provinces of Azuay and Cañar, and Ecuador’s third-largest city, Cuenca, formed the core migrant-sending zone in Ecuador in the 1970s and 1980s. The main sending communities practiced subsistence agriculture and had a tradition of women weaving Panama hats for export to New York, as well as male seasonal migration to the coast.

When the Panama hat trade declined in the 1950s and 1960s, pioneer migrants, mainly young and male, used this trade connection to migrate to New York, most of them without authorization. Most worked in restaurants as busboys or dishwashers, and a smaller number worked in factories or construction.

Migration remained slow but persistent during the 1970s; migrants from numerous communities in Azuay and Cañar provinces joined the clandestine migration networks that led people through Central America and Mexico en route to the United States. A small number migrated to Venezuela, whose oil-led economy was strong through the 1970s. As oil prices fell in the 1980s, Ecuadorian migration to Venezuela appears to have diminished.

Like many countries in Latin America, Ecuador in the 1970s experienced economic growth and improved living conditions. But in the early 1980s, oil prices collapsed, causing a debt crisis, an increase in inflation, and a dramatic decrease in wages. The crisis, Ecuador’s first since 1960, was particularly onerous on subsistence farmers, thousands of whom opted to emigrate. Economic reforms only worsened conditions, driving more people to emigrate.

Most of these migrants paid intermediaries—coyotes or document forgers—for clandestine passage to the United States, overwhelmingly to metro New York, but also to Chicago, Los Angeles, Miami, and Minneapolis. A 1986 U.S. immigration law that legalized nearly 3 million unauthorized immigrants resulted in lawful permanent resident status for 16,292 Ecuadorians, many of whom have since sponsored the legal emigration of family members.

Ecuador experienced another economic crisis in the late 1990s, the result of low oil prices and floods that damaged export crops, coupled with political instability and financial mismanagement. The national currency, the sucre, lost more than two-thirds of its value, and the unemployment rate rose to 15 percent and the poverty rate to 56 percent.

|

Spanish Policy and Ecuadorian Migrants

|

|

|

The crisis was directly responsible for a second wave of emigration, which sent between 500,000 and 1 million Ecuadorians overseas from 1998 to 2006, to the United States and Italy, but mostly to Spain, where few Ecuadorians lived prior to the crisis. This migrant flow was much more geographically and socioeconomically diverse. Emigrants came from every province, and were more urban and better educated; they also came from various ethnicities, including members of the Saraguro and Otavalo indigenous groups. Ecuadorians were able to migrate in such large numbers so quickly because of an existing agreement allowing Ecuadorians to enter Spain as tourists without visas (the law changed in 2003, see sidebar). Indeed, most of the first migrants in Spain were women who posed as tourists, some with the help of Ecuadorian travel agencies.

For its part, Spain offered plentiful, low-skilled work in the informal economy, and migrants did not have to worry about language differences. Most women worked as domestics while men found employment in the construction, agriculture, and service industries. By 2003, as many as 200,000 Ecuadorians resided in Spain, and for a few years Ecuadorians were the largest national immigrant group there. Ecuadorians also went to several other western European countries, most notably Italy.

Tightened borders in Central America and greater surveillance at the U.S.-Mexico border made clandestine migration to the United States more expensive and dangerous than migration to Spain, yet immigration from southern Ecuador, and to a lesser extent elsewhere, to the United States continued. Thousands of Ecuadorians traveled to Mexico or Guatemala on their way to the United States aboard fishing trawlers or other boats. Between 1999 and 2006 about 8,000 Ecuadorians were detained by the U.S. Coast Guard. Travel via this dangerous maritime route has largely ended; since 2009 the Coast Guard has detained fewer than 20 Ecuadorians.

Ecuadorians Abroad: Contemporary Trends in the Main Destination Countries

|

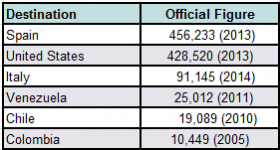

Table 1. Number of Ecuadorians Overseas in Favored Destinations

|

|

Sources: United States: U.S. Census Bureau, 2011-13 American Community Survey; Spain: Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, Municipality Survey; Italy: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica; Venezuela: Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, 2011 Census; Chile and Colombia: International Organization for Migration, Panorama Migratorio de América del Sur, 2012. |

Since the wave of the early 2000s, Ecuadorian emigration has slowed considerably, especially to Spain. Most migration to Spain effectively halted with the 2003 visa requirement, with the important exception of family unification. The global recession starting in 2008 and Spain’s deep economic problems also discouraged further emigration. The two waves of emigration and family unification have resulted in a large number of Ecuadorians living overseas. Slightly fewer than 1 million reside in the United States, Spain, and Italy (see Table 1). When all other countries are included, it is likely that between 1.5 million and 2 million Ecuadorians (legal and irregular) live overseas.

