You are here

Kenyan Migration to the Gulf Countries: Balancing Economic Interests and Worker Protection

A booming economy in the United Arab Emirates has attracted labor migrants from many countries, including Kenya. (Photo: Jake Brewer)

In recent years, temporary labor migration from Kenya to the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has increased significantly. Seeking to fill labor shortages in sectors such as construction and other service-based jobs ahead of the UAE Expo in 2020 and the Qatar World Cup in 2022, some Gulf countries and employers have turned to Kenya as a fresh source of inexpensive labor—particularly as Asian countries impose restrictions on sending workers to the region. For Kenyans, rising unemployment and instability at home, combined with the difficulty of gaining entry to Western countries and the GCC region’s economic growth and proximity, have piqued the interest of would-be migrants.

At the same time, this new migration presents significant challenges for Kenya and the GCC countries, particularly in the area of labor rights. Migrants working in the region often fall through the cracks of the regulatory system and are vulnerable to illegal and/or unethical treatment by agents and employers. In responding to reports of abuse from its nationals in the region, Kenya is faced with a dilemma: how to protect its diaspora while maintaining strong bilateral relationships that are crucial to its own economic interests. To this point, some observers suggest that Kenya has prioritized its economic interests over the welfare of its migrant workers in the region. The country also has yet to emulate aspects of the worker protection infrastructure instituted by Asian countries that deploy significant numbers of workers to the Gulf.

Drawing on government and media reports and stakeholder interviews from the authors’ fieldwork, this article explores Kenyan migration trends in the GCC region, particularly the Kenya-UAE corridor. It examines the competing motivations behind Kenya’s approach to emigration policy, and the opportunities and challenges the country encounters when engaging with its migrants and governments in the Gulf.

An Overview of Kenyan Labor Migration

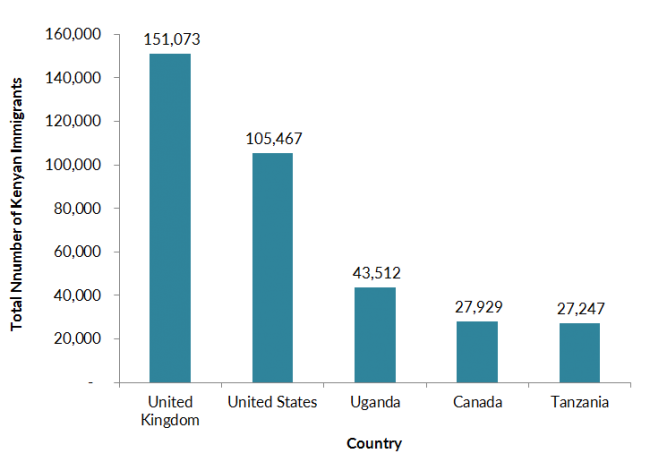

Emigration trends over the past few decades suggest the growing mobility, scale, and range of destinations of Kenyan migrant populations globally. Since the 1970s, many high-skilled Kenyans have emigrated to Western countries as well as within Africa, predominantly in search of better opportunities and greater political stability. Starting in the 1990s, however, Kenyan migration intensified, as migrants increasingly left for high-skilled work primarily in Western countries. More than 455,000 Kenyans lived abroad in 2015, compared to about 237,000 in 1990, according to United Nations data. The United Kingdom has become a top destination for Kenyan migrants, who numbered more than 151,000 in that country alone in 2015. Other top destinations include Tanzania, the United States, Uganda, and Canada (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Countries with the Largest Populations of Kenyan Immigrants, 2015

Source: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “Trends in International Migrant Stock: Migrants by Origin and Destination” (2015), available online.

Labor migration has played a vital role in Kenya’s socioeconomic development; in 2015, remittances represented 3 percent of gross domestic product, totaling US $1.55 billion, according to the Central Bank of Kenya. Nearly half of remittances came from North America, and one-third from Europe. Most Western-based Kenyans tend to be highly skilled and migrate via family reunification channels or routes such as the U.S. diversity visa program, asylum programs, or through illegal immigration.

