You are here

South Asia’s Tibetan Refugee Community Is Shrinking, Imperiling Its Long-Term Future

A temple in Dharamsala, India. (Photo: iStock.com/rchphoto)

The Tibetan refugee community in India, led by the Dalai Lama and his Dharamsala-based exile government for more than six decades, has long served as a model of success for displaced groups worldwide. Rendered stateless in 1959 after being displaced from their Himalayan homeland following the Chinese invasion, the exiles set up a democratic government on foreign soil, comprising a parliament to represent the aspirational constituency in Tibet, an executive branch to administer the daily affairs of its practical constituency in exile, and a supreme justice commission for settling the occasional civil dispute. Over time, the exile government, known as the Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), developed a panoply of cultural, educational, health, and religious institutions serving tens of thousands of refugees in the Indian subcontinent.

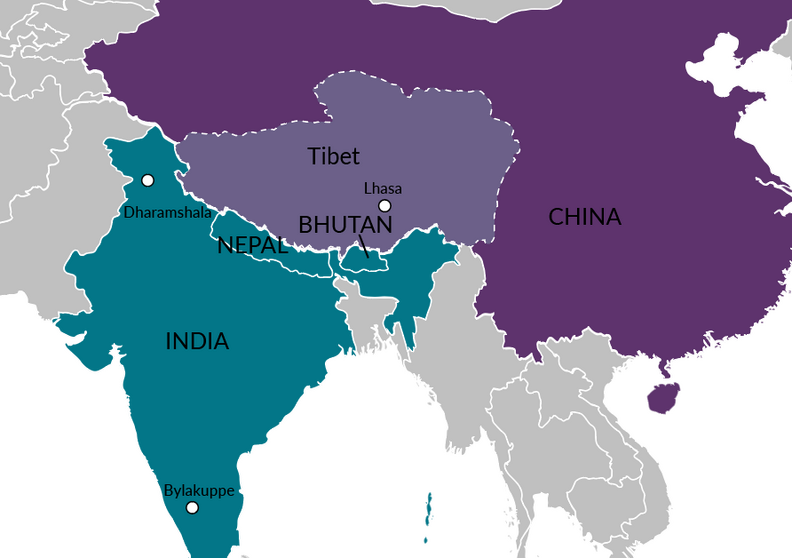

In recent years, however, this hitherto vibrant community has been undermined by steady demographic decline. The number of Tibetan refugees in India, Nepal, and Bhutan has shrunk over the last two decades, from a peak of roughly 150,000 in the 1990s to just above 100,000 today. Precise country-level data are not available, but the vast majority of refugees are in India, with approximately 10,000 in Nepal and 1,300 in Bhutan. This drastic decline has led to the hollowing out of important institutions, including schools, monasteries, and settlements. If demography is destiny, this does not bode well for the future viability and legitimacy of the Tibetan exile government and its institutions.

As this article explores, there are at least three main factors driving this demographic decline: China’s tightening of Tibet’s southwestern borders in the mid-2000s to stem the flow of Tibetan refugees into Nepal and India, the emigration of Tibetan refugees from the Indian subcontinent to the West beginning in the 1990s, and a general decline in the birth rates of exiled Tibetans. These trends are all the more important given the advancing age of the Dalai Lama, who will turn 89 this year. While the octogenarian Tibetan leader devolved his political power to a democratically elected prime minister in 2011, his moral authority and personal charisma—which have kept Tibetan exiles united and protected from the vulnerabilities that commonly affect displaced communities—will be difficult to pass on. If history is any indication, his death will leave a larger-than-life leadership vacuum in the Tibetan diaspora community, especially in India, where the implications of his absence will be most profoundly felt.

Figure 1. Map of Tibet and Region

Note: Map includes China’s Tibet Autonomous Region as well as historical areas comprising the Tibetan homeland.

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) artist rendering.

