You are here

As Nauru Shows, Asylum Outsourcing Has Unexpected Impacts on Host Communities

Protests at a refugee compound in Nauru. (Photo: Julia Morris)

Limestone pinnacles and mining pits pockmark the 21-square kilometer (8-square mile) island of Nauru, a Pacific nation best known recently for its pivotal role in Australia’s extraterritorial asylum arrangements. A century of phosphate mining momentarily allowed Nauru to achieve the world’s second-highest gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, in 1975, but environmental depletion and near-bankruptcy in the 1990s diminished the industry significantly.

Since then, Nauru’s financial footing has depended on hosting a regional asylum processing and resettlement operation for Australia. On and off since 2001, Australia automatically sent asylum seekers arriving by boat to Nauru or Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island for refugee status determination. If successful in their asylum claims, migrants received refugee visas and basic resettlement support to live and work on the islands. At the peak period from 2013 to 2016, just over 1,200 asylum seekers were in Nauru; most came from the Middle East or South Asia.

In June, the last refugee held by Australia left Nauru, leaving the facility empty for the first time in more than a decade (the facility was closed from 2008 to 2012 as Australia paused its much-criticized extraterritorial processing program). The regional processing center itself is still standing under what the government describes as an “enduring capability” arrangement. Nauru may once again host asylum seekers, depending on the Australian government’s immigration policy directions.

In exchange, the Nauruan government since 2001 has received over AU$5 billion (approximately U.S. $3.3 billion) from Australia, a massive sum for a country with an estimated GDP of less than AU$200 million (approximately U.S. $133 million) as of 2022. Significant amounts of money have also come through less direct channels. Industries responsible for asylum adjudication and the resettlement of refugees in Nauru employed a substantial proportion of the local population in addition to Australian and other foreign employees; in 2021, 15 percent of the island’s local labor force was employed at the regional processing center, and significantly more people worked in ancillary industries. The economy of the 12,000-person island revolved around leasing land, renting cars, providing accommodation, selling goods, and serving cocktails to center-linked personnel. Australia also supported construction of a new hospital, school, courthouse, and road system as development support.

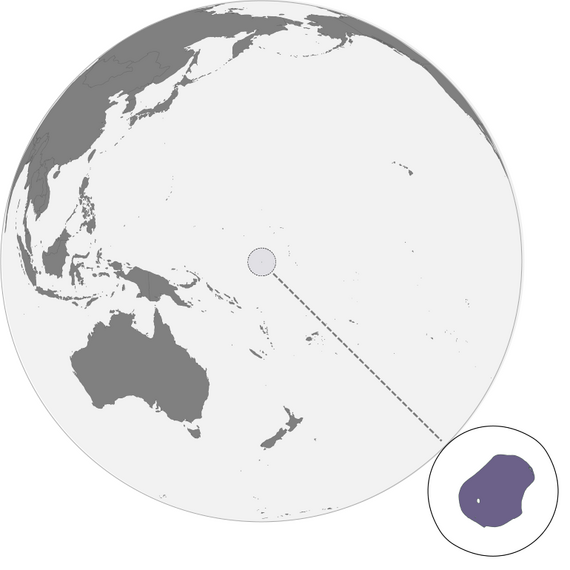

Figure 1. Map of Nauru

The offshore asylum policy played a hugely symbolic role in Australia’s post-9/11 approach to border control, kickstarted with then-Prime Minister John Howard’s 2001 statement, “We will decide who comes to this country and the circumstances in which they come.” This type of arrangement has become a global trend whereby some Western countries outsource asylum to those in the Global South, either by helping fund asylum systems and border control in transit countries or diverting asylum seekers arriving at Western borders. The European Union has provided funding to countries such as Albania, Libya, Niger, Tunisia, and Turkey to encounter asylum seekers before they reach the bloc. Somewhat similarly, the United States has financed the capacity of some Latin American countries to develop asylum adjudication systems and promote livelihood opportunities to encourage migrants to claim asylum regionally. The UK-Rwanda arrangement—under which asylum seekers arriving in the United Kingdom would be redirected to Rwanda to have their claims processed and, if approved, to be granted Rwandan residency—is the highest-profile and most extreme example of the trend. (As of this writing, implementation of the UK-Rwanda policy has been blocked by the courts.)

