You are here

Aging Societies Rely on Immigrant Health-Care Workers, Posing Challenges for Origin Countries

A health worker from the Philippines. (Photo: IOM/Angelo Jacinto)

The world is short on health-care workers. In 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) predicted a global shortfall of 10 million health workers of all types by 2030. In 2020, the global health workforce numbered 65 million, according to the WHO’s National Health Workforce Accounts, yet these workers are no match for the demand. As the population in high-income countries gets older and lives longer, and as institutions fail to train enough new workers, the gap between demand and supply has remained. People are also exiting the health-care workforce, due to factors including aging, insufficient educational spaces, and worker burnout; physicians and nurses are retiring without a ready supply of replacements. This was a problem prior to the COVID-19 pandemic but has persisted since the global public-health crisis arrived. The American Medical Association (AMA) stated that two in five U.S. physicians surveyed in 2022 were planning to leave the profession by 2027.

In This Article

When unable to source staff at home, wealthy countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and Saudi Arabia tend to turn abroad. The AMA, for instance, identifies better legal pathways for international medical graduates as the first way to relieve shortages, while Germany’s Triple Win program is designed to recruit thousands of foreign-born nurses. The number of migrant doctors working in mostly high-income countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) increased by 50 percent from 2006 to 2016, to nearly 500,000, while the number of migrant nurses increased by 20 percent from 2011 to 2016, to nearly 550,000. In 2020, more than 12 percent of all nurses globally were working in a country other than that of their birth, according to the WHO. In the United States, one-quarter of practicing physicians were trained abroad as of this writing, according to the AMA.

This trend has a mix of impacts for health-care workers’ countries of origin. While emigration can advance individuals’ careers and drive economic development through the money workers send back, countries’ domestic health-care workforces may become depleted. In places such as the Philippines, training schemes have shifted to suit the needs of international markets rather than local conditions.

This article examines the trends in international migration among health-care workers. It focuses on major countries of destination and origin, factors driving migration, and global efforts to regulate the movement and prevent shortages in source countries.

Box 1. Definitions

Health-care workers: An umbrella term that usually refers to anyone working as a trained health-care professional, including physicians, nurses, dentists, and pharmacists. Some researchers use the term when referring to more than one profession but not all, such as physicians and nurses. In this article this term does not refer to workers with lower levels of education, such as orderlies, or those who work in health-care administration.

Foreign-born health workers: Any health-care worker who is working in a country other than where they were born, when discussing the country of employment. They may have immigrated before or after being trained as a health worker.

Foreign-trained health workers: Health-care workers who migrated after receiving their first professional health degree in the country of their birth, indicating a loss of investment for their country of origin.

Top Sending and Receiving Countries

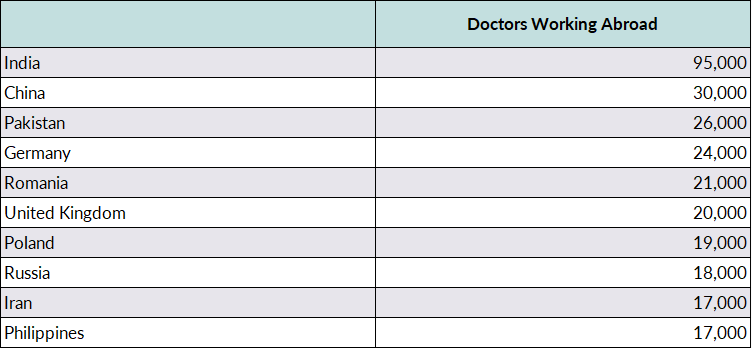

Relying on foreign-born and foreign-trained health workers is not a new phenomenon. Publicly available data are not comprehensive, but in recent decades the top source countries for physicians have included India, China, Pakistan, and Germany, among other high- and low-income countries, indicating that there are unique conditions surrounding medical migration (see Table 1). India is traditionally the top source country by far, however countries in sub-Saharan Africa and the Caribbean demonstrate high rates of physician migration, which has a disproportionate impact given the countries’ smaller overall populations. In 2020, the OECD reported that in some African and Latin American countries, more than 50 percent of native-born physicians emigrated. For instance, physician emigration rates were 77 percent in Liberia and 54 percent in Guyana.

