You are here

India and Bangladesh Swap Territory, Citizens in Landmark Enclave Exchange

Two residents stand on either side of an enclave border. The water pump on the right is in India, while the house it serves is in a Bangladeshi enclave. (Photo: Hosna J. Shewly)

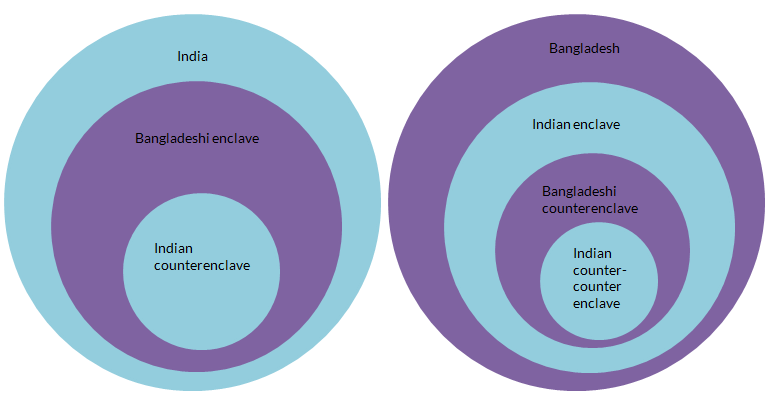

India and Bangladesh formally exchanged 162 enclaves on August 1, 2015, ending a centuries-old territorial anomaly and completing a process of land and population exchange that began in the 1950s. An enclave is the fragmented territory of one sovereign power located inside another sovereign territory. Following decolonization from the British Empire in 1947, both India and East Pakistan (later independent Bangladesh) retained enclaves totalling about 119 square kilometers within the other’s newly demarcated boundaries. In practice, this led to small populations of Indian citizens living in territory completely surrounded by Bangladesh, and vice versa. In a further territorial complication, a number of enclaves also hosted counterenclaves within their boundaries—in essence, a pocket of Indian land, surrounded by Bangladeshi territory, situated within India proper. There was even one case of an Indian counter-counterenclave (see Figure 1).

By the time of the exchange, there were an estimated 53,000 enclave residents in total, about 38,000 Indians in Bangladesh and 15,000 Bangladeshis in India. Over time, each country occasionally demanded full access to its enclaves on the other’s territory, but was unwilling to allow reciprocal access in turn. As a result, neither country made a serious attempt to extend governance or develop infrastructure in the enclaves locked in one another’s territory, leaving the residents largely neglected, and often the victims of bilateral antagonism.

Box 1. Enclave Exchange by the Numbers

Bangladeshi Enclaves

- 51 Bangladeshi enclaves in India became Indian territory, a total area of 7,110 acres

- 14,863 residents remained in India and became Indian citizens

Indian Enclaves

- 111 Indian enclaves in Bangladesh became Bangladeshi territory, a total area of 17,161 acres

- 989 residents resettled to India

- 37,532 residents remained in Bangladesh and became Bangladeshi citizens

Sources: Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), “Exchange of enclaves between India and Bangladesh,” (press release, November 20, 2015); MEA, India and Bangladesh Land Boundary Agreement (New Delhi: MEA, n.d.).

Trapped in a vicious catch—enclave residents needed a visa to cross the host country to reach their mainland, but needed to go to a consulate in the mainland to get a visa—residents could neither enter the host country or their mainland legally. Without identity documents, or the means to acquire them, enclave dwellers have lived for decades in virtual statelessness, and without basic educational, administrative, security, health, or postal services.

Over the decades, several initiatives to exchange the enclaves were proposed but remained unsuccessful due to domestic opposition and difficult bilateral relations. With the election of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in India in 2014 and the advent of a policy of closer cooperation with Bangladesh, efforts at resolving the enclave conundrum accelerated. As part of the final deal, India and Bangladesh agreed to surrender their territory and allow the residents to choose their country of citizenship.

In this period of transition from statelessness to citizenship, this article highlights the origin and long existence of the enclaves, difficulties of life in the enclaves in the last 68 years, and the long process of exchange. Based in part on the author’s PhD research and experience living on either side of an enclave border, this article explores the importance of national identity and belonging in residents’ citizenship decisions, as well as complications over land ownership and resettlement.

