You are here

A Fragile Situation: Will the Syrian Refugee Swell Push Lebanon Over the Edge?

Syrian refugees in the Beqaa Valley, Lebanon. (Photo: Pekka Tiainen/EU ECHO)

Approximately 1 million Syrians have sought protection in neighboring Lebanon since the start of a brutal civil war that has displaced millions of Syrians across the Middle East, Europe, and beyond. In Lebanon, where refugees now represent one-fourth of the population, these influxes exacerbate pre-existing tensions in a country already struggling with a weak economy and a complex domestic and regional political situation. Interestingly, the tensions are not just with the native population, but in some cases are even more pronounced with Palestinian refugee communities in Lebanon that have been institutionally discriminated against for decades.

These long-established Palestinian refugees, who suffer from legal and civil barriers to integration and lack of resources in camps where some have lived for decades, have watched as the new arrivals, including about 50,000 Palestinians from Syria, have entered and are viewed as competing for scarce resources and jobs. After years of a “policy of no policy” towards the Syrian arrivals, Lebanese national and municipal governments have recently sought to restrict the movement of newcomers, including by imposing municipal curfews. And notably, the Lebanese government is focusing on returns, with more than 25,000 Syrians being repatriated to Syria, while thousands more are threatened with the same fate.

This article examines the context for Syrian and Palestinian refugees in a country in which political, economic, and social tensions have existed for decades within the native Lebanese population as well as longstanding refugee communities that exist at the margins of society. Coupled with the lack of integration and resources, these tensions suggest that newly arrived Syrians will face increased hardship, with possible effects on the future mobility and well-being of overall refugee communities in Lebanon.

A Fragile Balance

An estimated 300,000 Palestinian refugees and nearly 10,000 others who sought protection (mainly from Iraq) lived in Lebanon prior to the onset of the Syrian civil war in 2011. With the waves of Syrian arrivals, Lebanon now has more refugees per capita than any other country in the world. This influx of refugees (Lebanon officially refers to them as “displaced persons” and generally does not accord them rights beyond those of other foreigners) has put a definite strain on the Lebanese economy. However, Lebanon was already facing multiple economic contractions before the start of the Syrian refugee crisis.

Lebanon’s significant youth unemployment, entrenched informal economy, high inflation and debt obligations, and low GDP—all factors that predate Syrian arrivals—have slowly destabilized its society.

Currently, 28 percent of the local Lebanese population lives below the poverty line, meaning that nearly 1.5 million native-born residents were vulnerable even before the sizeable uptick in arrivals brought new economic and labor market pressures. This poverty falls along geographic lines. For example, the North region of Lebanon has the lowest per capita expenditure and highest level of inequality. This is due to the aftermath of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-90), which saw most rebuilding efforts concentrated in the capital of Beirut, leading to wealth disparities in the rural northern regions and making them the poorest in the country. These same regions have also experienced the majority of Syrian resettlement due to their proximity to the Syrian border; more than 60 percent of Syrians have resettled in the North and Beqaa Valley.