Soon after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came to power in 1949, China invaded Tibet and forced on the Lhasa-based government the 17-Point Agreement that annexed Tibet into the People’s Republic of China. Hundreds of thousands of Tibetans were killed during the invasion and the subsequent brutality of the occupation, prompting the young Dalai Lama to flee into exile in 1959. More than 80,000 Tibetans followed him into India, a natural destination because of its spiritual ties and geographical proximity. On April 29, 1959, the Dalai Lama established a Tibetan government-in-exile, with the twin objectives of assisting the refugees and restoring freedom in Tibet. Initially headquartered in the northern Indian hill station of Mussoorie, the CTA relocated to its current seat in Dharamsala, in the state of Himachal Pradesh, in 1960.

With the goal of physical survival in the moment and Tibetan cultural preservation in the long run, the Dalai Lama sought the Indian government’s help in creating rehabilitation programs for Tibetan refugees in agriculture-based settlements across India, leveraging the agricultural expertise prevalent among the early exiles. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru urged various state governments to allocate land for the refugees, and the government of southwestern Mysore (now Karnataka) allocated more than 3,200 acres of forest land to the Tibetans, leading to the establishment of the inaugural Tibetan exile settlement in 1961 in Bylakuppe, known as Lugsam Samdupling. There were numerous adversities along the way, including scarcity of water and food, as well as vast swaths of jungle that the refugees needed to convert into arable land with little modern equipment. Now, the state of Karnataka is home to the largest number of Tibetan refugees in India (approximately 21,300 as of 2023, according to the Indian government), followed by Himachal Pradesh (15,000).

The first decade of exile was marked by death and disease, particularly of children, due to overcrowding, malnutrition, unsanitary conditions, and the sudden change of climate. Eventually, refugees built 46 economically self-sufficient settlements, most of which are agriculture-based while some are handicraft and industry-based. They established nurseries, schools, hospitals, monasteries, and cultural centers. Over time, the Tibetan exile community became a model of success for other displaced groups around the world. Scholars, researchers, and other observers have long been intrigued by the setup of the Tibetan government-in-exile and its robustness.

Charting the Demographic Decline

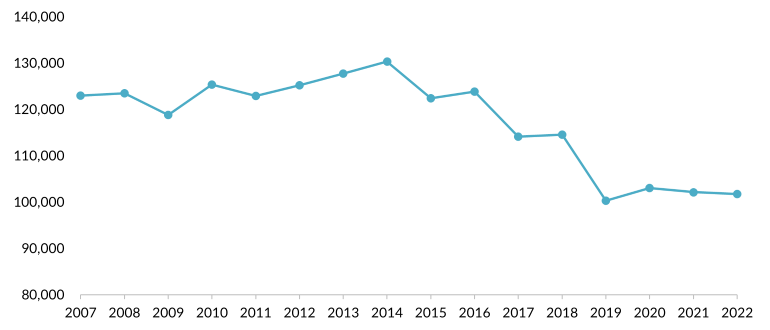

Over the last two decades, Tibetan communities in the Indian subcontinent have witnessed a persistent demographic decline, posing a significant threat to their long-term survival. Though this change is difficult to measure because of the transient nature of refugee life, data from the CTA obtained by the authors show a 17 percent decline in population since 2007, from approximately 123,000 to 102,000 in 2022 (see Figure 2). The decline has been especially pronounced since 2014.

Figure 2. Exile Tibetan Population in Bhutan, India, and Nepal, 2006-22

Note: A change in methodology between 2018 and 2019 excluded the monastic population from the count. The authors attempted to account for this by incorporating approximately 25,000 monastics into settlements with the highest concentration of clergy, based on estimates for the number of Tibetans in regional monasteries and nunneries.

Source: Data obtained by the authors from the Central Tibetan Administration’s (CTA) Department of Home.

