You are here

Haitians Flee a Nation Nearing Collapse

Haitians at a medical site in Jeremie, Haiti. (Photo: Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Benjamin Lewis/U.S. Navy)

In recent months, desperate Haitians have crowded at immigration centers in Port-au-Prince to obtain a passport. Tens of thousands have headed towards the United States, risking life and health to cross the Darien jungle between South and Central America or crowding onto rickety boats to cross the ocean. Many have taken similar journeys towards other Caribbean shores. And a growing number are moving across the island of Hispaniola to the Dominican Republic, where they face documented abuses and the near-constant risk of deportation.

All these scenes are increasingly common. They tell one story: People are leaving Haiti as if their lives depend on it.

This new wave of emigration adds to the long list of people who have left the country since a massive earthquake in 2010 and in the wake of violent riots that culminated in a political crisis in 2018. Challenges such as poverty, natural disasters, political crisis, and insecurity have historically driven Haitian migration, and have continued to do so in the aftermath of the July 7, 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse, which led to a power vacuum. Even before Moïse’s killing, about half the population lived in poverty. Dominican President Luis Abinader last year said Haiti was in the midst of a “low-intensity civil war,” underscoring the unprecedented nature of the country’s implosion.

Current migrants are distinct from the so-called boat people who sought humanitarian protection in the United States in recent decades, nor are they necessarily solely seeking better living conditions. They include Haitians with dual citizenship who had once chosen to raise their families in Haiti but now feel they have no choice but to leave. There are also those from the middle and upper classes who have lost hope of leading a normal life in their native land; their collective departure represents not only the movement of individuals but also a brain drain that could further erode the country’s prospects and a symbol of declining optimism for the future.

The United States is the most popular destination for Haitian migrants, although many are also going to Brazil, Canada, Chile, and the Dominican Republic, as well as other countries in the Caribbean, Europe, and Latin America. In recent years, many Haitians who moved to countries such as Brazil and Chile have migrated elsewhere for a second or third time as economic opportunities for Haitian migrants dried up. Because of the inherent challenges of leaving, only the most privileged have been able to afford to depart by plane, with most using land routes and a smaller number sea crossings.

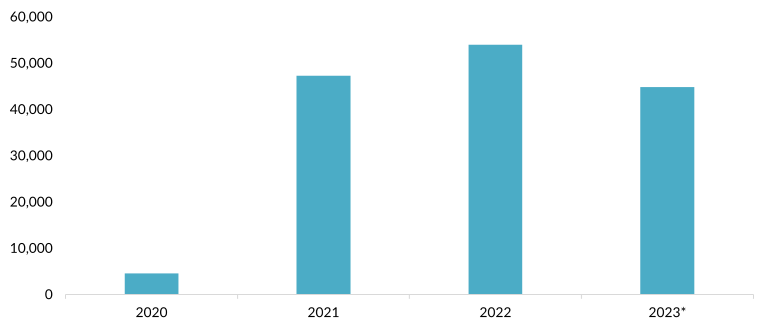

From October 2020 through May 2023, U.S. authorities encountered Haitians at the U.S. southwest border nearly 146,000 times (see Figure 1). From October 2022 through mid-June 2023, the U.S. Coast Guard interdicted more than 4,600 Haitian migrants at sea. As of mid-February, more than 5,000 Haitians arrived through a new humanitarian parole program that allows people in the United States to sponsor arrivals coming by plane, which has prompted the exceptional demand for Haitian passports (the program is also available to Cubans, Nicaraguans, and Venezuelans); more than 580,000 Haitian cases were pending as of May. Newcomers join a population of 697,000 Haitian immigrants in the United States as of 2021. As of this January, 107,000 Haitians held Temporary Protected Status (TPS), granting them U.S. work authorization and protection from deportation through August 2024, and 105,000 more were estimated to be eligible to apply.