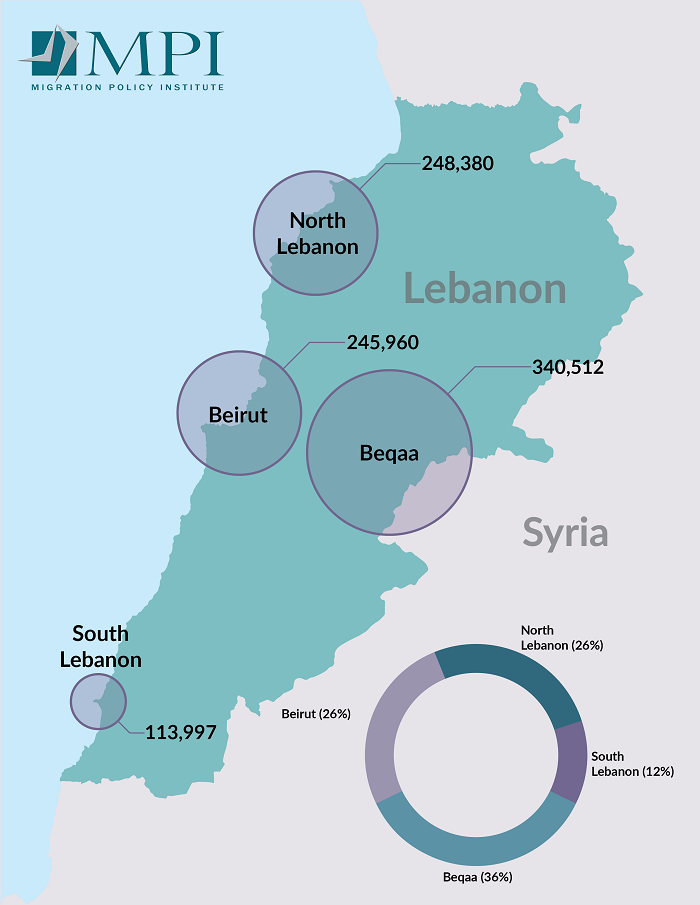

Figure 1. Registered Syrian Refugees in Lebanon by Location

Source: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “Operations Portal Refugee Situations—Syria Situation,” updated December 31, 2018, available online.

Other than the exacerbation of poverty along geographic lines, a number of socioeconomic trends have been made worse by the neighboring civil war. Lebanon witnessed an 8.3 percent drop in its GDP between 2012 and 2015, translating to about US$726 million in reduced annual economic output. Lebanon’s public debt has skyrocketed to become one of the highest in the world, totaling almost US$70 billion, while public spending and borrowing costs continue to accumulate.

Stepping into a Volatile Situation

Beyond the difficult economic and labor market realities, the Syrian arrivals have come amidst a remarkably complex set of political, demographic, religious, foreign policy, and social tensions. Lebanon’s labor force suffers from a lack of work contracts, social safety nets, and inconsistent wages and worker schedules. Due to Lebanon’s initially porous border and lack of migration policies, the first waves of Syrians were able to migrate and work in seasonal and rarely regulated sectors such as agriculture, services, and construction. These were mainly low-skilled workers and, due to the lack of legal oversight, they earned on average more than one-third less than the minimum wage, setting the conditions for greater exploitation.

Many native Lebanese, therefore, have felt threatened by the growing refugee population and the competition they pose to unskilled labor. The 2018 Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon report (VASyR2018), undertaken by three UN agencies, found that competition for jobs was cited as the top factor for tensions with the host community. Thirty-eight percent of Syrian households surveyed cited jobs as the top factor, followed by competition over resources (11 percent) and services (9 percent), and cultural differences (6 percent).

Fear of sectarian imbalance is also on the rise. Most of the Syrians are Sunni Muslims, a reality that could threaten an already segmented Lebanon, in which the existing population is about 45 percent Christian and 51 percent Muslim (divided almost evenly between Shia and Sunni). Lebanon’s modern history has been marred by sectarian violence and today’s system of government (the confessional system, in which the highest offices are reserved for representatives of particular religious communities) rests on a fragile demographic balance. Furthermore, it is important to note the long and contentious history between Lebanon and Syria. During the Lebanese civil war, the Syrian army—at first invited to intervene in the conflict—occupied the country, withdrawing only in 2006. Most recently, Lebanese military forces clashed with Al-Nusra Syrian forces in the Lebanese town of Arsal in 2014. Demographic change, coupled with tense Lebanese-Syrian relations, may upset the power structure and call old systems into question, which could end in more violence.

Additionally, media and popular culture provide insight into current social anxieties and pre-existing stereotypes of Syrians. For example, a comedy show featured a joke about the Lebanese being the minority in their own country while poking fun at the poor background and big families of Syrian refugees, reflecting real fears of changing demographics and the strain on over-extended social services.

Lebanese religious and nonprofit organizations that have been providing humanitarian aid for Syrian refugees are now expecting to see a surge of Lebanese natives also seeking help; some are beginning to allocate a section in their budgets in preparation, such as the Catholic organization Caritas Lebanon, which now sets aside 30 percent of each project budget for local Lebanese communities. Overall, the increased economic strain, geographic poverty divides, and competition with native Lebanese populations for scarce jobs and resources are made worse by the decreasing ability of the cash-strapped government to help.

