Working Hard for the Money: Bangladesh Faces Challenges of Large-Scale Labor Migration

Bangladesh, meaning "Bengal nation," is a low-lying country located on the Bay of Bengal between Burma and India, and has a territory of nearly 57,000 square miles (147,570 square kilometers). Bangladesh emerged as an independent state in 1971, separating itself from Pakistan after nine months of bitter conflict with enormous casualties of Bengali civilians.

Bangladesh boasts a population of 158 million people, making the rather small country the seventh most populous in the world and one of the most densely populated. With a majority Muslim Sunni population (85 to 90 percent), Bangladesh is also the third largest Muslim-majority country in the world, after Indonesia and Pakistan. The vast majority of the citizens of Bangladesh self identify as ethnically Bengali, though tribal groups concentrated mainly in the regions bordering Burma are also part of the country's landscape.

Bangladesh has registered a 5 to 6 percent rate of annual economic growth since the mid-1990s, and has made important progress in the areas of primary education, population control, and the reduction of hunger. Despite these positive developments, however, poverty in Bangladesh is widespread, affecting the lives of perhaps half of the population. In this predominantly rural country, overpopulation and environmental degradation have contributed to a large, landless population.

About 61 percent of the population of Bangladesh is of working age (15 to 64-years-old), while 34 percent is under the age of 14, indicating a moderate youth bulge. Those who are employed in the formal labor market often work just a few hours a week at low wages. Thus, while the estimated unemployment rate is relatively low at about 5 percent, the problem of underemployment prevails.

Widespread poverty, underemployment, and a youthful age structure have all contributed to the predominance of economically motivated international migration from Bangladesh. The contract labor migration of less-skilled men to the Arab Gulf states and to the emerging economies of Asia has been especially prominent. Though these temporary movements in which workers are authorized by receiving countries to work for legally specified periods of limited duration have been integral in contributing to the economy of Bangladesh, this migration stream comes with its own set of problems.

This profile offers a broad overview of trends in international migration for Bangladesh as a migrant sending country, with particular emphasis on contract labor migration and the policy challenges that it poses for the Bangladesh state.

Contract Labor Migration from Bangladesh

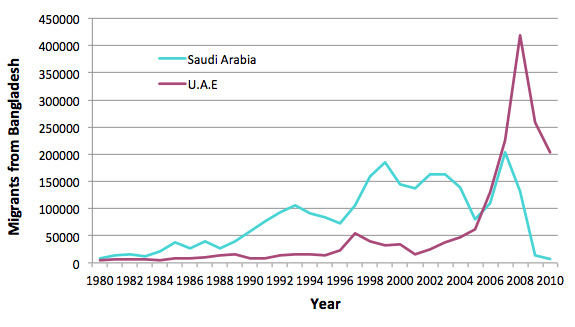

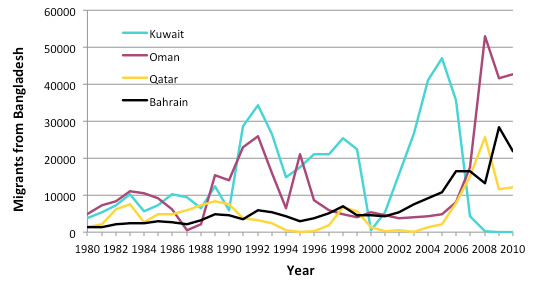

Since the 1980s, Bangladesh has been an increasingly important source country in international flows of contract labor migration. The primary destinations for Bangladeshi migrants have been the Arab Gulf states, particularly members of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). According to the official figures of the Bureau of Manpower, Employment, and Training (BMET) of the Government of Bangladesh, over 5 million Bangladeshis migrated to work in the GCC states between 1976 and 2009, with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates being the top country destinations.

