You are here

Once Homogenous, Tiny Iceland Opens Its Doors to Immigrants

Fishing boats in the port of Húsavík, Iceland. (Photo: Nick Sarebi)

A small, isolated country in the north Atlantic, Iceland is known for its unique landscape of volcanoes, glaciers, and waterfalls. It experienced a spectacular banking crisis in 2008 and an equally spectacular eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in 2010, which temporarily brought European air travel to a halt. Due to its geographic location, the population remained isolated and quite homogeneous until recently. As late as the mid-1990s, foreigners who acquired Icelandic citizenship were required to adopt an Icelandic name. However, strong economic growth over the past several decades and a booming tourism sector more recently have drawn greater numbers of immigrants to the island nation—bringing increased diversity to the once-homogeneous society.

This article traces the history of emigration from and immigration to Iceland, focusing on the growth of the immigrant population over the last several decades, the diversification of origins, and various government responses to these changes as Iceland tries to balance economic growth with preserving its culture and language.

A Small, Homogenous Population Opens Up

Over the past half century, Iceland has experienced substantial economic growth, propelling the country from one of the poorest in Europe to among the richest. It achieved this through a series of free-market reforms combined with high levels of government intervention.

Traditionally, Iceland’s economy was based on fishing, fish processing, and related industries. These sectors remain important, especially for exports, and create a demand for foreign labor. The economy has since diversified and the service sector, including tourism, now accounts for about 60 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). The country lacks natural resources such as oil, coal, and minerals but has abundant hydroelectric power, which it has used to construct several aluminum plants. One large plant in Reyðarfjörður, in eastern Iceland, started production in 2008 after being built with considerable immigrant labor.

In 2008, Iceland’s three largest commercial banks defaulted. This resulted in an economic contraction, a rise in unemployment, and political instability. Owing to a series of internal and external measures, the country recovered rapidly, and GDP began to grow again in 2011.

Today, the economy remains strong and unemployment enviably low, perpetuating the demand for foreign labor. As those in other Western countries, immigrants in Iceland are over-represented in low-skilled occupations, including sectors such as manufacturing, fish processing, care and cleaning, lodging, and food and retail service.

From Emigration to Immigration

Being a small, geographically isolated country, Iceland (population of roughly 338,000 at the beginning of 2017) has a long history of emigration. Icelanders emigrate permanently in difficult economic times and temporarily to gain education or skills. Based on return migration data, 80 percent of Icelandic citizens who left from 1986 to 2008 moved back after an average stay abroad of 2.4 years.

Many returnees gained education or experience while overseas, returning with skills that can be useful to Icelandic society and economy. Most presumably spoke Icelandic and had family or other social ties on the island, and as these returns made up the bulk of arrivals, there was little need for laws on foreigners or integration policies.

However, returning Icelanders have comprised a falling share of in-migration in recent decades, from 73 percent in 1986 to 29 percent in 2008. That year, more than 70 percent of arrivals were immigrants who likely did not speak Icelandic, had few ties to the country, and would take longer to integrate socially and economically.

In 1990, the foreign-born share of the total population was roughly 4 percent. With the recent increase in immigration, it rose to about 11 percent in 2017. Meanwhile, the share of residents who are not Icelandic citizens has grown from less than 2 percent in 1996 to 9 percent in 2017. The uptick has caused a rethinking of immigration and integration policy.

