You are here

The Philippines’ Landmark Labor Export and Development Policy Enters the Next Generation

Returning Filipino migrant workers. (Photo: IOM/Ray Leyesa)

As the Philippines marks the 50th year of its labor export program and emerges from a global pandemic that chilled migration in unprecedented ways, the country is doubling down on its ambitions to serve as a provider of workers to the world. Emigration has been central to the Philippines’ economic growth since the 1974 Labor Code (Presidential Decree 442), which contained provisions regulating and encouraging the migration of laborers. Since then, millions of Filipino workers have sent back billions of dollars in remittances each year, creating a feedback loop in which emigration has spurred development, which in turn has made international migration seem all the more attractive.

At least 1 million overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) were newly deployed or redeployed every year from 2006 through 2019, a figure that increased to an average of 1.9 million during the 2016-19 period. The COVID-19 pandemic marked a sharp turning point. Only about 550,000 OFWs were deployed in 2020, rising slightly to 676,000 in 2021. Labor migration was tested like never before during the global public health crisis, which chilled international and internal movements worldwide and threatened the notion of emigration as a development strategy.

In This Article:

More than 2 million OFWs returned to the country during the pandemic—sometimes by choice and other times by force—and many wrestled with the possibility of a future without emigration. The government faced challenges handling all these returnees, and the economy was affected by job losses and the shutdown of recruitment as foreign labor markets closed.

It could be fairly said that the Philippines’ migration management system has now returned to pre-pandemic mode. A UN Human Rights Commission report in March 2023 concluded the Philippine government was able to handle the social protection needs of OFWs and their families, especially during the pandemic. The protection of migrants, which has been the mandate of a number of Philippine agencies for decades, had become fully institutionalized. This became clear as the government addressed crisis situations affecting migrant workers even as the pandemic eased. For instance, a transnational cryptocurrency scam in some Southeast Asian countries led to the rescue and repatriation of OFWs in Cambodia, Myanmar, and Thailand. And conflicts in Sudan and in Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories led to more repatriations of OFWs from those states.

Now that the world has fully reopened, Filipino emigration has begun to regain its bearings, albeit with new challenges including bilateral labor disputes and concerns about hollowing out the Philippines’ domestic health-care sector. More than 1.2 million OFWs were deployed in 2022, more than double the figure in 2020.

Perhaps the clearest sign that the government remains committed to staying the course is the new Department of Migrant Workers (DMW), christened amid a new government under President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the son and namesake of the leader who oversaw creation and implementation of the 1974 law. The government’s national development plan mandates providing social protection to OFWs and maximizing using remittances sent back by overseas Filipinos and others for development.

This article reviews trends surrounding international migration and economic development in the Philippines, 50 years after the labor export and development policy was created.

A Sharp Contraction Amid the Pandemic

The Philippines relies on international migration as an economic engine and source for jobs. An estimated 10 million Filipino emigrants live in more than 200 countries, many in temporary and irregular statuses.

During the pandemic, government agencies and civil-society groups pivoted to assisting with return migration and reintegration. As international borders closed, returnees arrived in droves, some returning under their own steam and others forced to leave their country of work. Virtually the entire government during that time focused on ensuring returnees’ safe return, their adherence to public-health protocols, and transport to their origin communities. The DMW also set up a 24/7 operations post and a repatriation command center to assist stranded OFWs.

In 2021 and 2022, approximately 463,000 land- and sea-based OFWs were repatriated through so-called sweeper flights and return ship voyages courtesy of the Department of Foreign Affairs. The rest returned on their own through available flights when borders re-opened. The government provided hotels for quarantine and medical treatment for nearly 43,000 COVID-19-positive returnees. The Overseas Workers Welfare Administration (OWWA), the country’s migrant welfare agency, reportedly spent P23 billion (U.S. $418.2 million) for returnees’ repatriation and quarantine during the first two years of the pandemic.