Table 1. Top Origin Countries of Foreign-Born Doctors, 2015-16

Note: Table shows number of foreign-born doctors in countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Source: Stefano Scarpetta, Jean-Christophe Dumont, and Karolina Socha-Dietrich, “Contribution of Migrant Doctors and Nurses to Tackling COVID-19 Crisis in OECD Countries,” OECD, May 13, 2020, available online.

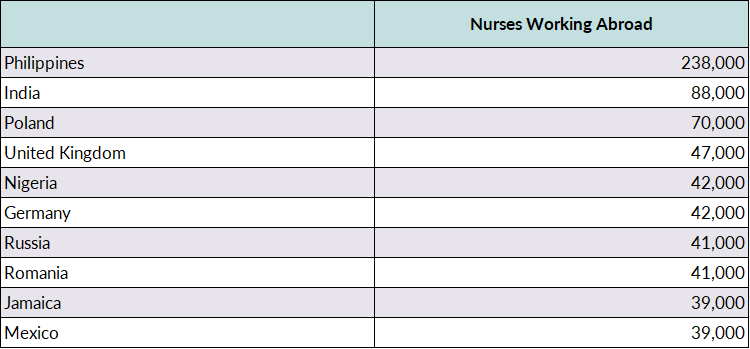

Although there are more migrant nurses working internationally than physicians, they comprise a smaller percentage of the overall number of nurses worldwide. Leading source countries for nurses include the Philippines, India, and Poland. In 20-plus countries, mostly in Latin America and Africa, more than 50 percent of all native-born nurses have emigrated. The Philippines has long been the source for the most migrant nurses. In 2021, the Filipino Department of Health estimated that 316,000 licensed nurses (51 percent of all licensed ones in the country) had migrated overseas, many destined for the United States. In 2021, Filipino nurses accounted for 27 percent of the 546,000 foreign-born registered nurses in the United States. India (7 percent) and Mexico and Jamaica (5 percent each) were a distant second, third, and fourth.

Table 2. Top Origin Countries of Foreign-Born Nurses, 2015-16

Note: Table shows number of foreign-born nurses working in OECD countries.

Source: Scarpetta, Dumont, and Socha-Dietrich, “Contribution of Migrant Doctors and Nurses to Tackling COVID-19 Crisis in OECD Countries.”

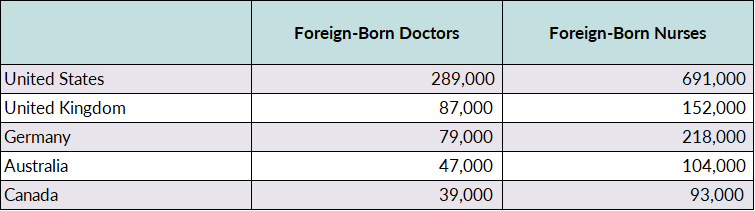

The top destination countries have traditionally been the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and Saudi Arabia. Newer destinations are France, Germany, Sweden, and Switzerland. The United States hosts around 40 percent of the total emigrant physician population, although there has been a slight decline in recent decades.

Table 3. Immigrant Doctors and Nurses in Select Destination Countries, 2015-16

Source: Scarpetta, Dumont, and Socha-Dietrich, “Contribution of Migrant Doctors and Nurses to Tackling COVID-19 Crisis in OECD Countries.”

