You are here

Global Civil Society in Qatar and the Gulf Cooperation Council: Emerging Dilemmas and Opportunities

Migrant construction workers in the GCC (Photo: ILO Asia-Pacific)

In the contemporary world, international civil-society organizations have increasingly secured fundamental labor and human rights for vulnerable temporary labor migrants, while reinforcing governments’ legal and moral obligations to uphold international labor standards. The World Bank defines civil-society actors as a “range of non-governmental and non-profit organizations that serve the public and bear the burden of expressing their interests and values, based on ethical considerations, cultural, political, scientific, religious, and charitable factors.”

Recently, civil-society actors have campaigned to highlight labor violations by local and multinational corporations against temporary labor migrants in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). The GCC region, comprised of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), is the world’s largest recipient of temporary migrants, who constitute 43 percent of the total GCC population—and 86 percent of Qatar’s population.

While civil-society groups have been particularly focused on Qatar, highlighting the rising death toll among migrant workers racing to build massive construction projects in preparation for the 2022 World Cup, their interest also has extended more broadly across the GCC region. Among the criticisms: that the GCC governments are failing to uphold international labor standards, including the right to bargain or unionize, and that they are not effectively tackling other labor-rights violations, such as dangerous working conditions, overcrowded accommodations, and nonpayment of wages. GCC officials, in turn, are criticizing civil society for turning a blind eye to the internal security and demographic challenges their countries face, as well as ongoing policy efforts to address migrant workers’ issues.

International civil-society actors, including Amnesty International, the Building and Wood Workers International, Human Rights Watch, and the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC, a global umbrella of trade unions) have launched major campaigns to ensure temporary migrants’ rights and protections in Qatar and the broader GCC region.

Drawing from ethnographic observations and field interviews, this article examines the emerging complex roles, challenges, and opportunities of civil-society groups with regards to Qatar and the GCC region. It analyzes the prevailing legal and political structures where civil society operates and identifies potential common ground to mitigate labor- and human-rights violations under the GCC’s Kafala Sponsorship System.

Contextualizing Civil Society in the GCC: Typologies and Structures

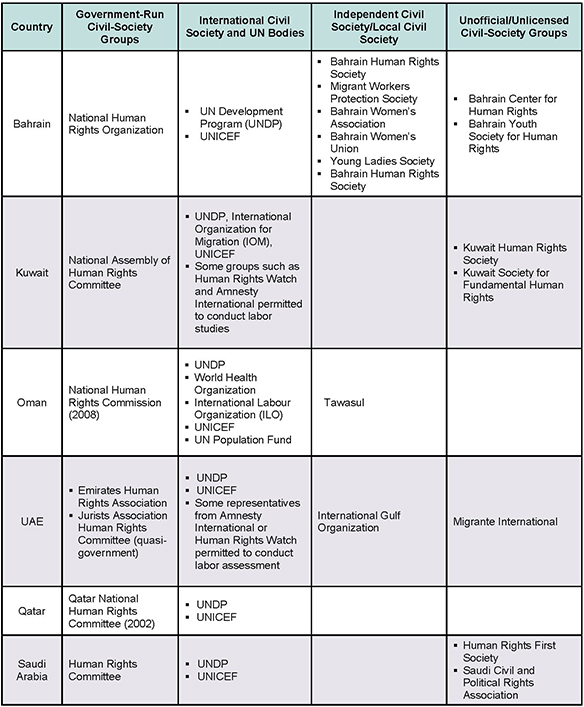

Over the past few years, various civil-society actors—particularly from the West—have increasingly pressured GCC governments to resolve migrant labor issues. While there are no official statistics, available evidence suggests that approximately 10,000 associations, private enterprises, and other civil-society groups are currently active within the region. To examine the complexity of these civil-society actors, four different groups have been identified: (1) government-run civil-society organizations, (2) local/transnational, migrant-run civil-society groups, (3) international civil-society actors, and (4) unofficial/unlicensed civil-society groups.

|

Table 1: Examples of Civil-Society Groups in the GCC

|

|

Source: U.S. Department of State, 2012 Human Rights Reports for Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, Washington, DC: Department of State, 2013, www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/2012/. |

Government-run civil-society groups’ interests mainly focus on GCC-specific issues such as welfare, marriage, and disability; in some cases, they provide charity-based financial and social assistance to migrant workers. Unlicensed civil-society groups such as in Kuwait (see Table 1) also partially focus on migrants’ issues, yet heavily address Kuwaiti nationals’ concerns. Local/transnational migrant-run and international civil-society groups mainly prioritize migrant labor concerns, particularly in issues of labor protections, monitoring, and legal rights. These clear diverging (and in some cases converging) interests often shape the operations and activities of civil-society groups in the GCC countries; in some cases, these groups develop collaborative efforts to improve migrants’ welfare and labor conditions.