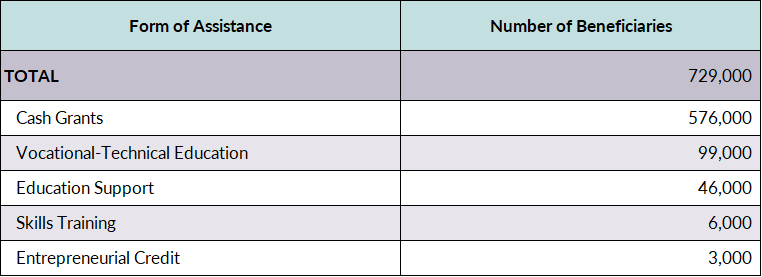

With OFWs earning little to no income during this time, the government handed out cash grants of P10,000 (U.S. $200) to hundreds of thousands of OFWs—including both returnees and those who stayed in host countries—costing in total nearly P5.3 billion (U.S. $95.5 million). Thousands more benefitted from government entrepreneurial loans, financial support, scholarships, and skills training. In all, nearly 729,000 OFWs received some form of government support in the first two years of the pandemic (see Table 1).

Table 1. Economic Reintegration Assistance Provided by the Philippine Government to Overseas Filipino Workers, 2020-22*

* Data cover the two-year period after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, from March 2020 to March 2022.

Source: Alvin P. Ang, Marie Carroline T. Magante, Maria Isabella V. Militante, and Jeremaiah M. Opiniano, Post-Pandemic Reintegration Efforts for Overseas Filipino Workers: What Prospects Abound? (Potsdam: Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom, 2023), available online.

Impact on Migration and Development

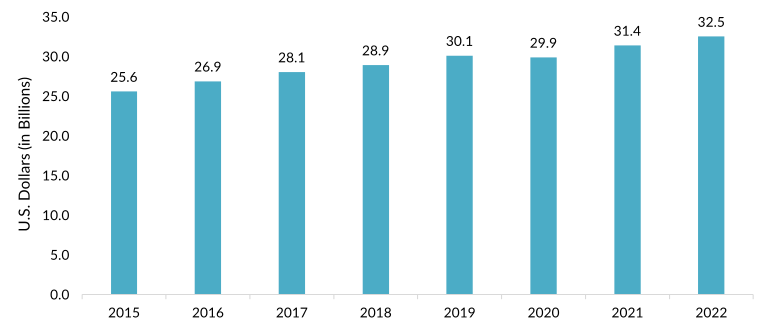

Cash remittances from overseas Filipinos and others became a national worry in 2020, especially since multiple countries underwent economic recessions. Surprisingly, however, cash remittances declined by less than 1 percent between 2019 and 2020, from U.S. $30.1 billion to $29.9 billion, then rebounded to historic annual highs in 2021 ($31.4 billion) and 2022 ($32.5 billion; see Figure 1). Digital remittance channels became a preferred mode of transmission for locked-down migrant workers.

Figure 1. Cash Remittances to the Philippines, 2015-22

Source: Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, “Personal Remittances Reach a New Record High in December 2022; Full-Year Level of US$36.1 Billion Highest to Date,” (press release, February 15, 2023), available online.

Still, the huge numbers of Filipinos displaced from work contributed to widespread economic distress. The country entered a deep recession in 2020 and its economy contracted by more than 9 percent.

Some host countries scouted for foreign labor during the pandemic, especially in the health-care sector, and often turned to the Philippines. Germany sought nurses from the Philippines even as Manila capped the deployment of these health-care workers during the pandemic, first at 5,000 and then 7,500, to safeguard the Philippines’ health-care system. South Korea in 2021 began allowing Filipinos and other migrants to arrive through its Employment Permit System. And many other countries made similar moves, especially as vaccines became available.

Returning to Normal and Rebuilding for the Future?

