Refugees and Asylees in the United States

For many people in repressive, autocratic, or conflict-embroiled nations, migration is a means of survival. Refugees and asylees seek protection in another country — whether neighboring or distant, familiar or foreign — in order to escape persecution based on their beliefs, personal attributes, or membership in a certain group.

The United States grants humanitarian protection on a limited basis to refugees and asylees from diverse countries throughout the world (see Definitions box) This Spotlight examines the data on persons admitted to the United States as refugees and those granted asylum in 2011. It also provides the number of refugees and asylees who received lawful permanent resident (LPR) status in 2011.

The data come from the 2011 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, the 2011 Annual Flow Report on Refugees and Asylees, and the 2011 Annual Flow Report on U.S. Legal Permanent Residents, published by the Department of Homeland Security's Office of Immigration Statistics (OIS).

Note: All yearly data is for the government's fiscal year (October 1 through September 30).

Click on the bullet points below for more information.

Definitions

- Refugees and asylees are aliens who are unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin or nationality because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution.

- Aliens seeking asylum in the United States can submit an asylum request either affirmatively or defensively.

- Refugees must apply for lawful permanent resident (LPR) status one year after being admitted to the United States.

Refugee Data

- Since 2008, the annual ceiling for the number of refugees admitted to the United States has remained at 80,000.

- Over 56,000 refugees arrived in the United States through the resettlement program in 2011.

- Nationals of Burma, Bhutan, and Iraq made up almost three-quarters of refugee arrivals to the United States in 2011.

- In recent years, Burmese have made up the largest share of refugees resettled in the United States.

- Texas and California received the largest numbers of resettled refugees, taking in more than one-fifth of the resettled refugees in the United States in 2011.

- In 2011, more than 40 percent of refugee arrivals were principal applicants.

Asylee Data

- Nearly 25,000 individuals were granted asylum in 2011, reversing a downward trend since 2007.

- More than 40 percent of foreigners who obtained U.S. asylum in 2011 were from China, Venezuela, and Ethiopia.

Adjusting to Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) Status Data

- Over 168,000 refugees and asylees adjusted to LPR status in 2011.

- More than two-thirds of refugee/asylee LPR status adjusters in 2011 were refugees.

|

Definitions

Refugees and asylees are individuals who are unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin or nationality because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution.

Refugees and asylees are eligible for protection in large part based on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a social group, or political opinion.

In the United States, the main difference between refugees and asylees is the location of the person at the time of application. Refugees are generally outside of the United States when they are considered for resettlement, whereas asylum seekers submit their applications while they are physically present in or at a port of entry to the United States.

Concurrently, refugees and asylees also differ in the way they are treated by immigration and refugee law at the time of application and admission (see sidebar).

Aliens seeking asylum in the United States can submit an asylum request either affirmatively or defensively.

An asylum seeker present in the United States may decide to submit an asylum request either with a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) asylum officer voluntarily at a time of their own choosing (affirmative request), or, if apprehended, with an immigration judge as part of a removal hearing (defensive request). During the interview, an asylum officer will determine whether the applicant meets the definition of a refugee.

If the case is denied, an applicant may appeal for additional hearings with the Board of Immigration Appeals or, in some cases, with federal courts.

Aliens may also request asylum at the port of entry (POE) by informing an inspection officer that he or she is fleeing persecution or seeking asylum. The individual is then referred to an asylum officer for a credible fear interview to determine if he or she has a verifiable fear of persecution. If the claim for asylum is verified, the case is referred to an immigration judge and the individual is placed in nonexpedited removal proceedings. If the claim is denied, the individual is subject to removal.

Refugees must apply for lawful permanent resident (LPR) status one year after being admitted to the United States.

By law, refugees are required to apply for LPR status after an aggregate period of one year of physical presence in the United States. Asylees become eligible to adjust to LPR status also after one year of physical residence in the country. As lawful permanent residents, refugees and asylees have the right to own property, attend public schools, join certain branches of the U.S. Armed Forces, travel internationally without a visa, and, if certain requirements are met, apply for U.S. citizenship.

Until 2005, there was an annual limit of 10,000 on the number of asylees authorized to adjust to LPR status. The implementation of the REAL ID Act eliminated that cap. No annual limit has since existed on the number of refugees eligible to adjust to LPR status.

Refugee Data

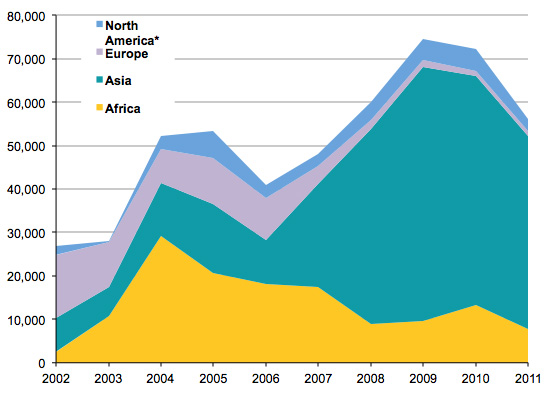

Since 2008, the annual ceiling for the number of refugees admitted to the United States has remained at 80,000.