Kenyan Migration to the GCC Countries

In contrast, semi- and low-skilled workers have dominated Kenyan migration to the Gulf. Driven by a lack of opportunities at home, Kenyans are recruited as domestic workers, construction laborers, cleaners, hospitality servers, security officers, and taxi drivers. Migrants in these industries are often vulnerable to illegal and/or unethical recruitment practices, labor exploitation, and deskilling (occupational downward mobility). In particular, Kenyan domestic workers, who began arriving significantly in the Gulf countries after Ethiopia temporarily banned the deployment of its domestic workers in 2013, are often misled with fake job offers to lure them to migrate.

In response to a high rate of reported labor abuses among Kenyan workers in the region, particularly domestic workers, Kenya imposed a ban on labor migration to the GCC countries in 2012; it then overturned the ban in November 2013. While the ban was in place, some would-be migrants paid corrupt officials in order to secure employment in the Gulf countries. Some observers argue the government lifted the ban in response to the strong lobbying effort made by recruitment agency associations in Kenya.

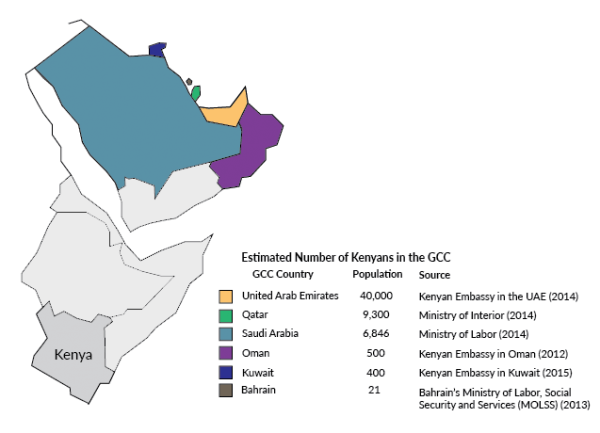

Based on population data from national ministries and Kenyan embassies, which are not always in accord, between 57,000 and 100,000 Kenyans live in GCC countries; most in the United Arab Emirates (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Kenyan Migrants in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Countries

Note: Estimates exclude dependents, tourist visa holders, and unauthorized migrants.

Sources: For Bahrain: International Organization for Migration (IOM), “Migration in Kenya: A Country Profile” (2015), available online; Kuwait: BQ Magazine, “Kuwait Population – By Nationality” (2015), available online; Oman: Diaspora Messenger, “Kenya ban on domestic workers not to affect Oman” (2012), available online; Qatar: BQ Magazine, “Qatar Population – By Nationality” (2014), available online; Saudi Arabia: Gulf Labor Markets and Migration, “Saudi Arabia work visas allotted for employment in the private sector by country of citizenship and sex holder” (2014), available online; United Arab Emirates: BQ Magazine, “UAE Population – By Nationality” (2014), available online.

Emerging Policy Framework

Recognizing the growing economic importance of its diaspora, Kenya has begun work on legislation to address issues surrounding emigration. In 2007, the government sought to curb recruitment malpractices by enacting the Labor Institutions Act, which regulates cross-border recruitment by private employment agencies, including the registration requirements, agents’ obligations, and penalties for violations. The law’s subsequent amendments in 2014 regulated recruitment costs, shifting the responsibility for payment to the recruitment agencies, except for a service fee that should not exceed 25 percent of the workers’ first monthly salary.

In 2009, Kenya drafted an overall migration policy, followed the next year by a national labor migration policy. These policies, which remain in draft form, encompass the deployment of Kenyan workers, their labor rights and protections while abroad, and reintegration.

In 2015, Kenya implemented a diaspora policy focused on harnessing the potential of its nationals abroad to contribute to the country’s economic development. The policy seeks to facilitate remittance inflows.

