You are here

As Lesvos Battles Migration Crisis Fatigue, the Value of Centralized Migration Decision-Making Is Questioned

Outside Moria refugee camp on the island of Lesvos, Greece. (Photo: OSCE Parliamentary Assembly)

While arrivals of migrants and asylum seekers to the Greek islands are dramatically less than during the 2015-16 European migration crisis when Greece received more than 853,000 migrants, they remain a feature of daily life. More than 33,000 migrants arrived during the first eight months of 2019, according to International Organization for Migration (IOM) estimates, with the flows rising sharply in July and August. The vast majority have come by sea, landing on islands in the Aegean, where approximately 25,250 refugees and migrants resided as of September in camps whose grim living conditions have been sharply criticized.

The continued pace of new arrivals, most from Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), comes as the Greek islands face major challenges in hosting newcomers who remain stuck in camps for months amid major case-processing delays. Among the difficulties: serious overcrowding, insufficient resources to provide access to health care and other necessary services, lack of professional personnel to process asylum claims, and inadequate coordination among the various actors to make living conditions humane. The Moria refugee registration camp on Lesvos, designed for 3,000 people, now holds well more than three times as many, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) reported recently.

One big problem is unpredictability in the number of arrivals. For example, on one day in August 2019, Lesvos saw the arrival of 13 boats carrying more than 500 migrants. Accommodating such large numbers in one day poses logical and practical challenges for an island with reception centers that are already well past capacity. Contrary to Italy, which has recently barred migrant rescue boats from docking in its ports, Greece continues to admit and process those migrants who land on its shores.

Yet despite governmental and community support, crisis fatigue has set in and Greek residents seek the return to normality and resumption of tourism that remains the islands’ economic lifeline. Moreover, Greece is still struggling to recover from its decade-long economic crisis, although some hopeful signs are appearing on the horizon. A new government elected in July 2019, the New Democracy party, has promised to usher in major economic, political, and social reforms that have been received favorably by the international community and foreign markets.

While the landscape has changed on the ground in the past few years and conditions for migrants living on the Greek islands has moved away from provision of immediate first aid to getting children into school, for example, decisions regarding funding and other resource allocations to address the needs of these refugees and other migrants have not. The paradox is that while migration policymaking and related decisions are negotiated in Brussels for EU countries and in Athens at the national level, the effects are felt by the urban and rural localities whose governments have very little say in how and where money is allocated.

Many migration analysts, local government officials, and international actors alike have suggested that local units of administration are the better choice for making decisions about the provision of shelter and other services for migrants. Bringing their voices into what has been a centralized decision-making process would give local authorities more agency to do what they are already doing, mainly providing for migrants’ immediate needs and creating initiatives to make them a part of society, and not an appendage to it.

But decentralizing the migrant resource allocation structure brings up the thorny issue of multilevel governance and requires the devolution of power. Reconfiguring authority is a tricky business and necessitates structural transformation as well as changes in mindset. Most European countries—even stalwarts of centralization such as Greece—have subnational levels of government that have taken up the task of accommodating migrants and asylum seekers in their neighborhoods.

Based on interviews with local municipal authorities, international and local NGO representatives, the manager of the locally run Kara Tepe refugee hospitality center, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) representatives, and local business owners on Lesvos, this article outlines successes that subnational jurisdictions—in coordination with other actors—have had in hosting migrants. It begins with observations from the hospitality center and refugee camp on Lesvos, and then places that within the context of the Greek state.

Observations from Lesvos

In 2015, more than 500,000 migrants and asylum seekers were hosted on Lesvos, prompting the island to develop its own response to the influx. Initially, locals rushed to help, their efforts adding on to those of UNHCR, international and local nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), regional and local government agencies, and volunteer groups that to this day still have operations on the islands. In those early days, Greeks empathized with the refugees—despite the strain from the global financial crisis—knowing well what it is like to be a foreigner in another country, given the sizeable Greek diasporic population. However, four years later, crisis fatigue has set in, resources have been depleted, many NGOs initially assisting have left, and locals are struggling to attract tourists. Unemployment remains high, and Lesvos, like many other islands in Greece, longs for the return of normalcy and opportunities for residents impoverished during the economic crisis.