Syrian Refugees in Lebanon

Most Syrian refugees have settled in previously impoverished areas of the country and are often subjected to severe economic exploitation—in part a consequence of the fact that most lack official work authorization and legal status. The Lebanese government requires that Syrian refugees pay an annual US$200 fee for residency or, if eligible, apply for a fee waiver; however, just 18 percent of Syrian households report that all members have a legal residency permit. In addition to the cost-prohibitive nature of the residency fee, it is difficult to both file a fee-waiver application and be eligible for one—less than 50 percent of Syrian refugees can benefit from the waiver, according to the VASyR2018 report.

Families rely on informal labor methods to survive and an estimated 180,000 Syrian children are in the labor market rather than school. Overall, fewer than half of the 631,000 school-age refugee children in Lebanon are in formal education, according to Human Rights Watch, in large part because of lack of funding for classrooms and teachers and inaccessibility to schools due to lack of transportation.

The VASyR2018 report found that more than half of Syrian refugees are “unable to meet the survival needs of food, health, and shelter.” Sixty-nine percent live below the poverty line, while 82 percent had borrowed money in the three months prior to the survey, demonstrating a consistent lack of resources for everyday needs.

Amid this picture, international aid has proven essential to keep Syrians afloat. However, in 2018, just 38 percent of the nearly US$2.3 billion in funding the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated was necessary for the Syrian refugees in Lebanon was allocated, leaving a gap of $1.4 billion. At year’s end, urgent appeals were being made to help fill the gap, with UNHCR saying children were going without immunizations and other medical care. Food assistance, health care, and water access were also in jeopardy.

Changing Border Policies

Lebanese border policies have also begun to restrict movement. Up until 2015, Syrian refugees could pass through to Lebanon relatively easily due to open-door policies comanaged by the Lebanese government and UNHCR. Yet as fear of sectarian changes and potential spillover of the civil war into Lebanon increased, so did security measures. In 2014, the government instituted border restrictions to “extreme humanitarian cases” and then applied new residency rules and hefty visa renewal costs the following year. Finally, in 2015, the Lebanese government instructed UNHCR to stop registering Syrian refugees all together.

Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon

Palestinian refugees have been a core part of Lebanese politics and society since the 1948-49 Arab-Israeli War and the ensuing arrivals of those who fled the northern regions of what is now Israel. Considering their existence in Lebanon for 70 years, one could assume that integration of Palestinians into Lebanese society occurred long ago. However, the reality is that Palestinian communities have effectively been kept isolated in refugee camps and legally barred from participating fully in the Lebanese economy and society. They are confined to 12 camps, overcrowded and poorly built, and live in 42 “gatherings,” described as urban ghettos. They face many systemic barriers to property ownership, employment, and travel, relying on the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) for basic services such as education and health care.

UNRWA, which was created in 1949 to provide aid to Palestinians, estimates around 450,000 Palestinian refugees registered with the agency as of 2014, although this number would not account for unregistered, or “non-ID,” Palestinians, estimated to be between 3,000 and 5,000. Other sources have much lower numbers, with UNHCR estimating between 260,000 and 280,000 Palestinians living in Lebanon as of 2017, suggesting that many have left the country. The discrepancy in these estimates underscores the marginalized existence of this population: with no official estimate of how many Palestinians live in Lebanon, it is unlikely that Lebanese officials prioritize their integration.

Figure 2. Palestinian Refugee Camps in Lebanon

Source: UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), “Where We Work: Lebanon,” updated July 1, 2014, available online.

Despite their long years of residence, Palestinians are still treated as foreigners and cannot access the same civil rights awarded to native Lebanese communities, nor are they able to fully access the UN recognized right to return to Israel. Living with limited rights and restricted movement, they are entirely dependent on UNRWA and NGO services, and face “acute socioeconomic deprivation,” according to UNHCR.

