You are here

Global Demand for Medical Professionals Drives Indians Abroad Despite Acute Domestic Health-Care Worker Shortages

Indian nurses in class. There were more than 1.6 million nurses registered in India in 2015. (Photo: Aravind Eye Care System)

India has been the world’s largest source for immigrant physicians since the country gained independence in 1947. Around 69,000 Indian-trained physicians worked in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia in 2017, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which is equivalent to 6.6 percent of the number of doctors registered with the Medical Council of India (MCI). The country, which boasts the world’s highest number of medical schools, also has become a leading source for nurses (typically trailing only the Philippines). Nearly 56,000 Indian-trained nurses work in the same four countries, equal to about 3 percent of the registered nurses in India. The allure of working abroad is strong for both physicians and nurses; researchers estimate anywhere from 20 percent to 50 percent of Indian health-care workers intend on seeking employment overseas for a range of reasons.

Several countries have encouraged Indian health-worker migration in recent years. In the United Kingdom, for example, a fast-tracked visa for medical professionals was announced in November 2019. The visa would aim to address shortages in the country’s National Health Service (NHS). More than 15,000 doctors in the NHS as of 2017 had received their primary medical qualification in India, and Indians represented the top non-British nationality for NHS staff as of early 2019.

Even as Indian medical professionals are drawn internationally by affirmative policies and perceived better opportunities, less than optimal conditions at home also drive their decision to leave. Among the factors: the central government’s lack of investment in health care, limited residency spots available for graduate doctors, frustration linked to bureaucratic bottlenecks in appointing senior medical professionals, and the perceived importance of building professional status through international residencies and training opportunities.

Against this global pull, the Indian government has undertaken a number of policies to limit the emigration of doctors and nurses, though these have been more ad hoc in nature and not part of a fully realized strategy. Based on these changes it seems fair to say that the Indian government has realized the downside of sizeable migration of health-care professionals; the effectiveness of its policies remains questionable.

The global migration of doctors and nurses has generated considerable debate regarding the impact of this process on both sending and receiving nations’ health-care systems. In India, issues of “brain drain” and the need for an adequate stock of medical professionals inform media and policy debates. These issues are cast into further relief in the context of India’s critical shortfall of domestic health-care workers (3.3 qualified allopathic doctors and 3.1 nurses and midwives per 10,000 population—well below the World Health Organization (WHO) benchmark of 22.8 doctors, nurses, and midwives per 10,000). Overall, looking at all skilled health-care personnel, the ratio in India was 28.52 professionals per 10,000 residents in 2016, compared to 52.82 globally.

This article analyzes India’s role in the global provision of health professionals by exploring their international migration, considering established and emerging patterns of migration, and presenting relevant policy creation. While these issues affect a range of health occupations, the article focuses in particular on doctors and nurses.

The Indian Health-Care Context

The health-care sector in India, which is the world’s second most populous country with more than 1.35 billion residents, has been expanding since the post-independence period. This has particularly been the case in the 1990s post-liberalization era, which saw private capital leading the expansion of the health-care sector. The number of registered medical colleges has soared, from 86 in 1965 to 539 in 2019; annually, more than 67,200 students begin bachelor of medicine and bachelor of surgery (MBBS) programs. Current projections suggest there will be 1,493,385 registered doctors in India in 2024, which would meet the WHO-recommended ratio of one doctor per 1,000 individuals. Yet despite this rapid expansion, the urban concentration of health services and medical professionals remains a challenge in a country where two-thirds of the population still live in rural areas.

The MCI is the main regulatory body for the western, allopathic form of medical treatment (the use of medications or surgery to suppress or treat disease). The more traditional medicines, including ayurveda, yoga and naturopathy, unani, siddha, and homoeopathy (AYUSH), are regulated by the Ministry of AYUSH. In order to be recognized as legal practitioners, all allopathic or ayurvedic doctors must be registered with these institutions; however, researchers suggest that as many as 25 percent of Indians receive medical treatment from unlicensed providers, especially in rural areas. India’s health-care workforce includes allopathic doctors (31 percent); nurses and midwives (30 percent); pharmacists (11 percent); practitioners of AYUSH (9 percent); ophthalmic assistants, radiographers, and technicians (9 percent); and others (10 percent). Despite public concern regarding corruption in MCI—which is caused in part by the extreme gap between the supply and demand for medical education—central-government efforts to reform this sector have been slow.