Despite a lack of available space, the municipality of Lesvos created its own reception site for asylum seekers, the “Hospitality Centre for Refugees and Migrants (Kara Tepe),” which began operating in April 2015. This center largely was created as a response to the conditions at the Moria refugee processing center, which opened in 2013 on the grounds of a former military base. The Moria camp has been the site of riots and other clashes because of persistent overcrowding and other problems. In making the decision to open Kara Tepe after the port of Mytilene filled with refugees sleeping in tents in 2015, the mayor and an appointed site manager for Kara Tepe arranged to get UNHCR assistance and contacted both international and local NGOs as well, mayoral spokesman Marios Andriotis told the author during an interview in 2018.

Kara Tepe, which does not exceed its capacity of 1,200, has not been subject to the same reports of squalid conditions and overcrowding as Moria. Kara Temp camp manager Stavros Mirogiannis has set up a system of general rules emphasizing the safety of residents, and demarcated two main areas: one for activities and a residential area where some 260 vulnerable families each have their own container dwelling. The center is well organized, runs soccer academies for refugee children, and has child-friendly spaces for language lessons and other skills and crafts. The center has a theater that screens films in Arabic and Farsi, a space for unaccompanied minors run by the Greek NGO METAdrasi, and a safe space for women run by the International Rescue Committee.

Mirogiannis’ tenure as site manager ended in August 2019, amid a change in local government in Mytilene. When word of his departure reached center residents, they staged a demonstration in protest, chanting “We need Stavros.” Though Mirogiannis has reapplied for the position, it remains to be seen whether someone else will replace him, and what that will mean for the refugee center’s future.

In stark contrast to Kara Tepe, Moria, a former military camp before being converted into a refugee “hotspot” to house refugees seeking asylum, operates well beyond its capacity. The Moria camp has limited food, water, and other necessities; a huge sanitation problem; and little in the way of recreational and similar resources to make conditions livable. Safety and housing are the biggest challenges, and outside are makeshift tents filled with refugees who cannot physically fit within the barbed-wire confines of the official camp. The Moria camp has been condemned by numerous organizations, including MSF, Oxfam, and Amnesty International. Despite the European Union providing the Greek government some 5.4 million euros to set up and operate the camp, running overcapacity has made decent living conditions impossible. There are limited medical personnel and supplies, and disease and illness are rampant. Built originally as a waystation for those fleeing Syria, Afghanistan, and Iraq, Moria turned into a detention camp where some have been waiting for years for their asylum claims to be settled.

Kara Tepe’s successes offer illustration that subnational actors often know how to allocate and use funds better than those on a national or supranational level when it comes to housing and providing reception services to migrants and asylum seekers. Yet centralized control of resources blocks the ability of local governments to succeed at times. For example, when sanitation trucks operated by Lesvos needed repair after taking on significant new burdens collecting trash from the migrant camps, the prefecture and Greek central government refused repeated requests to reimburse the municipality. Similarly, Lesvos would like to develop its own municipal police force to patrol the camps and the town, but town leaders have neither the funds nor the power to do so.

The Case of Greece and Migration Governance

Dysfunction has plagued Greece’s decision-making processes since 1974. Corruption, patronage, cronyism, and party populism explain much of why Greek public administration does not function effectively. This problem is not specific to Greece, but the country’s experiences with the global recession in 2008 and subsequent dramatic economic meltdown have made it uniquely vulnerable. Further, the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund, and the European Central Bank required Greece to undergo a series of significant structural changes in order to receive bailout money.

In addition, Ministerial Decisions (Υπουργικές Αποφάσεις), formal mandates usually initiated by ministers of government to regulate specific policies, may change how laws are implemented, further diluting the rule of law. These formal mandates have been used to regulate immigration policy but have not necessarily been effective in providing for the adjustments needed to address changing concerns on the ground. For example, many ministerial decisions act as amendments to previous laws that set the maximum number of resident permits for third-country nationals, and for determining these newcomers’ access to work permits and health care. Seeking to alleviate the pressure on the islands, the Greek government’s recently formed Council on Foreign Affairs and Defense (KYSEA) in August decided to transfer refugees from overcrowded camps to the mainland, facilitate the reunification of unaccompanied minors with relatives in other EU countries, and, more controversially, abolish appeals for rejected asylum seekers to speed their deportation.