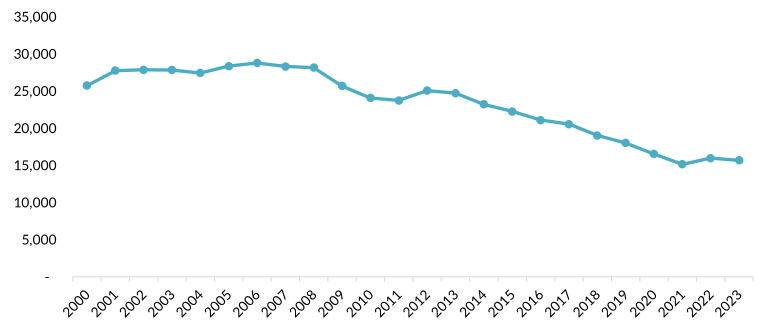

Another sign of the population drop is the substantial downturn in the number of students enrolled in CTA-affiliated refugee schools in India and Nepal, especially since 2008 (see Figure 3). From 2000 to 2023, enrollment fell by 39 percent, from approximately 25,700 to 15,700. If this rate of decline were to continue, the student population would drop below 10,000 by 2043. Because of the diminishing number of Tibetan students, several schools in settlements in India have been closed. From 2016 to 2023, the number of schools directly or indirectly affiliated with the CTA contracted from 71 to 66.

Figure 3. Students Enrolled in Tibetan Refugee Schools in India and Nepal, 2000-23

Source: Data obtained by the authors from the CTA’s Department of Home.

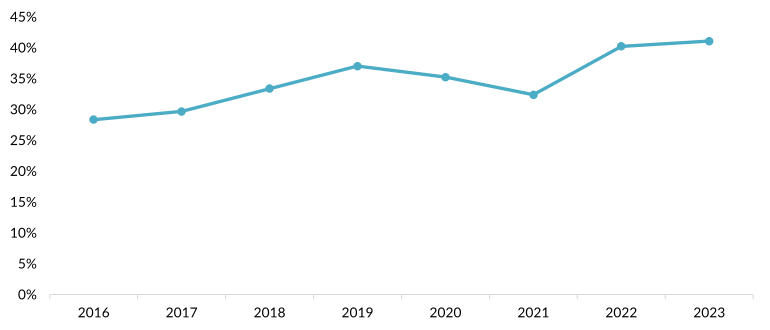

To stabilize the student population, educational institutions have begun admitting thousands of non-Tibetans from Himalayan communities that share the Tibetan Buddhist cultural heritage. This policy has helped stall the rapid decline in the number of students and even reverse it, from 15,200 students in 2021 to 16,000 in 2022. CTA data show a consistent and notable increase in the proportion of non-Tibetan students in these schools, from 28 percent in 2016 to 41 percent in 2023 (see Figure 4). The growing presence of non-Tibetan students compensates for the declining number of Tibetan students and helps stabilize the exile institutions.

Figure 4. Percentage of Non-Tibetan Students in Tibetan Schools in India and Nepal, 2016-22

Source: Data obtained by the authors from the CTA’s Department of Education.