Ecuadorians in the United States

The number of Ecuadorians in the United States has held constant for nearly a decade, at an estimated 428,500 in 2013. Similarly, the geography of Ecuadorians has held constant with nearly 58 percent in the New York-New Jersey metro area, 6.5 percent in Miami, and 3.8 percent in Chicago. Ecuadorians are the third-largest Latin American immigrant group in the New York-New Jersey metro area, behind Mexicans and Dominicans, and the ninth largest nationally. As Ecuadorians have immigrated since the 1960s and have had many children in the United States, it is not surprising that the number of people who identify as Ecuadorian (approximately 665,000 in 2013) is 55 percent higher than the number of Ecuadorian immigrants.

Of the roughly 10,700 Ecuadorians granted legal permanent residency status in the United States annually between 2000 and 2013, more than 80 percent gained it through the “family sponsored preference” or “immediate relatives of U.S. citizens” categories of admission. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) estimated that 170,000 unauthorized Ecuadorians were in the United States in 2012.

Despite the high cost and danger, Ecuadorians still are attempting to enter the United States along the U.S.-Mexico border. The number of Ecuadorians apprehended increased from 3,298 in fiscal year (FY) 2011 to 5,680 in FY 2013. Deportations (removals and returns) of Ecuadorians have fluctuated between 2,000 and 3,000 since 2008.

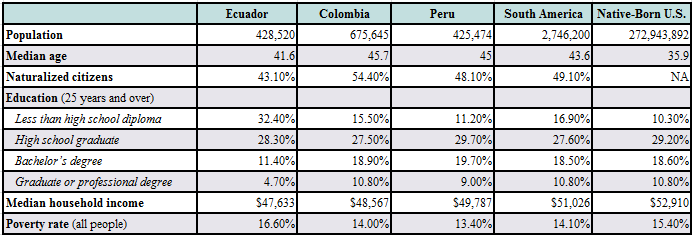

There is little social research on Ecuadorians in the United States. The 2013 American Community Survey (ACS), however, provides some important indicators on the socioeconomic status of Ecuadorian immigrants (see Table 2.) Their educational attainment is considerably less than the native-born population and that of Colombian and Peruvian immigrants. Ecuadorians' median household income is similar to that of their fellow Andean immigrants, although slightly lower than the overall South American immigrant average. Their poverty rate is higher than the South American average, and slightly higher than native-born households.

|

Table 2. Socioeconomic Indicators of Various South American Immigrant Groups in the United States, 2013

|

|

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2011-13. |

Ecuadorians in Spain

The 2005 Spanish regularization law granted legal status to nearly 200,000 Ecuadorians (see sidebar). The law implemented a municipal registry system, or padrón, through which it is believed that most immigrants, including unauthorized immigrants, have registered because it grants access to the national health system and to schools. Ecuadorians are categorized as foreign nationals, or, if they have been granted Spanish citizenship, as Spanish nationals.

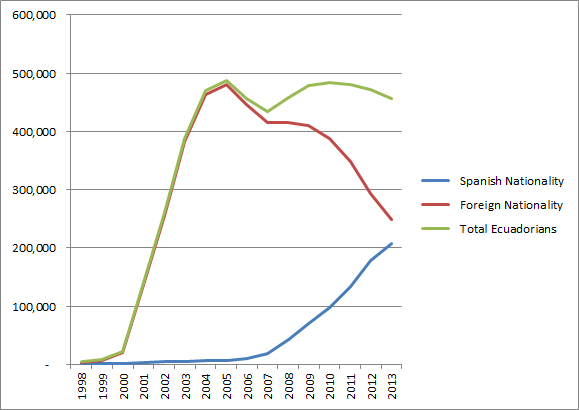

Although the number, location, and gender of the registered Ecuadorian population have deviated little since 2004 (see Figure 1), other characteristics have changed significantly. The Ecuadorian population hit a peak of 487,239 in 2005 before declining to 456,233 in 2013. About one-third lives in or near Madrid, and approximately 20 percent in Barcelona and Valencia/Murcia. Women account for about 52 percent of Ecuadorian migrants, down from more than 55 percent during the first wave of migration to Spain.