International labor migration from Bangladesh began to expand in the 1990s beyond the GCC states, however, to include a wider range of countries including Japan, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mauritius, Singapore, and South Korea. Of these newer destinations, Malaysia has been the most important, officially receiving 698,736 Bangladeshi workers from 1976 to 2009.

|

|

||

|

|

|

||

|

According to BMET, the vast majority of Bangladeshi workers who migrated between 1976 and 2008 were unskilled and skilled laborers. Unskilled laborers such as domestic and agricultural workers constituted 50 percent of the outflow of labor migrants from Bangladesh during that time, while skilled workers such as manufacturing and garment workers, computer operators, and electricians made up 31 percent of labor migrants.

Both semi-skilled workers and professionals also participate in international labor migration from Bangladesh, but to a lesser extent. From 1976 to 2008, semi-skilled workers such as tailors and masons comprised 16 percent of outflows, while professionals such as doctors, engineers, teachers, and nurses constituted just 2.9 percent.

Due to former government policies restricting the labor migration of women, the overwhelming majority of Bangladeshi labor migrants have been men. From 1997 to 2003, women made up less than 1 percent of the worker outflow from Bangladesh. There are, however, signs of a slight shift away from this gender imbalance. Though the migration bans had arisen from concerns about the potential for Bangladeshi women workers to become victims of sexual exploitation and human trafficking while migrating or residing abroad, the government of Bangladesh lifted the ban limiting the labor migration of women in 2007. By 2008 – just one year later – the share of female migrants going abroad to work had risen to 5 percent of the total.

Remittances

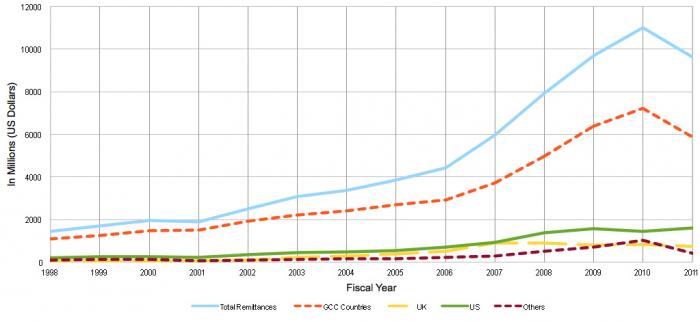

Since the 1990s, remittances have played an increasingly important role in the national economy of Bangladesh. As shown in Figure 2 below, remittances grew steadily in the opening years of the 21st century. Although at a more moderate pace, the growth trend continued in the face of the global financial crisis of the late 2000s and the uprisings taking place in the Middle East in late 2010 and throughout 2011.

|

|

||

|

A large proportion of remittance flows to Bangladesh come from the earnings of Bangladeshi workers in GCC countries. As a result, the recent political unrest gripping much of the Middle East has emerged as an important policy issue in Bangladesh. Fears about how the Arab Spring may negatively impact remittance flows into the economy have been encouraged by the observed drop in the official numbers of Bangladeshis going abroad as contract workers in 2010.

Contrary to these expectations, however, official remittances to Bangladesh in fiscal year (FY) 2011 were the highest in the country's history, rising 6 percent from the previous year to total over $11.5 billion, and representing about 13 percent of the country's gross domestic product (GDP). Remittances were more than nine times the level of foreign direct investment flows into the country and also about four times more than the total foreign aid received.

This somewhat unexpected outcome may be explained by the return migration of many Bangladeshis from the Middle East, most of whom would have brought their assets and savings with them upon their return. An additional factor explaining the high numbers is that those remaining in the Middle East have likely been more inclined to remit money home instead of saving in their countries of sojourn due to anxieties about conditions there.

Moreover, both government and private commercial banks have strengthened programs designed to encourage expatriate Bangladeshis to remit through formal banking channels instead of informal ones, making those funds remitted more easily traceable.

Challenges Posed by Contract Labor Migration

The rise of international labor migration has posed increasingly complex and pressing political challenges for the Bangladesh state. Given the economic significance of remittances, the facilitation of overseas labor contracts for citizens has been a critical issue. But the state has also faced growing political pressures to take on a more vigilant and effective role in ensuring the rights and well-being of its citizens abroad, especially concerning migrant worker exploitation and widespread prejudices against Bangladeshi workers, the latter contributing to the already unpredictable nature of overseas labor markets.