As a non-OECD nation, Saudi Arabia is an outlier among destination countries for medical migrants, but it has played a key role in this phenomenon. With the oil boom in the 1970s, the Saudi government spent massive amounts of financial capital to build infrastructure, including health-care infrastructure, creating a demand for workers. Due to religious and cultural norms, the country has historically relied on non-Saudi workers in many health fields, especially nursing, which has been considered an inappropriate profession for Saudi women. In 2001, for instance, approximately 80 percent of nurses working in Saudi Arabia were foreign born.

However, in an effort to combat unemployment among Saudis, the government has embarked on a Saudization plan to replace foreign workers with natives. While still a destination country, recent statistics show Saudi Arabia is less reliant on foreign health-care workers than in the past. In 2021, the Saudi Ministry of Health stated that about half the country’s physicians and dentists were non-Saudi, as were 37 percent of nurses. This is a reduction from the beginning of the millennium and from 2012, when rates were 75 percent and 64 percent, respectively. Foreign-born physicians typically come from Muslim countries in the Middle East such as Egypt and Jordan, as well as India and Pakistan, while nurses tend to be from the Philippines and India.

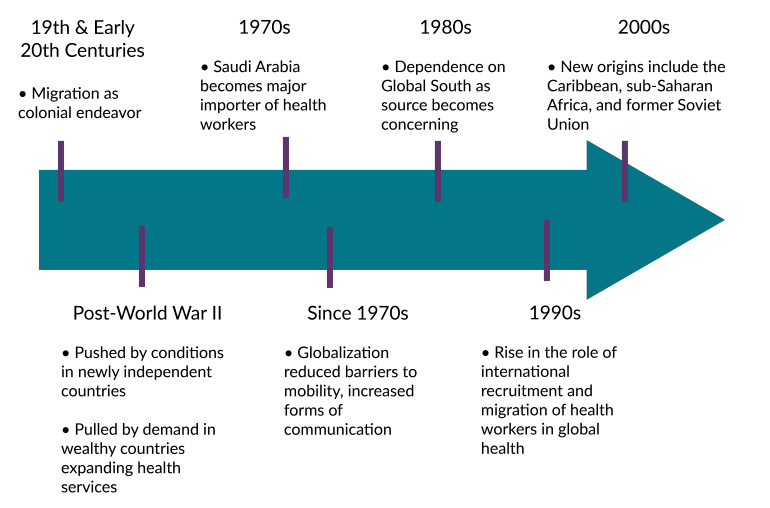

Health workers are motivated to migrate for the same reasons as other people: a desire to improve financial conditions for themselves and their families; increase personal or professional development; and escape harsh social, economic, or political environments, which often impact health care; among other reasons. Due to their specialized training, health-care workers often have many opportunities abroad. In fact, the increased ability to migrate can incentivize individuals to choose a career in the health industry. The choice of destination can be affected by factors such as a shared language or history, personal networks, and employer or licensing body recognition of training and educational credentials. Migration is rarely a linear experience, and it is not unusual for migrant health-care workers to replace other foreign-born workers or proceed through jobs in different countries to eventually reach their goal, which is often a position in the United States or the United Kingdom. Dynamics have also changed over time, depending on global demand, supply, and other factors (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Timeline of Health Worker Migration Trends

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) rendering of author’s creation.

Trends will differ by country. Physicians and nurses from sub-Saharan Africa have indicated their key push factors are lack of educational or training opportunities in the origin country, political strife, and family reunification. Meanwhile those from Eastern Europe tend to list social status, negative public perception of their field, and low government investment in health care as reasons for leaving.

Economic Factors

Economic factors often undergird many other drivers. The reasons health-care-worker migrants often cite for selecting their vocation include needing to earn and save money for better housing, dowries, and children’s education. In some low- and middle-income countries, individuals choose medical professions for economic mobility, which can lead to a surplus in the domestic health-care system and the necessity to migrate to find employment.