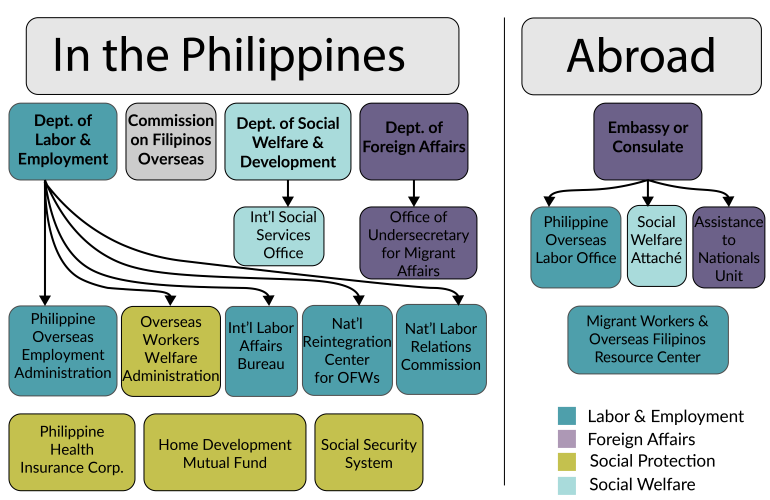

Even as the government and civil society assisted returnees in significant ways, persistent migrant worker-related issues became evident. In December 2021, then-President Rodrigo Duterte signed Republic Act 11641, establishing the DMW as a merger of the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) and other migration-related offices that had previously been under either the Department of Labor and Employment or the Department of Foreign Affairs (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Structure of the Former Philippine Migration Management Bureaucracy, Pre-2023

Source: Jeremaiah M. Opiniano and C.A. Yap, “A Generation of Crisis-Responsive Reintegration in Migration Management: Reflections from the Philippines,” in Return Migration and Crises in Emerging Market Economies, ed. J. Yeo (London: Palgrave MacMillan, forthcoming).

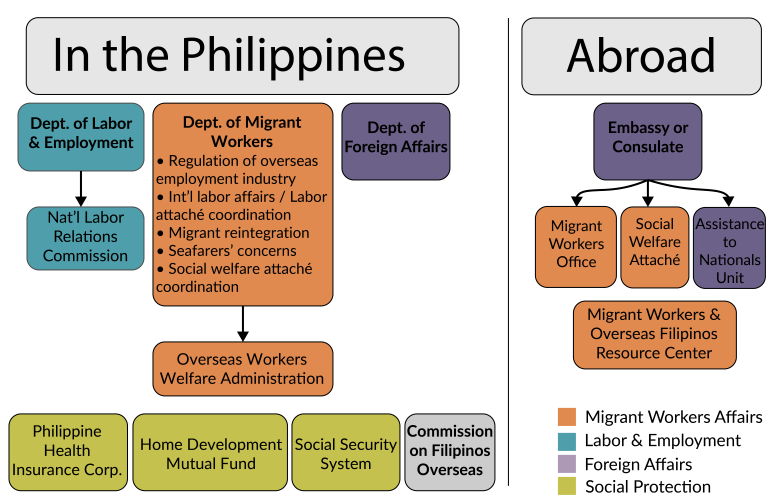

The DMW was created in hopes of addressing coordination failures by various agencies assisting OFWs, in large part by streamlining the migration management bureaucracy (see Figure 3). For example, an illegally recruited returning OFW who was seeking financial assistance could previously have received similar services from OWWA, the Department of Social Welfare and Development, or the National Reintegration Center for OFWs (NRCO).

Now that the DMW has become fully operational, the Philippines is testing a new model to protect migrant workers under this streamlined bureaucracy. (The Department of Foreign Affairs is also integral to this management.) Among its many responsibilities, the DMW handles migrant reintegration, and its NRCO is set to launch a broader set of programs on full-cycle reintegration for returnees including providing reintegration services beginning with the migrant worker’s first overseas departure and continuing until their permanent return.

Figure 3. Structure of the New Philippine Migration Management Bureaucracy, 2023

Source: Opiniano and Yap, “A Generation of Crisis-Responsive Reintegration in Migration Management: Reflections from the Philippines.”

Retooling the System

The creation of the DMW underscored the Philippines’ reliance on international migration and remittances—which comprised about 9 percent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2023—to drive economic growth. Even as domestic unemployment has returned below 5 percent, after hitting a high of more than 17 percent in 2020, workers have ached to return overseas and secure the higher wages available abroad. OFWs also have been eager to recoup lost income, especially if they depleted their savings during the pandemic. After shrinkage in 2020, annual GDP growth reached more than 7 percent in 2022, in part due to the resumption of labor migration. This may not be a surprise, given the dire straits of the first year of the pandemic, when central bank officials were desperate for Filipinos abroad to send money.