The number of persons who may be admitted to the United States as refugees each year is established by the president in consultation with Congress. At the beginning of each fiscal year, the president sets the number of refugees to be accepted from five global regions, as well as an “unallocated reserve” if a country goes to war or more refugees need to be admitted regionally. In the case of an unforeseen emergency, the total and regional allocations may be adjusted.

The last time the admission ceiling for refugees was revised was in 2008 when it was set at 80,000, increasing from the ceiling of 70,000 established in 2002 and maintained through 2007. The ceiling was raised by 10,000 in response to an expected increase in refugee resettlement from Iraq, Iran, and Bhutan. However, the current ceiling is 65 percent lower than the 1980 ceiling of 231,700 (see Figure 1).

The 80,000 worldwide ceiling for 2011 is further broken down into regional caps: 15,000 from Africa (down by 500 compared to 2010); 19,000 from East Asia (up by 1,000); 2,000 from Europe and Central Asia (down by 500); 5,500 from Latin America and the Caribbean (no change from 2010); and 35,500 from Near East and South Asia (down by 2,500); 3,000 were unallocated reserve (compared to 500 in 2010 and zero in 2009).

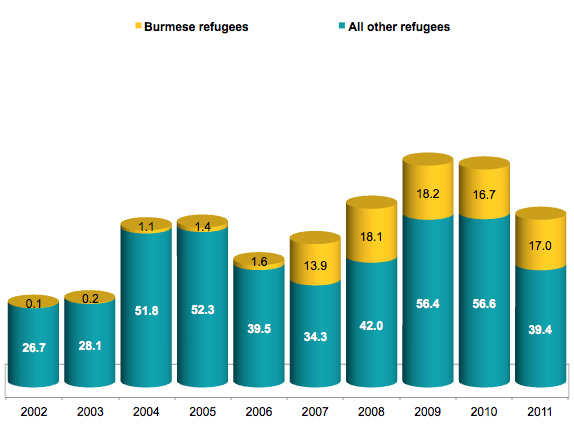

Over 56,000 refugees arrived in the United States through the resettlement program in 2011.

In 2011, 56,384 individuals arrived in the United States as refugees. This declined 23 percent from the number of refugees who resettled in 2010 (73,293) and 24 percent from the 2009 total (74,602), but just 6 percent from the 2008 total when 60,107 refugees resettled in the country (see Figure 2).

|

|

||

|

Nationals of Burma, Bhutan, and Iraq made up almost three-quarters of refugee arrivals to the United States in 2011.

Nationals of Burma, Bhutan, and Iraq represented 73 percent of refugee resettlements in 2011, with 41,359 individuals admitted (see Table 1). In addition to these top three, the top ten countries of origin for refugee resettlements in 2011 included Somalia, Cuba, Eritrea, Iran, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, and Afghanistan. Altogether, nationals of these ten countries totaled 53,469 individuals, or almost 95 percent of all refugee arrivals in 2011.

While the top three countries of origin for refugee arrivals (Burma, Bhutan, and Iraq) have remained the same since 2009, and the overall number of arrivals from these countries has stayed relatively constant, there have been some changes. Refugees from Burma have ranged from 23 percent of the total in 2010 to 30 percent in 2011, those from Bhutan have ranged from 17 percent in 2010 to 27 percent in 2011, and those from Iraq have ranged from 17 percent in 2011 about 25 percent in both 2009 and 2010.

There has also been a significant decline in the number of refugees from Iran, Vietnam, and Burundi since 2009. Persons from Iran accounted for close to 4 percent (or 2,032) of refugee arrivals in 2011, compared to 7 percent (or 5,381) in 2009. From 2002 to 2009, the number of Vietnamese refugees was relatively steady, averaging 5 percent of the total per year, but totaled just 873 (1 percent) in 2010 and 79 (0.1 percent) in 2011. Likewise, refugees from Burundi, whose totals spiked sharply in 2007 (4,545, or 9 percent) and 2008 (2,889, or 5 percent), have rapidly declined to just 110 (0.2 percent of refugees admitted to the United States in 2011). Arrivals from the Democratic Republic of the Congo also spiked sharply in 2010 with 3,174 (4 percent of the total) but fell back to 977 (less than 2 percent) in 2011.

In recent years, Burmese have made up the largest share of refugees resettled in the United States.