Despite these mechanisms proposed to enhance the protection of workers abroad, Kenya has not developed a comprehensive strategy to address reported labor abuses, particularly in the GCC region. Kenya has not created the same protection infrastructure as key migrant-sending Asian countries, such as an official labor and welfare office, safe shelter houses, and other protection initiatives. Furthermore, Kenya lacks detailed strategies and capacity for implementation of its regulations. The lack of such labor laws, policies, and institutions paves the way for systematic labor abuses and creates an exploitative space for recruitment agencies, Human Rights Watch contends.

Balancing National Interests in the Gulf

Kenya has increasingly been faced with a dilemma: how to prioritize its economic interests through bilateral trade relations while also guaranteeing protection for its citizens abroad, whose well-being often rests with key trading partners. While Kenya’s labor protection policy for workers abroad remains limited, its economic diplomacy in the GCC region has intensified with the pursuit of various trade partnerships. In 2011, Kenya and the United Arab Emirates signed an agreement to increase bilateral trade. The agreement seeks to prevent double taxation on businesses, finalize agreements on customs support, and promote and protect investments. In 2014, Kenya signed a major agreement with Qatar to increase bilateral maritime cooperation by creating a direct shipping route between Mombasa and Doha.

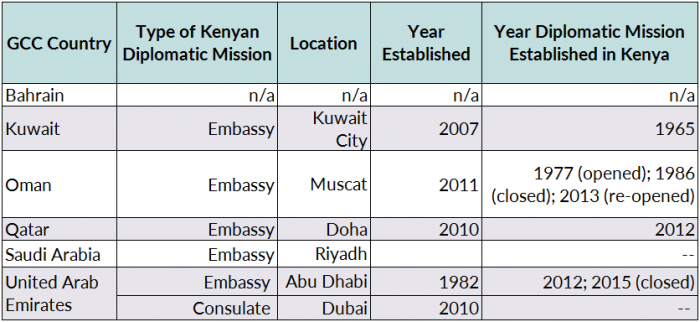

Kenya also has bolstered its diplomatic presence in the region, establishing new embassies and consulates, while GCC governments simultaneously opened (or reopened) their diplomatic missions in Kenya.

Table 1. Kenyan and GCC Diplomatic Missions

Sources: Kenyan government has established diplomatic missions in the Gulf countries, including the following: Kenyan Embassy in Qatar (2016), available online; Kenyan Embassy in Oman, “Kenya –Oman Bilateral Relations” (2016), available online; Kenyan Embassy in Kuwait, “A Note from the Ambassador” (2016), available online; Kenyan Embassy in Abu Dhabi (2016), available online; Kenyan Embassy in Riyadh – Saudi Arabia (2016), available online. The Gulf countries have also recently founded diplomatic missions in Kenya, including Qatar: Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2016), available online; Kuwait: Kuwait Times, “Kenya –spearheading developing in East Africa” (2013), available online; United Arab Emirates: Business Daily Africa, “UAE closes Nairobi embassy amid falling trade” (2015), available online; Saudi Arabia Embassy in Kenya (2016), available online.

Meanwhile, Kenya has done little to directly engage these countries in addressing labor issues affecting its workers. National human-rights organizations including Trace Kenya and Solidarity with Women in Distress (SOLWODI) have accused the government of playing a public relations game while accomplishing little of substance on labor rights—suggesting Kenya may be prioritizing its economic interests over the welfare of its nationals in the Gulf region.

The Role of Aid and Finance as Soft Power

Faced with growing demand for inexpensive labor, Gulf countries have also taken action to develop stronger diplomatic and trade relationships with sub-Saharan African countries. In 2014, for example, the UAE government created a consular assistance and visa center in Nairobi to facilitate the entry of Kenyan workers into the United Arab Emirates. The establishment of GCC diplomatic missions in Kenya helped these countries pursue their economic interests via investment and labor cooperation.