Explaining the Demographic Decline

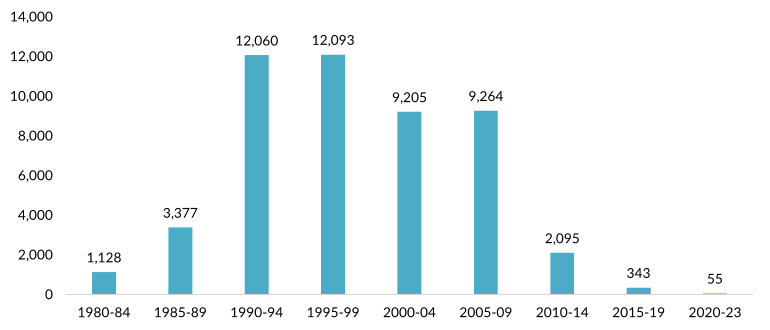

One major contributor to the decline of the exile Tibetan population is a striking decrease in the number of new arrivals from Tibet in the last two decades. The wave of refugees from Tibet to India rose in the 1980s, when the era of reform and opening under China’s leader Deng Xiaoping brought a degree of liberalization to Tibet. This number peaked after 1989, when the awarding of Nobel Peace Prize to the Dalai Lama propelled the Tibet issue into the global limelight. Throughout the 1990s the Tibet-Nepal borders were relatively porous, and an average of 2,300 refugees passed through Nepal to arrive at the refugee reception center in India each year. Many new arrivals were young and were enrolled in the Tibetan Children’s Village, the network of schools for orphans and refugee children previously run by the Dalai Lama’s sister, Jetsun Pema. Those who were too old for secondary schooling often entered Tibetan monastic colleges in South India.

This steady stream of refugees came to a halt in the years just before the 2008 Beijing Olympics. One notorious incident, known as the Nangpa Pass shooting, symbolized China’s growing crackdown on Tibetan escape routes in the Himalayas. In October 2006, Chinese border guards opened fire on a group of 70 Tibetan refugees climbing the snow-covered Nangpa Pass en route to Nepal. Initially, the Chinese government claimed the border guards were acting in self-defense, but a video of the incident filmed by a Romanian mountaineer showed the Tibetans were unarmed and running away. A 17-year-old nun, Kelsang Namtso, died in the snow, while 23-year-old Kunsang Namgyal was hit by two bullets, taken away by the police, and was believed to have died.

For those seeking to escape Tibet, the dangerous pathway became even more perilous in the post-2008 era, when Beijing intensified its mass surveillance programs and placed severe restrictions on Tibetans’ internal mobility. China’s increased controls over Tibetans’ movement within the country and over the Tibet-Nepal border made it all but impossible for Tibetans to reach India. The number of new arrivals dropped to approximately 419 per year in the 2010-14 period (see Figure 5). Restrictions further intensified under President Xi Jinping, who became China’s leader in 2012. In the last four years, just 55 Tibetan refugees arrived in India.

Figure 5. Newly Arrived Tibetan Refugees Registered in India, 1980-2023

Source: Data obtained by the authors from the CTA’s Department of Security.

Migration to the West

A second factor contributing to the community’s demographic decline is the wave of migration to the West sparked by the Immigration Act of 1990, when the United States offered to take in 1,000 displaced Tibetans. The following year, Australia began accepting a quota of Tibetan refugees each year, almost all of them former political prisoners or their family members. Over the next two decades, thousands of Tibetans migrated to the United States, Canada, Australia, France, and other Western nations.

Also, since the 1990s, as the Nepalese government developed closer relations with Beijing, the security of Tibetans in Nepal has been increasingly imperiled. When the Maoist Party came to power in Kathmandu in the 2000s, authorities began restricting Tibetans from engaging in not only political activities but also cultural expressions. Tibetans faced a strict ban on street protests, sharp restrictions on cultural activities such as celebrating the Dalai Lama’s birthday, and alleged frequent abuses at the hands of Nepalese security forces. Nepal has banned Tibetans from participating in exile parliamentary and presidential elections. As a result of these policies, Tibetan refugees left Nepal in droves. Whereas the Tibetan population in Nepal was roughly 20,000 in the mid-1990s, it is now estimated to be half that size, accounting for about one-tenth of Tibetan refugees in South Asia.

Many Tibetan refugees who have gone to Bhutan eventually resettle in India or acquire Bhutanese citizenship. As such, Bhutan is home to the fewest number of Tibetans in the region.

Compared to Nepal, Tibetan refugees in India enjoy greater security and protection, and even a degree of limited self-government in settlements with concentrated refugee populations. Nevertheless, Tibetans in India face restrictions in buying property, getting business licenses, and voting in elections. They also pay higher university fees because of their designation as foreigners. Without Indian citizenship, a privilege that was inaccessible to Tibetan refugees until recently, Tibetans were unable to hold Indian government jobs, own property without approval from the Reserve Bank of India, or legally own companies or buy shares. For Tibetan refugees living a life on the political margins in India and of extreme insecurity in Nepal, new destinations in the West represented a promising pathway to economic security and political citizenship.