Figure 1. Enclaves in India and Bangladesh

Source: Adapted from Evgeny Vinokurov, A Theory of Enclaves (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2007).

The Enclaves’ 300-Year History

A great majority of the world’s enclaves were located in a small section of the India-Bangladesh borderland, in the former princely state of Cooch Behar (now the name of a district in the Indian state of West Bengal). Before the exchange, there were about 223 enclaves, 32 counterenclaves, and one counter-counterenclave in total around the world. Enclaves can be found in Western Europe—notably the Baarle enclaves in Belgium and the Netherlands—the former Soviet Union, and Asia. And in Morocco, the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla form the European Union’s only land borders with Africa.

The origin of the Indian and Bangladeshi enclaves dates to the 18th century, the outcome of war and peace treaties between rulers in Bengal and Cooch Behar. In ancient India, north Bengal proved a strategic location as a gateway to rest of the Bengal, and a frontier zone between Hindu, Muslim, and Buddhist kingdoms. While local legend has it the enclaves derived from a chess match between the Maharaja of Cooch Behar and a Mughal commander with villages as wager, they were in fact the result of a series of peace treaties signed from 1711-13 between the feudal Kingdom of Cooch Behar and the Mughal Empire. Having conquered a wide swath of Cooch Behar, the Mughals were unable to roust a number of Cooch Behar chieftains in areas surrounded by Mughal territory and the lands they held remained part of Cooch Behar. At the same time, a number of Mughal soldiers controlled estates within Cooch Behar, collecting taxes and ruling over the locals, and those districts became Mughal enclaves. The creation of the enclaves had little impact on everyday life as Cooch Behar was nominally a tributary state to the Mughal Empire. Over 300 years, the enclaves survived successive changes of sovereignty as the British replaced the Mughals, decolonization created independent India and Pakistan, and Bangladesh gained independence from Pakistan in 1971.

Figure 2. Former Enclaves of India and Bangladesh

Source: Map prepared by Dr. Rajib Haq.

Decolonization created ambiguity over the enclaves’ future in postpartition India, however. In 1947, partition procedures restricted independence for the princely states, including Cooch Behar, instead providing the option to choose whether to join India or Pakistan. Cooch Behar, one of the last to decide its preferred nation-state, signed the Cooch Behar Merger Agreement with India in August 1949. Since there were no specific regulations governing the enclaves, they received international status as either sovereign Indian or Pakistani territory following Cooch Behar’s merger with India. Within a period of 36 days in 1947, the British divided 80 million people and 175,000 square miles of land, which had been joined together in a variety of ways for about 1,000 years. The hasty and ambitious process of demarcating the almost 4,000-kilometer Bengal border ignored many issues, including resolving access to the enclaves.

The only initiative to link the enclaves with their mainlands was made under the 1950 agreement that provided access to government officials to enter the enclaves belonging to their side. But the agreement was never implemented due to its complicated procedures and hostile India-Pakistan relations. Crucially, however, enclave residents could move with a certain degree of freedom until the introduction of strict passport/visa and border controls in 1952. From then on, both India and Pakistan/Bangladesh ignored the needs of enclave residents, who were gradually isolated from state provisions due to physical distance from the mainland and political difficulties in securing government access. Neither side was sincerely willing to exercise sovereignty over its enclaves nor was the true human scale of the enclave problem fully grasped.

Life in the Enclaves

Life in the enclaves was particularly difficult after 1952. Many families had lived within the enclaves for generations, surviving on what they could farm or harvest from the land. But the advent of new national identities and border controls in the 1950s created new challenges to their survival. Critical services such as health centers, police stations, and schools were not built within. There were no mechanisms to regulate violent crimes, including rape and murder, in the enclaves as residents were excluded from state judicial systems. In addition, residents were often the victims of social exploitation by political elites, gangs, and mainland neighbors.

As India and Bangladesh began to develop the region, infrastructure projects such as roads and electrical supply would end at the boundaries of the enclaves. As India established border infrastructure including fences and checkposts in most places along the Bengal border to prevent irregular movement from Bangladesh, these measures also affected enclave dwellers’ mobility. It became necessary for residents to illegally enter the surrounding country to fulfill basic needs and for their economic survival (to access local shops to buy and sell goods, for instance), often becoming victims of sovereignty mechanisms and subject to prosecution as illegal intruders. More than 75 percent of the residents of Bangladeshi enclaves in India have spent time in prison after being arrested for entering Indian territory without valid travel documents.