Furthermore, Gulf countries—whether intentionally or not—offer Kenya and other countries humanitarian aid as a soft power means to assert their influence abroad. Saudi Arabia, which has emerged as the world’s largest non-Western humanitarian donor, has funded various projects in Kenya, including development of infrastructure for transportation, water, irrigation, and agriculture. In addition, between 2010 and 2012, the UAE Ministry of International Cooperation and Development extended more than US $7 million in humanitarian aid and development assistance to Kenya. Beyond government aid, organizations such as Dar Al Bern, which runs 80 charity programs in Kenya, as well as private-sector entities such as Etihad, the UAE national airline, are involved in building mosques, digging wells, handing out blankets and school supplies in underprivileged communities, and sponsoring orphans and Quranic teachers.

Some contend this aid, in addition to economic benefits accruing to Kenya in the form of remittances, investments, and employment opportunities, affects the country’s capacity to assert itself with respect to labor migration and protection issues.

The Kenya-UAE Migration Corridor and Policies

Kenyan migration to the United Arab Emirates illustrates the challenges facing labor-sending and receiving countries on worker protection. The United Arab Emirates is one of the largest trading partners for Kenya in the Middle East, and is also the preferred destination in the GCC region for Kenyan migrants, due to perceived higher wages, better living and working conditions, and the country's stability.

Given a bilateral deal signed by both countries in 2015 to recruit 100,000 Kenyans for jobs in the United Arab Emirates, Kenyan flows are expected to increase in the coming years. The two countries are negotiating a draft agreement on labor protection, according to one Kenyan official in the United Arab Emirates.

Unlike many Asian labor-sending countries—India, Indonesia, and the Philippines, among them—Kenya has no formal institutions such as labor or welfare offices in the United Arab Emirates to protect its nationals from abuse and exploitation. The Kenyan diplomatic missions lack well-developed grievance and dispute resolution programs, counseling mechanisms, postarrival orientation programs, and contract verification and monitoring. While Kenya set up a hotline in the United Arab Emirates for distressed workers seeking assistance, its diplomatic missions lack the institutional resources and mechanisms to effectively address complaints. Because these institutions are understaffed, front-line Kenyan authorities stationed in GCC countries lack full capacity to enforce labor protection and migration policy mandates.

In the United Arab Emirates, Kenyan migrants have brought numerous labor complaints to the attention of their respective consulates or embassies, or directly to that of the host country labor ministry. Reported labor complaints include contract substitution, illegal and unethical recruitment practices (mainly on overcharging fees), and working violations (i.e. illegal deductions of wages, restricted labor market mobility, and withholding of passports), as well as trafficking and servitude.

In particular, Kenyan domestic workers have reported physical, financial, and in some cases sexual maltreatment by their employers. Domestic workers also have voiced concern about the limited access to dispute resolution and mediation, given their exclusion from the governing labor law in the host country. This particular case illustrates the institutional, administrative, and policy challenges facing both governments in effectively regulating and addressing the labor complaints raised by migrants.

While some Kenyan migrants are aware of embassy labor-related services, many report feeling discouraged by perceived corruption and lack of interest in protecting their rights, and as a result often do not report their complaints to the embassy or seek assistance. Some groups even allege the government is complicit in illegal labor practices; Haki Africa, a labor-rights lobby group in Kenya, claimed, for example, that Kenyan government authorities owned ten or more illegal recruitment agencies that deploy workers to the Middle East.

Such embedded distrust of Kenya’s institutions is partly due to the perceived weakness of the Kenyan embassy in championing workers’ labor rights. This further undermines the legitimacy of these institutions and limits the government's ability to serve as a conduit in extending protection to its nationals. Although some workers reportedly have been assisted in resolving their grievances, it is unclear whether embassy officials have been able to penalize or blacklist employers or sponsors for violating labor rights. This critical gap raises questions about Kenya’s migration governance priorities and capacity in the GCC countries.

The following sections highlight some of the most critical labor rights challenges Kenya faces in the United Arab Emirates.