The impacts on migrants sent to third countries for asylum processing are well documented. In Nauru, many asylum seekers reported extreme mental health challenges, tormented by the inability to move beyond the island. There were suicide attempts and other episodes of extreme self-harm documented at the facility. The reported abuses and mistreatment of asylum seekers in Nauru and elsewhere are not to be taken lightly. But outsourcing asylum has impacts and repercussions for host communities, too, that also deserve scrutiny and have been under-covered.

Since agreeing to the Australia deal, Nauruans have been described by global media organizations and advocacy campaigns as cruel abusers of refugees. Similar framings are also used with other countries that have agreed to outsourced asylum arrangements. Although there are well-founded concerns about the Rwandan government, some media and advocates have stigmatized the entirety of Rwanda as an underdeveloped war zone. And during a short-lived U.S.-Guatemala asylum cooperation agreement, some U.S. activists and media organizations spotlighted the country as a site of extreme human-rights abuse where violence, persecution, and murder were common.

This article describes the impacts of outsourcing asylum on host communities and refugees, based on long-term fieldwork conducted for the author’s book Asylum and Extraction in the Republic of Nauru. Contemporary portrayals of outsourced asylum arrangements often ignore the consequences on local residents for whom the policies may mirror larger historical trends of colonialism and resource extraction.

History of Outsourced Asylum

Systems of preventing access to asylum and outsourcing it have a long history rooted in the governance of migration. For example, in the early 20th century, countries throughout the Americas and British-mandated Palestine used visa restrictions, naval interceptions, island detention centers, and other practices to block arrivals of Jews leaving Europe. After World War I, the Nansen Office and Intergovernmental Committee on Refugees designated groups of Armenians, Greeks, and Russians as refugees via ad hoc policies, moving them between countries. Just a few decades later, as vast numbers of Jewish refugees sought to escape the atrocities of World War II, many European countries refused to provide them sanctuary. Meanwhile, countries as far flung as the Dominican Republic and Ecuador promoted themselves as destinations for Jewish refugees to attract political and economic support.

The 1951 Refugee Convention gave governments the cooperative framework for regulating humanitarian migration in and out of their territory. Its preamble states asylum “may place unduly heavy burdens on certain countries,” which may necessitate “international cooperation,” a phrase which signatories have interpreted as providing for both the expenditures associated with asylum and the physical presence of migrants themselves. Increasingly concerned with the socioeconomic and political costs of asylum, many Western governments began financing refugee camps close to regions of displacement. This approach was designed in part to encourage refugees to stay near their places of origin. These policies combined with other forms of immigration control such as redefining territories’ status for immigration purposes; carrier sanctions on airline, train, and shipping companies; immigration pre-inspections; boat pushbacks; and various forms of coordinated border management.

The practice of financing another country to carry out asylum adjudication and refugee resettlement stems from these methods of border control. Most humanitarian migrants are hosted in countries in the Global South, proximate to conflict or other disaster zones. However, the last 15 years have seen a dramatic increase in Western countries funding the asylum procedures of countries in the Global South. For Refugee Convention signatories, such policies look to reduce the numbers of migrants arriving at and claiming asylum at Western state borders yet attempt to avoid derogating on their international legal responsibilities by still allowing these individuals to seek asylum. In 2023, the Biden administration issued a proposed rule requiring asylum seekers who pass through a third country en route to the U.S.-Mexico border to claim asylum there first or make an appointment at a border post, in some aspects echoing a similar policy from the Trump administration that was blocked by the courts. (A federal court recently ruled against the Biden rule but an appeals court had allowed it to continue operating temporarily as of this writing.) This policy takes a page from the European Union’s playbook. Under the Dublin Regulation, migrants must claim asylum at the first signatory country to which they arrive. To dissuade migrants from getting this far, the bloc finances border enforcement and asylum adjudication in third countries across Central Asia, Eastern Europe, and North Africa, most recently inking a deal with Tunisia in July to tighten its border controls in exchange for 1 billion euros from the European Union. Meanwhile, Australia has pursued a strategy of extra-territorialization, funding border control in South Asian countries and sending intercepted asylum seekers to Pacific Island nations such as Nauru.