Nursing and midwifery are regulated by the Indian Nursing Council and the respective state nursing councils. Nurses complete either a three-and-a-half-year diploma in general nursing and midwifery or a four-year bachelor’s degree and are registered with the council. The number of nursing colleges increased from 30 in 2000 to 1,650 in 2015, with much of this capacity in private institutions. New calculations based on National Sample Survey (NSS) and registration data indicate that in 2015 there were more than 1.6 million nurses registered in India, or about 4.2 nurses per 10,000 people. The nursing profession in India has long been neglected, positioned as subservient to the medical hierarchy. Salary and working conditions are generally poor, especially in the growing private hospital sector, with limited opportunities for continued professional development. These factors (career progression, professional status, and income) are among the reasons nurses seek opportunities overseas.

International Migration of Indian Medical Professionals

Popular destinations for Indian health professionals include the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.

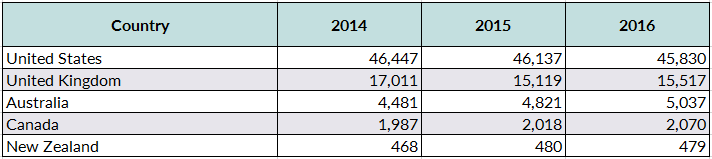

Table 1. Top Five Countries of Destination for India-Trained Doctors, 2014-16

Source: OECD Statistics, Health Workforce Migration, “Foreign-Trained Doctors by Country of Origin – Stock,” accessed January 16, 2020, available online.

English is the language of instruction for most Indian health training institutions, which facilitates international migration. While India tops the number of internationally trained doctors in the United States and the United Kingdom, the share of internationally educated health professionals (IEHPs) in these two countries declined between 2000 and 2014 due to increased production of domestic graduates and the lingering effects of the global financial crisis. International migration continued to grow for other destinations—including most OECD countries.

Furthermore, 57 percent of nurses migrating from the Indian state of Kerala resided in Gulf countries in 2016 (with Saudi Arabia the top destination). Saudi Arabia’s health-care system is heavily reliant on IEHPs, with Saudi nationals comprising just 32 percent of physicians and 38 percent of nurses in the country in 2018. Other countries with a significant share of Indian-trained nurses include the United States (6 percent of the overall nursing workforce in 2016), Canada (5.5 percent), and a smaller share in Australia, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Maldives, and Singapore (2 to 3 percent). Ireland is one example of a new market that developed for Indian-trained nurses, with 35 percent of nurse recruitment into the country between 2000 and 2010 coming from non-European Union sources.

Training Patterns Often Determine Migrants’ Destinations

As mentioned earlier, the post-liberalization era has seen private investment dominate health education expansion in India. Several health corporations, such as Apollo Hospital chain and Fortis Group, are involved in training, and are funded through private capital from Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) or returning migrants. Indian corporate health groups value international training and experience; indeed, many have international partnerships that facilitate health-worker exchanges, and they leverage their internationalism to promote medical tourism to India. Additionally, international agencies (such as Joint Commission International for hospitals, United States Medical Licensing Examination for doctors, and National Council Licensure Examination testing centers for nursing) see India as an important growth market, and their presence adds to the internationalized environment that encourages health professionals to consider international migration options.

Private investment has influenced the expansion of training institutes: an estimated 95 percent of Indian nursing institutes are private, and just more than half of all medical college positions are in the private sector. These institutes have emerged in part to service the increased interest by health-care professionals in response to international migration opportunities, yet they have also created a kind of migration debt trap for some, particularly nurses. Private training institutes generally cost more than government ones, and these costs eventually become an important migration driver, since domestic salaries are too low to cover educational debts. The high cost of migration—which includes fees paid to local recruiting agents—is ultimately outweighed by the prospective salaries and benefits earned abroad. Using purchasing power parity, researchers have found that U.S. nursing and physician salaries are 80 percent and 57 percent higher than comparative Indian salaries.

The competitiveness of medical education and the potential rewards from international opportunities are driving would-be health-care professionals unable to enter Indian programs of study to opt for degrees in Russia, China, and Eastern European countries. According to the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, in 2018 approximately 18,000 Indian students were enrolled in Chinese universities and around 11,000 in Russian universities—mostly in medical programs. To practice in India these students must pass the foreign medical graduate exam (FMGE), which the majority fail. Further research is needed to reveal if this offshoring of Indian medical students will become part of an international multistep migration pathway rather than just a route back to India.