Recruitment Practices

Illegal and unethical recruitment practices remain rampant, posing challenges for governments at origin and destination. Kenya-based nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), including Trace Kenya and Human Rights Agenda, report that unlicensed recruitment agencies or brokers in Kenya continue to deploy significant numbers of migrants to the Gulf countries, despite increasing government restrictions on recruitment or deployment abroad. The authors’ fieldwork has found that these agents charge would-be migrants between US $1,225 and $2,200 for airfare, temporary accommodation, visa documentation, and food—fees that exceed those charged in Asian countries. Because of the high recruitment costs, many Kenyans have opted to enter the Gulf countries on tourist visas, often sponsored by friends, family members, or trusted agents in the region. Illegal recruitment—often perpetrated by agents and family members—thus perpetuates the migration (including illegal) of Kenyans to the GCC countries

Growing reports of abuse by Kenyans abroad have spurred Kenyan authorities to crack down in recent years on recruitment agencies that skirt the law. In 2013, the Kenyan government arrested three Qatar-based nationals from India and the United Kingdom who were operating an agency without properly following regulations. In September 2014, the government revoked 930 licenses of recruitment agencies found to be violating regulations in deploying Kenyans to the Middle East, particularly the GCC countries (however, many of these agencies subsequently reopened). The Kenyan Ministry of Labor also created a new administrative process, whereby recruitment agencies are legally mandated by the government to approve all proposed contracts before nationals are deployed. The Kenyan Ministry of Labor formed a Task Force in 2015 to investigate implementation of Kenya’s policies on labor migration particularly to the Middle East, and to review the effectiveness of policies toward recruitment agencies. However, while these efforts are a significant step forward in addressing labor violations, available reports from local NGOs and fieldwork findings indicate labor abuses remain rampant and illegal deployment of Kenyan domestic workers has continued to grow despite ongoing regulatory restrictions.

Contract Substitutions

Like other migrant workers in the GCC region, Kenyans often face contract substitutions either at origin or destination, whereby agents—both legal and illegal—deliberately provide false contract information and lure prospective applicants to accept the employment offer. This asymmetric information has not only resulted in labor abuses (i.e. false promises and cheating) within the market, but also has negatively affected the wages, and, in some cases, triggered the early departure of migrants from the Gulf countries.

Lack of Bilateral Labor Agreements

Despite signing a trade agreement in 2011 and despite the increasing presence of Kenyan domestic workers in the United Arab Emirates, the two governments have not signed a labor accord. Furthermore, there has been no public reporting of labor protections for Kenyan migrant workers in existing bilateral agreements or diplomatic discussions. Given domestic workers’ exclusion from national labor law protections in the GCC countries, the lack of an established bilateral labor agreement remains a critical gap in protection.

Labor Migration Key for Economic Development at Both Ends of the Migration Continuum

Kenya’s ability to send nationals to work in the United Arab Emirates and other GCC countries provides a source of remittances and regional diplomatic relations important to its economic development. Gulf countries also benefit, given increasing labor shortages and the domestic-worker deployment bans that some sending countries in Asia have imposed. As a result, access to Kenyan and sub-Saharan African labor more broadly is key to the GCC region’s long-term development.

Kenya has only recently institutionalized efforts to send migrant workers abroad to GCC countries and create a framework to protect them. In the absence of strong bilateral labor accords and government institutions to protect workers during the recruitment and deployment phases, however, Kenya has opened itself to the perception that it is prioritizing its economic interests and diplomatic relationships in the Gulf over the labor rights and well-being of its citizens abroad. Until it addresses this governance gap, the Kenyan government will have practical challenges in upholding its national migration policies and may be leaving Kenyan migrant workers vulnerable.

Sources

Abdul, Binsal. 2015. No ban on Kenyan women who want to work as maids. Gulf News. February 28, 2015. Available Online.

Mendoza, Dovelyn Rannveig. 2010. Migration's Middlemen: Regulating Recruitment Agencies in the Philippines-United Arab Emirates Corridor. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available Online.

Al-Yahya, Khalid and Nathalie Fustier. 2011. Saudi Arabia as a Humanitarian Donor: High Potential, Little Institutionalization. Berlin: Global Public Policy Institute. Available Online.

Amran, Athman. 2011. Saudi Arabia loans sh1.6 b Kenya road construction. Standard Media, September 23, 2011. Available Online.