|

Figure 1. Ecuadorians in Spain by Nationality, 1998-2013

|

|

Source: Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Spain. |

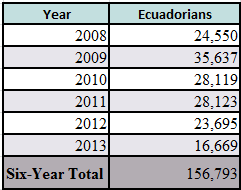

The most important changes for Ecuadorians in Spain have been the increase in the number of Ecuadorians with Spanish nationality, a shift in immigration pathways to family unification, and most recently an uptick in return migration. The number of Ecuadorians taking Spanish citizenship grew rapidly after the implementation of the 2005 regularization law. From 2006 to 2013 more Ecuadorians acquired Spanish nationality (232,645) than any other immigrant group; most under a law allowing Latin American immigrants to naturalize after two years of continuous legal residence in Spain. Many Ecuadorians who benefitted from the 2005 regularization were subsequently able to gain Spanish citizenship. Between 2008 and 2013 Spain’s family unification policy allowed nearly 157,000 Ecuadorians to join family members in the country, facilitating legal residence and thus Spanish nationality (see Table 3).

|

Table 3. Ecuadorians Granted Spanish Temporary Residency through Family Unification, 2008-13

|

|

Source: Ministerio de Seguridad Social, Spain. Anuario de Estadísticas. |

Pichincha (Quito) and Guayas (Guayaquil) were the two most common origin provinces for Ecuadorians to Spain and the average age of migrants was 27 for males, 26 for females, according to a 2007 Spanish labor force survey. Ecuadorians were less well educated than most other Latin American immigrant groups in Spain and appear to be only moderately better educated than Ecuadorians in the United States. Twenty-nine percent had primary education or less and 60 percent some secondary education. This is reflected in labor force participation. More than 85 percent of Ecuadorians were employed; men primarily in construction, agriculture, and industry, while women were concentrated in domestic service, hotel work, and commerce.

Since 2007, conditions for Ecuadorians in Spain have deteriorated drastically. The prolonged economic crisis has led to very high unemployment and a variety of other financial difficulties.

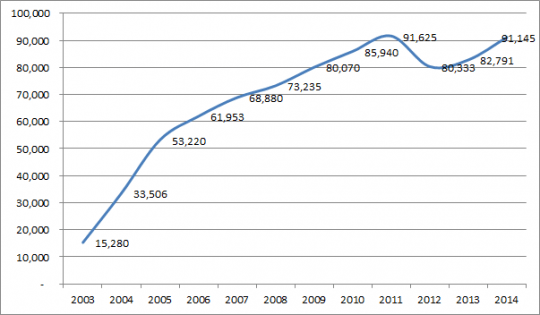

Ecuadorians in Italy

Ecuadorians remain an important immigrant group in Italy. With a population of 91,145 in 2014 they constitute the second largest Latin American immigrant group behind Peruvians, and the 13th-largest national group overall. Since 2004 the number of Ecuadorians has increased 50 percent, and a lopsided sex ratio persists; nearly 59 percent of Ecuadorian migrants are women, most working as care providers or in other domestic services. Ecuadorians are heavily concentrated in Liguria (Genoa) and Lombardia (Milan).

|

Figure 2. Number of Ecuadorians in Italy, 2003-14

|

|

Source: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica (Italy). |

The vast majority of Ecuadorians have legal residence due to Italy’s numerous and generous regularization programs. In 2002, for example, the Bossi-Fini legislation enabled the regularization of 634,000 irregular immigrants, including 41,571 Ecuadorians. In 2013, 2,136 Ecuadorians were legally admitted to Italy; 1,449 joined family members and 402 had work permits.

Remittances and Return Migration

The presence of a large number of Ecuadorians overseas is important for the Ecuadorian state and families in a number of ways, including economic, political, and with regards to human-capital enrichment. Transnational practices include forms of political engagement, such as permitting Ecuadorians abroad to vote in Ecuadorian presidential elections (allowed since 2006), and the sending of remittances. A significant stream of remittances has flowed to Ecuador, the result of family commitments and plans for an anticipated return. One of the most important migration-related developments since the mid-2000s has been the increase in return migration, especially from Spain.