Because of these circumstances, Palestinian refugees are generally low-skilled, have low education rates, and mostly occupy informal jobs in commerce and construction. An estimated 85 percent of those in the labor force are in the informal sector, compared to half of their Lebanese counterparts. Because of the informal employment, high unemployment, and limited rights, Palestinian communities are therefore more vulnerable and have increased rates of exploitation. The Syrian crisis introduced new arrivals willing to work for less and tolerate more exploitative conditions, exacerbating difficulties for existing communities of Palestinians. Unemployment among Palestinian refugees rose from 8 percent in 2011, when the Syrian civil war began, to 23 percent in 2015.

Palestinians face obstacles within the formal sector as well, since it is difficult to obtain a work permit and they are prohibited from employment in the public sector and 36 other specified professions (such as medicine, law, or engineering). After relying on UNRWA-led primary and secondary education, Palestinians are legally allowed to attend Lebanese universities, but higher education is almost futile considering the lack of employment opportunities following graduation.

The situation of Palestinian refugees may become even bleaker, with UNRWA education and health services under threat. In August 2018, the Trump administration announced it would discontinue funding for UNRWA; the United States had funded about one-third of the agency’s US $1.1 billion budget in 2017. Even though Canada and European Union countries stepped in to partially fill the gap, this development increased concerns over UNRWA dependence by Palestinian communities.

Palestinians from Syria

Around 50,000 of the 1 million Syrian refugees are Palestinians who had originally sought refuge in Syria after the 1948-49 Arab-Israeli War, and their descendants. This often-overlooked demographic will be increasingly important to consider. Palestinians from Syria face the same system of legal and social discrimination and obstacles that earlier-arriving Palestinians have faced for decades. Additionally, many of these newcomers are funneled into existing Palestinian refugee camps, meaning they are physically isolated and constrained, while also dependent on the same limited humanitarian resources on which Palestinians depend. Overall, the integration needs of Palestinian-Syrian refugees connote more competition for the same resources that Palestinian camps are already lacking, potentially leading to more camp-based violence.

Palestinian-Syrians are an extremely vulnerable community as their lack of legal status can lead to fines and deportation (as is also happening to Syrians currently); they also have lost many of the civil rights they had in Syria. While other refugees can integrate physically in different parts of Lebanon and have access to other sources of humanitarian aid, Palestinian-Syrians must solely rely on aid from UNRWA. As a result, 90 percent of new Palestinians from Syria live below the poverty line, compared to 68 percent of pre-existing Palestinians. Additionally, 6 percent of Palestinian refugees from Syria live in extreme poverty.

A series of prohibitive laws from 2013-14 specifically targeted Palestinians from Syria and made entry visa requirements extremely hard to fulfill, pushing many to undertake illegal border crossings. In 2013, Lebanon allowed Palestinian refugees to obtain residency permits valid for three months, renewable at no cost for 12 months. However, after this period, the process to renew the visa and legal residency is relatively expensive. Even though only 3 percent of Palestinians cross illegally, nearly 50 percent lacked a valid visa in 2014. Refugees with and without documents face housing insecurity, increased chances of students dropping out of UNRWA schools and joining internal militias, and factional security threats within the established Palestinian refugee camps.

It is important to specify the most vulnerable populations within these different refugee groups. Of all Syrian arrivals, including Palestinians, 78 percent are women and children. Palestinians from Syria and Syrian students face difficulties in schools since most class instruction in Syria was held in Arabic, while UNRWA and Lebanese schools teach mathematics and science in English or French. Additionally, many Palestinian students may be considered illegal and do not have access to UNRWA services due to difficulties with visa renewals.

Overall, Palestinians from Syria join an already disenfranchised group of Palestinians with a lack of legal rights and opportunities for integration that Syrian refugees technically have.

The Future of Migration Policy in Lebanon

As the situation for refugees deteriorates and simultaneously worsens the pre-existing systemic issues pervading Lebanese governance and society, integration is vital. The most effective way to tackle the Syrian refugee crisis would be for regional cooperation to prioritize development for refugee communities, and not just rely on international aid. However, Lebanon’s government and public often share the mentality that more state spending on development and integration will incentivize refugees to stay. Therefore, increased integration efforts signify the permanence of refugee communities and are perceived as a waste of money, particularly as Lebanon faces economic struggles.