Atieno, Winnie. 2014. Lobby points fingers at MPs in Saudi jobs scandal. Daily Nation, October 22, 2014. Available Online.

Baraka FM. 2015. Kenyans lose Kshs. 4 million to fake recruitment agencies. Baraka FM. Available Online.

Capital Reporter. 2012. Be wary of agents, Saudi envoy warns Kenyans. Capital News. Available Online.

Central Bank of Kenya. 2016. Diaspora Remittances. Accessed May 11, 2016. Available Online.

Danish Refugee Council. 2016. Kenya Country Profile. Accessed May 11, 2016. Available Online.

Doha News Team. 2013. Three Qatar-based expats arrested in Kenya over alleged ‘illegal recruitment’ allegations. Doha News, June 11, 2013. Available Online.

Emirates 24/7. 2014. UAE visa issuing centre in Nairboi. Emirates 24/7. November 18, 2014. Available Online.

European Commission. 2014. European Union, Trade in Goods with Kenya. European Commission. Accessed May 11, 2016. Available Online.

Human Rights Watch. 2014. “I already bought you”: Abuse and exploitation of female migrant domestic workers in the United Arab Emirates. Available Online.

International Organization Migration.2015. Migration in Kenya: A Country Profile 2015. Nairobi: International Organization for Migration. Available Online.

Kenyan Embassy Saudi Arabia. 2016. Kenyan-Saudi Arabia: Deepening of Bilateral Relations. Accessed May 11, 2016. Available Online.

Kiberenge, Kenfrey. 2012. Kenyan women stuck in a container in Saudi Arabia. Standard Media, July 29, 2012. Available Online.

Malit, Jr., Froilan, and George Naufal. Asymmetric Information Under the GCC Kafala Sponsorship System: Impacts on Foreign Domestic Workers’ Income and Employment Status in the GCC Countries. Ithaca, NY: Industrial and Labor Relations School, Cornell University. Available Online.

Malit, Jr., Froilan and Ali Al Youha. 2013. Labor Migration in the United Arab Emirates: Challenges and Responses. Migration Information Source. September 18, 2013. Available Online.

---. 2014. Civil Society in Qatar and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Countries: Emerging Dilemmas and Opportunities. Migration Information Source. April 9, 2014. Available Online.

Malit, Jr., Froilan and Oliver Tchiapep. 2013. Labor Migration and Deskilling in the United Arab Emirates: Impacts on Cameroonian Labor Migrations. Ithaca, NY: Industrial and Labor Relations School, Cornell University. Available Online.

Migration Policy Institute. 2015. The Kenyan Diaspora in the United States. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available Online.

Migiro, Katy. 2015. Desperate Kenyan maids abused in Middle East despite ban. Reuters. Available Online.

Mouawiya, Al Awad. 2010. The Cost of Foreign Labor in the United Arab Emirates. Dubai: Institute for Social and Economic Research. Available Online.

Namlola, Juma and Samuel Karanda. 2015. Kenya signs deal to export 100,000 workers to the UAE. Business Daily Africa. Available Online.

Naufal, George and Ismail Genc. 2012. Expats and the Labor Force: The Story of the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Available Online.

Ngugi, Brian. 2014. Kenyan government to combat migrant abuse in the Gulf. Equal Times, October 13, 2014. Available Online.

Obdhiambo, Allan. 2011. Kenya frees more trade partners from double tax. Business Daily Africa, November 23, 2011. Available Online.

Otuki, Neville. 2015. UAE closes Nairobi embassy amid falling trade. Business Daily Africa, August 21, 2015. Available Online.

United Arab Emirates Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation. 2015. UAE Ambassador meets Minister of Foreign Affairs of Kenya. November 11, 2015. Available Online.

United Arab Emirates Ministry of International Cooperation and Development. 2013. Kenya – Country Profile. Accessed May 11, 2016. Available Online.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2015. Trends in International Migrant Stock: Migrants by Destination and Origin. United Nations database POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev.2015. Accessed May 11, 2016. Available Online.