Government-Run Civil-Society Groups

Government-run civil-society groups are locally based institutions primarily controlled and funded by the national government. They provide social and welfare services to their citizens and in some cases to select migrant populations, particularly humanitarian assistance.

Established in 2002, the Qatari National Human Rights Committee, for example, aims to uphold and promote human-rights principles mandated by the United Nations for all subjects within Qatar (including citizens, expatriates, and transit travelers). The Qatari government also has established charity-based organizations such as Reach Out to Asia to provide education, community welfare, and research throughout Asia. Similarly in Oman, the government formed the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) of the Sultanate of Oman by royal decree to promote human rights, freedom of expression, and equal opportunity principles.

Local and Transnational, Migrant-Run Civil-Society Groups

Local and transnational civil-society groups are mainly formed and managed by temporary labor migrants within respective GCC countries. In particular, the locally based groups are informally managed by temporary migrants, and are registered with their respective embassies. These local groups often focus on social and humanitarian initiatives for temporary labor migrants. In the United Arab Emirates, a vibrant Dubai-based Migrant Rights Council promotes legal, economic, and educational assistance and awareness to Indian temporary migrant workers throughout the Emirates. Another Dubai-based local civil-society group, the International Gulf Organization, has increasingly focused on migrant labor issues, particularly in the construction sector.

On the other hand, transnational civil-society groups are largely part of regional or global networks that provide legal or economic assistance to migrants in the host country. A Manila-based Filipino civil-society group—Migrante International—supports Filipino temporary migrants throughout GCC and other Middle East/North Africa (MENA) countries, including Jordan and Lebanon. These regional networks focus on facilitating legal and policy awareness of temporary migrant rights, as well as health-related issues (mainly migrant insurance schemes).

International Civil-Society Organizations

International organizations, including various United Nations agencies—e.g. the UN Development Program (UNDP), International Organization for Migration (IOM), International Labour Organization (ILO), and UNICEF—work collaboratively with governments at origin and destination, providing critical training and technical assistance to manage temporary labor migration. At times, international civil-society groups such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and ITUC serve as watchdogs. They have no primary operations based in the host country due to legal and political restrictions. As Table 1 highlights, all GCC countries permanently host UN agencies, and in some cases allow groups such as Human Rights Watch or Amnesty International to conduct migrant labor studies.

Unlicensed Civil-Society Groups

Other civil-society groups—mainly run by local citizens and temporary migrants—largely operate without government approval, making them subject to state policing. The Kuwait Human Rights Society and Kuwait Society for Fundamental Human Rights, for example, are unofficial institutions that claim that they primarily promote and protect the human rights of all individuals within Kuwait. In Bahrain, various civil-society groups such as the Bahrain Center for Human Rights and the Bahrain Youth Society for Human Rights operate as unregistered NGOs

Civil-Society Actors and the Kafala Sponsorship System: The Case of Qatar

International and transnational civil-society actors argue that the Kafala Sponsorship System—a temporary guest worker policy used to organize, govern, and control the migrant population—systematically exploits temporary migrants. Most GCC countries have not ratified a range of ILO international labor standards—mainly the right to collective bargaining and union organizing. A number of civil-society groups and, to an extent, officials in labor-sending countries, contend that the lack of ratification of these major ILO labor standards has not only made it difficult to address labor violations, but also undermined the effective implementation of certain labor standards among GCC governments.

The Qatari government has expressed an interest in establishing a foreign workers union, but this has yet to be realized.

The Right to Collective Bargaining

Various civil-society groups—particularly ITUC and the Building and Wood Workers union—argue that Qatar’s failure to ratify the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organize Convention and the Right to Organize and Collective Bargaining Convention result in labor violations and abuses. They further contend that upholding these ILO conventions would not only address minimum-wage and social protection issues, but also resolve Qatar’s ongoing failure to redress labor violations. Kuwait alone among GCC countries has ratified these two ILO conventions.