Many of these arrangements mimic histories of colonial rule, which often revolved around resource extraction—but in this case, the extraction is of people on the move, as well as of land and resources to limit those movements. Indeed, just like other extractive industries, processing and hosting refugees is promoted as an economic boom to countries in the Global South. As well as financial incentives, host countries are promised a range of benefits such as funding for roads, schools, hospitals, and other infrastructure. In places such as Nauru, these dynamics can echo the ways mining industries gain support among residents and politicians. But just like Nauru’s dwindling phosphate mining industry, these promises belie the broader impacts of outsourcing asylum on local communities, as well as the impermanence of the industry’s economic gains.

Lasting Local Impacts

Due largely to Australia’s asylum arrangement, government revenue in Nauru increased tenfold over the last decade: from AU$30 million in 2011-12 to AU$320 million in 2021-22. The government estimates that money from hosting a regional processing regime accounted for about two-thirds (AU$206 million) of total revenue in 2021-22.

Even as asylum seekers have left, the processing and resettlement contract remains quite lucrative. Now, Australia is funding Nauru to maintain what it has described as an operationally ready regional processing capability, which can be restarted if and when required. The Nauru government is forecasted to receive revenue of AU$133 million for 2023-24.

What Money Does Not Show

Even as this arrangement has been transformational for the country’s economy, Nauruans have suffered damaging consequences. Immense economic disparities exist in how benefits accrued from hosting the asylum operations are distributed. Ultimately, well-connected landowners and political leaders are the ones who have greatly profited. Some residents complained to the author that corruption and greed had overtaken the government. Protests against local politicians were commonplace. Those in power tended to gloss over the destructive effects, instead emphasizing Nauru’s role in “stopping the boats” (an iconic Australian political promise recently adopted by the United Kingdom) and protecting refugees, as well as the local diversity that asylum seekers brought.

Meanwhile, local communities, usually poor and without access to land, were left out. Residents witnessed the diversion of local workforces to the asylum industry, in which they worked as security guards, facility managers, drivers, teachers, and social workers—a trend that Nauruans and Australians described to the author as a brain drain. Typically, this concept characterizes the emigration of well-educated professionals out of the country, but here it represented many Nauruan workers leaving jobs in the government and other public-facing sectors to work for Australian and foreign contractors paying much larger salaries. While remaining in Nauru, their skills were nonetheless diverted to serving foreign interests rather than their own population. This contributed to a dearth of local professionals to administer local policies, particularly in the education and medical fields. The processing center and resettlement compounds where asylum seekers lived became enclaves, isolated from essential sectors of the economy.

Other crucial sectors were left to decay. Often, development aid went unspent because no trained staff were there to ensure money was allocated effectively. Nauru remained reliant on foreign expertise, with almost all institutions led by foreign advisors in managerial positions. High-school dropout rates increased, which locals attributed to easily obtainable low-level employment with refugee contractors. Younger locals dropped out of teacher-training courses because they could easily access jobs within the asylum industry as security guards and drivers. While there is no doubt that the asylum arrangement has brought the country significant wealth, the benefits have limited reach. And as the asylum industry moves on, those who had chosen it over other career paths may find themselves with short-lived gains.

Refugees Welcome?

One of the greatest impacts of the offshoring policy resulted from confining migrants in an unfamiliar location against their will. In 2015, the Nauruan government opened the doors to the processing center where asylum seekers resided, meaning most could come and go throughout the day. Those who received refugee visas lived in compounds around Nauru’s urban fringe. No asylum seeker the author spoke to wanted to be in Nauru, nor expected to be sent there when taking a boat to Australia. Most were from faraway places such as Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, and Vietnam. Many had lived in cosmopolitan hubs, including Jakarta and Tehran. They had no interest in or experience with Pacific Island life, where access to a variety of foods and urban amenities is limited, and where the equatorial heat can be extreme. Nauruans could take a flight to Brisbane or Fiji, but refugees were not allowed to travel beyond the island. These restrictions produced immense claustrophobia among most refugees the author interviewed. Some refugees also feared living in a remote locale that they only knew through media narratives suggesting Nauruan savagery. Many also suffered the aftereffects of trauma, including abuse and economic deprivation in their homelands, compounded by harrowing boat journeys and unknowable futures in Nauru.