The Dawn of Policies to Control and Limit Migration

The Indian government has advanced a number of policies to regulate and limit the emigration of health workers in recent years. Yet these seem to be mostly a patchwork of bureaucratic reforms instead of a centralized policy framework designed to balance the country’s health-care worker needs with policies to better facilitate emigration.

Limiting Doctor and Nurse Migration

In order to limit the migration of doctors, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare decided in 2011 to stop issuing a No Obligation to Return to India (NORI) certificate, which is necessary for medical graduates who wish to apply for a J-1 visa to the United States. The ministry explicitly cited an acute shortage of doctors, due to large-scale emigration, in making the announcement. In response, the Maharashtra Association of Resident Doctors (MARD) challenged the decision in the Bombay High Court, which termed the policy unfair but left it in place.

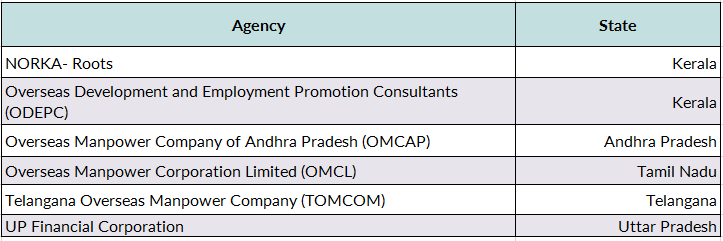

Nurse emigration has similarly been subject to bureaucratic restrictions, including nursing institutions’ imposition of bonds on students if they fail to meet a term of service in the country; these policies proved unpopular with regulators. In April 2015, the government also included nurses in the Emigration Check Required (ECR) category, citing corruption and nurse exploitation as a result of non-transparency in the recruitment process. The Emigration Clearance (EC) system, applied to workers going to 18 countries, requires clearance from the Protector of Emigrants office, which is situated in New Delhi. This regulatory process previously only applied to low-skilled domestic and construction workers, or those who lack a tenth grade (matriculation) certificate. This policy requires nurse recruitment be channeled through six state-related employment agencies (see Table 3) and nurses may only work on international contracts approved by government authorities.

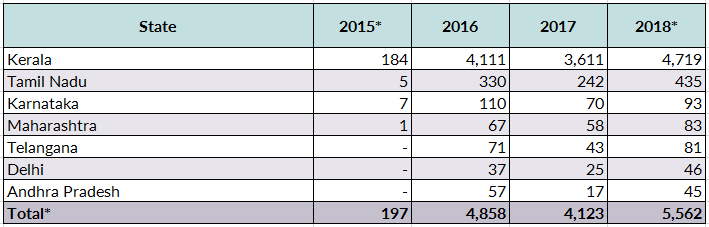

Imposition of the emigration clearance process on nurses represents a heavy regulatory hand. Rather than addressing the issue of corruption among migrant recruitment intermediaries, the state has chosen to constrain the mobility of nurses through a series of regulatory hurdles in the form of recruitment and emigration clearance, which has increased the cost of migration. After the imposition of this regulation, the numbers of ECR nurse migrants fell, though they have since increased (see Table 2). The majority (4,460) of these ECR nurses in 2018 headed to Saudi Arabia. This concentration in specific markets poses a threat if international relations or economic conditions shift.

Table 2. Emigration of Nurses by State under Emigration Check Required (ECR), May 2015-November 2018

Source: Government data obtained by the authors in 2018 through the Right to Information Act.

Nurses going through the emigration clearance stream must process their applications through six state-run agencies, five of which are in the south and one in the north.

Table 3. Indian State-Run Agencies through Which International Nurse Recruitment Is Allowed

Source: Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, office order dated September 9, 2016.

While one of the purposes of including nurses in the ECR category was to also regulate recruiting fees, fees charged by recruiting agents have not reduced noticeably, putting into question the whole rationale for this policy.

Beyond the imposition of bureaucratic requirements and other efforts to limit nurse migration, some policymakers are seeking more proactive ways of stemming departure. The state of Kerala, which is the source of most Indian nurses going abroad, in 2018 mandated that those working in private hospitals be paid a minimum wage of Rs. 20,000 a month (equivalent to US $282). This move can be seen as a way to begin to bridge the gap in wages that are one factor enticing nurses to seek overseas employment.

Monitoring Emigration

The government is also taking steps to centralize the Emigration Clearance process, with the Ministry of External Affairs in 2019 proposing legislation that would bring all intending emigrants—including students—under its purview. The draft bill, which would overhaul the 1983 Emigration Act, would also make the emigration clearance system far more streamlined and regulate recruitment intermediaries, who are currently outside the purview of the Emigration Act and are seen as the main source of exploitation for prospective nurse migrants.