Human Rights

In February 2014, a Human Rights Watch report contended that Qatari government authorities had failed to protect the human rights of temporary migrants as a result of nonenforcement of Qatar Labor Law No. 14 and other relevant labor laws that strictly regulate private-sector labor, require companies to pay annual leave and set health and safety requirements, and mandate on-time monthly wage payments.

In addition, civil-society actors argue that the Qatari government has failed to regulate the private recruitment agencies charging exorbitant recruitment fees that inevitably led to migrants’ debt bondage. The restrictive nature of the Kafala system, which ties a migrant’s employment status and legal residence to his or her employer, gives control and power to employers, leaving migrants more vulnerable in the labor market. These civil-society groups further contend that workers’ struggles to obtain an exit visa from their employer, combined with their inability to unionize or engage in labor strikes, put them at risk.

Domestic workers in particular are more vulnerable due to their legal exclusion from Qatari Labor Law No. 14, which governs the terms of employment of the majority of individuals working in Qatar. The Qatar Foundation recently concluded that complaints of violations of the rights of domestic personnel (mainly of domestic workers) and human trafficking increased by 4 percent between 2009 and 2011.

Labor Complaints

Labor complaints and deaths have also increasingly intensified in Qatar. The Guardian newspaper reported in October 2013 that 70 Nepalese workers had died since 2012 on Qatar 2022 World Cup construction sites; in addition, ITUC has warned that as many as 4,000 migrant workers could die on construction sites absent reform to the Kafala system. The primary causes of deaths come mainly from inadequate safety equipment for workers operating on upper buildings floors, Nepalese trade unions charge.

In January 2013, ITUC and the Building and Wood Workers International union filed a complaint with ILO against the Qatari government for failure to uphold international labor standards, particularly the right to organize or unionize within the private sector. ILO is expected to release its adjudication soon, as international pressure from civil society and foreign governments intensifies.

Additionally, civil-society groups such as the Building and Wood Workers International are pressuring the Qatari government to address language-related labor violations, contending that temporary migrants—many of whom speak neither English nor Arabic—are vulnerable as a result of language barriers and the inaccessibility of complaint procedures in their language.

Recruitment Agencies

International civil-society organizations argue that the Qatari government urgently needs to regulate the abusive behavior of recruitment agencies, particularly the exorbitant illegal placement and recruitment fees they impose on migrants, as well as tighten monitoring capacity throughout workers’ contractual cycle.

Illegal Immigration and Reducing Illegal Work

Illegal immigration has continued to be a top policy concern for government and civil society alike. For civil-society actors, the large numbers of people working illegally in the GCC and MENA region make it difficult to legally protect their status and labor rights.

The Qatari government recently launched crackdowns on illegal stores and restaurants operating in several labor camps in Doha city. Hundreds of unauthorized migrant workers have been arrested as a result of increased enforcement.

Since mid-2012, the Qatari government’s Search and Follow-Up Department has increasingly conducted campaigns to identify migrants violating Qatar Residency Law No. 4, which regulates the entry and exit of expatriates. Hundreds of migrants who entered the country illegally or ran away from their sponsoring employer have been arrested, including more than 200 runaway workers apprehended by the Qatari Ministry of Interior while living in an abandoned school building in the Musherib area city. Migrants face up to three years imprisonment and penalties of 10,000 Qatari riyal (approximately US $2,700) or more for violating entry and residency laws.

More recently, Qatari government officials submitted a policy suggestion to the Gulf Cooperation Council to curb illegal migration, contending that a maid who absconds from her employer in Qatar should be legally banned by any GCC member. This policy is also being weighed by the UAE government.

In addition, illicit visa trading has also been a key concern for various civil-society actors due to growing number of migrant victims in Qatar. Recently, Qatari judges and authorities warned that illicit visa trading—in which temporary migrants “procure” visas without actual employment—has become a growing industry in its own. More than 200 court cases on illegal visa trading have been recently cited, creating an alarming concern for various civil-society actors in Qatar.