For OFWs who continue to return, whether by choice, end of contract, or for various other reasons, the government has moved on from its pandemic-era footing. OWWA in May 2022 ended the provision of assistance with quarantine, accommodation, and transportation that had begun two years earlier.

New Government, Same Approach?

The Philippines’ new government has several echoes of the past. Most obviously, there is the link between Marcos Jr. and his father. Also, upon assuming the presidency in July 2022, Marcos Jr. appointed as the first DMW secretary Susan Ople, the daughter of Marcos Sr.’s Labor Minister Blas Ople, who was known as the father of overseas employment for his role in crafting the 1974 Labor Code.

Within the first six months of the younger Marcos’s presidency, the government wrote a new Philippine Development Plan, covering 2023 to 2028, which included overseas Filipinos under the ambit of social protection. The commitment was actualized by the Philippine government's provision of assistance to returnees during the pandemic, as well as the ongoing social protection measures for OFWs in crisis situations such as the conflicts in Sudan and Israel and the occupied territories. Usual operations continued, including predeparture and postarrival orientations; regulating recruitment agencies; reintegration; and economic services for OFWs, their families, and their children.

Familiar Challenges Rear Their Heads

OFWs and other overseas Filipinos reside in a range of countries, and over the years many have found themselves abused, harassed, or in other ways exploited. Present-day migration management, which includes a focus on the recruitment industry and on conditions for OFWs at destination, is a product of these decades of migrants’ harrowing experiences, which have included deaths and executions, evacuations from wars and other disasters, and attacks by pirates. Many Filipino workers continue to face grave threats. In the March 2023 UN report, the Philippine government acknowledged assisting the voluntary repatriation of about 28,000 migrants since 2018, including some with mental health concerns, children abroad facing risks, and overseas trafficking victims. In six Asian and Middle Eastern countries (Hong Kong, Kuwait, Malaysia, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates), government attachés at embassies assisted nearly 51,000 distressed OFWs (mostly women) from 2020 through 2022. During that same three-year period, officials based in the Philippines assisted some 12,000 distressed OFWs and their family members, as well as nearly 3,000 distressed returning OFWs, and around 3,500 overseas trafficking victims. Meanwhile, approximately 27,000 deployed OFWs benefited from social welfare services provided by the Philippines. While some incidents were certainly a response to the pandemic, Filipino workers abroad clearly continue to face vulnerabilities.

One nagging problem is illegal recruitment. From 2018 to 2022, the Philippines’ Office of the Court Administrator filed 2,300 cases for illegal recruitment (a crime punishable under the Philippines’ Migrant Workers Act) and decided on more than 2,000 cases (there are no publicly available data on outcomes). The government in 2013 created a conciliation-mediation mechanism for OFWs aggrieved about a range of issues, called the Single-Entry Approach. Migrants have also faced dangerous situations while working without authorization, in the black market, and in other situations.

Kuwait, home to an estimated 753,000 total migrant domestic workers (406,000 of whom are female), is a complicated destination country. In 2018, after the gruesome murder of Filipina domestic worker Joanna Demafelis by her employers, the Philippines banned the deployment of domestic workers to Kuwait. Subsequent negotiations led to a lifting of the ban in 2021 and a bilateral labor agreement between the two countries, one of 42 such accords that existed as of this writing. The Philippines reinstituted the ban on domestic houseworkers going to Kuwait in 2023, after the death of another female domestic worker, Jullebee Ranara. That case prompted a review of the 2018 agreement and spurred Kuwait in May to stop issuing visas for all Filipino migrants. The ongoing dispute is Manila's latest test case for asserting protections for Filipino workers.

There have also been triumphs for migration-related diplomacy, such as with Saudi Arabia. More than 189,000 Filipino workers were deployed to the kingdom in 2019, but in 2021 and 2022 the Philippines banned worker deployments there because of claims of unpaid wages by some 10,000 Filipinos working for Saudi construction firms that went bankrupt in 2015 and 2016, as well as rising issues affecting domestic workers. The Saudi government agreed to pay those individuals their wages and create additional safeguards, leading deployments to resume.