Figure 1. U.S. Customs and Border Protection Encounters of Haitians at the U.S.-Mexico Border, FY 2020-23*

* Data for fiscal year (FY) 2023 are for the first eight months of the year, from October 1, 2022 through May 31, 2023.

Source: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), “Nationwide Encounters,” updated June 14, 2023, available online.

Often, destination countries have rejected Haitian arrivals and sought to deport them in large numbers. Since 2022, the Dominican Republic—which has a nearly century-long history of anxiety about Haitian immigrants—has been building a wall along much of the 244-mile (390-kilometer) border between the two countries. Last year, Dominican authorities deported more than 170,000 Haitians. From January 2021 to February 2022, the United States deported more than 20,000 people to Haiti, according to Human Rights Watch analysis, and in 2021 U.S. authorities’ clearing of a Del Rio, Texas, camp housing an estimated 15,000 Haitian migrants came to symbolize the government’s broader efforts to restrict irregular crossings. Countries including the Bahamas, Cuba, and Turks and Caicos have deported an additional 5,500 Haitians.

This article explores current migration from Haiti and prospects for the future, focusing on the primary displacement factors such as the deteriorating security situation, political climate, and economic crisis.

Gang Violence and Insecurity

Gang violence and insecurity are significant contributors to Haitians’ displacement. In April, more than 600 Haitians were killed as a result of gang violence and related incidents in Port-au-Prince, the capital, where gangs control about 80 percent of the territory. Kidnapping is also soaring; some families and communities have diverted their life savings to pay ransom to gang members. Victims of sexual violence, meanwhile, range from girls as young as 10 to the elderly. In October, gangs took control of the country's biggest fuel terminal, in a show of power that caused widespread disruptions and forced hospitals to close.

Gangs are widespread, control a large part of Haitian territory, have strong ties to the political and economic elite, and use more sophisticated guns than the police. Several high-profile journalists and activists have been killed. On a single day—July 8, 2022—gangs killed up to 95 people in the Port-au-Prince slum of Cité Soleil, including a 2-year-old. The police are weak, lacking officers and equipment, leaving the population at the gangs’ mercy. The only significant resistance gangs face is from a recent vigilante movement that started in April; fighting between the two sides could cause even more civilian deaths. The United States and Canada have levied economic sanctions on Haitian politicians and others alleged to be supporting gangs and contributing to instability, but some high-profile businesspeople and politicians have yet to face charges in Haiti.

More than 165,000 people had been internally displaced by gang violence in Haiti as of June, according to the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Many Haitians had to flee overnight; some returning to rural areas they had previously left to seek a better life in the capital. While the climate of violence and fear has forced many Haitians to flee, it has prevented others from working or leaving their homes. For example, in 2022, three women from the same family were killed and burned by gangs while going to church, and images of the crime further terrorized Haitian women, prompting many to restrict their movement.

Gang warfare has had ripple effects on virtually all aspects of life. Approximately 4.9 million Haitians—nearly half the country’s population—were food insecure as of this writing, and at times they cannot receive aid due to gang activities. This was the case after the earthquake that hit the country's south in 2021; gangs blocked access to the southern region by controlling Martissant, a Port-au-Prince neighborhood on the main road south. Halting a resurgent outbreak of cholera—which returned in October for the first time in three years—has been difficult in part because gangs have prevented health-care workers from accessing poor areas and made people afraid to visit hospitals. The situation is made worse by chronic underdevelopment. Nationwide, the average Haitian is expected to live only 63 years old, whereas in the Dominican Republic average life expectancy is 73 years.

Political Instability and Unrest

Gang rule seems likely to persist due to the absence of appropriate measures to tackle it effectively, as well as the prevailing governance crisis and collapse of numerous government institutions. Currently, the country has no functioning president, parliament, or other elected officials. It is ostensibly being run by a transitional government headed by acting Prime Minister Ariel Henry, whose succession to the presidency was never ratified by law; the Henry administration does not have popular support. No elections have occurred since 2016, and there is no prospect for elections and a return to democracy any time soon.