Lack of Judicial Systems and Procedures

Recently, the Qatari-run National Human Rights Committee (NHRC) urged major labor-sending countries to implement mechanisms to prevent manpower agencies from exploiting workers coming to Qatar. The committee also blamed recruitment agencies in labor-origin countries for charging excessive recruitment fees. Last year, NHRC launched a public awareness campaign for Qatari employers and workers about their rights and duties as mandated by law.

Return Migration Support

A few transnational civil-society groups have increasingly partnered with their respective governments to spread educational awareness, particularly on financial literacy, to temporary migrants. The Dubai-based Pravasi Bandhu Welfare Trust (PBWD), the Non-Resident Keralites Affairs (NORKA), and the Philippine-based Atikha Pinoy Wise Movement have launched hundreds of financial literacy workshops across the MENA region to increase financial discipline and savings among temporary migrants and their families as well as optimize their remittances.

International Community Pressure

Beyond civil-society pressure within and beyond Qatar, a number of governments and international organizations have undertaken diplomatic initiatives to ensure labor safety and protection for temporary migrants working in Qatar. British Prime Minister David Cameron, for example, urged the Qatari leadership to take immediate action to end labor violations and abuses and improve the country’s safety record. A special rapporteur for the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, François Crépeau, strongly recommended that Qatar abolish the Kafala system, implement more stringent labor standards, and permit migrant workers to form unions. The International Federation of Association Football (FIFA), organizer of the World Cup, has vowed to increase monitoring and investigations to ensure justice for construction workers in Qatar alleging labor violations or other abuse.

Qatari Government Initiatives

Under growing international pressure, the Qatari government has increasingly moved to reform various labor policies and programs to improve the general welfare and working conditions for migrants. These recently implemented government actions have gained increasing public support and attention. In 2013, the Qatar Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy (QSCDL) reinforced its commitment to upholding international labor standards to increase protections for migrant workers.

Even as they are addressing civil society’s concerns and recognize the validity of the complaints, Qatari authorities have expressed some frustration that their efforts to improve migrants’ welfare are not being fully recognized, nor are their challenges in managing high-migrant population rates.

Increased Standards

Qatar recently has shown some commitment to increasing labor protections and addressing labor violations. The Qatar Foundation, a semi-private organization founded by the royal family, in 2013 released a set of detailed standards for the treatment of migrants employed by the foundation and its contractors and subcontractors. Civil-society groups say that for these and other standards to be effective, however, the government must increase monitoring of the subcontractors that predominate on construction sites. These groups argue that inadequate monitoring is the systematic root of the problem. They blame insufficient monitoring for some employers’ refusal to pay workers their wages—a situation aided by the fact that in Qatar, migrant workers are paid in cash (not via an electronic wage payment system such as used in the United Arab Emirates). Nearly 90 percent of labor complaints from runaway domestic workers are for nonpayment, according to the Philippine Embassy in Qatar.

Temporary Labor Migrants Union

The Qatari Ministry of Labor in December 2012 discussed establishment of a foreign workers union, yet this has not materialized due to ongoing pressures and tensions from civil-society actors in Qatar. Furthermore, a bid by the government to scrap the Kafala system and replace it with foreign workers’ unions is also in limbo. ITUC argued strongly that this arrangement would further exacerbate exploitation, as temporary migrants still would have to obtain permission from their employer before leaving the country.

Standardized Labor Employment Contracts for Domestic Workers

The GCC countries are considering creation of a unified job policy to streamline and unify terms and conditions of employment contracts for domestic workers across the region. The UAE and Bahraini governments, for example, are preparing legislation to protect domestic workers’ rights by addressing passport confiscation and nonpayment of wages. These proposed legislative reforms are expected to be reviewed this year, given ongoing diplomatic discussions with labor-sending country officials.

A GCC Regional Perspective on Civil-Society Actors

International Dialogue

Various civil-society actors have recognized a new openness to labor and human-rights reforms to various degrees within the GCC region. The UAE government, along with 20 labor-sending and receiving countries, for example, facilitated the Abu Dhabi Dialogue, established in 2008, to better maximize the potential of labor migration as a development strategy. The current focus of Dialogue members is to identify the primary obligations and roles of both sending and receiving governments, as well as the private sector, throughout the labor migration cycle.