However, ignoring the lack of refugee integration and mobility hurts not just refugee communities but the overall Lebanese society as well. The larger issue is that state capacity barely existed in Lebanon before the Syrian refugee crisis. As a result, there is a need for overall capacity building and social services for all underserved communities, Lebanese and refugee alike. This calls for major collaboration between the Lebanese government and international institutions such as the World Bank, European Union, UNHCR, and UNRWA.

The sectarian, factional issues that have plagued Lebanese and Palestinian communities alike for decades must be addressed for the health of the overall society. Until the systemic barriers facing refugees, whether long-established or recently arrived, are dismantled, the inequality, lack of opportunity, and informal employment will have effects not just on their communities, but for the native Lebanese population as well.

Sources

Abi Raad, Doreen. 2018. Lebanon Overwhelmed with Lingering Syrian Refugee Crisis. National Catholic Register. January 30, 2018. Available online.

Ajluni, Salem and Mary Kawar. 2015. Towards Decent Work in Lebanon: Issues and Challenges in Light of the Syrian Refugee Crisis. Beirut: International Labor Organization (ILO) Regional Office for Arab States. Available online.

Anera. 2013. Palestinian Refugees from Syria in Lebanon. Beirut: Anera. Available online.

Bassam, Laila. 2018. Fifty Thousand Syrians Returned to Syria from Lebanon This Year: Official. Reuters, September 25, 2018. Available online.

Charles, Lorraine. 2017. Lebanon Livelihoods: Economic Opportunities and Challenges for Palestinians and Lebanese in the Shadow of the Syrian Crisis. Sharq.Org. Available online.

---. 2018. Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon: The Neglected Crisis. Forced Migration Forum. Available online.

Charles, Lorraine and Kate Denman. 2013. Syrian and Palestinian Syrian Refugees in Lebanon: The Plight of Women and Children. Journal of International Women’s Studies 14 (5): 96-111. Available online.

Dahi, Omar. 2014. The Refugee Crisis in Lebanon and Jordan: The Need for Economic Development Spending. Forced Migration Review 47: 11-13. Available online.

De Bel-Air, Françoise. 2017. Migration Profile: Lebanon. Policy Brief Issue 2017, No. 12, Migration Policy Centre and Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies at European University Institute, Florence, Italy, May 2017. Available online.

El-Khatib, Ziad, Birger C. Forsberg, David Scales, and Jo Vearey. 2013. Syrian Refugees, between Rocky Crisis in Syria and Hard Inaccessibility to Healthcare Services in Lebanon and Jordan. Conflict and Health 7(18). Available online.

Human Rights Watch. 2018. Lebanon: Mass Evictions of Syrian Refugees. Human Rights Watch, April 20, 2018. Available online.

Ibáñez Prieto, Ana V. 2018. UNHCR Appeals for Emergency Funding for Syrian Refugees. The Jordan Times, September 16, 2018. Available online.

Khoury, Lisa. 2017. Special Report: 180,000 Young Syrian Refugees Are Being Forced into Child Labor in Lebanon. Vox, July 26, 2017. Available online.

Soz, Jiwan. 2018. The Future of the Syrian Refugee Crisis in Lebanon. The Washington Institute. Blog post, July 13, 2018. Available online.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2016. The Situation of Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon. Geneva: UNHCR. Available online.

---. 2018. Survey finds Syrian Refugees in Lebanon Became Poorer, More Vulnerable in 2017. Briefing note, January 9, 2018. Available online.

---. N.d. Operations Portal Refugee Situations—Syria Situation. Last updated December 31, 2018. Available online.

UNHCR, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and World Food Program (WFP). 2018. Vulnerability Assessment of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon. Geneva: UNHCR, UNICEF, and WFP. Available online.

United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). 2014. Where We Work, Lebanon. Updated July 1, 2014. Available online.