For years, the India-Bangladesh Enclave Exchange Coordination Committee (IBEECC), a civil-society organization, conducted nonviolent activities including hunger strikes and peaceful rallies in India and Bangladesh to raise awareness among policymakers and the population of the suffering and dangers of enclave living, and to advocate for an early exchange of the enclaves.

The Long Road to Exchange

Securing state control of enclave territory through exchange has always been politically sensitive and largely ignored during other transboundary bilateral negotiations, such as over water sharing and antiterrorism cooperation. The ratification of any agreement on territorial exchange in India and Pakistan (later Bangladesh) also required a constitutional amendment. The first attempt to transfer the enclaves was made in 1958, when India and Pakistan agreed to an exchange “without any consideration of territorial loss or gain” (the Indian lands within Bangladesh are considerably larger, see Box 1). A second deal, the Land Boundary Agreement (LBA) was signed in 1974 between India and newly independent Bangladesh to resolve all border disputes, including enclave exchange. Both agreements, however, became victim to fierce domestic politics and unstable bilateral relations, and remained largely unimplemented. In India, the transfer of an enclave was considered as a loss of territory to an enemy Muslim state. To break almost four decades of deadlock, the third initiative was taken in September 2011, when India and Bangladesh signed a Land Boundary Protocol (LBP) to implement the unresolved issues of the 1974 LBA. Yet the protocol lacked a specific timeframe to accomplish the exchange, and though implementation efforts commenced, including a population survey, the exchange continued to face domestic opposition in India.

Following Indian elections in 2014, new Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the BJP developed a constitutional amendment to resolve the enclave problem. Although uncertainty remained over ratification of the LBA in the Indian Parliament, the amendment unanimously passed both chambers. While Bangladesh had ratified the LBA in 1974, India took 41 years to approve this territorial transfer. Clearing the path for the transfer, Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and her Indian counterpart Modi exchanged Instruments of Ratification of the 1974 Land Boundary Agreement and its 2011 Protocol on June 6, 2015.

Choosing Sides

Under the 2011 protocol, enclave residents could choose to live in India or Bangladesh and be granted citizenship of the country of residence. For example, the resident of a Bangladeshi enclave in India who chose to remain in what is now Indian territory would receive Indian citizenship. Alternatively, those living in Indian enclaves in Bangladesh had the option to take Bangladeshi citizenship or be resettled to India.

An initial population survey was conducted in 2011, following drafting of the protocol. After the exchange was formalized in 2015, a second joint population survey was conducted in the 162 enclaves in July 2015 to identify residents’ citizenship or nationality preferences. Critics, including some residents, have said the surveys contain many discrepancies, for example, not counting residents who were away and not accurately recording household sizes. The 2015 survey recorded a total of 38,521 people living in 111 Indian enclaves inside Bangladesh and 14,863 people living in the 51 Bangladeshi enclaves within India. The majority of those in the Indian enclaves in Bangladesh chose to become Bangladeshi citizens and remain in their homes, while 989 people opted to retain Indian citizenship and be relocated to India, according to Indian government figures. On the other hand, all those living in Bangladeshi enclaves within India chose to become Indian citizens and remain in India. By November 30, 920 people from the Bangladeshi side had migrated to India while 61 Indian enclave residents changed their minds and remained in Bangladesh.

Belonging and National Identity

Belonging and national identity in India and Bangladesh are complex, historically rooted in Hindu-Muslim feuds and the division of India in 1947 first and foremost on the basis of religion. Following partition, territorial nationalism based on religion reached a new level of public consciousness, which was strongly reflected in the enclaves. Politically tailored, religion-based division pushed millions of people to move out of the newly independent state where they would be a minority (Muslims in India moved to Pakistan, while Hindus migrated in the other direction). At that time, Muslims in India and Hindus in Pakistan lived in fear of persecution. The enclaves were no exception. By the time of the exchange in 2015, many of those living in the Indian enclaves in Bangladesh were Muslims from across the border who, following partition, had traded their land in India with Hindus living in the enclaves in Bangladesh. The Hindus thus moved into the Indian mainland, while the Muslims moved into the Indian enclaves within Pakistan/Bangladesh. In most instances, these Muslims were unaware of the existence of the enclaves and the realities of enclave life, believing they had acquired land in Pakistan itself. This migration to and from the enclaves thus served as an escape from hostile local environments. Such exchanges of land and nationality began soon after partition and continued irregularly for decades.