Civil-society groups have also looked with approval on the UAE government’s other policy efforts, including its recent Labor Mobility and Development Conference in Abu Dhabi, where more than 150 policymakers, researchers, and experts were invited to identify policy approaches and solutions to optimize migration for all. These particular efforts are not only seen as vital interests to the GCC governments, but also partly attributable to the growing need to critically engage with international civil-society groups and uphold commitments to international labor standards.

Regional Kafala Sponsorship System

While civil-society groups generally consider the GCC region’s Kafala Sponsorship System exploitative, they also recognize the diverging policy differences between and among GCC countries. In Kuwait, for example, temporary workers can change employers after working under a sponsor for three years, while in Bahrain, temporary workers can change sponsors after one year.

In Qatar, a number of civil-society groups are extremely critical of the government because temporary migrants must seek legal permission from their sponsors to change employers, which gives employers more power to determine the migrant’s mobility. This makes some temporary workers “absconders,” inevitably subjecting them to immediate detention and deportation or denial of exit visas.

Institutional Initiatives

Given the increasing attention from civil-society actors, some GCC governments have increasingly enhanced their capacity to examine the scope, scale, and activities of these institutions. In 2008, the UAE government established the Community Development Authority—a government agency which regulates the activities of all civil-society actors—and recently passed a law requiring all formal and informal civil-society groups to register with the Authority. One CDA official estimates that more than 30 civil-society groups have recently obtained licenses, but other informal groups—mainly migrant-led—have had difficulty getting licensed due to certain financial and administrative legal requirements.

In response to civil society’s demands, the Qatari government assigned the Migrant Workers Welfare Center to increase enforcement of Labor Law No. 14 and improve living and working conditions of migrant workers.

Resistance and Future of Civil Society in the GCC Region

Since the Arab Spring, GCC governments have increasingly scrutinized official and unofficial civil-society groups and their institutional affiliations in the region. As qualitative interviews suggest, these actual and perceived fears come from the governments’ extensive experience with certain civil-society groups using human rights to assert personal interests or extend Western political agendas into the GCC/MENA region.

The demographic imbalance—characterized by migrants’ high share of total population—poses critical challenges to the GCC governments, as migrant populations potentially could mobilize against them. A number of GCC governments contend that international civil-society actors fail to take into account local GCC culture and values. To an extent, these civil-society critiques err in homogenizing the GCC region as a monolithic entity. From the governments’ perspectives, they view international civil-society groups as more interested in using a combative approach over collaboration, often holding deeply biased and politicized views about the region and lacking understanding about the many nuances of labor migration.

As a result, GCC governments have limited their partnerships with international civil society. These organizations have turned elsewhere to achieve reform, increasingly exerting pressure on relevant partners—including foreign governments, international associations, and unions—to create the momentum for GCC governments to come closer toward international labor standards and improve protections for migrant workers.

Ultimately civil society and increasingly some in GCC governments recognize that structural and legal reforms to the Kafala Sponsorship System are imperative for improved labor protection, as is greater compliance with international labor standards. While structural reforms can significantly improve current institutional and policy arrangements in some GCC governments, ongoing state and nonstate diplomacy and collaborations are more critically imperative to enhance mutual and long-term relationships and collaborations in the 21st century.

Sources

Al Sayed, Khalid. 2013. Civil societies in the Gulf and future vision. The Peninsula, September 12, 2013. Available online.

Al Youha, A. and Malit, Jr. Froilan T. 2013. Gulf Labor Policies need context. Al-Monitor, February 17, 2014. Available online.

Amnesty International. 2013. Qatar: FIFA must not tolerate human rights abuses on construction projects for 2022 World Cup. Press release, November 17, 2013. Available online.

ANSAmed. 2013. Qatar: abused domestic workers on the run. ANSAmed, September 10, 2013. Available online.

---. 2013. Qatar Emirate opens to foreign workers’ union. ANSAmed, December 3, 2013. Available online.

Asian Tribune. 2012. Good News for Migrant Workers – Qatar to Drop Sponsorship and adopt recruitment on Contract System. Asian Tribune, May 6, 2012. Available online.

Booth, Robert. Qatar World Cup 2022: 70 Nepalese workers die on building sites. The Guardian, October 1, 2013. Available online.

Building and Wood Workers’ International. 2012. BWI and ITUC Files Joint CFA Complaint Against Qatar. Release, September 28, 2012. Available online.