Professional Development

Health-care-worker migrants at all income levels often seek personal and professional development through additional education or specialized training, including the opportunity to learn or practice with new technologies and specialties. Migrating health-care workers report often feeling demoralized by the lack of continuing education or opportunities for career advancement in their place of origin. In countries such as Ghana and Nigeria, for instance, physicians are expected to emigrate to further their training.

Work Environment

Many health-care workers emigrate to leave poor working conditions. The work environment for health care can reflect a country’s broader social, economic, and political climate, and depends on factors including funding for the sector, organizational culture and structure, and individual safety. Lack of supplies, medicine, equipment, and staff create unsatisfactory work environments that push workers to other countries or out of the profession, leading to more staff shortages. Globally, nurses in particular experience shortages in all areas and often quote destination countries’ lower nurse-to-patient ratio as a pull factor.

Demand Abroad

These factors would be immaterial without the demand for health-care workers in wealthy countries. While staff shortages in sending countries create poor working conditions and push workers out, staff shortages in destination countries create landing places. The current global workforce is aging out and burning out and is not being adequately replaced. As shortages in destination countries arise, their health-care systems seek to address immediate concerns and often fall short in long-term planning, including by training enough new workers. In many countries, the training and clinical sides of health care are housed under different government ministries, leading to miscommunication and misunderstanding of needs and trends. Additionally, while some countries can both afford and recruit domestic health-care workers, others struggle with one or both elements.

A key problem is the training bottleneck in OECD countries, many of which regulate the number of clinical students admitted to educational programs to ensure programs have an institutional clinical partner with capacity to train students. The irony is that while native-born students are being turned away from education programs due to lack of space—the United Kingdom had around 21,000 applicants for 6,500 seats in medical programs in 2018—countries must then rely on foreign-educated workers to meet their clinical needs. On the other hand, Europe’s Bologna Process to synchronize higher education standards across the continent decreased the capacity for training nurses by as much as two-thirds in Czechia (also known as the Czech Republic).

Country Similarities

Postcolonial connections and proximity between countries affect migration patterns. The UK Parliament reported that in 2022 approximately 17 percent of National Health Service (NHS) workers came from other countries, mostly those with a history of UK ties. Nine of the top 20 origin countries were in the European Union, of which the United Kingdom was a member until 2020. An additional nine—including India, the top source country—were former colonies. Furthermore, the United States has become a popular destination for medical migrants from the Caribbean, a region with which it shares a language (for many countries) and a close proximity, making it easy for individuals to return for visits. These patterns reflect similarities between countries’ medical training and language, as well as ease of travel.

Migration Pathways and Recruitment Firms

To entice foreign health workers, destination countries may relax immigration regulations or provide specialist entry routes. The United States has special visas for migrant nurses and physicians, and Japan has trade agreements with Indonesia and the Philippines to accomplish similar ends. During the initial COVID-19 surge, many countries offered temporary or restricted licenses, fast-tracked recognition of foreign qualifications, or eased border closures for certain workers in order to safeguard their populations.

Even when governments have special pathways, however, navigating immigration processes is complicated. Consequently, many health organizations in destination countries use recruitment firms, which can be more cost effective, lead to quicker paperwork processing, and vet applicants according to individual hospital needs. Recruitment firms also serve as sales representatives for destination countries, hyping benefits that hospitals offer to be competitive, such as free travel, subsidized or free housing, tax-free salaries, and opportunities to improve medical training.

Private recruitment firms are not strictly regulated and, at times, may exploit international medical graduates by offering fictitious placements, deceptive salaries and benefits, or high fees. These companies receive finders’ fees from destination organizations but often make additional money by charging migrants for necessary services such as specialized training and processing paperwork.

Role of the WHO and Other Global Bodies

While local shortages will ebb and flow, globally the trend has been towards unevenly distributed shortages, reflecting larger global inequalities and often resulting in brain drain. As previously stated, many sub-Saharan African countries have high health-care vacancy rates due to extreme levels of emigration. As of 2010, three times as many Caribbean nurses were working in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States as in English-speaking Caribbean countries.