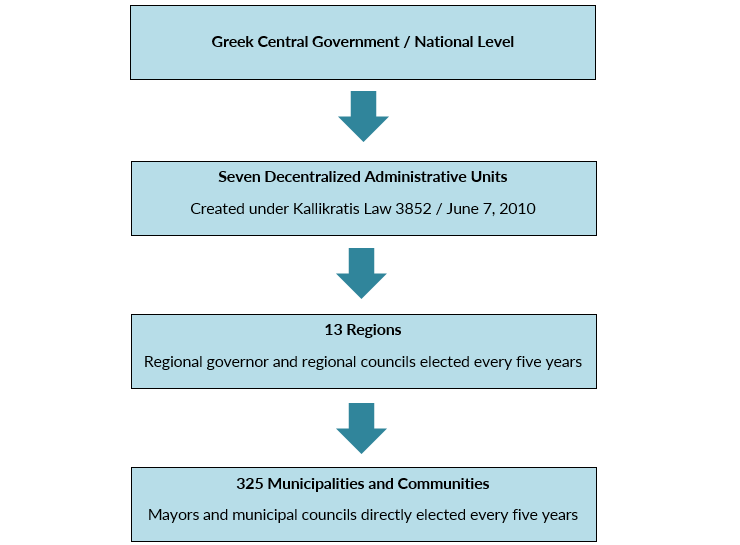

Greece has likewise struggled decentralizing its top-heavy state. In an attempt to remedy the problem, two major reforms occurred via the Kapodistria and Kallikratis laws. The Kallikratis Law, implemented in 2011, delegated certain administrative powers to seven administrative units as well as the 13 regions, each led by a regional governor who is elected by popular vote. The May 2019 municipal elections held in conjunction with European parliamentary elections saw a substantial win for center-right New Democracy, which triggered a snap election on July 7, 2019 that resulted in New Democracy claiming 158 seats in the 300-seat Greek Parliament and forming a new government. The new government created a Deputy Minister for Migration, George Koumoutsakos, under the Civil Protection Ministry, changing the previous structural leadership for migration policy. New measures recently announced by the government include adding more personnel on the islands for interviewing asylum seekers and ensuring that the March 2016 EU-Turkey agreement, intended to slow irregular migration through Turkey into Europe, is implemented.

Figure 1. Greek National and Subnational Administrative Structure

Source: Author’s rendering based on the Kallikratis Law.

The subnational units of government created by the 2011 law are meant to facilitate better communication between the central ministries and the regions. They are responsible for urban planning and regulations governing everything from municipal buildings to port authorities and forest management, among others. Other provisions under the Kallikratis Law extend certain responsibilities to municipalities for various social policies, including day care, and programs for the elderly, immigrants, and provision of public health services. Separately, the national government in 2010 created Migrant Integration Councils (MICs), tasking them with encouraging immigrants to participate in the MICs at the local level. In opening a direct channel to the local government, MICs were designed to give migrants more agency in their integration experience.

In theory, MICs and subnational units such as municipalities can receive permission to make decisions affecting local migrant populations from both the decentralized administrative units and the regions, but this occurs unevenly and much depends on the competencies and initiative of local governmental officials. In the case of Lesvos, the municipality sought funds from the regional governor to provide better services for refugees, but as mayoral spokesman Andriotis pointed out, regional governors often have their own political agendas or are of an opposing political party, and are therefore not willing to allocate funds.

In effect, despite the Kallikratis Law, municipalities and communities continue to be dependent on the regional and central governments to dispense resources to them since they have no independent means of revenue collection or dispensation. Additionally, since the economic crisis, municipalities have been preoccupied with providing services for Greeks who were hit hard by austerity measures. Local officials often have been confronted by Greek citizens who resent money being allocated for refugee accommodation and integration. Effectively, the 2015-16 migration surge created another humanitarian emergency that a financially struggling Greece was ill prepared to handle, especially at the local level.

Tensions and Opportunities for Providing Migrant Integration Services at the Local Level

In February 2016, Greece went from being a country of transit to one of destination when borders were closed with the (recently renamed) Republic of North Macedonia, blocking refugee movement This, combined with other EU Member States’ unwillingness to accept reallocation of refugees from Greece, have generated what observers describe as the country’s next challenge: creating a comprehensive plan for integration of asylum seekers who remain within its borders. Allowing subnational jurisdictions to seek and receive national and EU funds would initially expand safe accommodation for migrants and asylum seekers at ports of entry and for their integration into society thereafter.

In theory, Greece’s subnational units of government may shape local social policies, but the Greek state is highly centralized and EU funding goes directly to the national level. For example, resources for hosting migrants and asylum seekers are funneled to the ministerial level and then disbursed to localities. As members take their seats in the newly elected European Parliament, one of their first tasks will be to allocate funds for the next budget, forecasting spending through 2027. What funds will be set aside for the European Social Fund and smaller Asylum, Migration, and Integration Fund will substantially affect migration policies in EU Member States.