Migration Booms and Busts

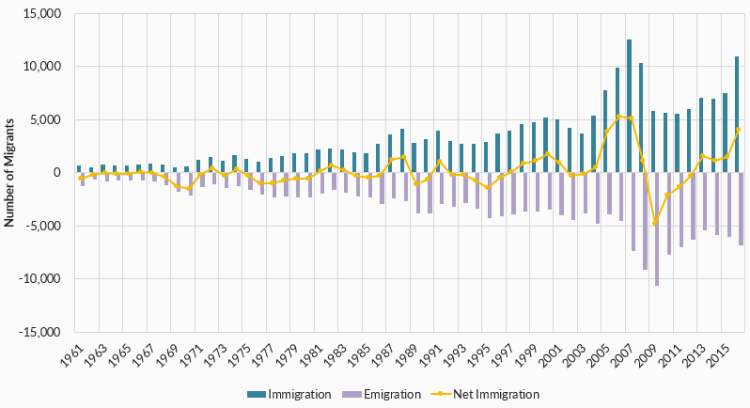

A deeper dive into the data shows that since 1960, Iceland has vacillated between net emigration and net immigration. From 1960 to 1996, there was a net loss of some 9,300 people leaving the country over the period (see Figure 1). This changed during the boom years of 1997 to 2008, with a relatively large net inflow of 20,300, followed by a net outflow of 8,700 between 2009 and 2012, in the wake of the banking crisis. Net migration became positive again in 2013 and in 2016 the number of new arrivals surpassed 10,000 annually, approaching pre-crisis levels.

The volume of new arrivals increased from slightly more than 1 percent of the total population in the early 1990s—which was balanced by roughly equal outflows, largely native Icelanders moving abroad for a period and then returning—to more than 4 percent of the roughly 300,000 population at the peak of immigration in 2007.

Figure 1. Immigration, Emigration, and Net Migration in Iceland, 1960–2016

Source: Statistics Iceland, “External Migration by Sex and Citizenship 1961-2016,” accessed April 16, 2018, available online.

Icelandic citizens and noncitizens responded differently to the period of economic expansion prior to and following the 2008 banking crisis. From 2004 to 2007, most of the net immigration was driven by noncitizens immigrating, with smaller numbers of Icelandic citizens emigrating. Following the crisis, Icelandic citizens responded by leaving, more so than noncitizens. Since 2013, a net 2,200 Icelandic citizens have moved away and a net 10,400 noncitizens have moved in. This development has resulted in a historically high number and share of noncitizens in Iceland.

Until 2003, the gender pattern of both immigration and emigration was fairly balanced between men and women. However, during the economic expansion prior to the banking crisis the balance began to be skewed, with sectors such as construction employing more men than women. From 2003 to 2007, some 10,300 men immigrated, more than twice the 4,400 women. Further, following the banking collapse, from 2008 to 2012, 6,700 males emigrated but only 900 females. As the Icelandic economy expands, this trend is repeating itself: In 2016, 60 percent of immigrants to the island were men.

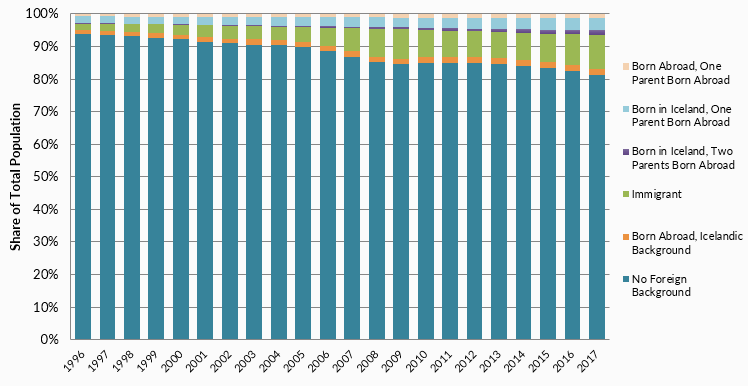

In 1996, 95 percent of Iceland’s population had either no foreign background or had been born aboard with Icelandic parents (see Figure 2). Thus, two decades ago Iceland was still a quite homogenous society. Ten years later, those with an Icelandic background had declined to 90 percent and the immigrant share had increased to 5.6 percent.

Figure 2. Icelandic Population by Background, 1996–2017

Source: Statistics Iceland, “Population by Origin, Sex, Age, and Citizenship 1996-2017,” accessed April 16, 2018, available online.