In the past decade, Burmese have been the largest group of refugees resettled to the United States with 88,348 (or 17 percent of the total 515,350 refugees) being resettled since 2002. The next two groups are Iraqis (12 percent, or 62,902) and Somalis (11 percent, or 58,050). Though Burmese refugees made up the second largest group in both 2009 and 2010 (after Iraqi nationals), in 2011 Burma was the leading country of origin for refugees resettled in the United States.

|

|

||

|

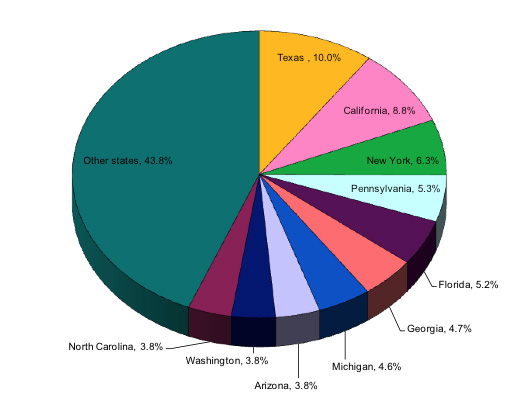

Texas and California received the largest numbers of resettled refugees, taking in more than one-fifth of the resettled refugees in the United States in 2011.

In 2011, the largest shares of refugees arriving in the United States were resettled in Texas (10 percent of all refugees, or 5,627 persons) and California (9 percent, or 4,987). Relatively large shares of refugees were also resettled in New York (6 percent, or 3,529), Pennsylvania (5 percent, or 2,972), Florida (5 percent, or 2,906), and Georgia (close to 5 percent, or 2,636). Over 40 percent of all refugees were resettled in these top six states (see Figure 4).

In 2010, the top six states were California (12 percent, or 8,577), Texas (11 percent, or 7,918), New York (6 percent, or 4,559), Florida (6 percent, or 4,216), Arizona (close to 5 percent, or 3,400), and Georgia (more than 4 percent, or 3,224), together taking in almost 43 percent of the 73,293 refugee arrivals.

|

|

||

|

In 2011, more than 40 percent of refugee arrivals were principal applicants.

In 2011, 44 percent of refugee arrivals, or 25,075 individuals, were principal applicants. As a group, these principal applicants were accompanied by 21,558 dependent children (38 percent of all arrivals) and 9,751 spouses (17 percent of all arrivals).

Asylee Data

Nearly 25,000 individuals were granted asylum in 2011, reversing a downward trend since 2007.

In 2011, 24,988 principal applicants and their spouses and/or unmarried children under the age of 21 were granted asylum. This represents a 19 percent increase versus 21,056 in 2010 bringing the numbers of granted asylum close to the 2007 level (25,211).

Of all the individuals granted asylum in 2011, 54 percent (13,484) were granted asylum affirmatively, while 46 percent (11,504) were granted asylum defensively.

An additional 9,550 individuals outside of the United States were approved for asylum status as immediate family members of principal applicants. Note that this number reflects travel documents issued to these family members, not their arrival to the United States.

More than 40 percent of foreigners who obtained U.S. asylum in 2011 were from China, Venezuela, and Ethiopia.

Asylees from the top three countries of origin for asylum seekers — China, Venezuela, and Ethiopia — made up 43 percent (or 10,784) of all asylees in 2011 (see Table 2). At the same time, the number of Colombian asylees, the second largest group of asylees in 2008 and fourth largest in 2009, has declined significantly from 1,660 in 2008 to 538 in 2011.

More specifically, 8,601 persons from China received asylum in 2011, accounting for 34 percent of all individuals who received asylum that year. The next four largest origin groups were from Venezuela (1,107), Ethiopia (1,076), Egypt (1,028), and Haiti (878), accounting for another 16 percent. Together, nationals of these five countries made up more than half of all individuals who received asylum status in 2011.

Adjusting to Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) Status

Over 168,000 refugees and asylees adjusted to LPR status in 2011.

In 2011, 168,460 refugees and asylees adjusted their status to obtain lawful permanent residence, a 24 percent increase from 2010 (136,291) and a 22 percent decline compared to 2006 (216,454), the highest point since 1995 (see Figure 5).

More than two-thirds of refugee/asylee LPR status adjusters in 2011 were refugees.

Of the 168,460 refugees and asylees who adjusted their status to LPR in 2011, 67 percent (or 113,045) were refugees and 33 percent (or 55,415) were asylees.

Sources

Department of Homeland Security. 2011. 2011 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, Refugees and Asylees Tables. Available Online.

Department of Homeland Security. 2011. 2011 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Legal Permanent Residents Tables. Available Online.

Office of Refugee Resettlement. Available Online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2012. Country Profile: Myanmar (Burma). Available Online.

Further MPI resources

Kerwin, Donald. 2011. The Faltering U.S. Refugee Protection System: Legal and Policy Responses to Refugees, Asylum Seekers, and Others in Need of Protection. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Insitute. Available Online.

Podcast of a Migration Policy Institute event. 2012. Unaccompanied Minors and Their Journey through the U.S. Immigration System. Available Online.

Podcast of a Migration Policy Institute event. 2012. How UNHCR Is Facing a World of New Protection Challenges. Available Online.

Podcast of a Migration Policy Institute event. 2011. Situation of Colombian Refugees in Panama and Ecuador. Available Online.

Podcast of a Migration Policy Institute event. 2010. MPI Leadership Visions: United Nations Deputy High Commissioner for Refugees with T. Alexander Aleinikoff. Available Online.

Podcast of a Migration Policy Institute event. 2010. Potential Reforms to the U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program. Available Online.