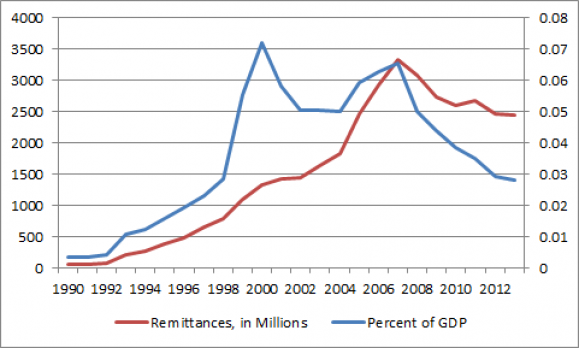

Remittances

Remittances are an important part of Ecuador’s economy and for many households (see Figure 3). The amount of remittances increased quickly in the early 2000s, peaking at $3.3 billion in 2007 before plummeting during the global economic downturn in 2008. Remittances from Spain fell from about $1.2 billion in 2007 to $944 million in 2010. The importance of remittances to the Ecuadorian economy, measured as percent of gross domestic product (GDP), has fluctuated based on the strength of the Ecuadorian economy; total remittances have held steady at about $2.5 billion since 2010, but as oil revenues have increased, the relative contribution to the overall economy has declined to about 3 percent. About half of annual remittances come from the United States and 43 percent from Spain. Remittances remain the second largest source of foreign reserves.

|

Figure 3. Remittances as Share of Ecuadorian GDP, 1990 to 2013

|

|

Source: World Bank Prospects Group, Annual Remittances Data, October 2014 update. |

Seven percent (266,313) of households in Ecuador received remittances at least once during 2010, the 2010 Ecuadorian Census found. Not surprisingly, the long-term core migrant-sending region, Cañar and Azuay provinces, had the highest percentages of recipient households, at 24.2 percent and 15.3 percent respectively; the biggest population centers, Guayas and Pichincha provinces, had the largest number of recipient households, at 72,160 and 55,376 respectively.

The 2007 Spanish labor force survey found that 68 percent of adult Ecuadorians in Spain sent remittances. Both men and women sent just over 2,000 euros per year, mostly to parents (60 percent) and children (20 percent). Based on a 2005 Ecuadorian government survey, researchers have found that the late 1990s wave of migration reduced poverty among households with a migrant abroad by about 20 percent, and that recipient households received about $1,600 in remittances annually. Data from the 2006 Living Standard Measurement Survey of Ecuador shows that nearly 44 percent of remittances received in the previous year were spent on food, 18 percent on education, 8.3 percent on eliminating debt, and 7.6 percent on health.

Return Migration

Ecuadorian return migration from Spain gained public attention as part of the exodus of immigrants and, to a lesser extent, natives from Spain in 2012-13. Spain recorded 396,658 fewer foreign nationals in 2014 than the previous year. Of that total, 56,466 were Ecuadorian, including those who had acquired Spanish nationality.

There are other indications that return migration to Ecuador has increased in the past few years. The 2010 Ecuador census found 63,888 people who had lived overseas in 2005; nearly half in Spain and about one-quarter in the United States. The Secretaría Nacional del Migrante (SENAMI, National Migrant Secretariat) estimated in early 2013 that it had assisted in the return of more than 40,000 Ecuadorians since 2008, with a larger return expected in 2013.

Spain’s prolonged economic downturn has been the main cause of return migration. In addition, some Ecuadorians have been deported from Spain or the United States, while others have chosen to leave the United States because of an inability to achieve legal status and increased difficulties for unauthorized immigrants. In addition, the Ecuadorian government has sought to encourage return migration, while the Spanish government has created incentives for migrants to leave Spain.

In 2007, Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa’s administration began a broad-based campaign to reach out to Ecuadorians overseas, or the “fifth region” as the diaspora was called, playing upon Ecuador’s four traditional geographical regions. The program Plan Bienvenid@ A Casa: Por un regreso voluntario, digno y sostenible (Welcome Home: for a voluntary, dignified and sustainable return) was implemented by SENAMI and encouraged return migration for families by helping with their transition. Return migrants can repatriate their belongings duty-free and qualify for employment assistance and start-up funds for certain productive investments via Plan Cucayo. It is unclear if these efforts have enticed Ecuadorians who were not already planning to return, but the initiative marks a significant departure from previous administrations in focusing on the diaspora.