Limited Policy Impact?

Overall, these various policy changes may have limited influence on health-worker emigration. Limiting the provision of NORI for U.S.-bound physicians and the ECR imposition on nurses suggest a more active government stance on health-worker migration. But this is being achieved through bureaucratic reform—not systematic change to the underlying employment context in the sending region that could make remaining in India a more desirable outcome for health-care workers.

The Indian government has made clear its view that medical tourism presents an economic opportunity. For example, the Ministry of Tourism website states: “India holds advantage as a medical tourism destination due to the following factors: Most of the doctors and surgeons at Indian hospitals are trained or have worked at some time in the leading medical institutions in the U.S., Europe, or other developed nations.” There is a certain irony in this, however, considering government efforts to restrict international mobility. While medical tourism is playing an increasingly important role in India, it not yet clear how this will intersect with the dynamics of health-care worker migration.

The Way Forward

Even as it is possible to track the migration of Indian health-care professionals through destination-country data, much remains unknown about the scope of this overall migration pattern. Domestic data on the migration of health workers are extremely fragmented, making it difficult to assess the exact nature and dimensions of this migration flow. What is certain, though, is that amid aging populations and health-care worker shortages in key OECD countries, the migration of Indian health-care professionals will continue.

As a result, policies need to be developed in India and destination countries that will protect the rights of professionals during recruitment and in the workplace, and allow them to fully utilize their skills. Barriers to credential recognition, workplace discrimination, professional deskilling, and austerity-informed restructuring in the health labor force are a constant challenge. Greater bilateral and global collaboration is needed to address them. As India maintains its leading position as a source for health-care workers to the world, monitoring and regulating emigration will be equally important as protecting the rights of Indian workers overseas.

Sources

Adkoli, B.V. 2006. Migration of Health Workers: Perspectives from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Regional Health Forum 10 (1): 49-58.

Anand, Sudhir and Victoria Fan. 2016. The Health Workforce in India. Human Resources for Health Observer Series No. 16, World Health Organization, Geneva. Available online.

Baker, Carl. 2019. NHS Staff from Overseas: Statistics. House of Commons Briefing Paper, No. 7783, July 8, 2019. Available online.

Brahmapurkar, Kishor, Parashramji Sanjay P. Zodpey, Yogesh D. Sabde, and Vaishali K. Brahmapurkar. 2018.The Need to Focus on Medical Education in Rural Districts of India. The National Medical Journal of India 31 (3): 164.

Chhapia, Hemali. 2019. China Gets More Indian Students than Britain. The Times of India. January 7, 2018. Available online.

Economic Times. 2019. UK Home Secretary Promises New Fast-Track Visa for Doctors from Countries Like India. The Economic Times, November 8, 2019. Available online.

Garner, Shelby L., Shelley F. Conroy, and Susan Gerding Bader. 2015. Nurse Migration from India: A Literature Review. International Journal of Nursing Studies 52 (12): 1879-90.

George, Gavin and Bruce Rhodes. 2017. Is There a Financial Incentive to Immigrate? Examining the Health Worker Salary Gap between India and Popular Destination Countries. Human Resources for Health 15 (74). Available online.

Global Health Observatory. 2019. Nursing and Midwifery Personnel. Updated March 14, 2019. Available online.

Hohn, Marcia D., James C. Witte, Justin P. Lowry, and José Ramón Fernández-Pena. 2016. Immigrants in Health Care: Keeping Americans Healthy through Care and Innovation. Fairfax, VA: George Mason University Institute for Immigration Research. Available online.

Humphries, Niamh, Ruairi Brugha, and Hannah McGee. 2012. Nurse Migration and Health Workforce Planning: Ireland as Illustrative of International Challenges. Health Policy 107 (1): 44-53.

Kaushik, Manas, Abhishek Jaiswal, Naseem Shah, and Ajay Mahal. 2008. High-End Physician Migration from India. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 86: 40-45. Available online.

Kumar, Raman and Ranabir Pal. 2018. India Achieves WHO Recommended Doctor Population Ratio: A Call for Paradigm Shift in Public Health Discourse! Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 7 (5): 841. Available online.

Medical Council of India. N.d. List of College Teaching MBBS. Accessed January 17, 2020. Available online.

Ministry of Health, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. 2019. Health Manpower in KSA. Updated July 10, 2019. Available online.