For some, these tensions were too much. Self-harm and suicide were common among asylum seekers and refugees, affecting three in ten adults and nearly half of children, according to findings by Australian clinicians. Subject to the highly contentious politics surrounding the asylum arrangement, some also engaged in regular and occasionally violent protests, including self-immolation, self-harm, arson, jumping from roofs, and sewing their lips together.

The Australian government financed small-business startup packages for those receiving refugee status. Two Australian organizations, the Multicultural Development Association and Australian Multicultural Education Services, were contracted to offer job-matching services and employment-searching skills for Nauru. Curry houses, Middle Eastern takeaways, and beauty salons were soon in ample supply. However, the cuisine and services offered by refugees generally appealed to Australians and largely serviced fly-in, fly-out personnel contracted by the asylum industry. Again, the processing center seemed to exist in a bubble apart from the rest of the island’s economic life.

Most refugees told the author they had no desire to integrate. “How can I build a livelihood here for my children?” one refugee from Iran asked. “What am I supposed to do? Deliver Persian takeaway each day to Australian social workers?” Others refused to work, in protest of the asylum policy. Those who did said they were saving for setting up a new life in Australia, holding out hope that the Australian government would change its immigration policy. Nauruan language classes had no uptake and were eventually discontinued. The Australian government later struggled to find Nauruans willing to teach mandatory cultural orientation workshops for refugees.

Local Resentment of Global Narratives

At first, most Nauruans were sympathetic to the asylum seekers. A number strongly disagreed with the asylum arrangement. But many became frustrated by media reports and activist framings that presented them as human-rights abusers. Drawing on colonial tropes of Pacific Islanders as savages, some organizations described Nauru as an “island of despair” and suggested that merely living there was akin to torture. “Look at this stuff they write … They haven’t even been here,” said one Nauruan government worker.

Many Nauruans feared refugees, worrying they would be targeted by high-profile protests to attract media attention. “I don’t pick them up anymore,” a local university administrator commented, pointing at a group of hitchhiking refugees. “If something happens and I crash, who knows what the Australian media will say.” A Nauruan school caterer said, “We don’t know what they might do next. So many of them are desperate to get to Australia, they’ll do anything. We don’t know where they’re coming from. They could take us hostage. Make bombs from phosphate.” Some residents feared migrants were sent to the island because they were security threats, mirroring certain political and media narratives of asylum seekers as potential terrorists. They wondered why the Australian government sent asylum seekers to Nauru instead of housing them in Australia.

Conflicts occasionally occurred between some refugees and Nauruans. Many islanders were frustrated at the socioeconomic disparities produced by Australian investments in the refugee facilities, which housed a well-equipped school, medical center, refectory, and gym, all with internet access and air conditioning, and where imported fresh foods were in regular supply. These sorts of amenities were much greater than those to which the majority of Nauruans had access. Accusations also circulated of refugees trespassing on private property and picking coconuts from private groves, which compounded the anger of many locals. A small minority of refugees also goaded Nauruans to attack them, knowing that Australian press attention might support their case. “Well, what else can we do to get there?” commented a younger refugee, emphasizing asylum seekers’ desperation. “‘Be nice to the refugees,’ the government’s always saying this,” said a local school caterer. “‘Don’t touch them, they’ll just contact the Australian media and you know what they’ll say.’ But why do they have to be nasty about us?” This is not to justify possible incidents, but to emphasize that conflicts were a result of the Australian government’s policy.

Conflicts also occurred among asylum seekers and refugees. Some were the effects of confining people, a small number with histories of violence, in a carceral environment. Ethnic frictions were produced by combining groups with pre-existing animosities on a small island. Other aggressions were connected to the psychological burden of the outsourced asylum arrangement, where living up against one another for prolonged periods resulted in extreme tensions.

Still, some refugees and locals formed powerful solidarities. The Australian government funded an elaborate music technology set-up with computers, recording equipment, and music editing software to encourage the integration of young Nauruans and refugees. However, instead of writing songs about refugee integration in Nauru, a group of Nauruan and Afghan teenagers rapped about their joint hopes for refugees to be resettled in Australia. Australian authorities prohibited these music videos from being made public. The projects would have been embarrassing, exposing just how much effort went into sustaining the asylum arrangement despite the desires of many locals and migrants alike.