Meanwhile, in 2009 the Spanish government implemented several programs to encourage emigration of both authorized and irregular immigrants. The Programa de Abono Anticipado de Presentación a Extranjeros (APRE) was designed to encourage legal immigrants to return to their home country by offering them free transportation and their unemployment benefits in a lump sum. Nearly 45 percent of APRE returnees were Ecuadorian. A second program, Plan de Retorno Social, encouraged irregular migrants, refugees, and others to return in exchange for airfare to their home country and some financial assistance during the transition. From 2009 to 2013, 6,406 Ecuadorians were among the 23,970 immigrants who took advantage of these two programs, which generated far fewer departures than Spain desired.

The future of return migration will depend on the strength of both the Spanish economy and Ecuadorians’ prospects for a productive return and (re)integration into the Ecuadorian economy and society. With Ecuador’s stable economic growth and low unemployment, and Spain’s persistently high joblessness, it seems likely that in the short term return migration from Spain will continue. Return migration from the United States of lawful permanent residents has never been large, but without the passage of significant immigration reform, more unauthorized Ecuadorians may choose to return.

Contemporary Immigration

The 2010 Ecuadorian census recorded 181,848 foreign born, just less than 1.3 percent of Ecuador’s then population of 14.3 million. While the immigrant share of the population is small, it represents a significant increase from 2001, when the foreign-born population stood at 104,130. The increase is attributable mostly to an influx of Colombians, whose numbers surged more than 38,000 since 2001 to 89,931 in 2010, and a 164 percent increase in the number of Peruvians, from 5,682 in 2001 to 15,016 in 2010. Combined, Colombian (49.5 percent), U.S. (8.6 percent), and Peruvian (8.3 percent) immigrant populations accounted for two-thirds of all foreign born in Ecuador in 2010. The actual number of Peruvians and Colombians is unknown because the borders are porous, many Colombian refugees avoid official counts, and the dangers of the Colombia-Ecuador border region make data collection difficult.

Ecuador’s decision in 2000 to switch its currency from the sucre to the U.S. dollar, known as dollarization, attracted many Peruvian migrants. Cuenca, situated in the middle of the original core migrant-sending zone to the United States, is the most popular provincial destination for Peruvians as U.S.-bound migration has tightened the labor market and increased wages. Since 2006, Ecuador has struck bilateral agreements with Peru on migrant regularization resulting in Ecuador periodically legalizing unauthorized Peruvians.

Armed conflict among the Colombian military, paramilitaries, and the rebel group FARC (Colombian Revolutionary Armed Forces) has been an important push factor for Colombians. The breakdown in peace talks in 2002 prompted a surge in refugees, and even though the Colombian government and the FARC have been in peace negotiations since 2012, government and FARC military operations continue.

This violence, coupled with herbicide spraying programs to eradicate coca crops in southern Colombia (via the United States’ Plan Colombia), have displaced tens of thousands, leading to the largest refugee population in Latin America. Nearly 147,000 Colombians lived in Ecuador as refugees or in refugee-like situations in 2014, according to United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates. Ecuadorian estimates are lower, with the government recognizing only 55,840 people as refugees in 2013. In addition to the border region, many Colombians live in Quito and Guayaquil.

The Ecuadorian government has struggled to address the refugee crisis. Since 2000 nearly 60,000 Colombians have received refugee status in Ecuador, more than 34,000 from 2009 to 2010 alone. The dramatic increase in 2009-10 resulted from the Correa administration’s “Enhanced Registration Process,” which saw teams of government workers seek out Colombians and quickly determine their asylum applications. The program was short-lived and in 2012 Ecuador implemented a new policy (Presidential Decree 1182) that was more restrictive. Of the 16,952 asylum applications received by Ecuador in 2012, only 1,543 were accepted—a rate of 9.1 percent, which was considerably lower than the previous average acceptance rate of nearly 25 percent. In 2014, almost 15,000 cases were pending, and hundreds of new asylum applications are submitted each month.

Other nationalities have migrated to Ecuador for economic opportunity and retirement amenities. More than 15,000 Americans were counted in the 2010 census, split nearly evenly among Ecuador’s largest urban areas, Guayas (Guayaquil), Pichincha (Quito), and Azuay (Cuenca). Cuenca has attracted the most attention as a retirement destination for a small (3,272) but growing number of Americans. As seen elsewhere in Latin America, particularly in Costa Rica and Panama, even small numbers of relatively affluent foreigners can have a significant economic and cultural effect.