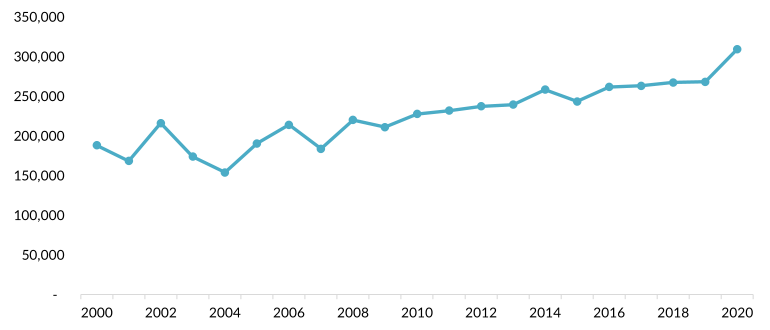

While there is no precise estimate of the size of the Tibetan diaspora in the West, there is evidence that it is substantial and growing, particularly in the United States. Data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) show that approximately 309,000 U.S. residents spoke the Tibetan language at home as of 2020, a 64 percent growth over the 188,000 in 2000 (see Figure 6). Not everyone who speaks Tibetan is a Tibetan national; thousands of Himalayan people—including Nepalese Sherpas and Indian Monpas—are ethnically and linguistically Tibetan but are not Tibetan nationals. Still, this linguistic metric is a useful proxy to show the population's general size and trend.

Figure 6. Tibetan Speakers in the United States, 2000-20

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Surveys.

Fewer Births

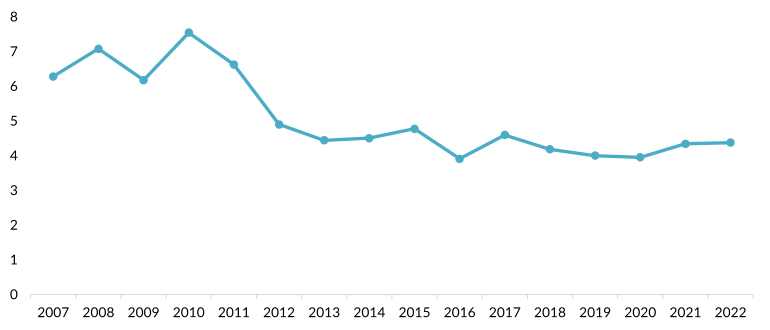

The third major factor contributing to the decline in the exile Tibetan population in the Indian subcontinent is the low birth rate within the community. In 2022, there were approximately 4.4 live births per 1,000 Tibetans in India, Nepal, and Bhutan, down from about 6.3 live births in 2007, according to the authors’ calculations (see Figure 7). This crude birth rate is notably lower than in India as a whole (16.3 in 2022) and China (6.8 in 2022), according to the World Bank.

Figure 7. Birth Rate of Exile Tibetan Community in Bhutan, India, and Nepal, 2006-22

Source: Authors’ calculation based on data from the CTA’s Department of Home.

One reason for this declining birth rate is the high literacy rate among exile Tibetans in the Indian subcontinent. Studies have indicated that a 1 percent increase in female literacy is associated with a decrease in the crude birth rate by 0.33 per 1,000 live births. Thanks to the vast network of CTA-administered schools and related educational institutions, Tibetans in exile have increased their effective literacy rate from about 25 percent in the late 1960s to 82 percent in 2009, and this rate is sure to be even higher now. By comparison, the literacy rate across India was 74 percent in 2022, according to World Bank data. Another factor is the knock-on effect of migration, which tends to separate families and typically shortens a woman’s child-bearing window. Other social factors such as changing marriage customs and nuclearization of the Tibetan family may also help explain the lower birth rate.