Most recently, in 2017, those with an Icelandic background had declined to 83 percent of the total population. The foreign-born share is now nearly 11 percent, and in total, some 17 percent of the Icelandic population has an immigrant background.

Increasing Diversity of Origin Countries

Over the years, immigration to Iceland has also diversified, owing in part to the expansion of the European Union. Though Iceland is not a member of the European Union, it belongs to the European Economic Area, which allows free cross-border labor movement with EU Member States.

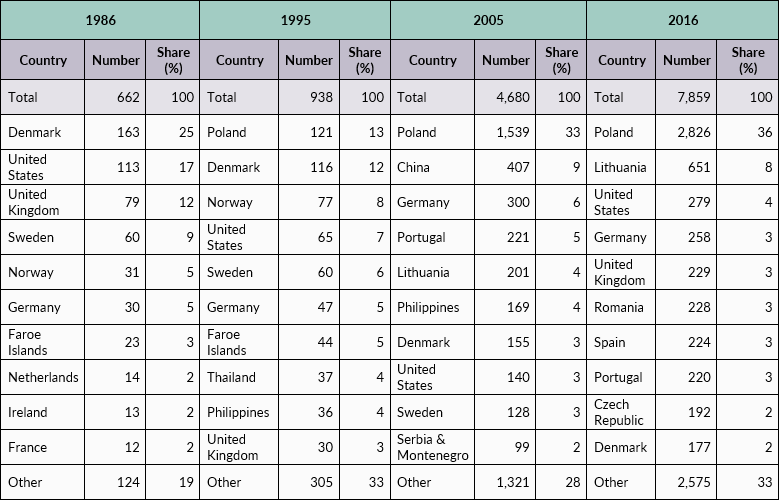

In 1986, Denmark, the United States, the United Kingdom, Sweden, and Norway, were the top origin countries, making up 70 percent of arrivals (excluding returning Icelandic citizens). Citizens of Nordic countries have always enjoyed privileged status when migrating to or applying for citizenship in Iceland. Flows from other regions were still quite small, including from the new EU Member States.

Table 1. Top Ten Origin Countries of Immigrant Arrivals to Iceland, 1986–2016

Source: Statistics Iceland, “External Migration by Sex, Age, and Citizenship 1986-2016,” accessed April 16, 2018, available online.

A decade later, in 1995, origin countries had become more diverse. Polish citizens were now the largest group, exceeding those from Denmark. In 2005, the first full year after the EU accession of ten countries (including Poland), new arrivals were more than five times what they were in 1995 and Polish citizens made up one-third of all arrivals. In 2016, Poland remained the top country of origin.

Citizens of the non-Nordic EU countries now make up most immigration to Iceland. In the last few years, the Icelandic economy has grown rapidly, with considerable investment in projects such as an aluminum smelter in eastern Iceland. This created demand for labor that was met by workers from the new EU Member States. Nearly 13,800 Polish citizens lived in Iceland as of 2017, comprising about 4 percent of the total population.

During fieldwork conducted by the authors in the Ísafjörður municipality in northwest Iceland in the fall of 2016, the role and situation of Polish citizens was evident. The economy of the region is based on fishing, fish processing, and equipment manufacturing for the seafood industry. Most workers in the processing plants were Polish and plant owners described these immigrants as vital to the continued operation of the plants. Polish and other immigrant groups work in both low-skilled occupations such as fish processing and higher-skilled jobs such as welding.

Workers at the Fish Processing Plant Íslandssaga Suðureyri

Most workers at the plant are immigrants and the company would not thrive without them.

Photo: Hjördís Rut Sigurjonsdottir

The number of Polish workers and family members has reached such a level that a separate Polish food store has opened, adjacent to the main grocery store in town. Many Poles view their stay as temporary and thus do not make the effort to learn the rather difficult Icelandic language beyond a very basic level. As a result, both immigrants and their children, who make up 20 percent of students in the municipality, end up segregated from the Icelandic population. There have been efforts recently to encourage integration through programs that teach Icelandic as a second language.