A moderate number of Chinese and a smaller number of other Asians have immigrated to Ecuador recently. The 2010 census recorded 2,906 Chinese, more than double the 1,200 in the 2001 census. Despite their small numbers, the presence of Chinese immigrants is visible in the Chinese discount clothing stores that have appeared in nearly every Ecuadorian city.

Contemporary Migration Issues Facing Ecuador

Ecuador faces several migration-related challenges. First, the Colombian refugee situation remains a difficult humanitarian issue, and the flow of unauthorized immigrants will likely continue in the near future. Ecuador has retreated from its 2009 Enhanced Registration Policy, and has made gaining refugee status more difficult. Mistrust of and even open hostility towards Colombians persists. Second, Ecuador may receive a significant number of return migrants from Spain if high unemployment there continues. The Correa administration’s state-led transnationalism may have been designed more to continue the flow of remittances than to actually encourage permanent return migration. If a large number of migrants do return to Ecuador, they will need to find employment and reintegrate into Ecuadorian society. Return migrants may bring with them capital, business experience, and a desire to innovate and create social change, but the economic and political environment contexts are critical. Ecuador’s low unemployment and government spending may help the transition, but challenges remain. Many return migrants to southern Ecuador re-migrated to the United States after their economic enterprises failed or when they could not earn what they were accustomed to in the United States. The children of migrants raised abroad also face serious cultural adjustment issues upon return to Ecuador. Ecuador also continues to combat sex trafficking and other forms of exploitation. Although the U.S. Department of State reported in 2014 that most Ecuadorian trafficking victims are women and children within the country, Ecuador is also the destination of exploited women and girls from Colombia, Paraguay, and Peru, and the source region for a small number of Ecuadorian women who are sex trafficked to Colombia and Brazil.

The most recent wave of emigration was instigated by an economic and political crisis; the first wave in the 1980s was as well, but had been developing for more than 20 years when the debt crisis occurred. Ecuador does not face an imminent economic or political crisis, but the country’s economy relies heavily on oil export and government spending. If those two pillars were to collapse then a large number of Ecuadorians may look overseas again, most likely to where a significant number of their family, friends, and compatriots reside: Spain and the United States. Until that time, (should it happen at all) Ecuador will likely be addressing the complexities associated with a large refugee population, return migration, and regional increases in lifestyle migrants.

The author is grateful for the assistance of Seaira Christian-Daniels on this article.

Sources

Ayala Mora, Enrique. 2005. Resumen de Historia Del Ecuador. Quito, Ecuador: Corporación Editora Nacional.

Baker, Bryan and Nancy Rytina. 2013. Estimates of the Unauthorized Immigrant Population Residing in the United States: January 2012. Washington, DC: Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics. Available Online.

Bernardi, Fabrizio, Luis Garrido, and Maria Miyar. 2010. The Recent Fast Upsurge of Immigrants in Spain and Their Employment Patterns and Occupational Attainment. International Migration 49 (1): 148-87.

Bertoli, Simone and Francesca Marchetta. 2014. Migration, remittances, and poverty in Ecuador. Auvergne, France: Centre d'Etudes et de Recherches sur le Développement International. Available Online.

Boccagni, Paolo. 2011. The framing of return from above and below in Ecuadorian migration: a project, a myth, or a political device? Global Networks 11 (4): 461-80.

———. 2011. Reminiscences, patriotism, participation: approaching external voting in Ecuadorian immigration to Italy. International Migration 49 (3): 76-98.

Boccagni, Paolo and Francesca Lagomarsino. 2011. Migration and the Global Crisis: New Prospects for Return? The Case of Ecuadorians in Europe. Bulletin of Latin American Research 30 (3): 282-97.

Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. 2014. 2011 Census. Caracas: Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. Available Online.

Brey, Elisa and Mikolaj Stanek. 2013. Analysis of Existing Quantitative Data on Family Migration: Spain. Oxford, UK: IMPACIM. Available Online.

Bryant, Sherwin. 2006. Finding Gold, Forming Slavery: The Creation of a Classic Slave Society, Popayán, 1600-1700. The Americas 63 (1): 81-112.

Carrasco Carpio and Carlos García Serrano. 2011. Inmigración y mercado de trabjo. Informe 2011. Madrid: Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social. Available Online.

Chile, Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. 2002 Census. Santiago: Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. Available Online.

Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Immigration Statistics. 2014. 2013 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Washington, DC: DHS Office of Immigration Statistics. Available Online.

Ecuador, Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censo. 2001, 2010 Census (Censo de Población y Vivienda). Quito: Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censo. Available Online.