Human rights advocates have been particularly vocal in their calls for migrant worker protection, bringing attention to the vulnerability of less-skilled Bangladeshi workers to abuse and exploitation while they are abroad. Types of abuse range from exploitive employment and pay practices to physical and sexual abuse. Many of these problems are traced to the dysfunctional dynamics of the recruitment system for Bangladeshi workers, especially considering the high levels of corruption at play within it.

In the official system, recruitment begins with potential overseas sponsors stepping forward. They are expected to guarantee jobs for Bangladeshi workers, either in their own businesses or in those of others to whom they are providing the service of procuring foreign labor. Recruiting agencies in Bangladesh that belong to the Bangladesh Association of International Recruiting Agencies (BAIRA) function as intermediaries, matching overseas employers with Bangladeshi workers.

The recruiting agencies are expected to assist workers in signing contracts with the sponsor that specify the terms of employment, such as the type of job, pay, hours, provisions for leave, and other conditions. Travel and work visas are issued only after all of the relevant documents are inspected and approved by government officials in both the sending and receiving countries.

In Bangladesh, as in many other migrant sending states, the recruitment of less-skilled workers for overseas jobs has become a large and lucrative transnational industry – one that straddles the labor-sending and labor-receiving states. The industry is composed of an array of intermediary services in the foreign worker recruitment and placement process, including entrepreneurial “scouting” agents who locate would-be migrants in rural parts of the country. These agents negotiate on behalf of potential migrants with the recruiting agencies, which in turn negotiate with the international sponsoring companies and other intermediaries in Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, and other migrant-receiving states.

As labor migration outflows from Bangladesh have grown, so too have the components of the transnational recruitment industry. The intermediary service nodes have multiplied, resulting in higher transaction costs that tend to be passed down to migrants.

According to a 2009 national survey by the International Organization for Migration in Bangladesh, intermediaries such as scouting agents generated almost 60 percent of the costs of going abroad for Bangladeshi labor migrants. These costs were the highest in South Asia.

Underlying the high costs for less-skilled Bangladeshis to go abroad to work is widespread corruption within the transnational recruitment industry. Intermediary service providers may engage in dishonest practices that involve the transnational collusion of multiple businesses as well as government officials. Among other things, corrupt practices result in the production of false sponsorship documents for workers.

The illegal practices and high costs imposed by the transnational recruitment industry have contributed to the growth of an undocumented population of Bangladeshi workers in the GCC states and other receiving nations. Such a high-risk and high-cost enterprise means that employers may prefer to hire an undocumented migrant worker over a documented one, thus avoiding the relatively large expense of recruiting workers from abroad.

For less-skilled Bangladeshi workers, the high costs of arranging employment abroad may encourage them to overstay their work visas once they have migrated. In addition, the corruption of the recruitment industry has led to cases of workers unwittingly purchasing fraudulent documents, only to find that they are unauthorized immediately upon arrival to their destination.

Under these conditions, less-skilled workers from Bangladesh are at an increased risk of forced labor, exploitation, abuse, and even human trafficking in their destination countries. Some find themselves in situations of forced labor or debt bondage where they face restrictions on their movements, non-payment of wages, threats, and physical or sexual abuse.

The vulnerability of less-skilled Bangladeshi migrant workers to exploitation, especially for those who are unauthorized, is also the result of negative public attitudes towards them in receiving societies. In a study of less-skilled Bangladeshi labor migrants in the GCC states and Malaysia, it was found that they often encounter discrimination and an overall stigma associated with being Bangladeshi. Migrants reported the presence of negative popular stereotypes of Bangladeshi workers as unruly and prone to participating in criminal activity.

These unfavorable attitudes have contributed to the irresolute reception that has marked less-skilled labor migration flows from Bangladesh. As highlighted by the ongoing (as of this writing) political crisis in Libya that has forced Bangladeshi and other foreign workers there to flee, migratory movements are inherently unpredictable. In the case of Bangladesh however, this element of intrinsic volatility is exacerbated by the periodic bans that have been imposed by receiving countries on the recruitment and entry of less-skilled labor from Bangladesh.