These shortages are felt in clinics and in health-care education, creating a trickle-down deficit. Fewer practicing professionals means fewer individuals free to move into teaching roles, meaning less capacity for new students. Furthermore, in clinical settings, overburdened clinical supervisors do not have time to devote to both patients and students, resulting in inferior training. Finally, the best candidates for moving into educational roles due to experience and training tend to find employment abroad, leaving a domestic vacuum in experienced practitioners.

The dilemma has been the most visible problem in global health-care migration. Leaders of low-income source countries have accused destination countries of “robbing,” “poaching,” and “raiding” their health services. Some argue that recruiting countries’ human resources without compensation is unethical and akin to colonial theft of natural resources.

The WHO’s 2010 Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel seeks to manage the situation, as do policies of the International Council of Nurses (ICN), a federation of national groups. Integral to the WHO’s code is its recognition of an individual’s right to migrate, which it maintains can be beneficial. But it discourages actively recruiting from developing countries “facing critical shortages of health workers” and encourages all Member States to create sustainable health workforces through “planning, education and training, and retention strategies” that would limit their need to recruit foreign workers. Unfortunately, the code is neither monitored nor enforced.

Managed Migration

Still, several countries are turning to different ways to manage migration. Nations including the United Kingdom have enacted policies for ethically recruiting international health-care workers. The European Commission has also stated concerns that relying on immigrant workers may not form a sustainable public-health strategy.

A number of Caribbean countries have developed the Managed Migration Program that organizes both training and movement of nurses around the region, to mitigate the negative impacts of emigration and maintain needed services. Whether it has been successful or sustainable is debatable.

Other countries have entered into bilateral agreements, as suggested by the WHO’s Code of Practice, to limit the need for recruitment firms, shift migration expenses to employers, and allow origin countries to negotiate benefits to their people. A Cuba-South Africa agreement, for instance, sends Cuban physicians and educators to South Africa in exchange for South African students enrolling at Cuba’s Latin American School of Medicine. Germany, planning for an estimated shortfall of 150,000 nurses by 2025, has developed the Triple Win program with countries including Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Philippines, and Tunisia. This program attempts to alleviate Germany’s shortage by employing nurses from countries with a nursing surplus, who can then provide remittances that boost their origin countries’ economies. By January 2022, 3,500 nurses had started working and an additional 1,400 had been placed.

Remittances are the primary benefit for source countries, yet attitudes towards migration depend on factors such as their population, the number of health-care workers, and the general well-being of the health-care system. While funds sent home by migrants can boost source-country economies, they are not often reinvested into the health-care system and do not offset expenses lost in training workers for foreign employment. Still, some countries capitalize on promoting emigration and have created what can be considered health-care worker export programs. The Philippines has long been the leader in this area for nurses, followed by India (specifically the southwestern region of Kerala), China, and some former Soviet states. In these cases, remittances can become a major source of national income. Filipino Nurses United, an advocacy group, reported that in 2021 Filipino nurses abroad remitted U.S. $8 billion, or about 2 percent of the Philippines’ gross domestic product (GDP). China has underinvested in its health-care system and does not have enough vacancies to employ all its trained nurses, leading many to migrate. However, the Chinese government often charges between 10 percent to 15 percent of a nurse’s annual salary to arrange a foreign work contract.

There is an underlying assumption that upon return, medical migrants will enrich the local health-care system with newfound training and techniques. Migrants who plan to return and work before retiring will often maintain a license to practice in their origin country, but it is doubtful that this benefits the health system. Often, new skills and knowledge do not match local conditions. Return migrants may not be welcomed in their home systems or have problems reintegrating, while others choose not to practice.