The demographic decline of South Asia’s Tibetan community poses a threat to the future viability of the government-in-exile—the sole democratic voice representing the Tibetan people both inside and outside Tibet—as well as its institutions and civil-society organizations. If this trend continues, it could imperil the Tibetan monastic universities in South India dedicated to safeguarding Indo-Tibetan knowledge systems as well as hundreds of health and education facilities serving tens of thousands of Tibetans and others across India.

Interestingly, recent years have seen new developments that might moderate the pressures driving down the size of the Tibetan population in South Asia. In 2014, the Election Commission of India sent the states a directive that Indian-born children of Tibetan refugees were eligible for Indian citizenship if they were born between January 26, 1950 and July 1, 1987. A small but growing number of eligible Tibetans are applying for Indian citizenship and starting to vote in district-level elections, a trend that is helping Tibetan communities build local power and reduce their collective insecurity. Seeking Indian citizenship was once frowned upon among Tibetan exiles, but this taboo is beginning to lift as the experience of Tibetans in the West has demonstrated that it is possible to take up foreign citizenship without compromising one’s Tibetan identity and allegiance to the exile government.

Additionally, a growing number of young Tibetans born in the West are making rite-of-passage trips to India to connect with their cultural and linguistic roots, often through summer camps and other immersion programs. Recognizing the growing demand, Tibetan schools in Dharamsala and monasteries in South India are developing a wide range of summer programs catering to Western-born Tibetans of various age groups and language fluency levels. While in India, these young students can reconnect with their heritage, relearn their language, and sometimes volunteer for the CTA and other Tibetan organizations. This allows them to contribute skills and energy to exile initiatives while gaining an immersive Tibetan experience. These programs have the potential to draw thousands of Tibetan children back to India in the future, strengthening the exile economy and its cultural and social fabric.

While these developments are encouraging, addressing the overall demographic decline and underlying structural challenges is critical to sustaining the vitality of the Tibetan exile community. Despite its demographic challenges and other obstacles, the CTA and the Tibetan refugee community in India remain the diaspora’s moral and political center. The CTA maintains its pivotal role in advocating for the fundamental rights and collective aspirations of the Tibetan people, serving as the political and administrative nucleus of the exile community, including those in the West. At a time when the Tibet issue has faded from the global limelight, and as the diaspora braces for the uncertainties after the passing of this internationally known Dalai Lama, the significance of the role the CTA serves is all the more important.

Sources

Bernstorff, Dagmar and Hubertus Von Welck, eds. 2004. Exile as Challenge: The Tibetan Diaspora. Hyderabad, India: Orient Longman.

Central Tibetan Administration (CTA), Planning Commission. 2010. Tibetan Demographic Survey, 2009. Dharamshala, India: CTA Planning Commission.

CNN. 2010. Nepalese Authorities Confiscate Tibetan Ballot Boxes. CNN, October 5, 2010. Available online.

Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs. 2023. Annual Report 2022-23. New Delhi: Government of India, Ministry of Home Affairs. Available online.

Howe, Marvine. 1991. U.S., in New Step, Will Let In 1,000 Tibetans. The New York Times, August 21, 1991. Available online.

Human Rights Watch. 2014. Nepal: Increased Pressure from China Threatens Tibetans. Press release, Apil 1, 2014. Available online.

Madhukar, Abhishek and Rina Chandran. 2017. Sixty Years After Fleeing Tibet, Refugees in India Get Passports, Not Property. Thomson Reuters Foundation, June 21, 2017. Available online.

Shain, Yossi. 2005. The Frontier of Loyalty: Political Exiles in the Age of the Nation-State. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Tibetan Legal Association. 2022. Legal Overview of the Status of Tibetans in India. May 25, 2022. Available online.

Voice of America. 2015. In Australia, Tibetan Immigrants Learn to Swim. Voice of America, April 16, 2015. Available online.

Von Fürer-Haimendorf, Christoph. 1990. The Renaissance of Tibetan Civilization. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Watts, Jonathan. 2006. Death on Tibetans' Long Walk to Freedom. The Guardian, October 30, 2006. Available online.