Feinstein International Center. 2012. Refugee Livelihoods in Urban Areas: Identifying Program Opportunities. Case study Ecuador. Sommerville, MA: Feinstein International Center. Available Online.

Finotelli, Claudia and Joaquín Arango. 2011. Regularisation of unauthorized immigrants in Italy and Spain: determinants and effects. Documents d’Analisi Geografica 57 (3): 495-515.

Hayes, Matthew. 2014. It is hard being the different one all the time: gringos and racialized identity in lifestyle migration to Ecuador. Ethnic and Racial Studies, August 12, 2014. Available Online.

Herrera, Gioconda, Maria Cristina Carillo, and Alicia Torres. 2005. La migración ecuatoriana: transnacionalismo, redes, e identidades. Quito, Ecuador: FLACSO-Plan Migración, Comunicación y Desarrollo.

Herrera, Gioconda, Maria Isabel, and Alexandra Escobar. 2012. Perfil Migratorio del Ecuador 2011. Ecuador: International Organization for Migration. Available Online.

Hiemstra, Nancy. 2013. Geopolitical Reverberations of US Migrant Detention and Deportation: The View from Ecuador. Geopolitics 17 (2): 293-311.

Guglielmelli White, Ana. 2011. In the shoes of refugees: providing protection and solutions for displaced Colombians in Ecuador. Research paper 217, UNHCR Policy Development and Evaluation Service, Washington, DC. Available Online.

Istituto Nazionale di Statistica Italy. 2014. Resident Population Data. Available Online.

Jokisch, Brad and David Kyle. 2005. Las transformaciones de la migración transnacional del Ecuador, 1993-2003. In La migración ecuatoriana: transnacionalismo, redes, e identidades, eds. Gioconda Herrera, Maria Cristina Carillo, and Alicia Torres. Quito, Ecuador: FLACSO-Plan Migración, Comunicación y Desarrollo.

Jokisch, Brad and Jason Pribilsky. 2002. Economic Crisis and the New Emigration from Ecuador. International Migration 40 (4): 75-102.

Kyle, David. 2001. Transnational Peasants: Migration, Networks and Ethnicity in Andean Ecuador. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lane, Kris. 2002. Quito 1599: City and Colony in Transition. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Levinson, Amanda. 2005. The Regularisation of Unauthorized Migrants: Literature Survey and Country Case Studies, Regularisation programmes in Italy. Oxford, UK: COMPAS. Available Online.

Margheritis, Ana. 2011. Todos Somos Migrantes (We are all migrants): The Paradoxes of Innovative State-led Transnationalism in Ecuador. International Political Sociology 5: 198-217.

Morales, Laura and Katia Pilati. 2014. The political transnationalism of Ecuadorians in Barcelona, Madrid and Milan: the role of individual resources, organizational engagement and the political context. Global Networks 14 (1): 80-102.

Newson, Linda A. 1995. Life and Death in Early Colonial Ecuador. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

Organización Internacional para las Migraciones (OIM). 2012. Panorama Migratorio de América del Sur. Buenos Aires, Argentina: OIM. Available Online.

Roberts, Lois J. 2000. The Lebanese Immigrants in Ecuador. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Simanski, John F. 2014. Immigration Enforcement Actions: 2013. Washington, DC: DHS Office of Immigration Statistics. Available Online.

Spain, Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. 2014. Labor Force Survey (EPA). Available Online.

———. 2014. Preview of the Continuous Municipal Register Statistics at 1 January, 2014. Press release, April 22, 2014. Available Online.

———. 2014. Municipality Survey (Padrón). Available Online.

Spain, Ministerio de Seguridad Social. 2014 Anuario de Estadísticas Spain. Various years. Available Online.

United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). 2008. Ecuador: Las cifras de la migración nacional. Quito, Ecuador: UNFPA and FLACSO. Available Online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2014. 2014 UNHCR country operations profile-Ecuador. Accessed October 10, 2014. Available Online.

———. 2014. Statistical Yearbook, Various Years. Geneva: UNHCR. Available Online.

U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey, various years. American FactFinder. Available Online.

U.S. Coast Guard. Alien Migrant Interdiction. Last updated October 20, 2014. Available Online.

U.S. Department of State. 2014. Trafficking in Persons Report 2014: Ecuador. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of State. Available Online.

World Bank Prospects Group. 2014. Annual Remittances Data, April 2014 update. Available Online.