With the breakthrough in 2015, enclave dwellers considered a multitude of factors in deciding which citizenship to acquire. Entrenched social divisions played a significant role in enclave dwellers’ decision-making on whether to resettle across borders or remain in their homes. For some remaining Hindu enclave dwellers within Bangladesh the environment had become too hostile, contributing to decisions to relocate to India. For those who chose to relocate, the sentiment that “India is for the Hindus and Bangladesh for the Muslims” may have factored into their migration, signifying the importance of religious identity in the construction of nationness and boundaries for some people. Religion, however, was not the only motivation. Enclave residents also considered deep-rooted attachment to the place where they had lived for generations—as evidenced by the vast majority who chose not to leave. Muslim enclave residents in India thus chose Indian citizenship, while some Hindu enclave residents in Bangladesh decided to become Bangladeshi. For those who chose to move to India, the stronger economy and the perception of greater job prospects and economic opportunities was another major factor.

Migration to the Desired Homeland and Way Forward

With the land exchange came a transfer of populations. As noted above, all of the Bangladeshi enclave residents in India chose to remain in India and are being integrated in Indian society. For the nearly 1,000 Indians in Bangladesh who chose to be relocated to India, the Indian High Commission in Dhaka provided travel passes for migration through particular border checkpoints. This cross-border movement of people through official coordination was the first of its kind on the subcontinent since partition.

India and Bangladesh agreed to complete the exchange by June 30, 2016, including physical transfer of enclaves and surrender of land parcels in adverse possession along with official boundary demarcations. One of the most crucial and complicated aspects involves exchanging information on land records. Most enclave residents are extremely poor and small landholdings are their only assets. For decades, enclave dwellers bought and sold land without valid documents or proper registration with authorities in India or Bangladesh to avoid dangerous and illegal border crossings. Only a few enclave residents have valid documents proving their ownership, and many are now in fear of losing the lands they either inherited or bought. For those resettled to India, some failed to sell their land and have petitioned the Cooch Behar district administration, where they have been housed in temporary camps, with details of their properties to ensure the Bangladesh government offers a fair price. At the same time, the Indian government is searching for land it can acquire and allocate to the resettled families.

The Indian government has arranged shelters for the relocated families in three resettlement camps in Cooch Behar district. The camps are intended to operate for two years, or until permanent settlements are built. Though the local administration is providing food and helping complete paperwork for national identification, employment cards, and other social services, the camps are encircled by wire fencing and authorities have restricted residents’ mobility. While many challenges remain including finding employment, school enrollment for the children, and land allocation, for some former enclave residents the camps offer more services, such as electricity and access to government, than they had before. The Indian bureaucracy has proven a major hurdle to integration efforts and service provision, however, as camp administrators must file requests with state officials, who in turn must communicate with the federal government, which may, depending on the request, then have to reach out to Bangladeshi authorities.

While integration efforts are slowly unfolding, local politicians in India’s West Bengal state have sought to claim their new constituents, petitioning the federal government to introduce a bill in Parliament making former enclave residents eligible to vote. This would apply to the approximately 15,800 Bangladeshis who became Indian citizens and the relocated Indians, according to the latest headcount as of early February 2016.

Life in the Former Enclaves

For the thousands of former enclave residents who remained in their homes, life continues much as it did before the exchange. Most have yet to receive their national ID cards, and new infrastructure projects to install electricity and build new roads, hospitals, and schools have been slow to show progress.

In December, the Indian Cabinet approved a three- to five-year rehabilitation package to aid integration of former enclave residents and territory, with funding of Rs 1,005.99 crore (about US $150 million). And in January, Bangladesh approved a Tk 1.8 billion (about US $22.9 million) development project for its 111 erstwhile enclaves, including supplying potable water and building hundreds of kilometers of new bridges and roads, local markets, mosques, and community centers—to be completed by 2018. These official packages look promising for physical development of the enclaves and benefits for the new citizens—if implemented as intended.