“Haiti is not governed nor administered," well-known lawyer and constitutionalist Monferrier Dorval warned hours before he was killed in August 2020. The warning typified concerns of educated Haitians bemoaning the dissolution of good governance and the rule of law.

What government does exist has been plagued by rampant corruption. Transparency International ranked Haiti 171st out of 180 countries in terms of public perceptions of corruption in its 2022 index, and many watched in recent years as a major corruption scandal linked to the oil-and-aid program PetroCaribe was met with impunity. These kinds of incidents have further discouraged many Haitians who aspire to play a role in the country's public administration and politics. Indeed, many Haitians have lost hope that the political class can solve the crisis, and have sought stability elsewhere. Studies have shown how corruption increases emigration intentions across countries, particularly among high-skilled migrants. While it is impossible to understand precisely how corruption has driven emigration, recent dynamics mirror the flight of thousands of middle- and upper-class Haitians who fled the Duvalier dictatorship in the 1950s and 1960s, during a period also marked by corruption.

Diminishing Economic Opportunities

Early waves of Haitian emigration tended to be driven by economic hardship. In the early 20th century, tens of thousands of Haitians moved to Cuba and the Dominican Republic, often to work on plantations and in other sectors. A century later, new economic struggles have again presented as a significant migration driver. In January, inflation reached a record 49.3 percent. The exchange rate between the Haitian gourde and the U.S. dollar more than doubled since 2018, from 65-to-1 to 139-to-1 in July. Due to Haiti's dependence on imported goods, the exchange rate is an indicator of affordability. Many landlords set rental prices in dollars, but Haitians often receive their salary in gourdes. Any increase in this exchange rate can therefore translate into lower purchasing power.

Officials have estimated that half the population lives below the poverty line of $3.65 per day; most people cannot sustain their lifestyle in these conditions. Successive years of negative economic growth mean fewer opportunities. The agricultural sector has mostly flatlined, and the manufacturing industry is struggling to stay afloat as social unrest threatens facilities and workers. Hotels and restaurants have been affected as nightlife has plummeted amid widespread security concerns. At the end of 2022, businesses began moving with their owners; several entrepreneurs relocated to the Dominican Republic, where they opened new businesses or restarted those they had in Haiti.

With meager local economic activity, money from abroad has become increasingly important for many households and the overall economy. The $4.2 billion in remittances sent to Haiti through official channels in 2021 accounted for one-fifth of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), according to the World Bank. These transfers represent a lifeline for many households and a reminder of opportunities outside the country, making clear to Haitians their best bet for making money and helping others may be if they leave Haiti.

Haitians Greeted with Harsh Reception

Not for the first time, many Haitian migrants are finding stiff barriers to movement. Many who fled have gone to the Dominican Republic, despite its history of animosity towards Haitian migrants and others with Haitian ancestry. Perhaps most memorably, the country in 2013 stripped Dominican citizenship from an estimated 210,000 people of Haitian descent who had been born in the country since 1929. As Haiti’s crisis has escalated, so too has the Dominican Republic’s apparent resolve at halting immigration. Recently, pregnant women and children have been expelled without their families, and at least 1,800 unaccompanied children were deported in 2022. In addition to the wall under construction, popular demonstrations in the Dominican capital, Santo Domingo, have rallied against Haitians’ presence. Still, many migrants have made clear that they would rather face this kind of backlash than the gang violence that has overtaken Haiti. There are no official data on the number of Haitians in the Dominican Republic, but estimates suggest there may be as many as 1 million.

Others have left the island of Hispaniola. However, many Haitians arriving in the United States and elsewhere are those who had previously migrated to Latin America in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake. Though they initially found jobs and some stability, Haitians in Brazil, Chile, and elsewhere in South America have encountered diminishing opportunities and difficulties settling in these first countries of destination amid economic turmoil, in some cases linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, and rising xenophobia. As the situation has worsened in Haiti, many have also felt a greater responsibility to help their loved ones in the homeland; while returning to Haiti is often not feasible, they have sought out more opportunities elsewhere so they can send back money.