Polish Goods Store in Ísafjörður

Photo: Hjördis Rut Sigurjonsdottir

Evolution of Icelandic Migration Policy

As more foreigners move to Iceland, the government has started adjusting its immigration policies accordingly. For centuries, Iceland was under Danish rule, thus laws adopted by Denmark had equal force in Iceland. This included the first nationality law adopted in 1898 which was based on the jus sanguinis principle—citizenship by blood—with some possibility to acquire citizenship by applying to Parliament, which reviews citizenship applications twice a year.

In 1944, Iceland became an independent republic, and in 1952 introduced a citizenship law that remains in force today with a few amendments. Given the importance of the Icelandic language and culture to national identity, the law required foreigners acquiring Icelandic citizenship to “Icelandicize” their names, either by dropping or modifying them to become Icelandic. Underlying this provision was a fear that an influx of foreigners could threaten long-established customs.

Parliament abolished the Icelandic name requirement in 1996, though new citizens must still demonstrate basic knowledge of Icelandic. The Citizenship Act of 1952 also barred dual citizenship, until a 2003 amendment dropped this prohibition. The naturalization process was simplified in 2007.

Making Icelanders

Like other immigrant-receiving countries, Iceland has had to grapple with accommodating these newcomers. A report on immigrant integration from the Ministry of Welfare gives an idea of how the concepts of assimilation and integration are understood and defined by Icelandic authorities. According to the report, assimilation (samlögun) occurs when immigrants and other ethnic minorities leave their original culture and language behind and adopt those of their new country. This may manifest in different ways, for example by redefining their nationality or by learning the new language without maintaining their native tongue. Meanwhile, integration (samþætting/aðlögun) is the preferred policy, when minorities try to dedicate themselves to their new country’s dominant culture while simultaneously maintaining their own culture and language.

The Icelandic government first enacted an explicit integration policy in 2007, which focused on democracy, human rights, social responsibility, and individual freedom. The policy aims to ensure that all inhabitants of Iceland enjoy equal opportunities and contribute to society. It has not been renewed since then, though two action plans have been implemented. The Association of Local Authorities in Iceland launched a special immigration policy in 2009, which aims to protect immigrants’ rights and teach them about their rights and obligations. The policy’s goal is to give immigrants the opportunity to be independent and active members of society, and to be on equal footing with native Icelanders.

Few people worldwide speak Icelandic due to the country’s small population. However, Icelanders take pride in their language as a guardian of Icelandic history and culture, and as a symbol of national unification. Further, it is the key to communication and participation in society. As a result, the government has placed significant emphasis on conserving the language, evident in the 2007 immigrant integration policy. It is regarded as important for immigrants to have comprehensive language support to speed up their integration.

In response to the increased interest in migration to Iceland in recent years, Parliament passed a new law on foreigners in June 2016, after extensively reviewing the previous law from 2002. It came into force in early 2017 and included, among other things, simpler application processes to speed up procedures and clarify ambiguities, equipping the system to deal with the increased number of applicants. According to the Ministry of the Interior, the main goals of the legislation were to increase economic competitiveness, protect the rights of humanitarian migrants, and bring the country in line with EU laws.

As an island on the periphery of Europe, Iceland receives a rather small but not insignificant number of asylum seekers and refugees. Asylum applications increased from just 35 in 2009 to 1,095 in 2017. In the last two years, most asylum seekers came from Albania, Macedonia, and Georgia, and were largely rejected on the grounds that these countries are considered “safe” and their citizens not in need of humanitarian protection. Further, Iceland often uses the EU Dublin Regulation to send asylum seekers back to the first EU Member State they entered. In 2016, just 11 percent of applications were accepted. A limited number of refugees are also resettled in Iceland every year.