Colombo Process. Undated. Abu Dhabi Dialogue. Accessed April 4, 2014. Available online.

Community Development Authority. Undated. About Us. Accessed April 4, 2014. Available online.

Devasia, T.K. 2012. Self-help best option for returnees. Khaleej Times, November 23, 2012. Available online.

Doha News. 2013. Unions file case against ‘forced labor’ in Qatar with UN agency.

Doha News, January 18, 2013. Available online.

Doherty, Regan. 2012. World Cup puts spotlight on labor rights in Qatar. Reuters, June 20, 2012. Available online.

Ekantipur. 2014. Qatar introduces workers’ welfare. Ekantipur, February 13, 2014. Available online.

Fargues, Philippe and Shah, Nasra. 2012. Socio-economics Impacts of Migration. Cambridge, UK: Gulf Research Centre Cambridge. Available online.

Gibson, Owen. 2013. Qatar 2022 World Cup Workers treated like cattle. The Guardian, November 17. Available online.

Gulf News. 2013. Abu Dhabi hosts labor mobility conference. Gulf News, April 29, 2013. Available online.

Hindustan Times. 2012. Qatar calls for unified job policy for Gulf nations. Hindustan Times, January 3, 2012. Available online.

Human Rights Watch. 2013. Proposed Domestic Workers Contract Falls Short. News release, November 17, 2013. Available online.

---. 2014. Qatar: Serious Migrant Worker Abuses. News release, January 21, 2014. Available online.

---. World Report 2014 – Qatar. New York: Human Rights Watch. Available online.

Malit, Jr. Froilan T. and Al Youha, A. 2013. Labor Migration in the United Arab Emirates: Challenges and Responses. Migration Information Source, September 18, 2013. Available online.

Malit, Jr. Froilan T. 2013. Inside the Labor-Sending State: The Role of Frontline Welfare Workers and Informal Migration Governance in Qatar. Cornell University Industrial and Labor Relations Working Paper No. 163. Available online.

McGinley, Shane. 2012. Qatar to establish first labor union. Arabian Business, May 24, 2012. Available online.

Migrante International. Undated. About Us. Accessed April 4, 2014. Available online.

National Human Rights Committee. Undated. About NHRC – Vision and Mission. Accessed April 4, 2014. Available online.

Peninsula, The. 2012. Recruitment Agencies seek bigger role. The Peninsula, October 2012. Available online via the Asian Pacific Migration Network.

---. 2012. Qatar needs one million foreign workers for 2022 projects: ILO. The Peninsula, October 15, 2012. Available online.

---. 2012. NHRC chief calls on countries to protect migrant workers’ rights. The Peninsula, December 12, 2012. Available online.

---. 2012. 200 runaway workers held in swoop. The Peninsula, December 6, 2012. Available online.

---. 2013. Victims file cases against ‘visa traders.’ The Peninsula, October 15, 2013. Available online.

---. 2013. Crackdown on illegal restaurants, stores. The Peninsula, November 25, 2013. Available online.

Qatar Foundation. 2013. QF Mandatory Standards of Migrant Workers' Welfare for Contractors and Sub-Contractors. Available online.

Rahman, Fareed M.A. 2011. Indian rights workers visit UAE jails. The National, December 8, 2011. Available online.

Shane, Daniel. 2012. Trade unions reject Qatar labour proposals. Arabian Business, May 5, 2012. Available online.

Sheshtway, Mostafa. 2012. Qatar cracks down on housemaids violating law. Gulf News, July 1, 2012. Available online.

Trade Arabia. 2013. GCC plans new law for domestic workers. Trade Arabia, December 16, 2013. Available online.

U.S. Department of State. 2013. Bahrain 2012 Human Rights Report. Washington, DC: Department of State. Available online.

---. 2013. Kuwait 2012 Human Rights Report. Washington, DC: Department of State. Available online.

---. 2013. Oman 2012 Human Rights Report. Washington, DC: Department of State. Available online.

---. 2013. Saudi Arabia 2012 Human Rights Report. Washington, DC: Department of State. Available online.

---. 2013. Qatar Human Rights Report. Washington, DC: Department of State. Available online.

---. 2013. United Arab Emirates 2012 Human Rights Report. Washington, DC: Department of State. Available online.

World Bank. 2013. Defining Civil Society. Last updated July 27, 2013. Available online.