As suggested by Electra Petracou and colleagues, as well as Peter Scholten, EU funding could be more effectively used if local units of government, along with other local actors, were allocated funding directly and in ways that they could disburse on their own. The disconnect between available resources and where they are most needed could be resolved with local input. Those who are working with asylum seekers and other migrants have a much better idea of how EU money can be utilized to resolve local issues, as demonstrated by the case of Lesvos.

Greece represents a complicated case when it comes to providing services for migrants, its reality exacerbated by austerity policies and the debt crisis. Animosity has developed between migrants and local citizens, who often believe incorrectly that it is the Greek state itself funding refugee needs, rather than EU institutions, international organizations, charitable organizations, and others. To date there is no coherent national integration strategy for migrants. Ultimately, a percentage of those who land on Greek shores will remain in the country and their legal status must be addressed. But the bigger hurdle is acceptance of migrants by Greeks and the integration of these newcomers into society—all actions that will ultimately occur at the local level.

Sources

Agence France Presse (AFP). 2019. New Arrivals Push Greek Island Refugee Camp to Bursting Point. AFP, August 31, 2019.

Anagnostou, Dia. 2016. Local Government and Migrant Integration in Greece. Athens: Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy. Available online.

Associated Press (AP). 2019. Greece to Tighten Borders, Speed Asylum-Seeker Deportations. AP, August 31, 2019. Available online.

Cabot, Heath. 2014. On the Doorstep of Europe. Asylum and Citizenship in Greece. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Caponio, Tiziana and Maren Borkert, eds. 2010. The Local Dimension of Migration Policymaking. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Dekker, Rianne, Henrik Emilsson, Berhnard Krieger, and Peter Scholten. (2015). A Local Dimension of Integration Policies? A Comparative Study of Berlin, Malmo, and Rotterdam. International Migration Review. Fall 2015: 1-26.

European Commission. 2018. Managing Migration: EU Financial Support to Greece. Factsheet, April 2018. Available online.

Gropas, Ruby and Anna Triandafyllidou. 2011. Migrants and Political Life in Greece: Between Political Patronage and the Search for Inclusion. South European Politics & Society 17 (1): 45-63.

Hellenic Government. 2010. Kallikratis Law 3852/2010. Updated June 7, 2010. Available online.

Hernandez, Joel. 2016. Refugee Flows to Lesvos: Evolution of a Humanitarian Response. Migration Information Source, January 29, 2016. Available online.

Hooghe, Liesbet and Gary Marks. 2002. Types of Multi-Level Governance. European Integration Online Papers 5 (11). Available online.

International Rescue Committee (IRC). 2016. Learning from Lesbos: Lessons from the IRC’s Early Emergency Response in the Urban Areas of Lesbos between September 2015 and March 2016. London: IRC. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2019. Flow Monitoring: Europe–Arrivals to Greece. Accessed September 2, 2019. Available online.

Lindsay, Frey. 2019. Community Migration Organizations Need More Flexibility and Clarity from EU Funds. Forbes, July 1, 2019. Available online.

New Europe. 2019. EU Remains in Contact with Greece and Turkey as Migration Flow Increases. New Europe, September 4, 2019. Available online.

Nielsen, Nikolaj. 2018. “Integration:” The Missing Factor in New EU Migration Fund. EUobserver, October 23, 2018. Available online.

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR). 2017. Local and Central Government Coordination on the Process of Migrant Integration: Good Practices from Selected OSCE Participating States. OSCE/ODIHR policy study, Warsaw, November 2017. Available online.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 2018. Working Together for Local Integration of Migrants and Refugees in Athens. Paris: OECD. Available online.

Petracou, Electra, Nadina Leivaditi, Giorgos Maris, Maria Margariti, Paraskevi Tsitsaraki, and Angelos Ilias. 2018. Greece – Country Report: Legal and Policy Framework of Migration Governance. Global Migration: Consequences and Responses Working Paper 2018/04, May 2018. Available online.

Rafenberg, Marina. 2019. In Lesbos, Fears of New Migrant Influx Return. AFP, August 31, 2019. Available online.

Scholten, Peter. 2018. Beyond Migrant Integration Policies: Rethinking the Urban Governance of Migration-Related Diversity. Croatan & Comparative Public Administration. (18): 7-29.

UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) Greece. 2019. Aegean Islands Weekly Snapshot, 26 August – 01 September 2019. Available online.