The Philippines is also capitalizing on Riyadh’s labor reforms to press for better terms for OFWs. For example, a Saudi green card (or premium residency card) now allows foreign workers to enter Saudi Arabia without a foreign sponsor, a major step towards reforming the kafala system that ties a foreign worker to their local employer sponsor.

Still, longstanding labor- and welfare-related cases have persisted in countries worldwide. Among these are nonpayment of wages, which migrant advocates describe as wage theft and say intensified during the pandemic.

As a sign of its advocacy on OFWs’ behalf, the Philippine government has tried to ensure workers’ overseas employment. In early 2023 it made moves to assist seafarers—who have found skills training and upgrading to be expensive—amid a dispute with the European Maritime Safety Agency. The EU regulator almost disallowed Filipino seafarers from working on European flag vessels, claiming that their training and assessment did not meet requirements of the Standards of Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping Convention. The threat put some 50,000 Filipino seafarers in position to become jobless. In April, however, the Philippines committed to improve seafarers’ training and certification, with support from the European Union.

What Future for Migration and Development?

Over the last 50 years, the Philippines has built a comprehensive migration management system that can be described as setting the gold standard for migrant-origin countries. Apart from the robust migration management bureaucracy, the legislature has put in place a policy framework to protect migrants and manage emigration effectively and smoothly. The Philippines is a signatory to five migration-related International Labor Organization conventions (including for domestic workers and seafarers), as well as the 1990 International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families. The Philippines’ approach has been in lockstep with the World Bank, which has called on countries to maximize the development impacts of cross-border human mobility for destination and origin countries as well as migrants themselves.

For individual migrants, financial education continues to be a programmatic mandate to harnessing remittances for savings, investments, and entrepreneurship in the motherland. The pandemic severely affected migrants’ incomes, possibly putting their overall well-being in jeopardy. While leaders in Manila seem eager for more cash remittances, the country has yet to see a massive amount of this money used for investment and entrepreneurship. Remittances invested in real estate may have plateaued. Meanwhile, returnees engaging in domestic entrepreneurial activities during the pandemic may want to emigrate again to continue earning money to send back to their origin communities.

Now, the country faces an inflection point. With the pandemic formally over, the Philippines is not alone among migrant-origin countries seeking to maximize foreign job opportunities for their emigrant workforce in order to rekindle domestic development.

It continues to be a forerunner in migration-related bilateral and multilateral agreements, which can be valuable tools to protect emigrant workers and have already notched some victories. Yet the Middle East still provides challenges, particularly countries with rigorous kafala systems that bind workers to their employers, leaving them in sometimes vulnerable status.

For two years after the COVID-19 outbreak, the Philippines confronted massive return migration. How quickly the country returns to the pre-pandemic level of 2 million deployed OFWs remains to be seen, and will largely be a function of host countries’ labor market needs and restrictions. Recent evidence suggests many countries are racing to attract foreign labor.

Like his father before him, Marcos Jr. is expected to keep emigration a cornerstone of the Philippine economy. Five decades since the 1974 Labor Code, overseas migration has become a demographic phenomenon that some say has revolutionized the Philippines. Emigration, remittances, and the human capital acquired to achieve overseas postings and gained abroad have transformed OFWs and their families into a new middle class that has shaped Philippine society, economy, and culture.

There has been criticism that the labor export policy has led to underinvestment in domestic industry and agriculture. In response, Ople wrote in May 2023, “Our workers choose to work where they wish, aligned with dreams that they have every right to possess.” As the Philippines’ migration management structure reaches the 50-year mark in 2024, it has already overcome the grave challenge imposed by the sudden global halt to mobility. Now, the country must reflect on ways to continue protecting and empowering emigrants over the long haul.