Iceland Is No Longer a Secret

Iceland has made a strong recovery from the financial crisis and currently enjoys strong economic conditions overall, accentuated by rapid growth in the tourism sector over the last decade. The tourism industry rather cleverly used the 2010 volcanic eruption to promote the country as an exotic place to visit. Overnight stays nearly tripled from 2010 to 2017—from 3 million to almost 9 million—and tourism’s share of GDP grew from less than 4 percent in 2009 to roughly 8 percent in 2016. The surge in visitors has among other things strained the local housing market, since many landlords choose to rent their apartments to tourists rather than long-term tenants. The housing shortage tends to affect immigrants even more so than that the native population, as they are most likely to rent than own a home.

However, with the demand for immigrant labor likely to continue in the coming decades, it seems Iceland’s days as a country of net emigration are behind it. Three different demographic scenarios all project net migration into Iceland to be positive over the next 50 years, and as in other countries, an increase in Iceland’s foreign-born population will probably give rise to further migration. Iceland is no longer a secret, and among the people coming in large numbers are smaller—but significant—numbers who will stay, bringing new challenges and opportunities for the tiny country moving forward.

This article is adapted from research conducted for the project Polar Peoples: Past, Present, and Future, supported by a grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Arctic Social Sciences Program (award number PLR-1418272).

Sources

Association of Local Authorities. 2009. Stefnumótun Sambands íslenskra sveitarfélaga í málefnum innflytjenda (Immigration Policy of the Association of Local Authorities). Reykjavík, Iceland: Association of Local Authorities. Available online.

Greve Harbo, Lisbeth, Timothy Heleniak, and Åsa Ström Hildestrand, eds. 2017. From Migrants to Workers: Regional and Local Practices on Integration of Labour Migrants and Refugees in Rural Areas in the Nordic Countries. Stockholm: Nordregio. Available online.

Grunfelder, Julien, Linus Rispling, and Gustaf Norlén. 2018. State of the Nordic Region 2018. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers. Available online.

Heleniak, Timothy. 2018. From Migrants to Workers: International Migration Trends in the Nordic Countries. Stockholm: Nordregio. Available online.

Heleniak, Timothy, Lisbeth Greve Harbo, Sandra Oliveira e Costa, Hjördís Rut Sigurjónsdóttir, Nelli Mikkola, and Leneisja Jungsberg. 2016. From Migrants to Workers: Immigration and Integration at the Local Level in the Nordic Countries. Stockholm: Nordregio. Available online.

Iceland Directorate of Immigration. 2018. 38 Irish People Provided Protection during the Year. Updated January 18, 2018. Available online.

Iceland Ministry of Welfare. 2005. Skýrsla nefndar um aðlögun innflytjenda að íslensku samfélagi (Report of the Committee on Integration of Immigrants to Icelandic Society). Reykjavik, Iceland: Ministry of Welfare. Available online.

---. 2007. Stefna ríkisstjórnarinnar um aðlögun innflytjenda (Government Policy in Immigration Integration). Reykjavik, Iceland: Ministry of Welfare. Available online.

Jóhannesson, Gudni Th., Gunnar Thór Pétursson, and Thorbjörn Björnsson. 2013. Country Report: Iceland. Fiesole, Italy: European University Institute. Available online.

Multicultural and Information Centre (MCC). 2016. Ný útlendingalög samþykkt á Alþingi (A New Foreign Law Passed in Parliament). MCC, June 3, 2016. Available online.

Statistics Iceland. N.d. External Migration by Sex, Age, and Citizenship 1986-2016. Accessed April 16, 2018. Available online.

---. N.d. External Migration by Sex and Citizenship 1961-2016. Accessed April 16, 2018. Available online.

---. N.d. Population by Origin, Sex, Age, and Citizenship 1996-2017. Accessed April 16, 2018. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2016. Rising to the Challenge: Improving the Asylum Procedure in Iceland. Stockholm: UNHCR. Available online.