However, nearly seven decades without governance, problems related to lawlessness, land-holding complexities, and the influence of local politics might not be so easily resolved, and it remains to be seen if the complex history of the enclaves will end in success.

This article draws in part on the author’s PhD research, which was funded by the Department of Geography, University of Durham.

Sources

Ahmed, Zafar. 2016. ECNEC approves Tk 1.80 billion project for development of 111 former enclaves dwellers. Bdnews24.com, January 5, 2016. Available Online.

Alam, Shafiqul. 2015. Heartbreak as Bangladesh-India land swap splits families. Agence France-Presse, July 31, 2015. Available Online.

Chatterji, Joya. 1999. The Fashioning of a Frontier: the Radcliffe Line and Bengal’s Border Landscape, 1947-1952. Modern Asian Studies 33 (1): 185-242.

---. 2007. The Spoils of Partition. Bengal & India 1947-1967. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Economist, The. 2015. Mapped Out. The Economist, June 13, 2015. Available Online.

Ghosal, Aniruddah. 2015. Indo-Bangla land swap: The new Indians. The Indian Express, December 6, 2015. Available Online.

Hindu, The. 2015. Land Pact Rollout in Next 11 Months. The Hindu, June 13, 2015. Available Online.

Jones, Reece. 2009. Sovereignty and Statelessness in the Border Enclaves of India and Bangladesh. Political Geography 28 (6): 373-81.

Kudaisya, Gyanesh. 1997. Divided Landscapes, Fragmented Identities: East Bengal Refugees and their Rehabilitation in India, 1947-1979. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 17 (1): 24-39.

Kumar, Radha. 1997. The Troubled History of Partition. Foreign Affairs 76 (1): 23-34.

Ministry of External Affairs (MEA), India. N.d. India and Bangladesh Land Boundary Agreement. New Delhi: MEA. Available Online.

---. 2015. Exchange of enclaves between India and Bangladesh. Press release, November 20, 2015. Available Online.

Mohan, Saumitra. 2015. India-Bangladesh Enclave Exchange: Some Concerns. Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, October 20, 2015. Available Online.

Santoshini, Sarita. 2016. Hope for a Better Life on the India-Bangladesh Border. City Lab, January 15, 2016. Available Online.

Sen, Gautam. 2015. For Successful Implementation of the Land Boundary Agreement with Bangladesh. Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, December 29, 2015. Available Online.

Shewly, Hosna J. 2012. Life, the Law, and Politics of Abandonment: Everyday Geographies of the Enclaves in India and Bangladesh. PhD Dissertation, Durham University, September 2012. Available Online.

---. 2013. Abandoned Spaces and Bare Life in the Enclaves of the India-Bangladesh Border. Political Geography 32: 23-31.

---. 2015. Citizenship, Abandonment & Resistance in the India-Bangladesh Borderland. Geoforum 67: 14-23.

---. 2016. Survival Mobilities: Tactics, Legality & Mobility of Undocumented Borderland Citizens in India & Bangladesh. Mobilities, January 13, 2016.

Mazumdar Jaideep and Pinak Priya Bhattacharya. 2014. Border Dwellers between India and Bangladesh: ‘Now We Can Live and Die with Dignity.’ The Times of India, December 7, 2014. Available Online.

Times of India, The. 2015. India, Bangladesh Launch Survey in Enclaves over Nationality. The Times of India, July 6, 2015. Available Online.

---. 2016. Parl bill on enclave voting rights? The Times of India, February 8, 2016. Available Online.

Van Schendel, Willem. 2002. Stateless in South Asia: The Making of the Indo-Bangladesh Enclaves. The Journal of Asian Studies 61 (1): 115-47.

---. 2005. The Bengal Borderland: Beyond State and Nation in South Asia. London: Anthem Press.

Vinokurov, Evgeny. 2007. A Theory of Enclaves. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Whyte, Brendan R. 2002. Waiting for the Esquimo: An Historical and Documentary Study of the Cooch Behar Enclaves of India and Bangladesh. Research Paper 8, School of Anthropology, Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Melbourne, 2002. Available Online.