In Kuwait, for example, a ban was imposed on Bangladeshi workers in 1999 and lifted in 2000 only to be reinstated in 2006 and again in 2008. In 1994, Malaysia agreed to recruit Bangladeshi workers, but it banned them from entry in 1997. The doors reopened ten years later in 2007, but closed again in 2009. Saudi Arabia, the largest overseas labor market for Bangladeshi migrant workers, has worked to reduce the number of resident Bangladeshis since 2008, though it has not moved to ban them altogether.

While declining labor market demand and other legitimate factors may inform these periodic shifts away from welcoming Bangladeshi workers, widespread antipathy towards them has also played a role. The bans have been driven in part by political concerns and public anxieties in receiving societies about the disruptive presence of Bangladeshis, especially those who are unauthorized.

Other Destinations: India and the Global North

In addition to contract labor migration, there are other types of movements that are part of the larger landscape of international migration in Bangladesh.

Driven by cross-border trade industries and other economic opportunities, there are irregular and circular migration streams to and from neighboring India. This migration is also informed by the shared histories of Bangladesh and India, and the presence of long-standing communities that straddle the borders of the two countries.

These cross-border movements have, however, been a key point of tension in India-Bangladesh relations. In India, there is anxiety about unauthorized migration from Bangladesh and its social and political consequences. Indian border guards have shot and killed Bangladeshi civilians along the border – causing public outcry in Bangladesh – and the Indian government is currently erecting a barbed wire fence along the border in an effort to stem illegal trade and migration.

International migration from Bangladesh today also includes movements towards the developed world. Bangladeshi diaspora communities have emerged in Australia, Canada, Great Britain, Italy, and the United States, among other countries. Unlike contract labor migration, these movements have involved the permanent settlement of families, and predominantly involve Bangladeshis from urban and middle-class backgrounds.

Of these migratory flows to the global North, the one to Great Britain has the longest and most distinctive history. The 1948 Nationality Act in Britain, passed at a time of labor shortages within the country, allowed unrestricted entry to Great Britain for the citizens of the realm's former colonies, including present-day Bangladesh.

Bengalis participated in the larger trends of migration from South Asia to Britain following the passing of the act, though less extensively than persons from India and West Pakistan due to the discriminatory policies of the Pakistani government towards the Bengalis of East Pakistan. Such discriminatory practices included the denial of passports to Bengalis in an attempt to restrict their overseas travel.

The Bengalis who did make it to Britain in the post-World War II years were largely young men from rural backgrounds with relatively low levels of education. They were also largely from Sylhet in Northeastern Bangladesh, a fact that has given the British Bangladeshi community a distinct regional identity that remains prominent to the present day.

In the 1960s and 1970s, as British immigration policies were becoming increasingly restrictive, Bengali migrant men already present in Great Britain began to resettle their families there. As a result, there are over 350,000 persons of Bangladeshi origin in Britain today.

Following Great Britain, the United States is home to the second largest Bangladeshi diaspora community in the global North. In fact, current rates of Bangladeshi migration to the United States are higher than they are to Britain, indicating that the Bangladeshi-origin community of the former is likely to grow to outnumber the one of the latter in the near future.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, in 1980 there were 5,880 foreign born from Bangladesh in the United States. The number of Bangladeshis then rose rapidly over the next two decades, from 21,749 in 1990 to 92,237 by 2000. These numbers, of course, do not take into account the presence of unauthorized Bangladeshi migrants in the United States.

Employment-based immigration and family sponsorship are the most important categories under which Bangladeshis migrate to the United States, though the Diversity Visa Lottery has also contributed to the growth of the Bangladeshi-American community since 1990. Popularly known as the green card lottery, the program strives to ensure diversity in migrant origins and consists of a visa lottery that is only open to prospective immigrants from countries that have sent fewer than 50,000 people to the United States in the previous five years.

State Response to Migration's Challenges and Opportunities

The Bangladesh government has been increasingly attentive to relations with the country's diaspora, particularly with the growing numbers of Bangladeshis settled abroad in North America, Europe, and other parts of the developed world. In this they have been encouraged by the large contributions of the Chinese and Indian diasporas to their countries of origin: two of the world's most important emerging economies.