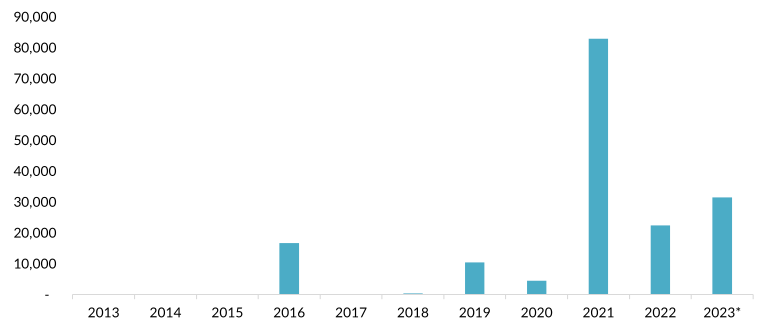

These Haitians moving for a second and third time are part of a larger group of migrants on the move from other countries in the Americas, including Cuba, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. Driven in part by domestic crises, the rapid post-pandemic U.S. economic recovery, perceptions that the Biden administration might welcome them more warmly, and other factors, many have looked towards the U.S.-Mexico border. For those coming from South America, this has often meant passage through the Darien Gap, a once-inaccessible stretch of jungle between Colombia and Panama that has become an increasingly popular migration route.

Figure 2. Haitians Crossing the Darien Gap, 2013-23*

* Data for 2023 are through May.

Source: Servicio Nacional de Fronteras (SENAFRONT), “Cuadro No. 001 Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: año 2010-2019,” accessed June 6, 2023, available online; SENAFRONT, “Cuadro No. 001 Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: año 2020,” accessed June 6, 2023, available online; SENAFRONT, “Cuadro No. 001 Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: año 2021,” accessed June 6, 2023, available online; SENAFRONT, “Cuadro No. 001 Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: año 2021,” accessed June 6, 2023, available online; SENAFRONT, “Cuadro No. 001 Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: año 2022,” accessed June 6, 2023, available online; SENAFRONT, “Cuadro No. 001 Tránsito irregular de extranjeros por la frontera con Colombia por región según orden de importancia: año 2023,” accessed July 3, 2023, available online.

Some aiming to reach Canada have crossed through the United States and towards Roxham Road, a rural, unofficial border crossing with New York State that had seen an uptick in unauthorized crossings before Canadian and U.S. officials updated their Safe Third Country Agreement in March to reduce the incentive for crossing there. At the same time, Canada also announced it would accept 15,000 new humanitarian migrants from Haiti and elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere. The U.S. humanitarian program launched in January offers the possibility for quick entry for some, although they will need to have U.S. sponsors who can provide financial and other assistance and will also need to fly into the country. Meanwhile, some of the thousands of Haitians blocked from entering the United States have formed small but vibrant communities in Mexican border towns such as Tijuana.

More Migration Is in Sight

As the multifaceted crisis in Haiti persists, there appear to be no concrete plans by the international community to address the situation. Henry has pleaded for an international military intervention—particularly one led by Canada or the United States—but it has not come to pass. In February, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced his country would send naval vessels to the island but stopped short of a larger mission. Citing the rising killings and kidnappings, the United Nations in March called for the deployment of an international specialized support force.

In the absence of any signs of improvement, more Haitians will likely continue to emigrate, exacerbating the brain drain that is one of the country's challenges. For instance, more professionals are needed in the health sector, yet doctors and other medical professionals are leaving the country. Living and raising children in Haiti means sacrificing numerous opportunities for their future. According to a 2020 World Bank study, a Haitian child will be only 45 percent as productive as an adult as they would be if they had had complete education and health care.

What remains of the Haitian government meanwhile seems weak, mired in corruption, and lacking an innovative strategy or budget to signal it can protect Haitians and make the country prosperous. Politicians and civil society leaders have so far proven unable to solve the crisis, and international assistance is either feeble or nonexistent.