Local Perspectives

Popular portrayals of asylum seekers as either victims or terrorists—and host countries as either saviors or abusers—obscure the true impacts of outsourced asylum regimes. In reality, migrants and locals in Nauru both experienced negative effects from the asylum arrangement. Meanwhile, successive Australian politicians have gained political capital from the spectacle of the island as a remote, hostile place. It is precisely because Nauru and other countries are represented in derogatory terms that outsourced asylum practices succeed as a deterrence threat. These representations erase local perspectives and fail to provide nuance to local impacts.

Now, Nauru is facing a future without refugees. Many Nauruans question what lies ahead for the island’s economy. Some point out that the asylum arrangement is not a sustainable development model, but has created an Australia-centric political economy reliant on foreign contractors. The winding down of the asylum policy will make it difficult to sustain the local benefits of improved welfare and wages. Like Nauru, many regions where Western countries have financed outsourced asylum projects are reliant on foreign aid, following histories of colonial extraction. The asylum industry is presented to local communities as an economic boon with profit-making opportunities, while arriving asylum seekers are also often described as a new labor force to support economic development. But these policies almost always go against the aspirations of migrants, who tend to be disinterested in integrating locally. And they often fail to incorporate the wishes of local residents or address their concerns.

The European Union, United Kingdom, and United States have all experimented with systems that in one way or another offer economic and development incentives to countries in the Global South in order to secure their assistance on asylum-related matters. But policymakers at both ends must ask themselves: Is it worth the money to send asylum seekers to third countries? What sort of impacts might third-country asylum have on host communities?

Research shows the benefits of alternative strategies such as expanding legal labor migration and supporting local-led development initiatives in migrants’ origin countries. Not only do these practices support livelihoods, but they can also benefit the economies of sending and receiving countries in the long term. Meanwhile, the stakes are high for humanitarian migrants subject to third-country asylum. “You can’t plan, you don’t know what the future will be. It’s hard to keep on going in that kind of situation,” a young Iranian refugee in Nauru confided to the author. “I feel like I can’t be useful in any way. I’m just wasting away here, without any idea of what my goals can be.”

Sources

Amarasena, Lahiru et al. 2022. Offshore Detention: Cross-Sectional Analysis of the Health of Children and Young People Seeking Asylum in Australia. Archives of Disease in Childhood 108 (3): 185-91. Available online.

Amnesty International. 2016. Island of Despair: Australia’s “Processing” of Refugees on Nauru. London: Amnesty International. Available online.

Bever, Lindsey. 2016. ‘Cruel in the Extreme’: Australia Accused of Ignoring ‘Appalling’ Abuse of Refugees. The Washington Post, August 3, 2016. Available online.

Endres de Oliveira, Pauline and Nikolas Feith Tan. 2023. External Processing: A Tool to Expand Protection or Further Restrict Territorial Asylum? Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Available online.

Gatrell, Peter. 2013. The Making of the Modern Refugee. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hedrick, Kyli, Gregory Armstrong, Guy Coffey, and Rohan Borschmann. 2019. Self-Harm in the Australian Asylum Seeker Population: A National Records-Based Study. SSM – Population Health 8: 100452. Available online.

Koziol, Michael. 2016. 'Island of Despair': Australia Intentionally Torturing Refugees on Nauru, Says Major Amnesty International Report. The Sydney Morning Herald, October 18, 2016. Available online.

Morris, Julia. 2023. Asylum and Extraction in the Republic of Nauru. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

National Public Radio (NPR). 2016. Claims Probed of Brutal Conditions for Refugees on Island of Nauru. NPR News, August 11, 2016. Available online.

Republic of Nauru, Department of Finance. N.d. Budget Reports. Accessed July 6, 2023. Available online.

SBS News. 2014. We Will F*****g Kill You: Beaten Nauru Refugees Fear for Their Lives. SBS News, October 29, 20214. Available online.

Vargas-Silva, Carlos and Madeleine Sumption. 2023. The Labour Market Effects of Immigration. The Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, March 24, 2023. Available online.