Ministry of Human Resource Development, Department of Higher Education, Government of India. 2019. Scholarships and Education Loan. Last updated January 22, 2019. Available online.

Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs, Government of India. 2015. F. No. 01-11012/10/2013-EP. April 8, 2015. Available online.

Mullan, Fitzhugh. 2006. Doctors for the World: Indian Physician Emigration. Health Affairs 25 (2): 380-93. Available online.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Statistics. N.d. Health Workforce Migration, Foreign-Trained Doctors by Country of Origin – Stock. Accessed January 16, 2020. Available online.

Potnuru, Basant. 2017. Aggregate Availability of Doctors in India: 2014-2030. Indian Journal of Public Health 61 (3): 182. Available online.

Rajan, S Irudaya, Varun Aggarwal, and Priyansha Singh. 2019. Draft Migration Bill 2019: The Missing Link. Economic and Political Weekly LIV (30): 19-22.

Rajan, S. Irudaya, Margaret Walton-Roberts, and Jolin Joseph. Forthcoming. Gender-Restricted Emigration and Repercussion: The Case of Nurse Emigration from India to the Gulf Countries. Economic and Political Weekly.

Rao, Krishna D. 2014. Situation Analysis of the Health Workforce in India, Human Resources Technical Paper 1. New Delhi: Public Health Foundation of India. Available online.

Rao, Mohan, Krishna D. Rao, AK Shiva Kumar, Mirai Chatterjee, and Thiagarajan Sundararaman. 2011. Human Resources for Health in India. The Lancet 377 (9765): 587-98.

Rao, Krishna D., Renu Shahrawat, and Aarushi Bhatnagar. 2016. Composition and Distribution of the Health Workforce in India: Estimates Based on Data from the National Sample Survey. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health 5 (2): 133.

Reddy, Sunita and Imrana Qadeer. 2010. Medical Tourism in India: Progress or Predicament? Economic and Political Weekly 45 (20): 69-75. Available online.

Scroll. 2018. After Months of Protests, Kerala Government Revises Nurses’ Minimum Monthly Salaries to Rs 20,000. Scroll, April 24, 2018. Available online.

Sharma, Anjali, Sanjay Zodpey, and Bipin Batra. 2016. India’s Foreign Medical Graduates: An Opportunity to Correct India’s Physician Shortage. Education for Health 29 (1): 42. Available online.

Shetty, Priya. 2010. Medical Tourism Booms in India, But at What Cost? The Lancet 376 (9742): 671-72.

Sood, Rita. 2008. Medical Education in India. Medical Teacher 30 (6): 585-91.

Times of India. 2016. 80 Percent Drop in Graduates Clearing MCI Screening Test. The Times of India, May 24, 2016. Available online.

---. 2017. Government Denies Visa Nod to Doctor Seeking to Do Research in U.S. The Times of India, July 18, 2017. Available online.

Thomas, Philomina. 2006.The International Migration of Indian Nurses. International Nursing Review 53 (4): 277-83.

Thompson, Maddy and Margaret Walton-Roberts. 2018. International Nurse Migration from India and the Philippines: The Challenge of Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals in Training, Orderly Migration, and Health-Care Worker Retention. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (14): 1-17.

Varghese, Joe, Anneline Blankenhorn, Prasanna Saligram, John Porter, and Kabir Sheikh. 2018. Setting the Agenda for Nurse Leadership in India: What Is Missing. International Journal for Equity in Health 17 (1): 98.

Walton‐Roberts, Margaret. 2012. Contextualizing the Global Nursing Care Chain: International Migration and the Status of Nursing in Kerala, India. Global Networks 12 (2): 175-94.

---. 2015. International Migration of Health Professionals and the Marketization and Privatization of Health Education in India: From Push–Pull to Global Political Economy. Social Science & Medicine 124: 374-82.

Walton-Roberts, Margaret, Vivien Runnels, S. Irudaya Rajan, Atul Sood, Sreelekha Nair, Philomina Thomas, Corinne Packer, Adrian MacKenzie, Gail Tomblin Murphy, Ronald Labonté, and Ivy Lynn Bourgeault. 2017. Causes, Consequences, and Policy Responses to the Migration of Health Workers: Key Findings from India. Human Resources for Health 15 (1): 28.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2017. A Dynamic Understanding of Health Worker Migration. WHO Brochure, Geneva. Available online.

---. 2017. From Brain Drain to Brain Gain: Migration of Medical Doctors from Kerala. New Delhi: WHO. Available online.