Sources

Aguilar, Filomeno V. 2014. Migration Revolution: Philippine Nationhood and Class Relations in a Globalized Age. Quezon City, Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Ang, Alvin P., Marie Carroline T. Magante, Maria Isabella V. Militante, and Jeremaiah M. Opiniano. 2023. Post-Pandemic Reintegration Efforts for Overseas Filipino Workers: What Prospects Abound? Potsdam: Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom. Available online.

Ang, Alvin and Jeremaiah M. Opiniano. 2022. Seeking for and Returning to Overseas Work? Developments Surrounding Filipinos' Return to Overseas Jobs Beside a Pandemic. In Migranti, Covid, Mercato del Lavoro, eds. Lorenzo Prencipe and Matteo Sanfilippo. Rome: Centro Studi Emigrazione Roma and Scalabrini International Migration Network in Europe-Africa Region. Available online.

Ang, Alvin and Erwin R. Tiongson. 2023. Philippine Migration Journey: Processes and Programs in the Migration Life Cycle. Background paper for the 2023 World Development Report, World Bank, Washington, DC, April 2023. Available online.

Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas. 2023. Personal Remittances Reach a New Record High in December 2022; Full-Year Level of US$36.1 Billion Highest to Date. Press release, February 15, 2023. Available online.

Depasupil, William B. 2023. PH-Kuwait Talks Over OFW Visas Deadlocked. The Manila Times, March 18, 2023. Available online.

Garabiles, Melissa R. and Maruja MB Asis. 2022. Remigration or Reintegration: What Explains the Intentions of Overseas Filipino Workers? Makati, Philippines: International Organization for Migration and Scalabrini Migration Center. Available online.

GMA News Online. 2022. Gov’t Spent P23.05B for Repatriation of 1.7M OFWs during COVID-19 Pandemic – OWWA’s Ignacio. GMA News Online, March 18, 2022. Available online.

Government of the Philippines. 2023. Third Periodic Report Submitted by the Philippines Under Article 73 of the Convention Pursuant to the Simplified Reporting Procedure, Due in 2019. Geneva: Committee on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families. Available online.

Kuwait Times. 2023. Labor Force Hits 2m, Domestic Helpers 25% of Expat Workers. Kuwait Times, April 1, 2023. Available online.

Medenilla, Samuel P. and Recto Mercene. 2020. Recruitment Agencies Shutter Operations Due to Pandemic. BusinessMirror, December 28, 2020. Available online.

Migrant Forum in Asia. 2021. Crying Out for Justice: Wage Theft against Migrant Workers during COVID-19. Quezon City, Philippines: Migrant Forum in Asia. Available online.

Naval, Gerard. 2022. Pinoys Lured to Work as Scammers in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar – DMW. Malaya Business Insight, November 29, 2022. Available online.

Opiniano, Jeremaiah M. 2021. Mysteries Shroud Higher Migra-Dollars to Major Remittance Receiving Countries. BusinessMirror, March 11, 2021. Available online.

---. 2021. Pandemic Prompts PHL Labor-Export Policy Pivot. BusinessMirror, October 7, 2021. Available online.

Opiniano, Jeremaiah M. and C.A. Yap. Forthcoming. A Generation of Crisis-Responsive Reintegration in Migration Management: Reflections from the Philippines. In Return Migration and Crises in Emerging Market Economies, ed. J. Yeo. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

Ople, Susan V. 2023. State of Saudi-Philippine Labor Cooperation Is ‘All Good’. Arab News, May 27, 2023. Available online.

Philippines National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA). 2020. Updated 2017-2022 Philippine Development Plan. Pasig City, Philippines: NEDA. Available online.

---. 2022. Philippine Development Plan 2023-2028. Pasig City, Philippines: NEDA. Available online.

Santos, Rudy. 2023. OFW Deployment Dips Below 1 Million for 3rd Year. The Philippine Star, January 30, 2023. Available online.

Valmonte, Kaycee. 2022. No More Transport, Accommodation Assistance for Returning OFWs in Areas Under Alert Level 1. Philstar Online, May 24, 2022. Available online.

---. 2023. Philippines Commits to Better Training for Seafarers after EU Reprieve. Philstar Online, April 2, 2023. Available online.

World Bank. 2023. 2023 World Development Report: Migrants, Refugees and Societies. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online.