On the other hand, emigration appears more accessible than ever. Plans are regularly discussed openly on social media, creating virtual communities where Haitians can access information like never before, including about how to navigate the migration process, which routes to take, and other aspects of travel. As migrants have settled in new destinations, they have eased the path for those who follow. Despite the barriers erected by the Dominican Republic, the United States, and elsewhere, more destinations seem within reach, and the easing of COVID-19-era border restrictions has allowed for greater migration than any point since 2020. Just a few years ago, for instance, it would have been unthinkable for migrants in South America to trek across the Darien jungle, but the path is now taken by an average of about 1,000 people per day.

In sum, Haiti faces a multifaceted crisis involving political instability, gang violence, a spiraling economy, and an unfolding humanitarian catastrophe. The situation is dire, and current migration will likely exacerbate the country’s brain drain, depriving it of human resources, capital, and other supplies to rebuild. Despite the obstacles migrants face—including abuse and exploitation as well as risk of deportation—many have shown they do not believe the solutions to their problems are in Haiti. Without improvement, it is likely that Haitians will continue to emigrate, fleeing violence and looking to build a better life.

Sources

Auer, Daniel, Friederike Römer, and Jasper Tjaden. 2020. Corruption and the Desire to Leave: Quasi-Experimental Evidence on Corruption as a Driver of Emigration Intentions. IZA Journal of Development and Migration 11 (1). Available online.

Bishop, Marlon and Tatiana Fernandez. 2017. 80 Years On, Dominicans and Haitians Revisit Painful Memories of Parsley Massacre. National Public Radio, October 7, 2017. Available online.

Cooray, Arusha and Friedrich Schneider. 2016. Does Corruption Promote Emigration? An Empirical Examination. Journal of Population Economics 29: 293–310. Available online.

Dupain, Etant and Eliza Mackintosh. 2022. Haiti: Gang Violence Leaves Nearly 200 Dead in a Month. CNN, May 31, 2022. Available online.

Haiti Libre. 2023. Haiti - FLASH : Annual Inflation Continues to Rise to 49.3% (January 2023). Haiti Libre, March 17, 2023. Available online.

Hu, Caitlin and Etant Dupain. 2022. Exclusive: Dominican Republic Expelled Hundreds of Children to Haiti without Their Families This Year. CNN, November 22, 2022. Available online.

Human Rights Watch (HRW). 2022. Haiti: Wave of Violence Deepens Crisis. July 22, 2022. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2022. Gang Violence Displaces 165,000 in Haiti, Hinders Aid Efforts. Press release, June 8, 2023. Available online.

Phillips, Tom. 2023. “It's Hell”: Vigilantes Take to Haiti's Streets in Bloody Reprisals Against Gangs. The Guardian, April 30, 2023. Available online.

Selee, Andrew et al. 2023. In a Dramatic Shift, the Americas Have Become a Leading Migration Destination. Migration Information Source, April 11, 2023. Available online.

Sullivan, Eileen and Steve Fisher. 2023. At the End of a Hard Journey, Migrants Face Another: Navigating Bureaucracy. The New York Times, March 10, 2023. Available online.

UN News. 2023. Haiti: International Support Needed Now to Stop Spiralling Gang Violence. UN News, May 9, 2023. Available online.

UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). 2022. Sexual Violence in Port-au-Prince: A Weapon Used by Gangs to Instill Fear. New York: OHCHR. Available online.

UNICEF. 2022. Increase in Violence and Resurgence of Cholera in Haiti May Leave More than 2.4 Million Children Unable to Return to School – UNICEF. Press release, October 11, 2022. Available online.

U.S. Coast Guard. 2023. Coast Guard Transfers 20 People to Bahamas. Press release, June 23, 2023. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). 2023. CBP Releases February 2023 Monthly Operational Update. Press release, March 15, 2023. Available online.