To that end, Bangladesh has established the Non-Resident Bangladeshi (NRB) category to refer to those who were born in Bangladesh but are now permanent or long-term settlers abroad. Among the privileges of having NRB status is special eligibility for restricted foreign currency bank accounts in Bangladesh. And when traveling to Bangladesh, NRBs are not required to pay visa fees.

The standing dual nationality policy of Bangladesh has served to institutionalize NRB status. The policy allows those who are foreign citizens of Bangladeshi origin (as well as children born to them) to become citizens of Bangladesh or to affirm their citizenship. Since the early 2000s, segments of the diaspora have also vigorously lobbied – so far unsuccessfully – for the extension of voting rights for elections in Bangladesh.

These concessions for the diaspora notwithstanding, the primary focus of the Bangladesh government with respect to migration policy has been on contract labor migration, the major source of remittances (and economic growth) for the country.

Successive governments in Bangladesh have tried to secure and expand outflows of labor migrants through diplomatic negotiations with labor receiving countries. The Bangladesh government has also expanded institutions devoted to the regulation of “manpower export,” or international labor migration.

In 1990, the government set up the Wage Earners Welfare Fund with the goal of creating a central pool from which to assist migrant workers and their families in emergency situations. The fund is largely financed through mandatory contributions of migrant workers.

Then in 2002, the Ministry of Expatriates Welfare and Overseas Employment was created with the goal of facilitating labor migration, exploring new labor markets, and ensuring the welfare of Bangladeshi migrant workers. The Ministry oversees the BMET, the government agency in charge of registering and clearing labor migrants for overseas employment.

Four years later, the government of Bangladesh announced the creation of the Overseas Employment Policy (OEP). Produced in 2006 in consultation with NGOs devoted to human rights and migrant welfare, the OEP is a comprehensive policy brief on international labor migration that affirms the goal of expanding overseas employment as a strategy of economic development for Bangladesh.

More specifically, the OEP acknowledges that overseas employment alleviates the problems of unemployment and underemployment in Bangladesh, and that remittances may alleviate poverty and fund investments in housing, health, and education.

A wide range of policy goals is outlined in the OEP, including the strengthening of official remittance channels and the expansion and maintenance of overseas markets. Also discussed are measures for the training and protection of migrant workers, including reintegration after their return to Bangladesh.

While many of the OEP's specific recommendations still await implementation, the government of Bangladesh announced plans in 2011 to open an Expatriate Welfare Bank. The bank will offer loans to those who wish to go abroad and will provide remittance and job training services.

Despite these gains, however, Bangladesh has not ratified the 1990 UN Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families. Though Bangladesh is a signatory to the convention, ratification has been likely been blocked by fears that it might discourage the governments of labor receiving nations from recruiting Bangladeshi laborers for work in their countries.

Sources

Central Bank of Bangladesh. Economic Data: Wage Earners Remittance Inflows: Various tables. Dhaka: Government of Bangladesh. Available Online.

Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training (BMET). Statistics: Various tables. Dhaka: Government of Bangladesh. Available Online.

Kibria, Nazli. 2011. Muslims in Motion: Islam and National Identity in the Bangladeshi Diaspora. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Martin, Philip. 2010. Background Paper WMR 2010 The Future of Labour Migration Costs. Geneva: International Organization for Migration. Available Online. .

Peach, Ceri. 2006. South Asian migration and settlement in Great Britain. Contemporary South Asia 15: 133-146.

Shaham, Dahlia. 2008. Foreign Labor in the Arab Gulf: Challenges to Nationalization. Al Nakhlah: The Fletcher Online Journal of Southwest Asia and Islamic Civilization Fall. Available Online.

Siddiqui, Tasneem. 2006. International Labour Migration from Bangladesh: A Decent Work Perspective. Working Paper No. 66. Geneva: International Labor Organization. Available Online.

Siddiqui, Tasneem. 2007. Ratifying the UN Convention on Migrant Worker Rights. The Daily Star, December 18, 2007. Available Online.