One of the main detriments for source countries is little to no return on investment for the cost of educating and training health workers, especially for countries that fund this training. Nine sub-Saharan African countries lost almost U.S. $2.2 billion in investments made to educate physicians, according to a study published in 2011, while the United Kingdom and United States saved $2.7 billion and $846 million, respectively. Researchers estimated in 2006 that the Kenyan government was losing $518,000 and $339,000 for each emigrating doctor and nurse, respectively.

One reason for the mismatch is that medical workers training to go abroad often focus on global health trends that do not reflect local needs. In the Philippines, for example, the rapid rise of migration-focused nursing schools has led to inconsistent training standards and declining board exam pass rates. Additionally, with such a large supply of nurses, the Filipino health system can afford to force graduates to work for little or no pay to gain experience before finding paid work abroad.

Source countries do have some recourse to create barriers to health workers’ emigration. Bonding schemes such as those used by Ghana, India, and Zimbabwe require health professionals to work for the government for a specified period of time or buy back the bond before they are allowed to work overseas. However, these schemes are difficult to enforce and often prove ineffective.

The full impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on global health-care systems remains unknown, but it has likely exacerbated the need for health workers. In 2022, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) reported health-care workers’ fatality rates were lower than those of the general population, but the sector was clearly wounded by the pandemic. The WHO estimated in October 2021 that about 115,000 health-care workers globally—and potentially as many as 180,000—died due to COVID-19, and the toll has surely increased since then.

The pandemic also had other long-lasting effects on global health workers, primarily overtopped workload and fatigue. Long-term psychological stress often leads to burnout and was compounded by a constant need for updates about new coronavirus variants. Workers responsible for COVID-19 patients are more likely to have depression, anxiety, and other forms of mental distress. This burnout has likely led to reduced work hours and early retirement for many. At a time when the health industry needed more workers, COVID-19 disrupted recruitment and retention and led to higher rates of turnover.

The pandemic underscored the gaping vulnerabilities that remain in the global health-care system. As populations in OECD countries age, they create an increasing health-care deficit. For now, they have come to rely heavily on foreign-trained health professionals, and this reliance will only increase unless health education is reformed to match future needs. Continued international recruitment will lead to ripple effects across global health systems.

Sources

Adovor, E., M. Czaika, F. Docquier, and Y. Moullan. 2021. Medical Brain Drain: How Many, Where and Why? Journal of Health Economics 76: 102409. Available online.

Baker, Carl. 2022. NHS Staff from Overseas: Statistics. London: The House of Commons Library. Available online.

Berg, Sara. 2023. Reduce Physician Burnout Now - or Face Rising Doctor Shortages. American Medical Association (AMA), September 27, 2023. Available online.

Buchan, James, Howard Catton, and Franklin A. Shaffer. 2022. Sustain and Retain in 2022 and Beyond: The Global Nursing Workforce and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Philadelphia: International Center on Nurse Migration. Available online.

Dinkin, Paul, et al. 2022. Care for the Caretakers: Building the Global Public Health Workforce. McKinsey & Company, July 26, 2022. Available online.

International Council of Nurses (ICN). 2021. ICN Says 115,000 Healthcare Worker Deaths from COVID-19 Exposes Collective Failure of Leaders to Protect Global Workforce. Press release, October 21, 2021. Available online.

Kirigia, Joses Muthuri, Akpa Raphael Gbary, Lenity Kainyu Muthuri, Jennifer Nyoni, and Anthony Seddoh. 2006. The Cost of Health Professionals' Brain Drain in Kenya. BMC Health Services Research 6 (1): 1-10. Available online.

Scarpetta, Stefano, Jean-Christophe Dumont, and Karolina Socha-Dietrich. 2020. Contribution of Migrant Doctors and Nurses to Tackling COVID-19 Crisis in OECD Countries. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), May 13, 2020. Available online.

World Health Organization (WHO). 2017. Health Employment and Economic Growth: An Evidence Base. Geneva: WHO. Available online.

---. 2021. Health and Care Worker Deaths during COVID-19. October 20, 2021. Available online.